Introduction

The term aesthetics conventionally means beauty or attractiveness. However, in the world of dentistry, aesthetics refers to the facade of a restoration (Darvell, 2013). Smile, on the other hand, is a key facial expression that often communicates an individual’s emotions. A smile can be described as an alteration in the facial expression that entails lightening of the eyes, a rising curving of the mouth angles without noise and a muscular deformation as that witnessed in a laugh (Duggal, 2012). This expression is used in the display of amusement, fondness, suppressed laughter, biting wit, contempt among other emotions. During social contact, most people tend to focus their interest to the face particularly the eyes and mouth of the person speaking (Oshagh, Moghadam & Dashlibrun, 2013). Consequently, the mouth plays a significant role in the pleasant appearance of an individual. For this reason, the mouth is referred to as the aesthetic zone (Van der Geld, Oosterveld & Kuijpers-Jagtman, 2008).

The key components of the aesthetic zone are the dimensions, form, arrangement, and colour of the teeth. In addition, the shape of the gingiva, the buccal passageway and the structure of the lips determine the overall appearance of the aesthetic zone. Smile and facial attractiveness go hand in hand and play a significant role in the self-esteem of an individual. Beautiful smiles enhance a feeling of confidence and youth (Oshagh, Moghadam & Dashlibrun, 2013). The types of motions made by the lips and teeth while talking or smiling determine the extent of the aesthetic zone (Van der Geld, Oosterveld & Kuijpers-Jagtman, 2008). Attributes such as the position of the lips when smiling and the amount of teeth on show are vital “diagnostic criteria in orthodontics, dentofacial surgery, and aesthetic dentistry” (Van der Geld, Oosterveld & Kuijpers-Jagtman, 2008, p. 366). Therefore, dental restorations aim to provide patients with almost perfect natural looks that closely resemble the original tissues in form, shade and flawlessness. This literature review covers the essential information that every dentist needs to know about the aesthetic zone and smile.

The Smile and its Proportions

Smile lopsidedness plays a vital part in the perception of beauty. From an anatomical stance, a smile is generated by the contraction of the muscles situated close to the eyes and buccal cavity. A smile can be categorised into three groups depending on the muscle involved and the direction of motion of the lips (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012). The involvement of all the levator labii superioris brings about the cuspid smile, which displays the teeth and gingival tissue. The complex smile, conversely, is typified by the involvement of levator labii superioris in addition to the lower lip depressors. In the Mona Lisa smile, the zygomatic major muscles raise the commissures and move them towards the outside then the top lip forms a curve. Figure 1 illustrates the three types of smile.

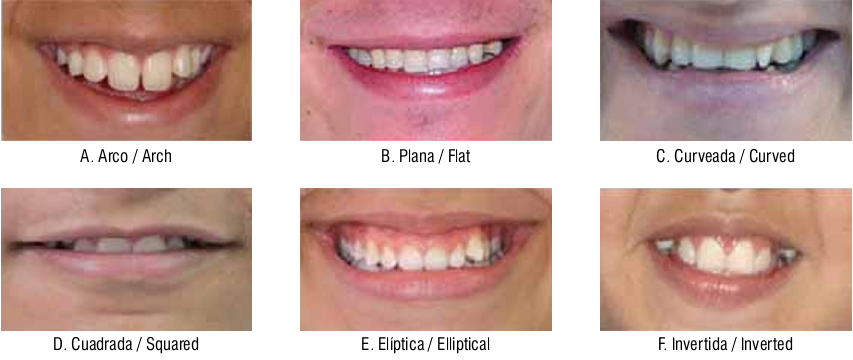

The smile can also be grouped into three depending on the degree of awareness involved. For example, the deliberate smile may or may not be inspired by a feeling while the static smile can be reproduced. The instinctive smile is inspired by genuine human emotions and cannot be prolonged. From an anatomical standpoint, the smile can be categorised according to the position of the gingival line as high, low or average. A perfect smile is determined by the proportion and stability of facial and dental traits such as colour, shape and arrangement of teeth. The judgement of a harmonic smile entails the evaluation of the smile zone whose shape may qualify its description as “straight, curved, elliptical, arched, rectangular, or inverted” (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012, p. 355). Figure 2 illustrates the various smile zones.

Another vital component of the smile is the smile arc, which is the relationship of the top edges of the incisors and the outline of the bottom lip while smiling. According to the relationship exhibited, the smile can be described as consonant, flat or reversed (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012). A number of standards have been used as reference pointers to determine if an individual has a harmonic smile or if the smile deviates from the expected. An aesthetic smile is determined by three main factors, which are the teeth, lips and gums (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012).

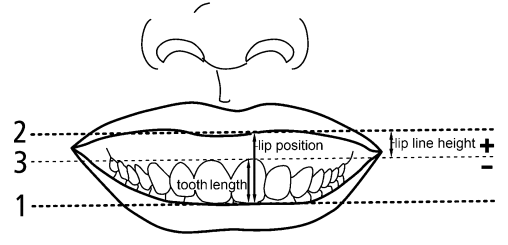

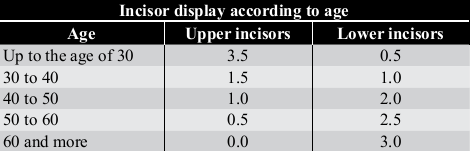

The lip facet entails the morphology, lengthwise measurement, breadth, size, proportion and thickness. For example, the length of the lips, which is measured as the expanse between the lip and the bottom of the nose, is supposed to be between 20 and 22 millimetres in young females, and between 22 and 24 millimetres in young men (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012). The length of incisor on show is supposed to be between 3 and 4 millimetres in females and between 1 and 2 millimetres in males. It is worth noting that the amount of teeth exposed at rest decreases with an increase in age due to muscular reduction and loss of lip volume that causes the lips to extend thereby covering more of the anterior teeth during smiling. Additionally, while smiling, the breadth of the lips ought to be at least half the width of the face. A symmetrical smile implies that both sides of the lips should have similar curvature hence be mirror images of each other.

The gum aspect entails the evaluation of four main parameters. First, the boundaries of the maxillary mid teeth should be even, whereas the edges of the lateral incisors should be 1 millimetre higher than the margins of the central teeth. The gingival border of the canines ought to have a similar level as the margin of the central incisors leading to the development of a seagull effect as illustrated in figure 3.

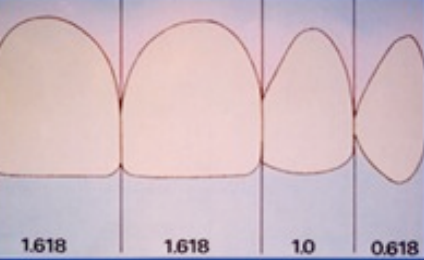

Secondly, the gingival apex, which is the innermost spot of the gingival tissues on the longitudinal axis, should correspond to the axis of the top sideways and mandibular incisors. The vestibular gingival border has to replicate the cemento-enamel intersection. In addition, the presence of papilla between the teeth brings about the most beautiful smile. Ultimately, the organization of teeth on the gums is also vital. The length, width, shape of teeth, and matrix ought to be in the right ratios. The typical length of the mid incisors and canines in males is 10 millimetres, whereas the average length is approximately 9 millimetres in females. The sideways incisors are, on average, 1.4 millimetres smaller than the mid incisors in the two sexes. The girth of the sideways incisors is approximately 66 percent of the breadth of the medial incisors (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012). The relationships of the sizes of the mid and sideways incisors are referred to as the “golden proportions” (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012; Duggal, 2012; Frese, Staehle, & Wolff, 2012). The shades of the teeth (dental matrix) are also supposed to be uniform for an aesthetic smile.

