- Causes of Fiscal Stress in the States

- Structural Budget Imbalance

- Symptoms of Fiscal Stress in the States

- Consequences of States’ Fiscal Stress on municipal governments

- States Responses to Local governments’ Fiscal Stress

- Federal Responses to States Fiscal Stress

- Responses of State governments to Fiscal Stress

- Summary

- Conclusion

- References

The government’s lack of ability to balance its budget is fiscal stress. It creates a state of disparity in provisions of government services and the inability to cater for such services.

According to Mouritzen, fiscal stress creates a situation in which to “balance the budget, a government must increase taxes, reduce real expenditures or engage in some combination of the two” (Mouritzen, 1992). Schick noted that the government also experiences scarcity of resources in its budgeting (Schick, 1980).

This is because the public needs several services, but their willingness to pay for such services are low. Consequently, fiscal stress is always present in budgets of governments. However, it is the fluctuation of such resources in government’s budgets that differs among governments.

Levine noted that states and local governments should be in charge of balancing their budgets on an annual term. According to Levine, responsibilities of balancing budgets at the local levels make symptoms of fiscal stress identifiable at local government levels than at the federal government level (Levine, 1980).

The state government and local authorities may use different services they provide to the public to measure the level of fiscal stress. They look at the imbalances that occur when providing services and receiving funds for such services.

In addition, the need to spend and resources available do not match in most cases. For instance, the State of Michigan may experience difficulties in provisions of public facilities to its rising population.

A number of studies have emerged to address challenges which result from difficulties in measuring local government fiscal situations (Kloha, Weissert and Kleine, 2005).

As a result, studies base fiscal stress indicators on decisions of the local government and underlying economic situations, which cause fiscal crisis (Skidmore and Scorsone, 2009).

Causes of Fiscal Stress in the States

The state can experience both “short-term (transitory economic shock) and long-term (structural budget imbalance) fiscal stress” (Congressional Budget Office, 2010). These conditions may create a gap between the projected revenues and expenditures.

Transitory Economic Shocks

When economic situations are weak, the local government reduces its tax revenues and the state government reduces aid. There is an increase in demands for public services and loss of investment opportunities. Local governments rely on a stable source of revenue (property taxes).

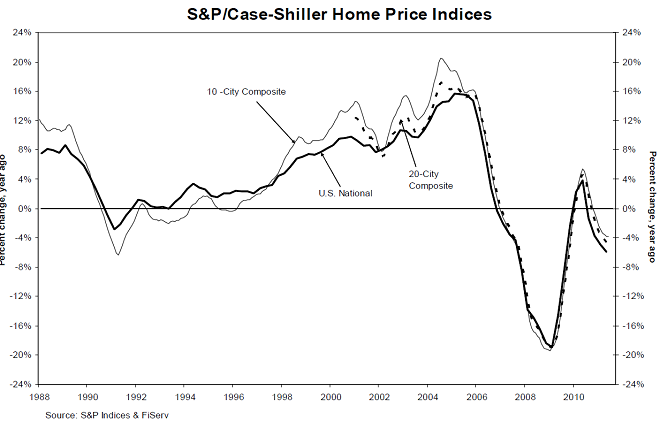

This makes them experience minimum effects of fiscal stress than state government that depends on revenues from sales and incomes. For instance, in 2006, house prices fell by 27 percent.

This implies that the property collections shall fall in the coming years as the local government shall adjust its property tax systems to reflect the market standards (Feldman, Courant and Drake, 2003).

Thus, any decline in the collection of taxes shall cause fiscal stress as demands for public services increase (Pagano, Hoene and McFarland, 2012).

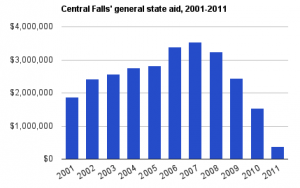

The state government provides “30 percent of revenues to local government” (Congressional Budget Office, 2010). However, this shall also reduce as income and sales taxes also drop.

The decline in state revenues also implies that the state government must cut its spending partly by reducing the amount spent on local governments. Both states and local government fiscal stress occur at the same time.

