Introduction

In his book “I Hate the Internet,” Kobek uncovered the ugly sides of the Web loved and admired by everyone today, especially by the younger generation. As pointed out by the National Crime Prevention Council (NCPC), the teenagers and children growing up in the contemporary world represent an online population (2). This statement particularly means that the youth tends to spend a lot of time online and using their digital devices for various purposes such as education, information, entertainment, and communication. It goes without saying that the rapid development of technologies and the emergence of the World Wide Web has become very beneficial for modern society; however, alongside the advantages offered by this technological breakthrough, there exists a broad range of disadvantages, risks, and harmful impacts facilitated by it. Unfortunately, spending a lot of time on the Internet, modern teenagers become extremely vulnerable to these negative effects. One such effect is cyberbullying. Being a variation of regular bullying and a rather common phenomenon online, cyberbullying tends to have a number of very strong adverse effects on teenagers, facilitating depressions, social isolation, fear, and stress; however, there exist different ways in which cyberbullying can be addressed by parents, law enforcement, and victims.

Cyberbullying as a Phenomenon

Bullying, in its regular forms, is known to be one of the common behaviors among adolescents and teenagers (Hinduja and Patchin 2). Bullying includes the behaviors that are initiated for the purpose of humiliating, hurting, or scaring the individuals at whom they are directed. Bullying can be of both emotional and physical nature. According to the report of the Anti-Defamation League, at least 22% of schools children aged 12 to 18 admit being bullied by their peers (1). The teenagers usually report such forms of regular bullying as mocking and name-calling (13.6% prevalence), gossip and rumors (13.2%), exclusion (4.5%), physical assaults (pushing, tripping, spitting) (6%), threats (3.9%), and the destruction of personal property (1.6%) (Anti-Defamation League 1).

When it comes to the phenomenon of cyberbullying, it is important to note that this term is relatively new and did not exist ten years ago (Notar et al. 1). Cyberbullying is defined as “the intentional and repeated mistreatment of others through the use of technology, such as computers, cell phones, and other electronic devices” (Anti-Defamation League 1). As the contemporary teenagers are a population group that is characterized by very frequent use of digital technologies and the internet on a daily basis, they are just as likely to become victims of cyberbullying as adults using the Internet (National Crime Prevention Council 1-2). In particular, the prevalence of cyberbullying in teenagers is rather high. According to the data of the National Crime Prevention Council, about 43% of teenagers in the United States state that they have become victims of cyberbullying over the past year; this percentage indicates that at least four out of ten teenagers experience bullying annually (2).

Also, the data of the NCPC shows that the prevalence of cyberbullying is not equally high among male and female youths; research found that female teenagers suffer from bullying on the internet more often than their male counterparts (2). The teenagers aged 15 and 16 faces bullying more commonly than the youths of other ages. This tendency may occur due to the development patterns typical for this age such as the advancement intellectual capacity (abstract and critical thinking, judgment); at this age teens develop their own opinions that often clash with or criticize those of other people; also, conflicts and harmful behaviors such fighting, bullying, shaming, substance abuse, and self-harm are powered by the children’s desire to separate themselves from the society, and define themselves as individuals (“Ages 15-18: Developmental Overview”).

The fact that cyberbullying is a phenomenon that occurs in the cyberspace should not serve as a reason to believe that this behavior is not a serious threat to the well-being of teenagers. In fact, cyberbullying is just as harmful as regular bullying. Bullies that operate on the Internet do not need to have physical strength or be fast runners; in addition, they can engage many people in their aggressive activities, or exploit the ubiquity of the internet to access personal information of their victims or target them in many different locations (Notar et al. 1). In cyberspace, teenagers can be attacked with the help of such instruments as photographs, video clips, voice records, rumors, blogging, and postings online (Notar et al. 2). The prevalence of witnessed cyberbullying is reported to be as high as 87% annually (Anti-Defamation League 1-2). The diversity of modes and means used for its accomplishment makes cyberbullying particularly dangerous for its teenage victims; namely, it can surface in such forms as sexual harassment and exploitation of minors, translate to physical assault in real life, or be aimed at the identities and appearances of the victims, thus representing hate crime.