A comprehensive evaluation of a smile must take account of four facets namely the vertical, sagittal, oblique, and time aspects. The vertical element appraises the exposure of incisors with the lips at rest while the acuminous factor estimates the “overjet and angulation of incisors” (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012, p. 356). On the other hand, the oblique component examines the smile curve as well as the palatal plane direction, whereas the time aspect encompasses features such as development, maturation and growing old.

The Aesthetic Zone of Smile

The two main forms of smile are the “the enjoyment or Duchenne smile and the posed or social smile” (Duggal, 2012, p. 12). The posed smile is controlled and is not brought forth by a feeling. Therefore, it can be sustained. For this reason, it can be employed in orthodontic diagnostics and the development of therapy. The quantification of a smile entails purposive and biased assessment. Purposive evaluation of a smile denotes the objectives that need to be achieved at the conclusion of treatment, whereas biased assessment involves the personal preferences of the patient as well as the clinician. However, it must be noted that no universal idyllic smile exists and that the fundamental aesthetic objective in orthodontics is to produce a proportionate smile characterized by the proper placement of the scaffold and teeth in the dynamic display zone. The dynamic display zone takes in sideways, upright, anteroposterior facets of “the maxillary anterior transverse occlusal plane and the sagittal cant of the maxillary occlusal plane” (Duggal, 2012, p. 13). Designing a smile, therefore, must take into account the aesthetic plane of occlusion, which exhibits marked disparities from the natural plane of occlusion.

Bracket placement is the initial step in getting or sustaining a ‘consonant smile arc.’ The overall success of designing a smile relies on the causes of the dental problem, which determine the course of therapy.

Clinical Evaluation in the Determination of the Aesthetic Zone of Smile

The correct diagnosis is necessary for the correct treatment. All forms of diagnosis must be done with the patient sitting in the natural head position (NHP), which allows the patient to concentrate on a distant object at eye level. This position creates an extra-cranial vertical as well as parallel lines that are used as reference points (Duggal, 2012). The patient’s smile in addition to speech and oral pharyngeal performance is obtained using harmonized digital videography. Figure 5 illustrates the process of smile detection for a patient in sitting position.

The frames obtained from the video camera are then converted into JPEG files using video editing software and subsequently standardized using Adobe Photoshop CS2 as described by Desai et al. (Duggal, 2012). Clinical evaluations are then performed on the edited photos based on dento-facial analysis as well as dental analysis. Dental analysis includes tooth analysis, tooth and lip analysis and tooth and gingival analysis.

Dento-Facial Analysis

The dental midline ought to be in alignment with the midline of the face. However, this does not always happen and discrepancies within the range of 4 millimetres are considered the norm. Restorative dentistry can be used to rectify the problem of incorrect alignment of the midlines provided the maxillary centrals are balanced and the right connections between teeth are sustained. Orthodontic therapy is appropriate whenever a huge midline difference is present and the teeth do not require repair. It is also imperative to observe the soft tissue attachment that may be preventing the closure of the midline diastema as illustrated in figure 6.

Dental Analysis

Tooth analysis entails establishing the relationship between the teeth and the lips. Normal maxillary central incisors have a length of between 10 and 11 millimetres. For an aesthetic smile, this length ought to be between 10.5 and 12 mm. A length of 11 mm is the most appropriate during the beginning of the design process as it can be modified in the course of the treatment. The most beautiful smiles are produced by teeth whose width and length yield a ratio of 80%. The middle incisors are expected to exceed the length of the sideways incisors by 1 to 2.5 millimetres. On the other hand, the length of the mid incisors ought to surpass the length of the canines by between 0.5 and 1.8 millimetres.

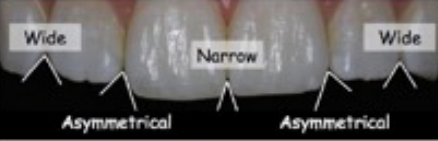

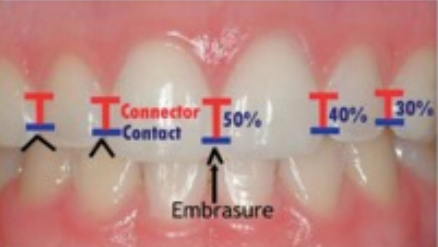

The appearance of tooth connectors, embrasures and contacts is also vital in planning for treatment. The interdental points of contact can be described as the precise position that the teeth get in touch with each other. The connector, in contrast, is the position where the incisors and canines seem to make contact. These connection lines increase at the tips as the teeth advance from the midpoint to the posterior. Similarly, the connecting lines increase from the mid incisors to the other teeth. The embrasures, which are the pointed spaces between contacts, also enlarge as the teeth advance posteriorly (Duggal, 2012). Figures 7 and 8 illustrate the contacts and embrasures. Sometimes these dimensions can be too wide or too narrow thereby interfering with the aesthetics of a smile.

Tooth Proportionality and the Golden Ratio

There is an intertooth association that ought to be sustained as an individual smiles for the smile to be considered aesthetically pleasing. The maxillary incisors ought to appear balanced and dominate a beautiful smile. The precise dominance of the maxillary incisors is what is referred to as the golden ratio. The golden ratio is defined by the apparent width of the lateral incisor being approximately 65% or two thirds of the apparent width of the central incisors (Duggal, 2012, p. 17). The canines, however, do not adhere to the golden ratio and are about three quarters of the width of the maxillary incisors in highly aesthetic smiles.

Tooth and Lip Analysis

Studies show that the average middle-aged woman displays about 3.5 millimetres of the maxillary incisors when the lips are at rest. However, dentists recommend that the denture should be set to expose a maximum of 2 millimetres at rest, which is even undesired in aesthetically driven patients who prefer between 3 and 4 millimetres exposure. A beautiful smile requires that the ends of the maxillary incisors almost touch the lower lip, but leave a maximum distance of 3 millimetres. Aesthetic recontouring and conservative restorative dentistry can be used to treat any slight digressions from the tooth patterns described. Restorative dentistry, however, is not advised in incidences with perfect tooth shape and tincture as it only produces mutilations to the healthy tooth structure. Such incidences can be remedied by orthodontics.

The Buccal Corridor

The buccal corridor is the expanse between the maxillary posterior teeth and the inner cheeks (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012). According to Bolivar and Mariaca, the buccal corridor is categorised as wide, a bit wide, medium, a bit narrow and narrow with a prevalence of 28%, 22%, 15%, 10% and 2% in that order (2012). This space is undesired in aesthetic smiles and may be caused by factors such as crosswise thinning of the maxilla, “palatal angulation of the maxillary posterior dentition and retro-positioned maxilla” (Duggal, 2012, p. 19). A wide smile with minimal buccal passageway is deemed attractive by laypeople. Therefore, this space needs to be considered during restorations.

Dental-Gingival Analysis

The lips determine the shape of a smile and the gingiva, which in turn shapes the teeth. There should be synchronization in the proportion of tooth form and the quantity of lips and gums displayed to inhibit one aspect from overshadowing the others. During dental-gingival analysis, the most important characteristics to be considered include the Morley ratio (the extent of the frontal maxillary incisor exposure), the cover of the top lip and gingival presentation (Duggal, 2012). In an aesthetic young-looking smile, three quarters to the entire maxillary main incisors ought to be on show at the bottom of an imaginary line sketched flanked by the commissures. Figures 14a and14b illustrate an acceptable Morley ratio and excessive display of incisors.

Additional aspects to look into in fabricating attractive gingival associations are the hue of the gingival tissue, curvature, the position of the papillary tip, and the gingival boundary. The curvature of the gingival boundary with the tooth is influenced by the cement-enamel junction and the osseous crest, which in turn affect the shape of the gingival. Figure 15 shows the ideal scalloping of the gingival.