Consequently, states also reduce their aid when local governments also need it for provisions of public services. Some 31 governors had proposed to reduce spending on K-12 education due to decline in revenues (Congressional Budget Office, 2010).

Source: House Fiscal Office, 2012

States have a number of options in reducing their aid to local governments. These include education, Medicaid, and other services states can fund partially.

Economic downturns normally lead to increase in demands for public services due to unemployment and reduced work schedules associated with loss of health insurance.

Thus, these people turn to public services such as health facilities, public transport, libraries and social welfares for free or discounted services. There are also issues of crimes, which put pressure on police (Congressional Budget Office, 2010).

Structural Budget Imbalance

Long-term causes of fiscal stress are multifactorial. However, a common source of structural budget imbalance is the political situation at the local, state, or federal level. Different views emerge and affect the agreement on a budget.

Public unions and employee groups may also cause deficit. For instance, in California, Vallejo filed for bankruptcy based on “the inability of the mayor and the council to control costs of labor” (Congressional Budget Office, 2010).

Bankruptcy is a rare case but occurs for diverse reasons. The City Council increased wages and benefits of its public officials and ignored warnings to stop such practices.

Changes in demographic characteristics also cause fiscal stress. For instance, a high income household may move from an area and cause long-term imbalance in the budget. Such changes may involve transferring a business to other areas. This translates to a drop in the jurisdiction’s tax incomes.

Lack of proper financial control systems can also cause long-term fiscal stress in a state. In New York, questionable accounting method led to concealment of increasing deficit to the extent that it was beyond financing by the financial market.

Effective budgetary control should focus on debt, expenditure limits and balanced budget control. There should be regular auditing and oversight committees to regulate financial practices for transparency and accountability (Congressional Budget Office, 2010).

In some cases, fiscal stress may result from borrowing by the local government. Short-term debts may alleviate deficit in a budget. However, if the local government spends more that it can collect, then it may face fiscal stress in the future.

Symptoms of Fiscal Stress in the States

According to a study by Ivacko, Horner, and Crawford, the condition of fiscal stress of Michigan State has shown positive trends despite the widespread distress (Ivacko, Horner and Crawford, 2012).

Some of the symptoms of State of Michigan fiscal stress included a decline in property tax revenues, state aid, increase in demand for public services, and challenges with health care costs.

Decline in property tax revenues

The report reflects positive gains. However, Michigan State has serious fiscal distress. Property tax revenues are on the decline. This is the most crucial source of funding for the local government. The situation was severe in 2009 due to effects of recession.

The trends indicated declines in property tax revenues in various areas of Michigan. For instance, local governments of Upper Peninsula expressed optimism (35%) whereas those in the south regions showed high-levels of difficulties (81%).

Some regions in Michigan indicated growths in property tax revenues. About 17 percent indicated that the revenue had increased as compared to the previous year. However, the growth in property tax in Michigan remains sparsely distributed.

Decline in state aid

The decline in state aid is a major problem to most local governments. It affects 42% of Michigan jurisdictions. The decline in state aid usually affects large jurisdictions of Michigan where it was 68% in 2012. Conversely, less populated areas only reported a decline of 35% in 2012 (Ivacko, Horner and Crawford, 2012).

In 2010, 2011, and 2012, there were 86%, 61%, and 46% of aid respectively among various jurisdictions of Michigan. This shows a declining trend in provisions of state aid.

Other jurisdictions reported declines whereas others reported increments in state aid. In 2011, state aid was 15% whereas in 2102 was 9%. The trend was only common in less populated areas.

Increase in demand for services

Local governments experienced pressure from increased demands for public services. There were increments in demands for health services (64%), human services, infrastructure (66%), and security (59%) than witnessed the previous year. This shows how fiscal stress is on the rise in Michigan.

Challenges in provisions of health care services

The increments in costs of health care remain a challenge to Michigan fiscal stress. Only 46 percent of the jurisdictions indicated that they had fringe benefits for their employees. In Michigan, small jurisdictions rarely provide health care to their employees.

This is because some employees are not full-time employees. The general trend is that health care costs in Michigan increased considerably from the previous years’ costs.

