Curriculum Development Theory and Strategy

In developing a curriculum, a proper choice of development theory plays a vital part. A correctly identified and meaningful theory presents a core around which all subsequent actions are performed. Importantly, the realities of a modern world present certain challenges for individuals involved in the curricular development. Therefore, some theories are considered ill-fitted for the requirements set up by modern social and cultural setting. For instance, the theories which are collectively known as subject-centered are only partially applicable to the modern school education.

On the other hand, the humanistic theory, currently used in our school district, is commonly criticized for the lack of robustness, giving way to uncontrolled deviations (Rolfe, 2014). Besides, the success of learning process based on the humanistic theory visibly depends on the proficiency of teachers, which puts additional burden on the bodies responsible for hiring and training of staff (Rolfe, 2014). Therefore, the updated curriculum is to be built upon a broader learner-centered theory, with particular emphasis on experience. An experience-centered curriculum has several advantages over the current humanistic-oriented one:

- Offers an opportunity for continuous and dynamic adjustment in the educational process;

- Favors disciplines over subjects, strengthening the position of multidisciplinary learning;

- Improves compatibility of the presented material with the needs and interests of students;

- Allows flexibility of the learning process not only for educators but also for students, which promotes empowerment and initiative;

- Students are exposed to experience-based situations which improve critical thinking and activate their capacity for knowledge applicability;

- Introduce interest points which serve as anchors for actualization of existing formal knowledge;

- Promotes collaboration and social skills (Ornstein & Hunkins, 2013).

Most importantly, since the experience-based theory resides within learner-based domain, it is expected to improve the results of education without disrupting the majority of established school activities. In other words, the current staff is expected to have few difficulties during the transition. Therefore, the curricular strategy of discovery learning, which currently serves as a foundation for our knowledge delivery, can be retained for the new curriculum design. In accordance with this strategy, the observations of the specific objects and processes can be utilized to describe broader concepts and phenomena while at the same time actualize the obtained experience and suggest its applications in other situations, catering to the requirements of the experience-based theory.

Curriculum Cycles and Phases

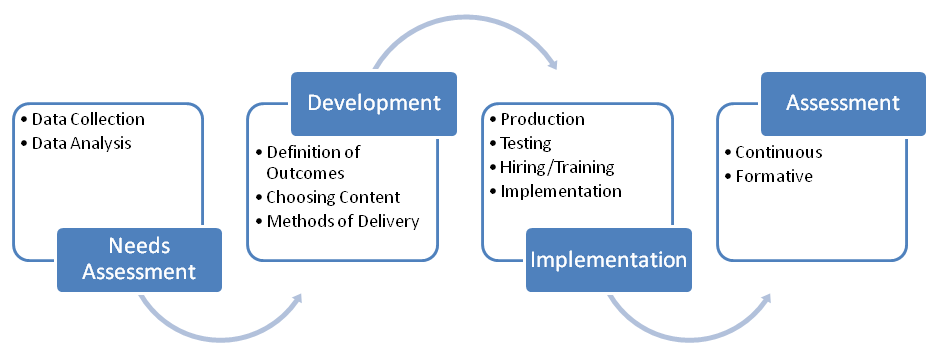

To ensure the systematic and methodical approach to design, the curriculum development is to be developed in four consecutive steps, commonly termed components. The first component is the assessment of needs. During its first phase, the relevant data on the success and shortcomings of the curriculum is collected. This can be done either through review of the available results of student testing, such as achievement tests, or, if the data is insufficient or imprecise, by issuing additional tests to the target groups (English, 2010). During the next phase, the collected data is processed and converted into meaningful results. This phase allows detecting the disadvantages and flaws in the previous design which are to be addressed during the development as well as the benefits and successful decisions which can be retained or adapted to the new curriculum. Importantly, the learner-based curriculum also requires the acknowledgment of behavioral patterns of the students. Therefore, it is also necessary to collect and process the data which illustrates it (Gordon & Browne, 2013).

The second component is the development of curriculum. The first phase of development is based on the pursued philosophy of the establishment and consists of determining the goals and objectives of the learning process. The former illustrate the general desired direction taken by the establishment while the latter are used to specify the concrete outcomes of the process, e.g. the results demonstrated by the students after completing a school year or studying a specific discipline (Ornstein & Hunkins, 2013). During the next phase, the educational content is chosen which creates the best opportunities for reaching the set goals and objectives.