The above-mentioned parameters are useful in the designing of a smile. When appropriately followed, these aspects help maintain the aesthetic zone of smile and enable a clinician produce results that are pleasing to the patient.

Fundamentals of Aesthetics

Creative flair is a prerequisite for the achievement of the highest level of cosmetic dentistry. A comprehension of the intricate relationship between artistic conjecture and clinical semblance enables the clinician to construct a smile or modify an imperfect display in a manner that is perceived as pleasant. The fundamentals of aesthetic care entail the influence of face-tooth interaction on aesthetics and how these attributes can be used to produce certain cosmetic effects (Singer, 1994). Singer argues that the increasing sophistication in aesthetic care makes the principles of aesthetics a necessary set of information for every dental clinician (1994). He goes ahead to explain the key aspects of aesthetic care.

A properly reinstated smile not only brings about a pleasant appearance, but also enhances periodontal health. Therefore, the overall outcome of a restoration needs to be functional and attractive. Previous studies insist on the influence of a perfect curvature on dental health. However, these studies do not illustrate how shape can be altered to attain the desired effect. Chalifoux as cited by Singer (1994) argues that the perception of teeth is the most important factor in aesthetics. He goes ahead to list some of the traits that interrelate to affect aesthetics. These factors include “colour, surface texture, position, tipping, rotation, occlusion, tooth size, lip structure, lip function, arch form, incisal edges, surface contours, line angles, contact placement, embrasure form, and gingival contour” (Singer 1994, p. 6). It is thought that perception holds more importance than the actual dimensions since what the patient sees is what matters most. However, perception is also an aspect of individual taste since different people view things differently. Therefore, it is important for any restoration work to meet the patient’s perception of attractiveness.

The culture under which one develops plays a substantial role in an individual’s perception of aesthetics. These perceptual biases can be categorized into two main groups namely cultural and artistic.

Cultural Biases

Cultural biases include factors such as age and gender. Teeth undergo significant changes following prolonged use and exposure to toxic substances. More often, the edges of teeth wear leading to a shorter and flatter appearance that is evidenced while smiling. The teeth appear even due to the destruction of surface texture. In addition, the colour darkens and the periodontium recedes leading to the exposure of gingival embrasures. In young people, on the other hand, the teeth have more surface texture and definite edges. The colour of the teeth is usually brighter and lighter due to limited exposure to harsh conditions.

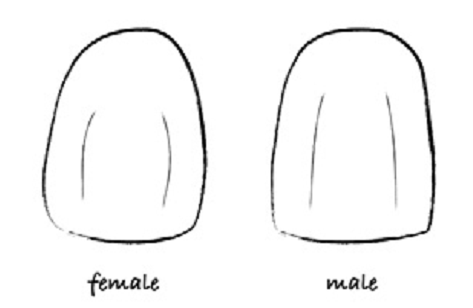

Studies on gender as a cultural bias reveal that women possess a higher smile line than men. It has been realized that the average woman has a smile line that is at least 1.5 millimetres more elevated than an average man due to a presumed shorter upper lip. In addition, the central incisor clinical crown is lengthened in men than in women leading to the development of stereotypes with smooth flowing curves being associated with females while hard chiselled angular lines are associated with masculinity (Singer, 1994). Genetic studies prove that there is no sexual dimorphism as far as the outline of teeth and smile lines are concerned. However, the society has a bias on the appearance of teeth and gender association despite the fact that there is no scientific evidence that links these traits to one’s gender.

Artistic Biases

Four artistic biases exist namely light, principle of illumination, principle of line, and the law of the face (Singer, 1994). The curving of teeth creates shadows and the illusion of shape. Therefore, light is of utmost importance in the visualization of shadows. In the principle of illumination, it is presumed that light moves forward as darkness recedes. This principle implies that objects with a brighter colour appear larger than dark-coloured objects. It is imperative for a cosmetic dentist to be knowledgeable of this notion when handling teeth as well as cosmetics. The principle of line has the implication that horizontal lines produce a semblance of breadth while perpendicular lines create a false impression of length. A cosmetic dentist ought to manipulate these effects to design restorative aesthetic effects.

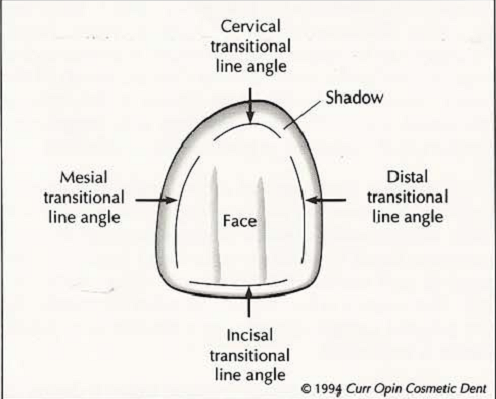

Conversely, the law of the face is the most crucial concept during the shaping of dental restorations. This law describes the aspect of the tooth that is seen by the observer as the apparent view. The apparent view consists of the face and the shadow. It is thought that two transitional line angles enclose the face of the tooth. The shadow, on the other hand, is the region outside the transitional lines. Figure 17 below illustrates the law of the face.

The shadow area is usually blocked by light from the face and appears to move away from the eyes. Therefore, the clinician can make disparate teeth look similar by ensuring that are their apparent faces are equal and that the regions of dissimilarity fade away in the shadow.

The Application of the Fundamentals of Aesthetics to Create Delusion

Manipulation of the perception of aesthetic display enables a clinician to employ the above-mentioned principles in creating the desired look. It is possible to use illusions to alter the shape, size and dimensions of the tooth. For example, a long tooth can be shortened by shifting the gingival and incisal transitional line angles towards the centre of the face thereby creating the effect of a shortened face. The incisal edge can also be slanted gingivally in the direction of the mesial aspect or midpoint of the notch. Increasing the length of the contact areas as well as reducing the girth of the gingival embrasures also augments the reduction in tooth length.

A short tooth can be made to appear longer by shifting the gingival transitional angle line in the direction of the gingival. The incisal transitional line angle is moved in the direction of the incisal edge. These procedures make the face appear longer. In addition, the placement of an opaque white stain line vertically via the incisal line and a white decalcified spot near the incisal edge also bring the illusion of a lengthened tooth.

Conversely, a wide tooth can be given a thin appearance by thinning the face, which is achieved by shifting the mesial and distal transitional lines thereby augmenting the area of the shadow.

Assessment of Various Aesthetic Smile Criteria

The field of dentistry has undergone a concept change from an emphasis on restoration to voluntary aesthetic therapy. Even though dental professionals are exposed to similar environmental styles and media outlook, educational encounters might create a preconception of a clinician’s artistic penchant that differs from those of the public. For these reasons, clinicians ought to comprehend beauty, accord, poise, and proportion as recognized by the public when setting up treatment. Various studies report that the opinions of dentists and laypeople concerning the beauty of a smile vary (Al-Johany, Alqahtani, Alqahtani, & Alzahrani, 2011). Levin (as cited by Frese, Staehle, & Wolff, 2012) reports that the most congruent frequent tooth-to-tooth ratio coincides with the golden proportion. However, a number of contradicting reports indicate that a large number of pleasant smiles do not have the golden proportion. Therefore, Al-Johany et al. assess the subsistence of various aesthetic smile measures on the smiles of celebrities chosen by laypeople to have the most beautiful smiles (2011).