Effects of Fiscal Stress on State governments

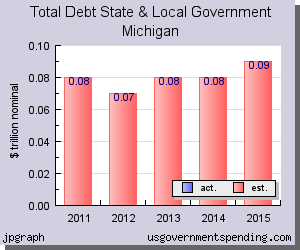

Fiscal stress of today is severe in Michigan and other states. Michigan has a budget deficit of $1.4 billion in the fiscal year 2012. As a result, the state has embarked on a tax balance in order to reduce challenges in its structural budget.

Decline in revenues due to tax cuts

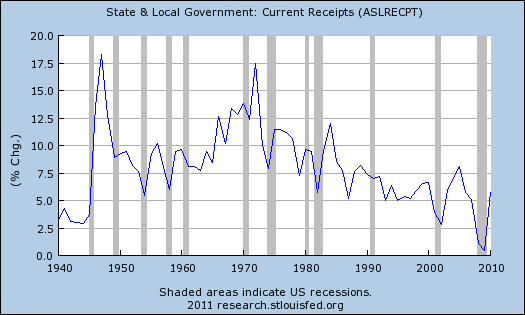

During 1990s, most states experienced growth in revenues. This was due to robust stock market, increasing consumption, and returns on capitals. However, recessions have changed these trends.

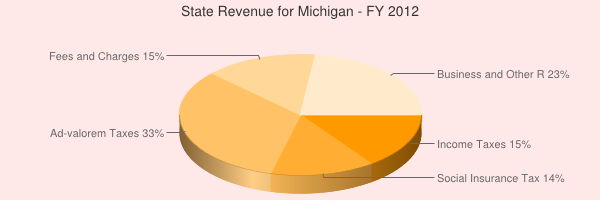

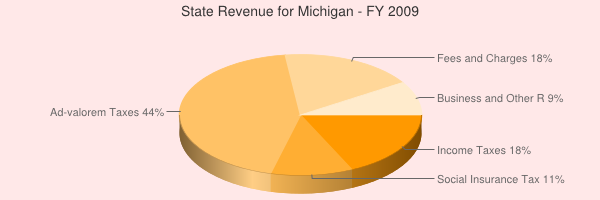

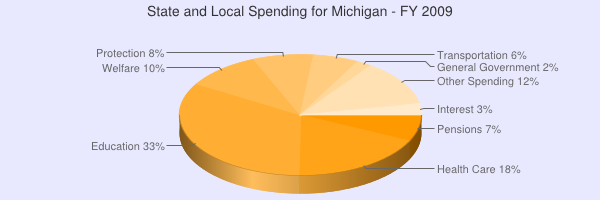

For instance, the decline in housing pricing led to tax cuts. These figures show the decline in State of Michigan revenues between 2009 and 2012.

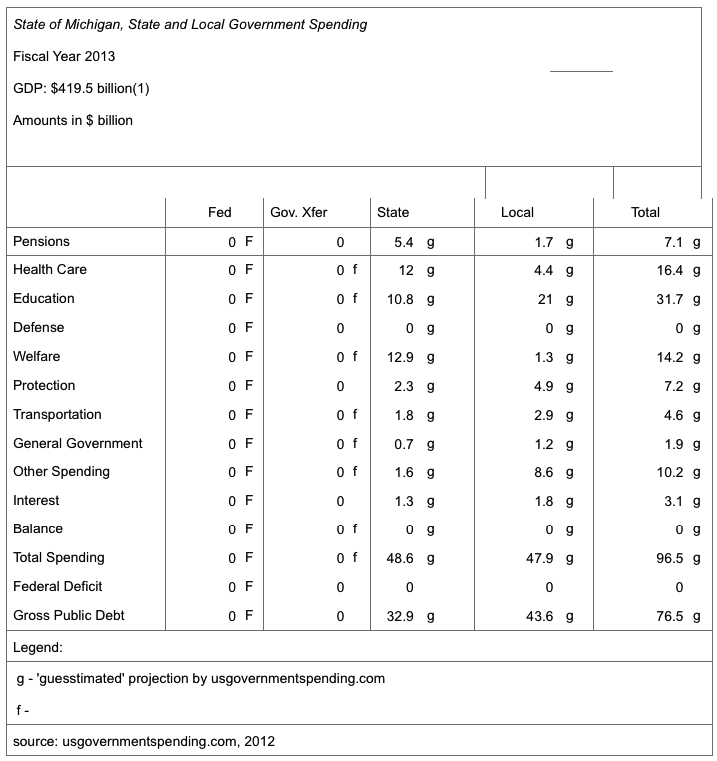

Source: usgovernmentspending.com, 2012

We can now see the effects of economic slowdown of 2008/9 on Michigan revenue growth and subsequent spending, and how it has created fiscal stress.