Moreover, this phenomenon is not specific only to the United States but is recognized globally with the incidence rates ranging from 6 to 35% (Bottino et al. 464). Logically, a phenomenon with such serious prevalence and wide reach tends to produce very significant negative impacts on the teenagers, who become its victims. One of the examples of this kind of impact occurred in 2003 – it is the case of Ryan Halligan, a teenager whose cyberbullies led him to believe that they were actually his friends and encouraged the boy to share intimate information with them. As soon as the information was received, the bullies made it public and started a rumor that Ryan was gay; after facing a major and heavy embarrassment in the community of his peers, Ryan ended his own life by hanging himself (“The Top Six Unforgettable CyberBullying Cases Ever”). Ryan’s father made a heartbreaking comment of his son’s death by saying: “technology was being utilized as weapons far more effective and reaching [than] the simple ones we had as kids”(“The Top Six Unforgettable CyberBullying Cases Ever”).

The Effects of Cyberbullying on Teenagers

Bullying can be based on a variety of features and aspects of an individuals’ personality, identity, of appearance. To be more precise, according to the report of Anti-Defamation League, appearance and body size is one of the most common causes for bullying both online and in real life, its prevalence is over 50%; the other reasons include race and ethnicity (over 30%), gender expression (about 22%), sexual orientation (19.4%), gender (18%), religion (18%), disabilities (12%) (2). Sexual harassment is one of the most common forms of bullying, its frequency is about 48%; LGBTQ teenagers are some of the most vulnerable targets for bullies. The latter tendency is dictated by the intolerance and prejudice of the adults who surround the youth (Riese). Differently put, the teenagers tend to act based on beliefs and ideas that were implicitly or explicitly promoted and put through to them since childhood. Starting to develop their own judgments, teenagers begin to practice the approaches of their parents and teachers as the basis for their own perspectives in life. As a result, the individuals and groups who are perceived as “other” or “different” become singled out as easy targets. In particular, in the tragic case of Ryan Halligan, the boys bullies used a rumor of him being gay as a means of shaming and embarrassing their victim, and artificially associating him with what was perceived as a disgraceful label. Thinking critically of the case, it is possible to notice that not only the bullies but Ryan himself were the carriers of a stereotype according to which belonging to LGBTQ is something one should be desperately ashamed of.

As a result of being cyberbullied, many teenagers report having the desire to skip classes, drop out of school, and engage in violent and aggressive activities in response to bullying (Anti-Defamation League 2).

Some of the effects of cyber- and regular bullying in teenagers are the abuse of alcohol to which teenagers draw attempting to cope with stress (15.6% prevalence), panic disorder (13%), depression and anxiety (10% each); the same effects tend to occur in the offenders; in fact, alcohol abuse incidence is much higher among bullies than their victims (almost 23%) (Anti-Defamation League 2). Some of the bullied teenagers demonstrated signs of diminished academic performance, substance use, stress, suicidal thoughts, social anxiety, suicide attempts, and externalized hostility (Bottino et al. 471). The latter phenomenon indicates the cyclic nature of bullying (both offline and in reality). In particular, victims of bullying tend to become aggressive and violent thus initiating bullying behaviors of their own and victimizing others. The aggression and hostility in bullying victims may be dictated by the attempts to create a scary and intimidating reputation or exterior so that they do not become targeted and hurt again. In that way, it is possible to theorize that every bully has an experience of being a victim at some point on their life.

Also, teens exposed to online bullying often reacts by blocking the bully, asking them to stop, or (if the attacks continue) deleting their accounts whatsoever. Moreover, the emotional responses of teens may differ significantly; namely, while some remain calm and indifferent, others become depressed, stressed, upset, and lose their confidence. The most common reaction to cyberbullying is anger as it occurs in over 56% of cases, 33% of victims feel hurt, 32% experience embarrassment, and one in eight teens (13%) report being scared of their bullies (National Crime Prevention Council 3). At the same time, informing an adult is one of the least common reactions to cyberbullying; about one in ten children respond in such way (National Crime Prevention Council 3).

How Cyberbullying Can Be Addressed or Prevented

As an outcome of rare incidence of the cases of cyberbullying reported to parents and caregivers, a high percentage of online attacks remain unreported leaving the adults powerless as the authorities helping to prevent the behavior (PACER Center 1-3). Unfortunately, teens are more likely to speak about being cyberbullied to their friends rather than adults.