Al-Johany et al. use the internet to obtain photographs of female superstars with the finest smiles in two specified years (2011). The pictures are analysed using the Digimizer image analysis software, which enables the evaluation of smile parameters. The parameters evaluated include the position and curve of the upper lip, the smile arc, the association between the maxillary front teeth and the bottom lip, the number of maxillary teeth displayed during smiling, the existence of the diastema, and midline evaluation. In addition, the smiles are evaluated for the existence of the golden proportion.

It is observed that most of the female celebrities possess most of the criteria for aesthetic smiles. However, the golden proportion is not evident in any of the candidates. In addition, the diastema is not present at the centre of the maxillary mid incisors in any of the candidates. These findings imply that the views of the laypeople regarding beautiful smiles are in agreement with those of dentists albeit with slight variations.

Self-Perception of Smile Attractiveness and its Influence on Personality

Facial good looks are key determinants of social associations as they affect various spheres of social life, for example, the success of relationships, assessment of personality, performance, as well as employment possibilities. Moreover, it is hypothesized that attractiveness has some bearing on social dealings and the development of character. Most attractive people tend to be self-confident and outgoing. A strong relationship exists between the beauty of a smile and facial attractiveness mainly because during social contact, an observer’s interest is targeted in the direction of the eyes and oral cavity of the orator. In addition, the mouth is the focal point of intercourse thereby making the smile a crucial determinant of facial looks and attractiveness.

Female attractiveness has been the centre of attention of art and culture in the past years. However, attractiveness is thought to affect an individual’s character irrespective of gender. Van der Geld, Oosterveld, Van Heck, and Kuijpers-Jagtman (2007) seek to ascertain that smile attractiveness is an aspect in bodily contentment that can affect personality traits in men as well. Van der Geld et al. engage 122 military men aged between 20 and 55 years in the study (2007). Images of the participants’ smiles are captured by digital videographic measurement. Each subject is then asked to fill a questionnaire on judgment of smile aesthetics as well as a personality evaluation test.

The participants judge smiles that expose most of the teeth as the most attractive. The tincture of teeth and conspicuousness of gums are considered important in the contentedness with the appearance of a smile. Moreover, the position and display of teeth show a strong relationship with dominance (Van der Geld et al., 2007). Van der Geld et al. conclude that size and visibility of teeth and the position of the top lip and are crucial features in self-perception of the beauty of a smile (2007). On the other hand, tooth colour and gingival show are important in individual satisfaction with the appearance of a smile. Smiles with unbalanced gingival exposure are deemed attractive and are associated with personality traits.

Various Perceptions of the Effect of Tooth and Gingival Display on Smile Attractiveness in Long and Short-Face Individuals

The evaluation of the attractiveness of a smile involves three key aspects namely the extent of gingival exposure, the curvature of the smile arch and the spaces within the buccal hall (Oshagh, Moghadam & Dashlibrun, 2013). Based on these criteria, smiles can be grouped into three main types, which are a high smile line, low smile line and an average smile line. In a high smile line, the maxillary incisors and the entire gingival line are exposed, whereas an average smile line reveals between three quarters and the full maxillary incisors. On the other hand, a low smile line is that which exposes less than three quarters of the maxillary incisors. It is thought that the raising of the upper lip up to the gingival borders of the maxillary incisors is perfect in a posed smile. Total concealment of the gingival is considered distasteful.

However, the judgment of beauty varies with individual taste and the social background, which changes from one person to another. It is, therefore, possible that professionals and laypeople’s view and expectations of aesthetics are varied. The heterogeneity in the physical attributes of people can bring about the categorization of facial types as long, short and normal. Ackerman, as cited by Oshagh, Moghadam and Dashlibrun (2013) hypothesizes that the outward appearance of beauty is influenced by the shape of the face. Short faces tend to amplify the crosswise facial disproportion and give the false impression of a flatter smile curvature and reduce the outward beauty of a smile. Conversely, a wide mouth passageway has the likelihood of drawing attention to the perpendicular facial disproportion and interfering with the outward beauty of a smile in an individual with a long face.

Oshagh, Moghadam and Dashlibrun (2013) are the first researchers to carry out a study that compares the influence of the incisor show on the aesthetics of the smile in various facial types. The perceptions are compared between dentists and laypersons. Four female patients with good-looking smiles, perfect dentition and well-arranged teeth are selected in this study. Five photos of each patient arranged in the order of increasing amount of gingival display (increments of 1.5 millimetres) are shown to sixty-two dentists and sixty-nine laypersons to rate the images.

It is realized that there are no substantial differences in the ratings given between male and female participants. The results of the laypeople reveal that in the patients with short faces, lower smile lines (1.5 millimetres coverage of the incisors) with minimal gingival exposure are more pleasant than high smile lines (Oshagh, Moghadam & Dashlibrun, 2013, p. 577). On the contrary, pictures with high smile lines (1.5 millimetres display of the gingival) receive higher scores than those with low smile lines in the long-faced patients. These observations are consistent with those obtained from dentists. Overall, smile lines consistent with the gingival margin are the best in both categories of participants. These findings are in agreement with Ackerman as cited by Oshagh, Moghadam and Dashlibrun (2013) that the outline of a face influences the overall attractiveness of a smile.

Smile Line and Periodontal Visibility

Apart from the shape, colour and position of the teeth, healthy and harmonious gingival is also important for an aesthetic youthful smile. The recent advancements in restoration procedures have made dentists even more aware of this fact. The position of the smile line is influential in governing the periodontal visibility. There is little information concerning the relationship between the visibility of the periodontium and teeth during smiling (Liebart et al., 2004). A previous study in 1980 by Crispin and Watson as cited by Liebart et al. reports that the gingival margin can be seen in 66% of 425 subjects during natural smiling (2004). Conversely, the gingival margin is seen in 84% of the participants during a forced smile. However, Crispin and Watson do not provide information for patients without an interproximal papilla even when the said loss is the key issue of concern. Liebart et al. observe that some studies report similar observations, but other studies only focus on the natural smile leaving out the forced smile (a study by Jensen et al. in 1999) while another study by Tjian et al. in 1984 does not specify the type of smile (2004). The following figures show the differences in the appearance of the smile line in the natural and forced smile.

When establishing periodontium visibility, a practitioner ought to check the marginal gingival visibility and that of the gingival membranes. It is also necessary to take into consideration the natural and forced smile before deciding on periodontal visibility. Therefore, Liebart et al. seek to determine the incidence of periodontium visibility in the natural and forced smile according to a novel categorization (2004).

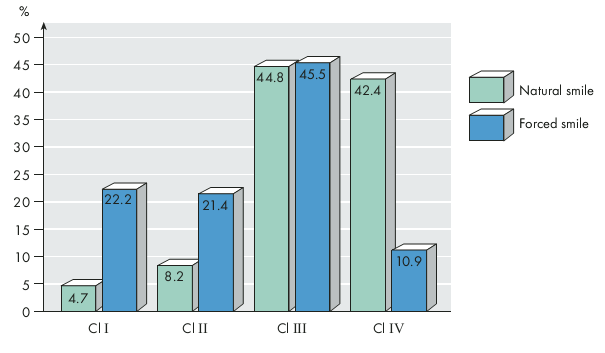

Five hundred and seventy-six (576) subjects between the age of 21 and 78 take part in the study. Out of these, 364 are females while 212 are males. All the participants have equal distribution of the anterior and posterior teeth between both sides of their jaws. All the subjects have healthy periodontium though a number of them have a healthy but reduced periodontium. Different pictures are taken of the natural and forced smile for each participant. A panel of seven examiners then examines the photos to determine the position of the smile.