The long-term deficits in collections did not match economic growth of Michigan. States mainly depend on sales and incomes taxes. However, products subjected to taxes are on the decline due to slowdown in rates of consumption. Michigan has also noted the decline in state corporate income taxes.

This is because most firms have restructured to avoid hefty taxes from the state. Michigan has been relying on state income taxes. However, they cannot cover for the large deficits experienced from declining incomes and sales taxes.

Consequently, Michigan has tried to balance between reducing other taxes and increasing others coupled with reduction in spending on public services.

Decline in spending

Michigan has responded by cutting spending amidst the growing demand from the public (Reschovsky, 2004). This is an attempt to balance the revenue and the expenditure to reduce fiscal stress. Before 2003, most states had already turned to their rainy day reverses (McNichol, 2003).

However, they will be unable to do so due to procedurals barriers and limits. Consequently, tax increase and cutting spending are the only viable options.

Before the crisis of 2008/9, Michigan’s expenditure was already on the decline. This was not a mere crisis, but a serious fiscal deficit in the state. This trend is not likely to slow down soon. It will persist until the US economy improves.

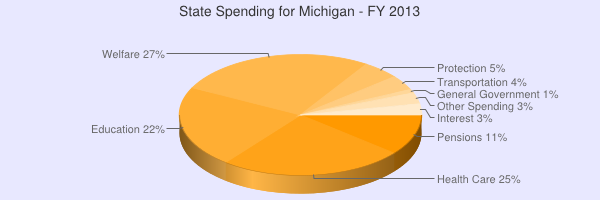

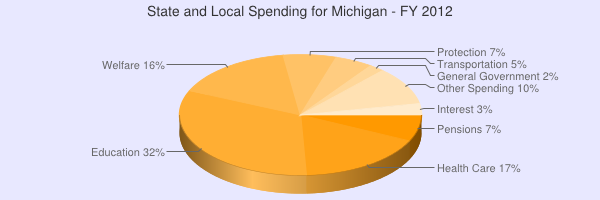

There is a general cut of spending on education (K-12). In 2009, Michigan spent 33 percent of its annual budget on public education. However, this figure has declined by 1 percent in 2012 to 32 percent.

In the 2012/2013 budget, Michigan reduced University funding by 15 percent ($222 million) to $1.2 billion in order to reflect the economic reality of the state (State of Michigan, 2011). A number of education programs maintained their levels of funding or experienced slight reduction.

The State of Michigan has also reduced spending on Medicaid and health care funding by one percent between 2009 and 2012. According usgovernmentspending.com, Michigan shall reduce education spending to 22 percent. On the other hand, the state shall increase health care to 25 percent.

Consequences of States’ Fiscal Stress on municipal governments

Michigan fiscal stress affected municipal governments in a number of ways. Some jurisdictions reported declines in state aid. As a result, such municipal authorities shifted to other methods of managing fiscal stress.

The state will allow schools, municipalities and other local authorities enough time to control their affairs (Congressional Budget Office, 2010).

Decline in spending

There has been a general decline in spending at the local levels by the state. The state budget recognized the need for a budget cut in order to restore fiscal solvency. There were declines in spending on education. Overall, support for schools declined by 8.4 percent in 2012 due to technical adjustments in the budget.

Health care spending also declined by one percent in 2012 compared to the previous year. This decline occurred due to changes in tax rate. Michigan estimates that the cost of health care services shall increase to 33 percent in 2013 (State of Michigan, 2011).

These changes occur due to decline in “contribution to pension funds and health care funds” (State of Michigan, 2011). They also experience delays as fiscal stress persists. Michigan also noted that changes in tax collection shall affect both public and private pension incomes.