However, there are a number of ways that parents could use to help their children cope with negative experiences online. For instance, NCPC recommends that the parents teach their children to ignore bullies, avoid taking revenge for being attacked, report bullying to special services online such as website moderators and the Internet service providers, protect their private information and passwords, realize the importance of contacting adults about cyberbullying, keep track of the attacks and seek help of the law enforcement if they become especially aggressive (2-3). In addition, parents of teens are advised to maintain close communication with their children and stay aware of their activities online, document the discovered threats by saving the conversations and printing out screenshots (PACER Center 3-4). It is critical that the parents of teens observe their children’s emotional states often and monitor the potential periods of distress and depression; since children are highly emotional at this age, parents could definitely notice the emotional change when their children suffer from cyberbullying and start acting on this situation right away.

Also, remembering the case of Ryan Halligan, it is important that the parents constantly warn their children about the dangers of sharing their private information in the internet. Finally, it is highly important for the adults to recognize the risks related to cyberbullying and treat it as a serious issue (Hinduja and Patchin 4). The same recommendation applies to the law enforcement authorities and the society in general as there is a pattern powering the normalization of cyberbullying and hate crime online (Citron 73). In particular, many victims of bullying leave their experiences unreported because there is a belief that bullying online is “not real” and that it cannot be harmful. Moreover, there is a popular idea that cyberbullying is one of the essential aspects of the Internet and one cannot enjoy its benefits without putting up with its disadvantages. Also, the children need to be educated about the mechanisms involved in such behaviors, the trolls whose goals are to provoke people and initiate fights for the sake of the content, virality, and popularity (Kobek 45).

Fieldwork: Interviews with Six Teenagers

In order to connect the review of literature planned for this research to real life scenarios and practices, it was decided to add interviews with teenagers and their experiences with cyberbullying. Five participants were selected for the interviews. Their consent, as well as the consent of their parents, was obtained prior to the interviews. The names of the interviewees will be changed for the purposes of anonymity but their genders will not.

Interviews

The interviews were conducted with each participant individually and face-to-face. The answers were written down for further analysis. The questions were focused on the teens’ experiences of being cyberbullied or witnessing someone being attacked online, the prevalence of this behavior, the personal initiation of cyberbullying, reactions, and the forms of cyberbullying they had encountered.

Findings

Incidence of Cyberbullying Reported by the Participants

Five out of six interviewees stated that they have experienced cyberbullying over the past week; three teenagers reported having been bullied within one week; one teenager stated that he was rarely attacked online. Five out of six respondents also said that they were often aware of the identities of their offenders, and in the vast majority of cases they were other children from this schools; only one respondent stated that he was attacked primarily by strangers. However, all of the teens reported receiving rude comments online, engaging in arguments and verbal fights, and having diminishing remarks in comments to their pictures on social networks.

One of the interviewees (Anne) said: “it happens so much that we don’t really pay attention to it anymore”. Another respondent (Jaden) noted: “Some people just say means things without reasons, I think everyone is used to it, it’s the Internet”. These responses indicated that teens are emotionally prepared to face criticism or bullying in cyberspace and perceive it as a part of the Web.

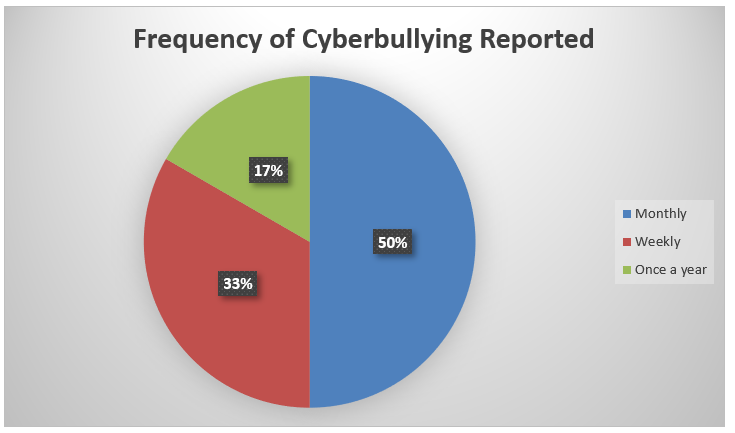

Three out of five respondents reported that they tended to become victims of cyberbullying at least once a month; one states that she was targeted weekly; and one said he had only been a victim several times in his life.