The smiles are then analysed based on a four-group classification. The first category includes smiles where more than 2 millimetres of the marginal gingival can be seen or 2 millimetres apical to the cement-enamel boundary is seen in subjects with a healthy but diminished periodontium. This category is classified as ‘very high smile line’ (Liebart et al., 2004). The second category includes subjects with an exposure of between 0 and 2 millimetres of the marginal gingival (high smile line), whereas the third group included subjects with only the gingival embrasures visible (average smile line). The last category includes subjects with a low smile line where the gingival embrasures as well as the cement-enamel boundaries cannot be seen. The differences among the various groups are then determined statistically by Chi square test. It is shown that the majority of the study population falls under class 3. Figure 21 summarizes the outcomes of the study.

It is realized that 89.06 % of the study population expose their periodontium in natural and forced smile further showing that a pleasant smile involves the exposure of healthy gingival. The disturbance of the gingival contour due to depression, changed passive flare-up, or poor arrangement of teeth leads to an unattractive smile. In addition, it is realized that there is a substantial difference in the fraction of subjects who display their periodontium during the forced smile (90%) compared to 60% in the natural smile. These findings lay emphasis on the importance of examining the forced (maximal) smile during the evaluation of gingival visibility (Liebart et al., 2004).

A separate study by Passia, Blatz and Strub, analyses existing literature to determine the validity of the application of the smile line in evaluating a person’s smile (2011). The research looks at the aesthetic sense of orthodontists, the population and general practitioners. Approximately 309 articles published between 1973 and 2010 are examined out of which nine are selected according to the inclusion criteria. The included studies are all English publications that look at the smile line or smile arc as well as the assessment of the visual perceptions of people appraising the beauty of the smile.

Two thirds of the nine papers examine the association of the smile line with the top lip and the exposure of the front teeth of the upper jaw while smiling. Smile lines with three quarters to full display of the front top teeth are the most common with more than half of the study population having normal smile lines. Low smile lines are the least common. The following figures (22a to 22f) show the various smile lines as observed by Passia, Blatz and Strub (2011).

It is observed that high smile lines are more common in women than in men. In contrast, low smile lines occur more in men than in women. These results are duplicated when in a different research that looks at interracial patients. Another interesting finding by Desai et al. as cited by Passia, Blatz and Strub (2011) is that the smile line varies with age. Desai et al.’s findings show that the height of the smile line as well as the amount of anterior maxillary teeth exposed during smiling decrease with age (Passia, Blatz & Strub, 2011, p. 323). These findings are also echoed by Bolivar and Mariaca (2012).

The observations that there exist three major types of smile lines (low, high and average) and that these smile lines follow a pattern of distribution in the population implies that there is sufficient scientific evidence to conclude that a given smile line regularly occurs in the population. These findings are important during the repair of a patient’s intraoral situation. Another vital aspect that these findings give is that the choice of the appropriate smile line is determined by the age, gender and individual preferences of the patient. A larger quantity of front teeth display as a high smile line alongside an adjoining band of noticeable gingival is deemed more appropriate for a young female patient. A normal smile line with not more than three quarters of front teeth display and barely discernible gingival exposure, on the other hand, is thought to be ideal for an adult man. In addition, any oral rehabilitation procedure should strive to attain “parallel smile line, where the incisal edges of the maxillary anterior teeth follow the outline of the upper border of the lower lip during a smile” (Passia, Blatz & Strub, 2011, p. 325). An artistic clinician also tries to balance these features with the overall facial appearance of the patient. Therefore, to obtain an attractive and conventional treatment upshot, it may be necessary to combine various remedial measures such as orthodontics, surgery and prosthetic dentistry when planning a smile.

The Smile Line and Occlusion

Smile literature lacks evidence concerning the relationship of occlusal parameters such as angle molar categorization, the “anterior or posterior cross bite, overjet and overbite” with the smile line (Harati, Mostofi, Jalalian, & Rezvani, 2013). Harati et al. address this literature gap by establishing the influence of occlusal factors on the smile line (2013). The authors use 212 subjects aged between 20 and 30 without a history of orthodontic therapy or dental malformations. Natural smile images of the subjects are taken with a digital camera. Uniformity is obtained by requesting all patients to articulate a specified letter as the images are taken. Alginate depressions of the bows of the patients’ upper jaws are used to establish the type of curve. Intraoral assessment of the location of the lower first molar with respect to the top first molar is used to determine the angle of occlusal (Harati et al., 2013). The overbite is found by measuring the expanse between the incisal boundary of the bottom sideways incisors and a predetermined line is made. The overjet is also determined in the same way.

It is established that 72.2 percent of the population has a parallel smile line while 21.2% has a straight smile line. The remaining 6.6% has a reverse smile line. Statistical tests reveal a substantial relationship between the smile line and overbite. It is established that the majority of the patients with a deep bite have a parallel smile line. These findings imply that any inconsistency in the organization of the anterior teeth may distort the smile line. In the same way, damaged incisal facade of the front teeth is likely to lessen overbite and negatively affect smile aesthetics. Despite the association of the smile line and overbite, it is unclear whether a simple enhancement of the bite can restore a smile line. Therefore, there is a need for additional investigations to ascertain this supposition. It is also seen that the posterior cross bite has no association with the smile line (Harati et al., 2013).

The Influence of Age on Tooth Exposure and Lip Posture in Impulsive and Unnatural Smiling

Conventionally, photographs were used to obtain patients’ orthodontic records. However, novel videographic and computer technologies have made other diagnostics possible. The previous photographic methods made it possible to replicate the posed smiling, which is deemed unreliable since it is influenced by various factors such as a person’s social skilfulness and emotional upbringing. Therefore, a posed smile can be unnatural and unbalanced. It is thought that the spontaneous smile is the best for diagnostic purposes since it is an expression of an individual’s sincere emotions. Few studies examine the utilization of digital videography for creating measures to help in orthodontic diagnosis.

Van der Geld, Oosterveld, Berge, and Kuijpers-Jagtman (2008) examine the variations in the amount of tooth exposed, the vertical dimension of the lips, and the width of the smile among posed smiles and impulsive smiles. The authors use a digital videographic technique to capture the spontaneous smile at the precise moment it occurs with least patient intrusion. This objective is achieved by filming the partakers watching a comical movie. The subjects in the study are Caucasian males from three age groups (20 to 25, 25-40, and 50-55). In total, 122 participants are selected from approximately 1000 military personnel. The actual dimensions of the teeth and gingival tissues are obtained from evidence of complete denture.

It is observed that top lip-line crests in unprompted smiling are greater than in unnatural smiles. In addition, the amount of maxillary front teeth exposed decreases significantly from spontaneous smiles to posed smiles. It is also evident that the lips conceal the mandibular teeth during posed smiling compared to spontaneous smiling. These findings show that videographic techniques enable the reproduction of the spontaneous smile for accurate diagnostics. Additionally, the method offers adequate information regarding the heights of lip lines, which is vital in providing aesthetically pleasing outcomes in orthodontic and restorative treatments (Van der Geld, Oosterveld, Berge, & Kuijpers-Jagtman, 2008).

As a follow-up study, Van der Geld, Oosterveld and Kuijpers-Jagtman (2008), investigate the influence of age on the height of the lip line during smiling, speech and rest. The authors also aim to find out whether the lip height and tooth display adhere to a uniform pattern through these functions. It is revealed that during speech, the height of the upper lip is substantially lower than during unprompted smiling. Throughout unprompted smiling and speech, the bottom lip crest is stationed on the tooth. The bottom lip, therefore, hides the cervical gingival boundary. As a result, the lower teeth are exposed more during speech than in unprompted smiling.

There is a substantial relationship between the top lip line crests in unprompted smiling and tooth exposure during relaxation. The outcomes of this investigation are in agreement with previous studies that the vertical lengths of lip lines reduce substantially as individuals age (Van der Geld, Oosterveld & Kuijpers-Jagtman, 2008). The analyses reveal that significant alterations take place between the ages of 20 and 25 and between 50 and 55. Speech leads to a considerable appearance of the effects of age on lip line height especially in the maxillary front region since these differences are observed in all three age cohorts. The length of the upper lip at rest and in natural smiling is also found to increase with age in all three age categories.