For a long time, Michigan has exempted some parts or all of pension income from tax. However, due to escalating fiscal stress, declining population, and the increasing number of senior citizens, the state believes that it is now impossible to exempt any segment of the population from supporting public services.

The state shall tax pension income. However, it will exempt social security benefits from any tax.

Increasing Taxes and Fees

In 2003, Finegold, Schardin, and Steinbach noted that states adopted various methods of responding to fiscal stress (Finegold, Schardin and Steinbach, 2003). These methods had effects on municipal governments.

One of the responses was to “increase taxes and fees so as to manage fiscal stress” (Congressional Budget Office, 2010). A combination of changes in the tax structure helped Michigan ease fiscal stress in 2012 as studies suggest.

Such taxes and fees make up for losses incurred during previous years. Michigan state budget of 2012/2013 changed its tax structures and allowed time for municipal authorities to adjust their operation.

Timing of Public services and Tax increase

Apart from increasing taxes and fees, local governments have also reacted by postponing payments and changes in enacting tax measures.

For instance, in 2003 Michigan proposed increments in taxes from business, gambling, and cigarette sales. These were temporary measures, spending solutions, and revenue generation strategies.

The state also decided to cut SCHIP, and postpone its planned increment. At the same time, it also cut spending on TANF.

Borrowing

Michigan State budget estimate for 2012/13 indicates that it shall borrow short-term funds to schools. This shall increase from the current $20 million to $ 30 million in 2013. This is a method of coping with fiscal stress at the municipal levels which require these services.

Short-term borrowing is common among local municipalities because it can fund operating deficits. On the other hand, states prefer using “long-term debts to fund capital budget and health care programs” (Dilger, 2011).

States Responses to Local governments’ Fiscal Stress

Michigan State has assisted “local governments that have experienced fiscal stress over the years” (State of Michigan, 2011). For instance, it has increased aid in some jurisdictions and collection additional tax.

However, the state has not taken any local government for oversight purposes or financial operation of the jurisdiction.

Before any local government adjusts its taxes and spending upwards, it seeks for aid from Michigan State. Ivacko, Horner, and Crawford observed that Michigan State increased aid in some of it jurisdictions in 2012. More than 15% reported increased aid from the state.

In 2011, this figure was 9%. Areas, which received increased state aid, were mainly mid-size localities with 5,001 and 30,000 people.

In 2012, Michigan State shared a total of $25.5 million or 4 percent of its budget with cities, villages, and townships using estimated tax collections.

The state had the option of “redistributing revenues from various states to those which experienced shifts in populations” (State of Michigan, 2011). Such changes in populations create imbalances in revenue collections.

Michigan also adjusted taxes across various jurisdictions in its 2012 fiscal budget. This approach aimed at attracting business communities and discouraging people from moving to new localities.

In some cases, the state “reviewed taxes that local government imposed in order to increase high rates of taxes” (Congressional Budget Office, 2010).

Michigan sought to invigorate its economy through a tax structure that is “fair, simple, and efficient” (State of Michigan, 2011). The state needed participation of all citizens to fiscal stress.