Offenders and Offending

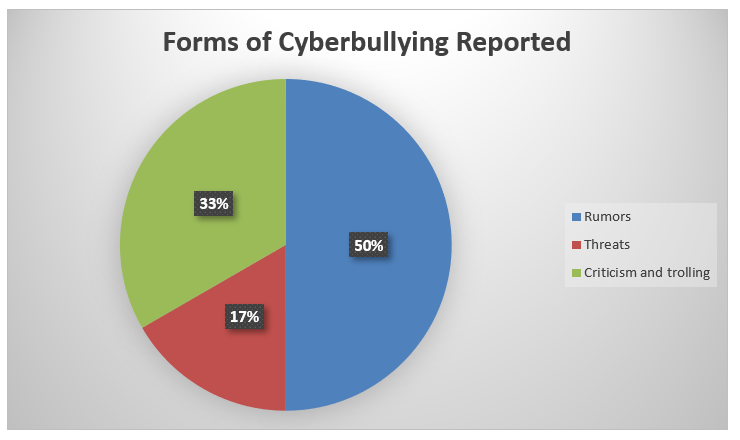

When asked about personal attacks, five out of six respondents admitted having been targeted by their peers; also, the reported online bullying attacks came in several different forms. The most common form of bullying online was rumors (reported by 3 teens), criticism and trolling came second (reported by 2 teens), one person reported receiving threats.

Moreover, all of the respondents recalled witnessing multiple cases of cyberbullying.

Henry: “Two of my friends had a fight because someone wrote lies about someone. They are no longer friends”.

Sara: “I see it every day – people fighting online, people threatening one another, using very rude words. Strangers, classmates, friends, boyfriends and girlfriends – the status doesn’t matter”.

Maria: “Some guys from my school do it as a hobby. They just go on people’s Facebook pages and leave those comments. I don’t know why, I think it’s how they have fun”.

Also, two out of five teens stated that they had experiences of bullying other people online. The following answers were given as explanations of their reasons for this behavior:

Jaden: “This girl is just so annoying and stupid, everyone is laughing at her. My friends sent me a link to her Facebook pictures where she looked awful, so we mocked her. And then we found out that she was crying about it.”

Anne: “It was my response to some girl’s mean comments about me, she was spreading gossip, she said things…. So my friends and I did the same to her. We wrote embarrassing stuff about her and called her names.”

None of the respondents reported speaking to adults about being cyberbullied, even if the magnitude of the attacks was very powerful.

Conclusion

In “I Hate the Internet”, Kobek explored the shock faced by the users of the Web due to the unlimited opportunities for harassment and assault it brought. While for the adults living in the era of the establishment of the Internet, it was an overwhelming experience, the children growing up as the users of the Web can and should be emotionally prepared for the negative sides of it such as cyberbullying. In particular, the modern teenagers report a very high incidence of cyberbullying that makes almost every child a victim on a regular basis. Some of the users are accustomed to violence online and can cope with it; however, most tend to become triggered and engaged by it, getting sucked in the destructive behaviors leading to even more harm.

Works Cited

Anti-Defamation League. “Statistics on bullying.” ADL, 2016. Web.

“Ages 15-18: Developmental Overview.”ParentFurther, 2017. Web.

Bottino, Sara Mota et al. “Cyberbullying and adolescent mental health: Systematic review.” Cadernos de Saúde Pública, vol. 31, no. 3, 2015, pp. 463-475.

Citron, Danielle Keats. Hate Crimes in Cyberspace. Harvard University Press, 2014.

Hinduja, Sameer, and Justin W. Patchin. “Cyberbullying: Identification, prevention, & response.”Cyberbullying, 2014. Web.

Kobek, Jarett. I Hate the Internet. Serpent’s Tail, 2016.

National Crime Prevention Council. “Teens and cyberbullying.” NCPC.org, 2007, Web.

NCPC. “Stop cyberbullying before it starts.” NCPC.org, n.d., Web.

Notar, Charles E. et al. “Cyberbullying: A review of the literature.” Universal Journal of Educational Research, vol. 1, no. 1, 2013, pp. 1-9.

PACER Center. “Cyberbullying: What parents can do to protect their children.” PACER, 2013. Web.

Riese, Jane. “Youth Who Are Bullied Based upon Perceptions about Their Sexual Orientation.” Violence Prevention Works, 2016. Web.

“The Top Six Unforgettable CyberBullying Cases Ever.” NoBullying.com, 2017. Web.