The consistency in lip line heights all through impulsive smiling, talking, and tooth exposure at rest position implies that a uniform orthodontic stratagem is required in the three functional situations (Van der Geld, Oosterveld, & Kuijpers-Jagtman, 2008). Therefore, the major decline in maxillary lip line heights with age must be looked into in planning orthodontic therapy.

The contentment with oral looks is determined by sex and age (Van der Geld, Oosterveld, Berge, & Kuijpers-Jagtman, 2008). It is noted that the smile line reduces with the advancement in age due to an increase in facial height that leads to alterations in the dimensions of the upper lip (Van der Geld et al., 2008). Another possible explanation is that ageing distorts the elasticity of connective tissue, which causes the slumping of facial muscles (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012).

The study by Lierbart et al. (2004) confirms these findings for the natural smile, but not for the maximal smile. Previous studies report that women present higher smile lines than men. Liebart et al. note that men and women between the ages of 21 and 35 present high smile lines for the forced smile alone (2004). A systematic review carried out later by Passia, Blatz and Strub (2011) shows that more women than men tend to have high smile lines. However, in other instances there are no significant differences in the smile lines of men and women implying that age and gender do not affect the forced smile because of the spreading out of the lips during a forced smile.

The Relationship between Gender and Anterior Tooth Appearance

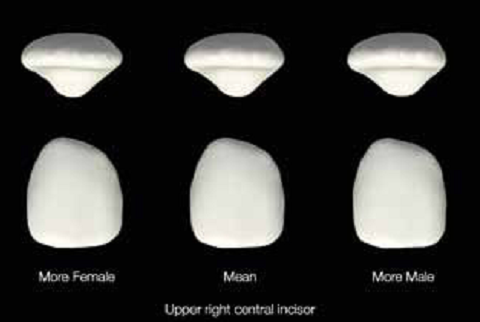

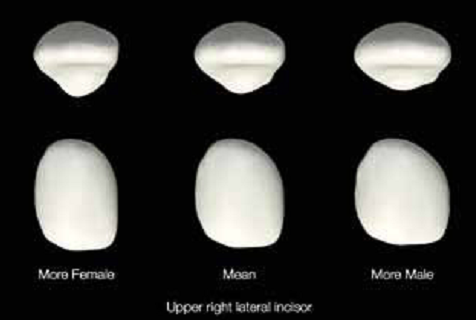

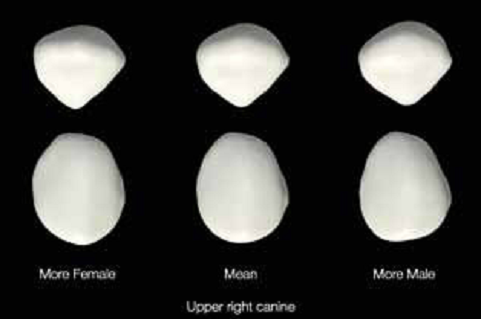

The beauty of the front teeth greatly influences an individual’s confidence as well as how other people perceive the individual. For this reason, beautiful outcomes are the objectives of dental therapy. The structure of the tooth and the adjacent soft tissues determine the beauty of a smile. Intact tissue can be utilized as guides when only a fraction of the dentition requires restoration. Nevertheless, in incidences where the whole dentition needs restoration and information regarding natural teeth is unavailable, pictures of the original structure or other methods can be used. The form of the maxillary front teeth is of utmost importance. Frush and Fisher, as cited by Horvath, Wegstein, Luthi, and Blatz (2012) presented the ‘dentogenic theory,’ which states that the appropriate shape of the anterior teeth ought to be chosen according to the sex, age and character of the patient. Frush and fisher suggest that womanliness is typified by roundedness, silkiness and gentleness giving rise to an oval tooth shape with curved borders (Horvath et al., 2012). On the other hand, masculinity is set apart by vivacity, bravado and solidity. Therefore, male teeth ought to have a cubical outline. Figure 24 illustrates the differences in shape between male and female teeth.

However, scientific investigations on the topic of gender and tooth form yield varying outcomes because of different methods of analysis. For example, in a study by Berksun et al. and Wolfart et al., there is no relationship between gender and shape of the front teeth when intraoral teeth independent of tooth size are evaluated (Horvath et al., 2012). A separate investigation that takes the volume of teeth into consideration reveals that men have bulkier teeth compared to women. Horvath et al. seek to ascertain the relationship between tooth shapes and sex using three-dimensional data to capture all aspects of the teeth.

Polyvinylsiloxane depressions of teeth from sixty male and sixty female Caucasian subjects aged between 18 and 30 years are made and poured in type IV dental stone. The depressions consist of the region “between the maxillary right first premolar” (Horvath et al., 2012, p. 337). Three-dimensional scans of the casts are made leading to the generation of approximately 21,000 data points. The matching points in all samples are then identified and evaluated against a set reference.

Horvath et al. realize that sex-specific disparities in tooth form and size indeed exist. These disparities were more evident in the maxillary right lateral incisor as well as the maxillary right canine. However, the maxillary right central incisor exhibits the least similarities between gender and tooth form. Figures 25a to 25c illustrate these differences.

The differences in tooth shape are vital for clinicians for the selection and application of the right tooth forms during front dental reinstatement thereby elevating the chances of success of therapy. In addition, these outcomes facilitate the virtual fabrication procedure with contemporary computer-assisted manufacture techniques (Horvath et al., 2012).

Another gender-related study looks at the influence of gender on the display of teeth and gingiva in the front area at rest and when smiling (Al-Habahbeh, Al-Shammout, Al-Jabra, & Al-Omari, 2009). The overall appearance of the face has sparked an immense fascination in modern prosthodontic therapy. The extent of front tooth exposure during smiling and when the teeth are at rest is a significant aesthetic aspect in shaping the result of restorative therapy. The dentofacial make-up includes the anterior and edged faces in the stationary and progressive states of the muscles. The location of the muscles guides the amount of tooth exposure at rest while a smile is decided by the position of the lips during motion.

The stationary position is brought about by the slight parting of the lips and shifting of teeth away from the occlusal plane. In addition, the peri-oral muscles are often in a state of relative repose. In this state, the display of teeth is determined by four features namely “lip length, age, race and sex (LARS)” (Al-Habahbeh et al., 2009). It is known that people with short top lips reveal a large portion of the maxillary central incisors compared to persons with longer top lips. Age is also thought to play a role in the volume of tooth visibility. For instance, the extent of maxillary teeth exposed decreases with an increase in age. Conversely, the volume of mandibular teeth displayed increases as one advances in age. Growing old lessens the tone of the orofacial muscles and softness of the tegumental relief in the bottom third of the face. These happenings lead to the formation of grooves and ridges around the nose and lips. Therefore, the upper lip loses flexibility and there is an increased tooth prop up by the gingival thereby reducing the amount of maxillary teeth exposure while increasing the mandibular teeth display (Al-Habahbeh et al., 2009). When examining different races, it is clear that Caucasians display more teeth than Blacks do. Larger upper lips in males cause them to show more than half of the front teeth during relaxation. Therefore, it is imperative for patients to be evaluated in accordance with the LARS aspect prior to the prescription of the amount of tooth exposure at rest.

