Description of the Case Study

Rachel, a 15–year–old girl, was diagnosed with cyclothymic disorder. The disorder is considered as a relatively mild type of bipolar II. Rachel displays a wide range of symptoms, including mood swings that could appear normal. Rachel often show mild depression, a low-level mania and certain emotions (periods of extreme creativity, energy, and/or irritability) associated with hypomania. While cyclothymic disorder may remain undiagnosed or persons may be unaware of their conditions and possible treatment options, Rachel was successfully diagnosed with the condition. Nevertheless, changes in the mood were observed throughout her condition, and Rachel was never free from one or more of her symptoms.

Clearly, Rachel requires both short-term and long-term management of cyclothymic disorder because her condition is a lifelong disorder that is complicated by high comorbidity and challenges of poor health outcomes. As such, primary care clinicians have a critical role to play in enhancing the quality of life of Rachel. On this note, the management plan for the condition, specifically for severe mood behaviors should aim for safety of Rachel. This process may entail immediate consultation when necessary. Moreover, Rachel may require an evidence-based intervention immediately, which should be extended to maintenance stages. In addition, the patient will also require long-term management to control mood, constant medication and further psychotherapy support to improve her quality of life.

An Evidence-based Psychiatric Assessment

Researchers have observed that misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents has become a common public health issue (Jenkins, Youngstrom, Washburn, & Youngstrom, 2011). While accurate diagnosis is vital, it is often difficult and thus leading to errors. As such, evidence-based assessment (EBA) methods are viewed as alternatives that could assist in enhancing diagnostic accuracy.

A nomogram assessment has been effectively applied in assessing adolescent cyclothymic disorder. The nomogram shows that information regarding family history can be applied to assess the condition in a quantitative manner. In the case of the nomogram assessment, EBA promotes the application of Bayesian strategies for evaluating the likelihood of a person having the condition. Bayesian approaches usually link new data with the earlier probability of an assessment in order to approximate a reviewed, posterior probability (Youngstrom, Freeman, & Jenkins, 2009).

The line located in the middle of the nomogram is used to quantify the outcome of the new pieces of data assessed. They are computed as “diagnostic likelihood ratio” (DLR), which theoretically indexes the observed variation in risk of cyclothymic disorder by gauging the rate at which the assessment procedure takes place. Usually, rates related to higher test scores or positive family history are compared against rates found in cases without cyclothymic disorder. That is, the DLR depicts the sensitivity ratio obtained from cyclothymic disorder assessment. In this case, from 100 samples of individuals with the disorder, the assessment focuses on individuals who will get positive evaluation results. This number is then delineated from the false alarm rate. That is, from 100 individuals without the condition, the number that would falsely get positive assessment outcome is determined. The DLR generally captures the deviation in the odds of being a cyclothymic disorder diagnosis. The nomogram is formulated to eliminate the need to conduct analysis to link the preliminary probability with the DLR. Rather, the clinician obtains the DLR from the value noted in the middle of the nomogram column and then relates the dots found between the initial line and the subsequent line (the DLR). They further stretch the line to the third line on the right-hand value of the nomogram. This will provide the reviewed probability estimate.

One major challenge surrounding the diagnostic testing is that results may be misinterpreted. Misinterpretation is mainly common when clinicians consider test findings as printed statements regarding the patient’s condition. The nomogram is however designed to improve on such errors.

Research currently shows that when clinicians only rely on family history or use it as if it is the same as the cyclothymic disorder diagnosis in a patient, then about three cases would be inaccurate from four cases evaluated (Youngstrom et al., 2009). In this case, it is shown that family history may not be diagnostically beneficial for some patients because even if such a condition is present, some adolescent may still not have cyclothymic disorder. According to Youngstrom et al. (2009), when performing a sensitivity analysis with two varied estimates of risk, outcomes are reliable in demonstrating that this specific combination of “factors put the youth at moderate risk (24-39%) of having a bipolar spectrum illness” (p. 353). These results confirm the observation that positive family history could be misleading and, therefore, further comprehensive assessment of potential mood disorder is necessary.

Obviously, EBA decision support tools, such as the nomogram, could result in an imperative declining misdiagnosis and assist clinicians to assess and detect actual cases of cyclothymic disorder (Jenkins et al., 2011).

It is imperative to recognize that no single element of assessment of cyclothymic disorder or other bipolar conditions have been ‘perfected’. Hence, currently available assessment tools could be improved, and every assessment strategy provides a chance for improvement (Jenkins et al., 2011).