This data obtained during the needs assessment component can be of particular use here since most of the time the success of student outcomes depends can be traced back to the educational content. This is a comparatively voluminous phase since the preferable arrangement of the chosen material is also decided during this phase. Finally, the scope and depth of the content must be determined during this phase to ensure the compatibility of the content with the intended outcomes. On the final phase of this component, the content is supplied with relevant methods of delivery. Two sets of data are expected to be produced at the end of this component, one listing the activities (e.g. methods) aligned with the developed curriculum and another containing details on the intended accommodation of the curriculum. Such approach to development, known as backward design, is a recent innovation thought to be beneficial for certain disciplines (Richards, 2013).

The third component is the curriculum implementation. During the first phase of implementation, the curriculum product is produced. This phase should be allocated enough time and resources to allow for finding a vendor and settling organizational issues. Once this is done, the testing phase commences. First, the committee responsible for the design devises an appropriate set of tests and the criteria for determining their success. Next, the participants (teachers and students) are allocated, and relevant means of monitoring and communication are established.

If the testing produces signs of faulty design or the designated performance criteria are not met, the curriculum is retracted and revised in attempt to amend the mistakes. If the testing is successful, the next phase commences, which ensures the level of qualification required by the new curriculum. These requirements are met by updating the knowledge and skills of the existing staff and modifying the hiring practices to obtain new specialists if necessary. Finally, during the fourth phase of this component, the new curriculum is being implemented in the manner similar to testing with a similar level of monitoring but on a larger scope.

The final component of the curriculum design is evaluation. It consists of two phases similar to those of needs assessment, although they do not follow each other in succession. Rather, the data collection and analysis occur persistently throughout the course of curriculum implementation and form a basis of the data which can later be used during the needs assessment once the need arises to review the curriculum (English, 2010).

Stakeholder Involvement and Conflict Management

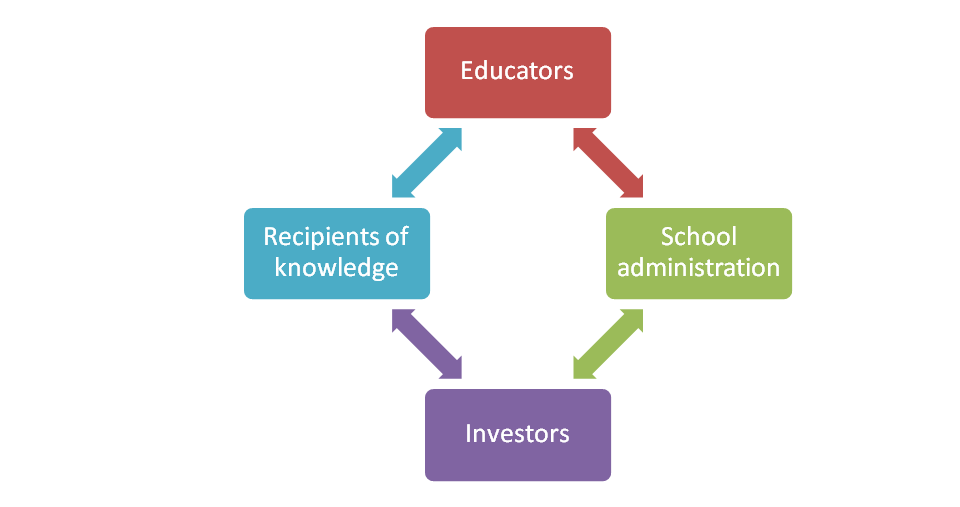

Four primary stakeholder groups can be outlined in the curriculum design. The first consists of educators. The second includes school administration and related managerial groups involved in the process. The third is the entities responsible for investment and supply of resources. The fourth is the recipients of knowledge. Aside from the students, this group includes their parents and the local community. The latter two do not participate directly in the curriculum design but their expectations are important to address. The local community, in particular, is interested in having skilled young generation capable of effectively operating in the modern society (Cullen & Hill, 2013).

Some of its members such as local employers can produce relevant data on shortcomings of education. Therefore, communication channels need to be established to collect the data from this group. One way of doing this is development of a section on a school district website where suggestions can be filed and tracked for the taken actions. Naturally, conflicts of interests are expected to occur, which can be managed through the same system. For instance, if the expectation of parents are not met, the relevant section of the website must feature a detailed explanation of the reason for the decision to decline the suggested innovation and provide rationale for the preferred alternative. In addition, regular meetings of the representatives of each stakeholder group must be scheduled, during which the arising conflicts can be settled and optimal decisions negotiated.