Federal Responses to States Fiscal Stress

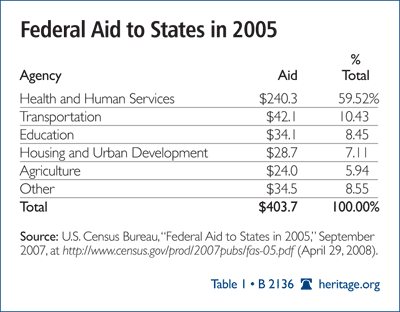

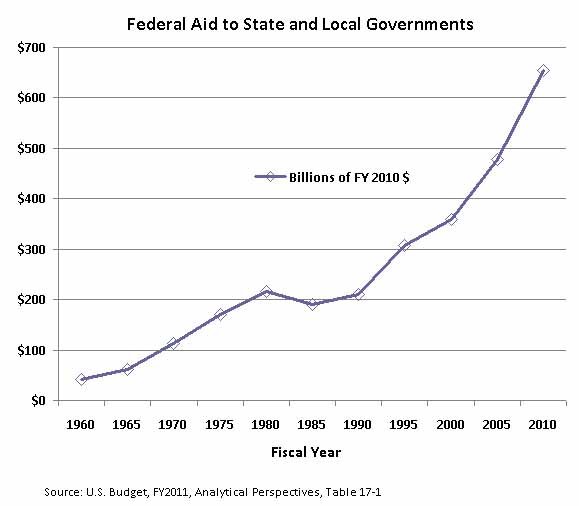

The federal government has the responsibility of assisting state governments with “grants, debt guarantees, loans, and other areas applicable through the tax code” (Dilger, 2011). Local governments depend on the state for power. However, the US Constitution protects states from interferences from the federal government.

Thus, it cannot introduce oversight bodies or force states to correct their challenges with fiscal stress. In this sense, the federal government has conditions that it attaches to aid given to state governments.

Federal government can give both direct and indirect aid to states. Directly, it is through funds or other forms of aid. Indirect aid may come in form assistance to a local entity.

For instance, in 2008, the federal government spent only 4 percent as state aid directly. However, forms of indirect aid from the federal government are difficult to quantify as there are no available data on them.

The federal government may use several strategies when granting aid to states. First, timing and triggering approach specifically to ease effects of fiscal stress on local governments. The timing of this approach may differ from those targeting stimulation of the local economy.

Second, targeting approach focuses on specific areas hit hard by fiscal stress. The approach stimulates fiscal stress and promotes recovery of the local economy.

Third, there is also temporary strategy. The federal government uses this approach to prevent long-term dependence that may cause deficit in its national budget.

Fourth, there is also consistence approach to state aid. This ensures that the aid is consistent with the objectives of the federal government budget. The objective of this approach is to enable local government manage risks.

Consequently, it stops local governments from future expectations in cases of crises. This method also ensures that the local government maintains accountability as it also ensures that states have flexibility in spending. It also prevents states from “substituting their fund for federal funds” (Dilger, 2011).

Federal aid is rarely an option for states because of fiscal stress. However, states, which experienced severe effects of the 2008 recession, got aid from the federal government. In 2010, the Congress approved “$10 billion as aid for states to channel to education programs and create jobs” (Congressional Budget Office, 2010).

In 2008, states and local governments received “$6 billion for the Neighborhood Stabilization Program” (Congressional Budget Office, 2010). This program mainly focuses on areas experiencing foreclosures.

For instance, in the fiscal year 2010, the federal government gave $36.1 million grant to Michigan. This grant targeted the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS). This is because DHS is directly responsible for the US homeland security.

States usually get aid from the federal government based on the revenue they collect. As a result, states focus on increasing taxes in order to receive additional aid from the federal government. For instance, in 2010, Michigan did not collect enough tax to match $2 billion in federal highway aid for five years.

Consequently, Michigan proposed to increase per-gallon gas tax from 19 cent to 23 cents in 2011 and 27 cents in 2013.

Indirect support from the federal government goes to community programs. For instance, women and local farmers have received direct aid from the federal government to support their programs.

According to the US Census Bureau report of 2010, Michigan remains among the top beneficiary from the federal aid in selected programs (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

Responses of State governments to Fiscal Stress

Some of the responses state governments apply in response to fiscal stress included the following.

Cooperation and privatization

States have turned to intergovernmental cooperation for provisions of public services. This method has become widespread among municipal governments of various states. In addition, state governments have shown interests in expanding this form of cooperation.

State governments have also turned to “privatization or outsourcing of services in order to reduce costs” (Ivacko, Horner and Crawford, 2012). In the year 2011, a number of large states expressed their interests to increase privatization.

Fund balances

Some state authorities reported fund balances at the end of the fiscal year. Many states have indicated that they will utilize their balances to alleviate fiscal stress. Most local governments do not have any balance at the end of fiscal year. Thus, this is not an effective option for managing fiscal stress.

On this note, most state governments have also expressed their interests to use rainy day funds. However, most states have indicated that this is not possible in their current fiscal situations. This indicates that such state governments have exhausted their reserve limits.

Large states show highest rates of reliance on rainy day funds and fund balances than small states.