Laboratory or Other Diagnostic Screens/Tests that are Appropriate for the Case

Clinicians generally rely on the criteria provided by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) to diagnose bipolar disorder (Meter & Youngstrom, 2012). They focus on manic, depressive, or a combination of both factors, frequencies of occurrence, and periods. Physicians must therefore determine the exact cyclothymic condition by eliminating other conditions with similar symptoms such as bipolar I or II, depression, or another mental condition that could be responsible for the symptoms (Barnhill, 2014). Doctors therefore conduct multiple examinations and tests.

Physical examination and laboratory tests are conducted to assist in identifying any possible medical issue that could be responsible for the symptoms.

Psychological assessment involves the evaluation of the patient’s thoughts, behavior patterns, and emotions using questionnaires (Sadock, Sadock, & Ruiz, 2014). In addition, patients or family members provide information on depressive or hypomanic symptoms for differentiation from other conditions.

Physicians also conduct mood charting to determine daily swings, sleep patterns or any other factors related to moods that could assist in accurate diagnosis and determining the best treatment alternatives.

Diagnostic criteria for cyclothymic disorder, as provided by the DSM-5, focus on specific areas. First, physicians assess cases of elevated mood and other depressive symptoms for at least a year in the case of adolescents. Second, they also evaluate stable moods noted not more than two months. Third, they also assess impacts of such symptoms on social life at school or any other relevant places. Fourth, physicians must determine that such symptoms do not meet DSM-5 criteria for bipolar disorder, unipolar disorder, mania, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), schizophrenia, depression, or any other mental disorders. Finally, they must test for possible medical condition or substance abuse against the symptoms.

Further, adolescents such as Rachel also requires laboratory tests for drugs or alcohol abuse, as well as blood tests for thyroid activities.

The Young Mania Rating Scale (P-YMRS) parental version has been noted as an important tool in assessing bipolar disorder in children and adolescents (Marchand, Clark, Wirth, & Simon, 2005). The screen instrument consists of 11 multiple-choice questions focusing on mood, energy level, sexual interest, sleep, irritability, rapid speech, thought pattern fluctuations, grandiosity and/or hallucinations, aggression, appearance change, and insight about the need for intervention. Every question consists of five multiple-choice answers, and parents circle zero in case the child lacks any symptoms. For Rachel, the mark would not be zero, but she will have positive answers that range from 2 to 4 for seven questions, 2 through 8 for the rests of the four questions. Parents then add scores from every question to determine the aggregate score. Adolescents with relatively higher scores reflect superior symptom severity. One would expect Rachel to score relatively higher to reflect her greater symptom severity based on her condition.

Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale (RADS) may also be used in the case of Rachel to determine a possible depression. RADS was developed for persons aged between 13 and 18 years old to diagnose adolescents with symptoms associated with depression, but not any other specific disorder (Platt, 2001). The screening tool contains 30 items with a weight that ranges from 1 to 4 (in which choices range from almost never to most of the time). The least score is 30 while the highest is 120. A cutoff total score was set at 77 to determine a patient for further assessment. This score reflects the level of symptom manifestation linked to clinical depression. Since Rachel is cyclothymic disorder patient, she is most likely to score less than 77 aggregate points.

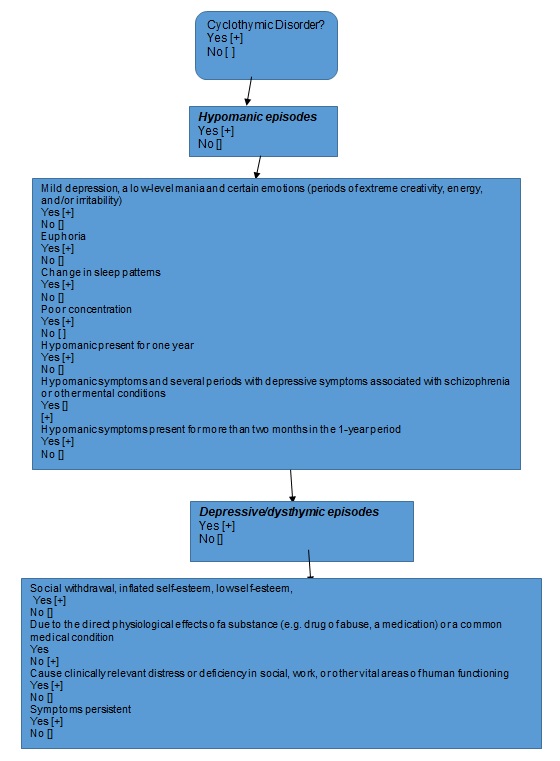

A Decision Tree to Illustrate the Presenting Symptoms and Possible Differential Diagnoses

Diagnosis of cyclothymic disorder remains complicated due to several factors. The depressive-dysthymic instances noted in cyclothymic disorder are also considered as major diagnostic symptoms in several mental disorders such as psychotic disorders, ADHD, behavior adjustment disorder and other mood conditions. Life events and conditions may trigger depression. Therefore, clinicians must determine when depression is considered relevant for cyclothymic disorder.