The smile denotes the progressive aspect of dental-facial constitution. The magnitude of teeth displayed during smiling is determined by the bone structure, the extent of tightening of facial muscles and the dimensions of the teeth and lips. According to Al-Habahbeh et al. (2009), the location of the top and bottom lips as well as their motion. The authors point out that more females than males display more of the gingival tissue and that the gummy smile is more common in women than in men (Al-Habahbeh et al., 2009).

Al-Habahbeh et al. examine 247 Jordanian patients out of which 144 are females and 103 are males (2009). The patients are between the ages of 18 and 67, and none of them has undergone any orthodontic therapy. An electronic calliper with an electronic brain is employed in obtaining the dimensions. It is realized that the mean crown length of the mandibular and the maxillary teeth are higher in males than in females. In addition, males show “more of the maxillary lateral incisor, canine, and mandibular anterior teeth than the females” during resting (Al-Habahbeh et al., 2009). Conversely, females display more of the maxillary mid incisors than males although the differences do not show statistical significance.

It is shown that females reveal more maxillary front teeth than men do during smiling. In contrast, males reveal more mandibular front teeth and the related gingival tissues than females. These findings correspond with earlier research on the same issue. Therefore, the authors conclude that clinicians ought to take these findings during restorations to ensure that the outcomes of the treatments conform to the norm.

The Most Favourable Smile Line Aesthetics for Edentulous and Dentate Patients

Passia, Blatz and Strub (2011) have concluded that the smile line is an acceptable parameter for the evaluation of the beauty of a smile. Therefore, all patients exhibiting various dental conditions must be provided with the most appropriate smile line during restoration. Priest (2012) focuses on ways of ensuring that edentulous and dentate patients also achieve appropriate smile lines. A consonant smile line can be described as a smile line where the incisal ends of the maxillary front teeth correspond to the top boundary of the bottom lip border of the lower lip (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012; Passia, Blatz & Strub, 2011; Priest, 2012). A consonant smile line is a requirement for all patients including edentulous and dentate patients. The best smile is mainly determined by the angle of the occlusal plane, which can be adjusted using prosthetic, orthodontic or restorative therapy (Priest, 2012).

Smile Line Parameters and Correction Methods for Edentulous Patients

The most attractive positioning of teeth is determined by the central incisors (Frush and Fisher as cited by Priest, 2012). The canines ought to stand out from the lateral incisors to complete the required curve of the smile line. An occlusion rim is used to ascertain the location of the incisal ends through the assessment of verbal communication, support of the lips and aesthetics.

Thereafter, anatomical pointers, for example, the retromolar pad and comparative parallelism of the ridges are employed in the determination of the position of the rear teeth. The association between the front and rear pointers sets up the occlusal plane.

When viewing the patient from the front, the smile line formed by the front maxillary teeth ought to have the appearance of an outward curve that advances distally and moves in the same direction as the top boundary of the bottom lip. Figure 28a to 28c show the appearance of the smile line at various angles of the occlusal plane.

The thickness of the dental curvature also affects the outline of the smile line, but to a small extent. A wider arch seems to appear even when viewed at a given angle of the occlusal plane. In contrast, a contracted arc seems to appear more rounded when viewed at the same angle. Ultimately, the perpendicular location of each tooth affects the smile line, for example, elongating the maxillary mid incisors has the effect of highlighting the downward arc (Priest, 2012). For these reasons, the harmony of the smile line in edentulous patients can be enhanced best through the modification of the antero-posterior angle of the occlusal plane.

The sagittal orientation of the occlusal plane in edentulous patients can be determined by two landmarks namely “the Frankfort horizontal plane, which is the line between the auditory meatus and orbitale, and Camper plane, which connects the auditory meatus and the ala of the nose” (Priest, 2012, p. 192). A study by Batwa et al. as cited by Priest (2012) reveals that smiles with occlusal plane angles ranging from 5 to 15 degrees are considered more attractive than a smile with zero-degrees angle. This revelation alongside the Camper and Frankfort planes help clinicians to obtain an aesthetically pleasing occlusal plane (Bolivar & Mariaca, 2012). In addition, the utilization of the smile line as the critical guide to the direction of the occlusal plane enables the adjustment of the plane until the occlusal rim and the bottom lip become parallel. The position and direction of the maxillary occlusion rim need to be observed for harmony during smiling when the jaw-association data is being taken. Obtaining a consonant smile is a confirmation that the occlusal plane has been set up accurately.

Intraoral inspection of the mandibular occlusion rim, as well as the display of teeth, can also ascertain the precision of the occlusal plane. With the mouth open, the mandibular rim arc ought to match the bottom lip line. The final attempt to establish the occlusal plane when nothing else works out is moving individual teeth vertically (Priest, 2012).

Smile Line Parameters and Correction Methods for Dentate Patients

Substantial changes to the smile line in patients with undamaged dentition are deemed excessively destructive. For this reason, orthodontic treatment is thought to be the most appropriate corrective measure in dentate patients. A study by Ackerman and Ackerman proposes that orthodontics elevates the maxillary occlusal angle with respect to the Frankfort horizontal plane, which in turn enhances the consonance of the smile (Priest, 2012). Then again, some instances of orthodontic therapy yield unattractive smiles because of the flattening of the smile curve. In addition, orthodontic therapy has an undesirable outcome on the connection between the lip line and the smile in a third of the population under study. For these reasons, utmost care is required by clinicians to prevent the formation of a reverse smile. A different investigation reveals that changing the curve breadth influences the association of the top lip and the gingival boundary of the maxillary incisors. A possible solution to this problem is to avoid drastic alterations to the patient’s primary curve shape. Therefore, orthodontic treatment, just like any other corrective measure must strive to produce and sustain a consonant smile line.

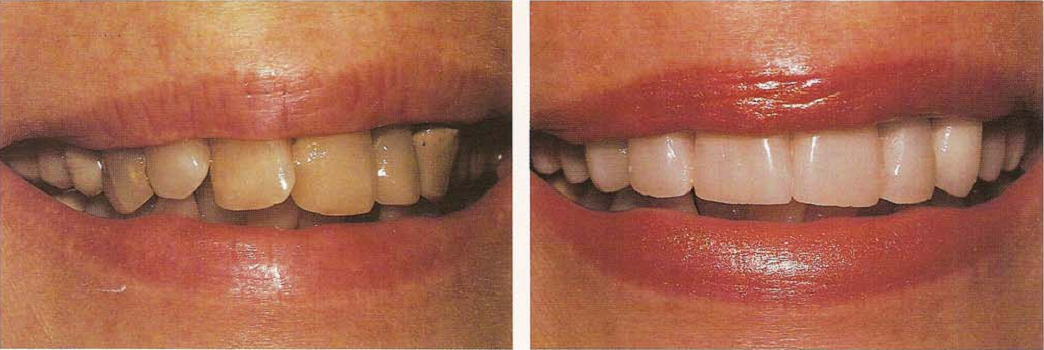

The use of veneers, crowns and fixed dental prostheses is a good substitute for orthodontics especially if the teeth require restoration. The location of the incisal ends is the preliminary stage and the most important factor in creating a consonant smile in dentate patients. A periodontal probe or a ruler calibrated to millimetres can be used to find the precise position of the incisal rim of the maxillary mid incisors with respect to the top lip. In some instances, patient may exhibit unpleasant reverse smile lines caused by excessively short front teeth because of wear or erosion and have up to standard occlusal planes. In such cases, lengthening the anterior teeth to the occlusal plane reinstates the smile line thereby improving occlusion by bringing about standard anterior pairing and guidance. Figures 29a to 29c show how the smile line is reinstated by teeth elongation.

The falling of teeth under the occlusal plane leads to an overstated curve. Veneers or crowns can be employed in shortening the teeth and enhancing the smile line by minimising the perpendicular overlap. These findings imply that the ideal tooth length is a prerequisite in achieving a consonant smile in dentate patients.