Health care costs

State governments have shifted rising costs of the health care to their employees in order to reduce fiscal stress. In fact, most local leaders view this as a viable strategy for the coming years.

Most state governments with fringe benefits have shown interests in reducing such costs so that employees can cater for them. For instance, 81 percent of large jurisdictions of Michigan have also expressed their interest to reduce such costs and benefits.

Reducing staff, services, and increasing fees

New employees who join state departments have received low pay than their existing counterparts in many states.

However, small states are not likely to hire new staff in the coming years. Thus, pay cut is the viable option for them. Most states and local authorities have also encouraged early retirement in order to reduce staff costs.

Summary

Fiscal stress across most of the US states increased sharply from 2000 to present. Fiscal stress became severe after 2008 due to effects the recession. As a result, Michigan has faced some of the largest fiscal gap in history.

However, alleviating fiscal stress in Michigan shall be difficult because of the aftermath of the recession and exhausted limits of rainy day reserves. In addition, the federal government does not want to grant aid to states because of fiscal stress.

Therefore, states like Michigan must find a balanced approach to reduce fiscal stress. A number of states have turned to increasing revenues and other cost reduction strategies.

Raising revenues and reducing spending can provide resources and save others during fiscal stress. Raising taxes can strengthen states’ tax sources. However, this may be a short-term approach, but states can use it to address long-term fiscal stress.

Conclusion

Recent studies have shown that Michigan fiscal stress has declined as there are improvements in many areas of fiscal stress indicators. Local authorities have expressed confidence that they are able to meet some challenges of fiscal stress than in the previous years.

This shows effects of approaches such as reducing costs, increasing revenues, and restructuring the budget to meet fiscal gap that Michigan used.

However, Michigan has reported mixed results. Large local authorities still have difficulties with their fiscal stress. Still, recent indications showing that the US economy has slowed down can negatively impact such gains made.

Recent changes in the State of Michigan fiscal budget and proposed tax increments can also drive other firms out of the state. On the other hand, any reduction in tax revenues can severely increase fiscal stress in Michigan. This implies that fiscal stress may persist for many years in the State of Michigan.

References

Congressional Budget Office. (2010). Fiscal Stress Faced by Local Governments. Washington, DC: CBO.

Dilger, R. (2011). State Government Fiscal Stress and Federal Assistance. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Feldman, N., Courant, P. and Drake, D. (2003). Michigan at the Millennium: The Property Tax in Michigan. Michigan: Michigan State University Press.

Finegold, K., Schardin, S. and Steinbach, R. (2003). How Are States Responding to Fiscal Stress? Urban Institute Program, 58, 1-8.

Ivacko, T., Horner, D. and Crawford, M. (2012). Fiscal stress continues for hundreds of Michigan jurisdictions, but conditions trend in positive direction overall. Michigan: The Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy.

Kloha, P., Weissert, C. and Kleine, R. (2005). Developing and Testing a Composite Model to Predict Local Fiscal Distress. Public Administration Review 65(3), 313- 323.

Levine, C. (1980). Managing Fiscal Stress: The Crisis in the Public Sector. Chatham, MA: Chatham House Publishers.

McNichol, L. (2003). The State Fiscal Crisis: Extent, Causes,and Responses. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Mouritzen, E. (1992). Managing Cities in Austerity, Urban Fiscal Stress in Ten Western Countries. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Pagano, M., Hoene, C. and McFarland, C. (2012). City Fiscal Conditions in 2012. Washington, DC: National League of Cities.

Reschovsky, A. (2004). The Impact of State Government Fiscal Crises On Local Governments and Schools. State and Local Government Review 36(2), 86-102.

Schick, A. (1980). Fiscal Stress and Public Policy: Budgeting Adaptations to Resource Scarcity. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Skidmore, M. and Scorsone, E. (2009). Causes and Consequences of Fiscal Stress in Michigan Municipalities. State Tax Analyst Report, 9, 675-692.

State of Michigan. (2011). Michigan: Fiscal Years 2012 and 2013 Executive Budget Recommendation. Michigan: Department of Technology, Management and Budget.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2011). Federal Aid to States for Fiscal Year 2010. New York: State Data Center.