First, as previously noted, cyclothymic disorder has formally defined criteria to ensure that symptoms of bipolar disorder not found within the DSM-defined subcategories are identified. In the case study, the patient, an adolescent, must meet differential diagnosis of cyclothymic disorder by experiencing at least a one-year period of hypomanic symptoms and other depressive symptoms without displaying symptoms for mania or major depression (Meter & Youngstrom, 2012). Conversely, BP NOS diagnosis is only applied for patients who experience symptoms associated with hypomania and/or depression, which fail to meet criteria required for major depression or mania. It is therefore understandable when clinicians use a common diagnosis of BP NOS when assessing cyclothymic disorder. It is noteworthy that many physicians face difficulties with the criteria for cyclothymic disorder. In particular, it is difficult to differentiate chronic symptoms of cyclothymic disorder from temperamental variations in adolescent and children. Usually, diagnosis for mood disorder relies on a distinct episode, but cyclothymic disorder needs at least a single year of episode. Therefore, timing of symptoms and related details could be difficult. Even so, it could be difficult for clinicians to obtain reliable patient information on the condition. In addition, evidence suggests that reflective reporting is particularly fallible, and when assessing symptoms observed for the last one year, it can be difficult for parents or patients to outline a year-period episode. Furthermore, it could be equally difficult to note whether hypomania symptoms, including euphoric mood, irritability and increased energy, are pathological or they are related to signs associated with active children. In such an instance, clinicians may opt for ADHD diagnosis. ADHD is normally associated with euphoric mood, depression or low mood.

Second, cyclothymic disorder diagnosis is complicated because of the overlapping diagnostic criteria for other mental disorders. In adolescents and young adults, for instance, borderline personality disorder symptoms could be confused with cyclothymic disorder symptoms, or strange depression. These mental disorders are usually associated with critical irritability and mood instability while in some instances they may have similar fundamental cyclothymic disposition and therefore resulting in a difficult differential diagnosis. In adolescent, depression and ADHD could have the same characteristics, such as restlessness, irritability, and mood swing among others, as cyclothymic disorder. Besides, cyclothymic disorder is less common relative to depression and ADHD. As such, most physicians may have experience diagnosing and managing ADHD and/or depression in adolescents. Therefore, clinicians should focus more on periods of elation and elevated self-esteem as differential diagnosis rather than concentration and memory symptoms noted in ADHD.

Finally, cyclothymic disorder is generally comorbid with other mental conditions – a situation that makes diagnosis extremely difficult (Danner et al., 2009). As such, researchers have failed to agree on the relationship between cyclothymic disorder and other bipolar disorders. In regular clinics focused on symptoms and immediate treatment, cyclothymic disorder diagnosis is most likely not to be used even if it is the accurate choice for diagnosis because of uncertainties created by overlapping symptoms of other mental disorders.

A DSM V Provisional Diagnosis or Diagnosis/s as Appropriate

The DSM V for cyclothymic disorder diagnosis is used in cases of patients who have suffered mood change for over two year, but they do not meet diagnostic criteria applied for assessment of bipolar I, bipolar II, or depressive disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Based on the DSM V, there are six diagnostic provisions for cyclothymic disorder. First, in the last two-year period, the patient has experienced episodes of hypomanic and depressive symptoms that do not qualify for full DSM V diagnostic criteria for significant depressive or hypomania disorder (First, 2014). Second, episodes of hypomanic and depressive symptoms have been observed for at least half the time during the two-year period, but with sustained two months symptoms presence. Third, the patient lacks history of diagnoses for hypomanic, manic, or a depressive symptom. Fourth, the psychotic disorder, including schizophrenia, delusional disorder and others cannot explain episodes of hypomanic and depressive symptoms that do not meet diagnostic criteria for other mental disorders. Fifth, substance abuse or medical condition cannot explain the observed symptoms. Finally, the symptoms observed have significantly poor influence on social and work life.

Clinicians should also consider anxious distress as a specifier. In children and adolescents, the DSM V notes that the observational period is one year, and two years for adults (McVoy & Findling, 2013).

Under the DSM V diagnosis, substance abuse related disorders are comorbid with cyclothymic disorder because people with mood disorders are most likely to use alcohol or drugs during self-medication and attempts to alleviate symptoms. Similarly, comorbidity is also noted with sleep disorders associated with poor start and maintenance of sleep. In adolescent and children, comorbidity is linked to ADHD, but clinicians must carefully assess ADHD because of overlapping symptoms.