Changing the Position of the Lips during Enhancement of Smile

An aesthetically pleasant smile is a function of a healthy gingival, a comparative amount of gingival display during smiling as well as synchronization in the dimension, outline, arrangement and colour of the teeth (Ashtaputre & Rathi, 2012). The disproportionate exposure of the gingival leads to what can be expressed as a gummy smile, which is the chief source of awkwardness among patients. In such a smile, the gingival is the predominant feature that overshadows the lips and the teeth. A normal smile may lead to the exposure of the gingival to some extent in approximately half of the patients. However, an inflated smile reveals the gingival in three quarters of patients. A normal smile exposes the gingival between the lower boundary of the upper lip and the gingival margin of the mid incisors by between 1 and 2 millimetres (Ashtaputre & Rathi, 2012). In contrast, a gummy smile reveals up to 4 millimetres of the gingival.

Such problems can be rectified through surgery. However, it is important for a clinician to ascertain the cause of the excessive exposure prior to commencing treatment. Causes such as overdue eruption, poor alignment of teeth, a diminutive upper lip or bone irregularities are treated effectively by the lengthening of the crown, orthodontics as well as orthognathic surgery. However, patients with excessive mobility of lips leading to unwanted exposure of the lips can be treated by performing a lip-repositioning surgery. Lip-repositioning surgery is preferred in patients whose excessive gingival display is not a consequence of skeletal deformities. Such exposure should not surpass 7 millimetres. The procedure is contraindicated in grave perpendicular maxillary excess and insufficient connected gingival in the maxillary front portion. Other contraindications are similar to those of conventional periodontal surgery. Complications that may arise following the procedure include intermittent bruising following the surgical procedure, pain, paresthesia, transient loss of sensation and inflammation of the top lip. In addition, mucoceles can also form after the procedure.

In a case study by Ashtaputre and Rathi (2012), lip-repositioning surgery is performed on a 28-year old female who has a gummy smile as well as a thin upper lip. The gingival display is between 5 and 6 millimetres. The patient is informed of the benefits and possible complications of the surgical procedure. The proportion of the “buccolingual width to the cervico-incisal height” is obtained for each tooth (Ashtaputre & Rathi, 2012, p. 164). It is realized that an increase in the cervicoincisal height by between 1 and 2 millimetres is required for some of the teeth. Therefore, gingivoplasty is performed to attain the desired height to width ration for each tooth before lip surgery.

Seven days after the gingivoplasty, lip-repositioning surgery is performed under local anaesthesia. Two coextending cuts are made at the intersection of the mucosa and gingival junction as well as the mucosa of the labia. The two incisions are then joined at each initial molar leading to the formation of a curved shape. Thereafter, a thin layer of epithelial tissue is removed within the preformed outline. Intermittent stabilization stitches are then made on the coextensive cuts at the midline and the edges of the dissections to make certain that the midlines of the teeth and lips are well coordinated. Thereafter, a continuous interlocking stitch is used to secure both ends of the flap. Ibuprofen 600 mg and amoxicillin 500 mg are then administered for four and five days respectively to manage pain and prevent bacterial infection. The patient is advised to use icepacks and minimize smiling for at least one week. Figures 21 to 23 show the appearance of the patient’s smile before surgery, fourteen days later and six months thereafter.

The healing process is reported to have taken place without any eventful occurrence. The removal of the stitches after a fortnight leaves a scar that goes unnoticed because it is concealed within the mucosa of the upper lip. The study reports a reduction in the exposed gingival from 5 to 6 millimetres to between 1 and 2 millimetres after the surgical procedure (Ashtaputre & Rathi, 2012, p. 168). In addition, the height of the crown is increased to approximately 2 millimetres. The thickness of the upper lip also increases relative to the smile line leading to a more appealing smile. In addition, the patient is satisfied with the outcome of the surgery. This case study goes on to show that selecting the right candidate determines the success of lip-repositioning surgery in the correction of excessive exposure of the gingival during smiling. The authors conclude that lip-repositioning surgery is an effective and non-invasive method of restructuring a gummy smile.

Conclusion

Most of the studies agree that the smile line is an applicable instrument in the evaluation of the artistic manifestation of a smile. Clinicians and laypeople perceive the smile line in the same way. Therefore, the smile line can be used universally in the design of aesthetic smiles.

References

Al-Habahbeh, R., Al-Shammout, R., Al-Jabrah, O., & Al-Omari, F. (2009). The effect of gender on tooth and gingival display in the anterior region at rest and during smiling. The European Journal of Esthetic Dentistry, 4(4), 382-395.

Al-Johany, S. S., Alqahtani, A. S., Alqahtani, F. Y., & Alzahrani, A. H. (2011). Evaluation of different esthetic smile criteria. International Journal of Prosthodontics, 24(1), 64–70.

Ashtaputre, V. & Rathi, R. (2012). Smile enhancement by lip repositioning surgery: A case report. American Journal of Esthetic Dentistry, 2(3), 162–169.

Bolívar, M. A. L. & Mariaca, P. B. (2012). The smile and its dimensions. Revista Facultad de Odontologia Universidad de Antioquia, 23(2), 353-365.

Darvell, B. W. (2013). Esthetic dentistry. The American Journal of Esthetic Dentistry, 3(3), 167-168.

Duggal, S. (2012). The esthetic zone of smile. Virtual Journal of Orthodontics, 9(4), 10-22.

Frese, C., Staehle, H. J., & Wolff, D. (2012). The assessment of dentofacial esthetics in restorative dentistry: A review of the literature. JADA, 143(5), 461-446.

Harati, M., Mostofi, S. N., Jalalian, E., & Rezvan, G. (2013). Smile line and occlusion: An epidemiological study. Dental Research Journal, 10(6), 723-727.

Horvath, S. D., Wegstein, P. G., Luthi, M., & Blatz, M. B. (2012). The correlation between gender and anterior tooth form: A 3D analysis in humans. The European Journal of Esthetic Dentistry, 7(3), 334-343.

Liébart, M-F., Fouque-Deruelle, C., Santini, A., Dillier, F-L., Monnet-Corti, V., Glise, J. M., & Borghetti, A. (2004). Smile line and periodontium visibility. Periodontology, 1(1), 17-25.

Oshagh, M., Moghadam, T. B., & Dashlibrun, Y. N. (2013). Perceptions of laypersons and dentists regarding the effect of tooth and gingival display on smile attractiveness in long- and short-face individuals. The European Journal of Esthetic Dentistry, 8(4), 570-581.

Passia, N., Blatz, M., & Strub, J. R. (2011). Is the smile line a valid parameter for esthetic evaluation? A systematic literature review. The European Journal of Esthetic Dentistry, 6(3), 314-327.

Priest, G. (2012). Optimal smile line esthetics for edentulous and dentate patients. The American Journal of Esthetic dentistry 2(3), 188–198.

Singer, B. A. (1994). Principles of esthetics. Current Opinion on Cosmetic Dentistry, 1994(1994), 6-12.

Van der Geld, P., Oosterveld, P., & Kuijpers-Jagtman, A. M. (2008). Age-related changes of the dental aesthetic zone at rest and during spontaneous smiling and speech. European Journal of Orthodontics, 30(4), 366–373.

Van der Geld, P., Oosterveld, P., Berge, S. J., & Kuijpers-Jagtman, A. M. (2008). Tooth display and lip position during spontaneous and posed smiling in adults. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 66(4), 207-213.

Van der Geld, P., Oosterveld, P., Van Heck, G., & Kuijpers-Jagtman, A. M. (2007). Smile attractiveness: Self-perception and influence on personality. Angle Orthodontist, 77(5), 759-765.