Curriculum Development Timeline

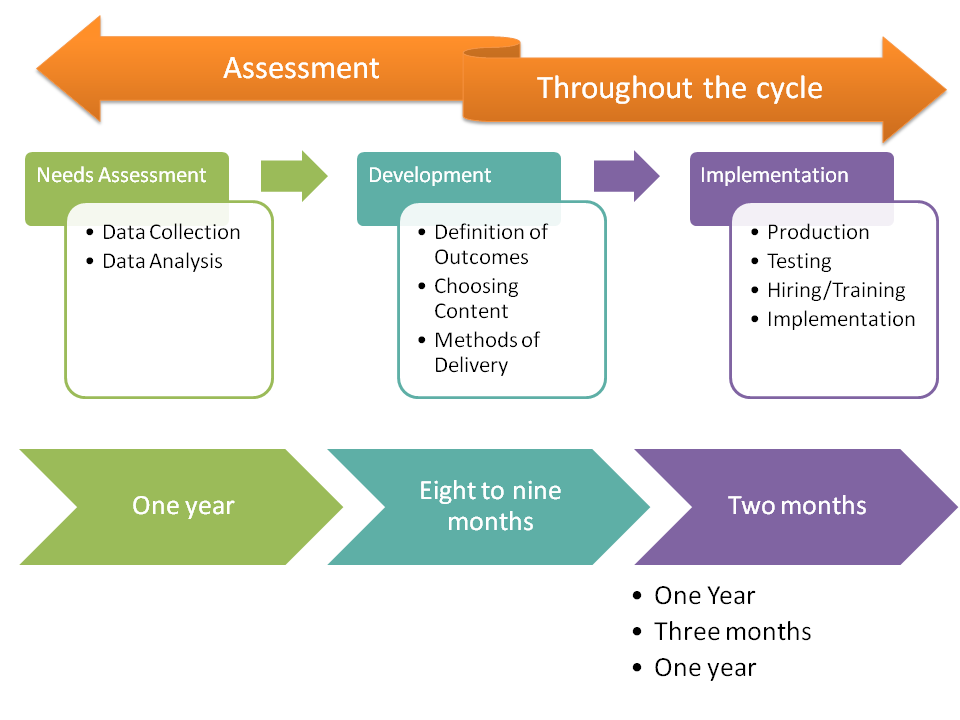

The estimated time for developing a new curriculum is four years from the initial needs assessment to the commencing of the assessment phase. Data collection of the first component requires at least one full year to form a meaningful picture of the strengths and weaknesses of the pervious design. The development component requires a similar amount of time, with the content and methods of delivery being the most time-consuming phases. The choice of goals and objectives is relatively short given the fact that they are largely similar with those characteristic for the humanistic design theory. Unless the data points to the emergence of new demands by the environment, all of the phases, including the preliminary assessment of the design, are to be completed within eight to nine months.

The implementation component is much more lengthy, with the production of the initial artifact requiring the least time (less than two months). However, the testing demands a full year cycle and can commence directly after the artifact is produced. Since its results will produce the data useful for adjusting hiring and training practices, their approximate combined duration is to be around three months total. Finally, the full implementation is expected to occur the next year, making two years the shortest possible duration. Since evaluation (the fourth component) is not bound to a certain period, it is not listed separately but instead commences simultaneously with the full implementation.

Acknowledgment of Current Trends

The recent highly dynamic urban environment sets new requirements for citizens, including the ability to think critically, operate within an unfamiliar setting, and apply existing knowledge to create value (Zahabioun, Yousefy, Yarmohammadian, & Keshtiaray, 2013). Such demands are traditionally associated with problem-centered approach, which gains popularity in modern curricular design (Savery, 2015). However, a learner-centered theory also encourages independent inquiry, promotes lifelong learning, and prepares learners for real-world problems (Savery, 2015). Therefore, the acknowledgment of the recent trends in curricular design is possible without deviation from the chosen theory and strategies.

References

Cullen, R., & Hill, R. R. (2013). Curriculum designed for an equitable pedagogy. Education Sciences, 3(1), 17-29.

English, F. W. (2010). Deciding what to teach and test: Developing, aligning, and leading the curriculum. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2013). Beginnings & beyond: Foundations in early childhood education. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Ornstein, A. C., & Hunkins, F. P. (2013). Curriculum: Foundations, principles, and issues. Harlow, England: Pearson Education, Limited.

Richards, J. C. (2013). Curriculum approaches in language teaching: Forward, central, and backward design. RELC Journal, 44(1), 5-33.

Rolfe, G. (2014). Rethinking reflective education: what would Dewey have done?. Nurse education today, 34(8), 1179-1183.

Savery, J. R. (2015). Overview of problem-based learning: Definitions and distinctions. In A. Walker, H. Leary, C. Hmelo-Silver, & P. Ertmer (Eds.), Essential readings in problem-based learning (pp. 5-15). West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press.

Zahabioun, S., Yousefy, A., Yarmohammadian, M. H., & Keshtiaray, N. (2013). Global citizenship education and its implications for curriculum goals at the age of globalization. International Education Studies, 6(1), 195-206.