Evidenced-Based (EB) Interventions

Studies have shown that adolescent with symptom profiles presented for diagnostic symptoms for cyclothymic disorder show that bipolar subtypes react to pharmacological interventions in a similar manner. Medications such as lithium and other anticonvulsants such as antipsychotics are used to stabilize patients’ mood. In fact, the Improving the Assessment of Juvenile Bipolar Disorder research established that adolescent cyclothymic disorder was treated effectively with psychotropic medication such as lithium, antidepressants, antipsychotics (both typical and atypical), mood stabilizers, anticonvulsants and stimulants (Meter & Youngstrom, 2012). It is however observed that pharmacological interventions for cyclothymic disorder may not be consistent based on the choice of medication. Hence, there is a need for sufficient pharmacological interventions for the disorder. While there is little scientific evidence for pharmacological interventions, cyclothymic disorder responds to medication in a similar manner as other bipolar disorders and, therefore, treatment approaches should be developed based on the available algorithm to increase outcomes. Anti-depressants should not be used as monotherapy because they generally initiate mood changes, possible treatment resistance, and mixed experiences associated with cyclothymic disorder (Parker, McCraw, & Fletcher, 2012; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2007).

Psychotherapy can be used to improve patients’ outcomes. These interventions may include cognitive behavioral therapy, group therapy, and interpersonal therapy among others. Clinicians should consider the level of intervention based on the stage of the condition. Tertiary intervention is used in patients with the manifested disorder (Youngstrom et al., 2009). In this case, tertiary intervention works well for patients with determined cases and are at high risk. The ‘levels of intervention’ is considered as evidence-based medicine (EBM), and various models can be combined to evaluate and treat bipolar disorder based on moderate risk categorization (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, n.d).

It is imperative to note that both pharmacological and psychotherapy interventions for cyclothymic disorder have received different amounts of support. Therefore, the most effective treatment should be used to help with the disorder (Bisol & Lara, 2012).

Diet and sleep management are considered as lifestyle factors for managing the condition. While healthy diets are recommended for all individuals, persons with bipolar disorder should maintain healthy diets and restrict calories to control weight gain. Moreover, foods rich in omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are known to manage symptoms of various mental conditions, including bipolar disorder (University of Maryland Medical Center, 2016). Hence, omega-3 fatty acid supplements are important for Rachel. Effective sleep hygiene, as a part of sleep management, is necessary for bipolar disorder patients because healthy sleep is used to control mood cycling.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (n.d). Bipolar disorder: the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. Web.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. (2007). Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Bipolar Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(1), 107-125.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Barnhill, J. W. (2014). DSM-5® Clinical Cases. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bisol, L. W., & Lara, D. R. (2012). Low-dose quetiapine for patients with dysregulation of hyperthymic and cyclothymic temperaments. Psychological Medicine, 24(3), 421–424. Web.

Danner, S., Fristad, M. A., Arnold, L. E., Youngstrom, E. A., Birmaher, B., Horwitz, S. M.,… Kowatch, R. A. (2009). Early-Onset Bipolar Spectrum Disorders: Diagnostic Issues. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 271–93. Web.

First, M. B. (2014). DSM-5 Handbook of Differential Diagnosis. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

Jenkins, M. M., Youngstrom, E. A., Washburn, J. J., & Youngstrom, J. K. (2011). Evidence-Based Strategies Improve Assessment of Pediatric Bipolar Disorder by Community Practitioners. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(2), 121–129. Web.

Marchand, W. R., Clark, S. C., Wirth, L., & Simon, C. (2005). Validity of the Parent Young Mania Rating Scale in a Community Mental Health Setting. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 2(3), 31–35.

McVoy, M., & Findling, R. L. (2013). Clinical Manual of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology (2nd ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Meter, A. R., & Youngstrom, E. A. (2012). Cyclothymic disorder in youth: why is it overlooked, what do we know and where is the field headed? Neuropsychiatry (London), 2(6), 509–519. Web.

Parker, G., McCraw, S., & Fletcher, K. (2012). Cyclothymia. Depression and Anxiety, 29(6), 487–494. Web.

Platt, M. M. (2001). TEST REVIEW: Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale. Web.

Sadock, B. J., Sadock, V. A., & Ruiz, P. (2014). Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry (11th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

University of Maryland Medical Center. (2016). Bipolar disorder. Web.

Youngstrom, E. A., Freeman, A. J., & Jenkins, M. M. (2009). The Assessment of Bipolar Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 18(2), 353–9. Web.

Appendix

Decision Tree for Cyclothymic Disorder