Introduction

The key objective of this report is to describe the history of the Islamic capital market and this report focuses on the history of the Sukuk market, general principles of Sukuk, Secondary Market of Sukuk, the position of this bond in the global market particularly in Malaysia, Saudi Arabia and other countries of Gulf Cooperation Council. In addition, this paper concentrates more on the Structure of the Sukuk, financial and Legal challenges, growth of Sukuk in the stock market, present market condition of this product, and impact of the global financial crisis on the Islamic bond market and so on.

History of Sukuk

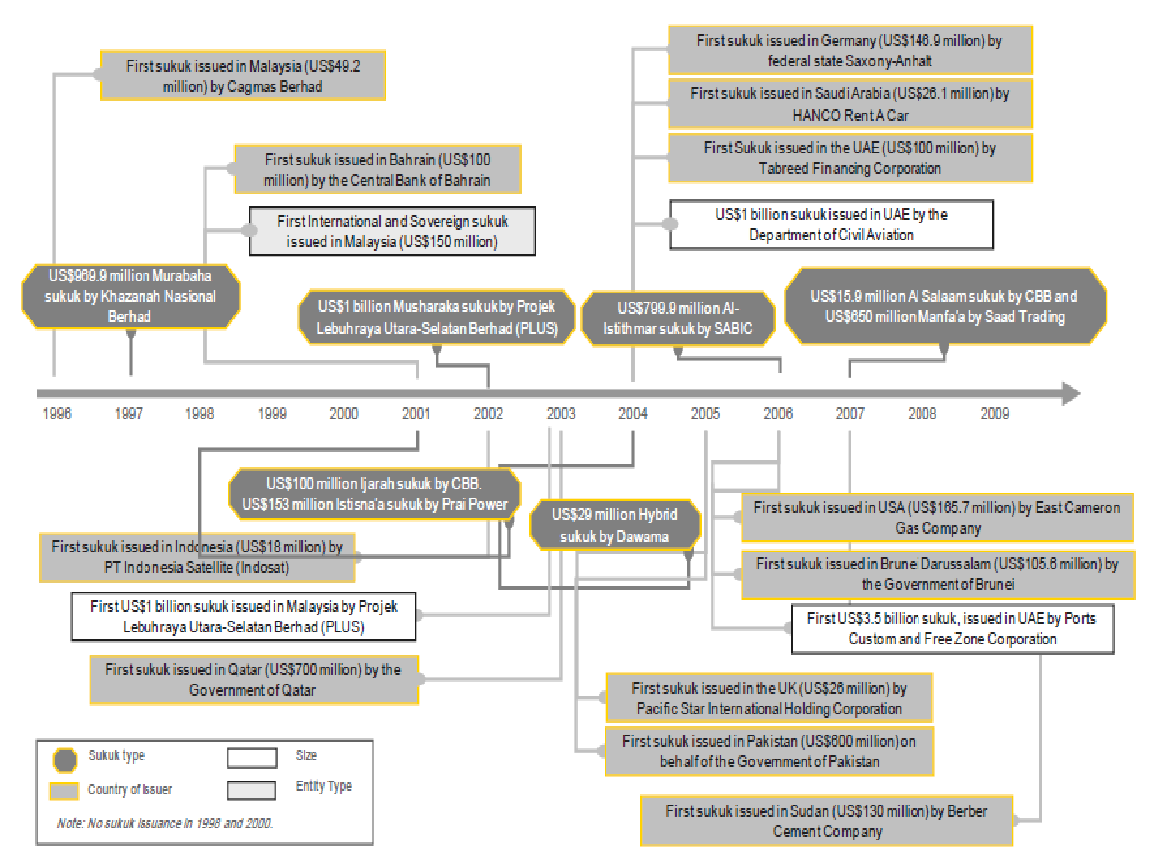

Ali (2010, p.1) stated that the people were unaware of the concept of Islamic capital market securities (Sukuk) market ten years ago and it was a new term to the customers through Sukuk was the common Arabic name and Malaysia started a sovereign Sukuk in 2002. Most interestingly, Chik (2009) stated that the history of the Islamic capital market can be found from the First Century and the Ottoman Empire issued esham in 1775 to overcome the problem related to the budget deficit. On the other hand, McNamara, Ijtehadi & Yasaar (2012) stated that the government of Malaysia claimed that they introduced a sovereign Sukuk way back in the fiscal year 1995 (the Malaysian National Mortgage Corporation issued the earliest Sukuk), which gained popularity in the mid-2000 due to saving the GCC members from the debt crisis.

Moreover, McNamara et al. (2012) further stated that Malaysia was the only active country in this industry before 1999; at the same time, Malaysia claimed that Bahrain joined in this sector in 2001 and the Central Bank of Bahrain was the foremost Sukuk issuer in GCC nations. However, Jobst, Kunzel, Mills and Sy (2008, p.5) argued that Sukuk has experienced huge success within a very short period due to the great demand to the corporate and public sector entities; in addition, Kettell (2008, p.4) said that Sukuk market is one of the fastest rising sectors of the Islamic finance industry due to providing several benefits to the customers. Ali (2010, p.1) expressed that Sukuk became popular from the very beginning because different influential factors helped to attract the customers, such as the meaning of this term is financial certificates (Islamic equivalent of bonds), but Islam does not permit interest-bearing bonds; in this context, Sukuk was one of the best solutions to the customer as it complied Islamic regulation. In addition, Jobst et al. (2008, p.5) stated that the Islamic capital market has expanded operation rapidly because Sukuk securities offer a number of products using competence and transparency of the capital markets to reach different types of customers in the GCC countries and rest of the world. On the other hand, many renowned researchers like Professor Nejatullah Siddiqui and Professor Volker Neinhaus have already criticized this concept in the modern Islamic perspective by stating that this bond has indeed developed as a torchbearer of Islamic capitalism; in addition, they stated that this bond provides little attention on the social responsibility issues. However, the following figure describes the history of Sukuk –

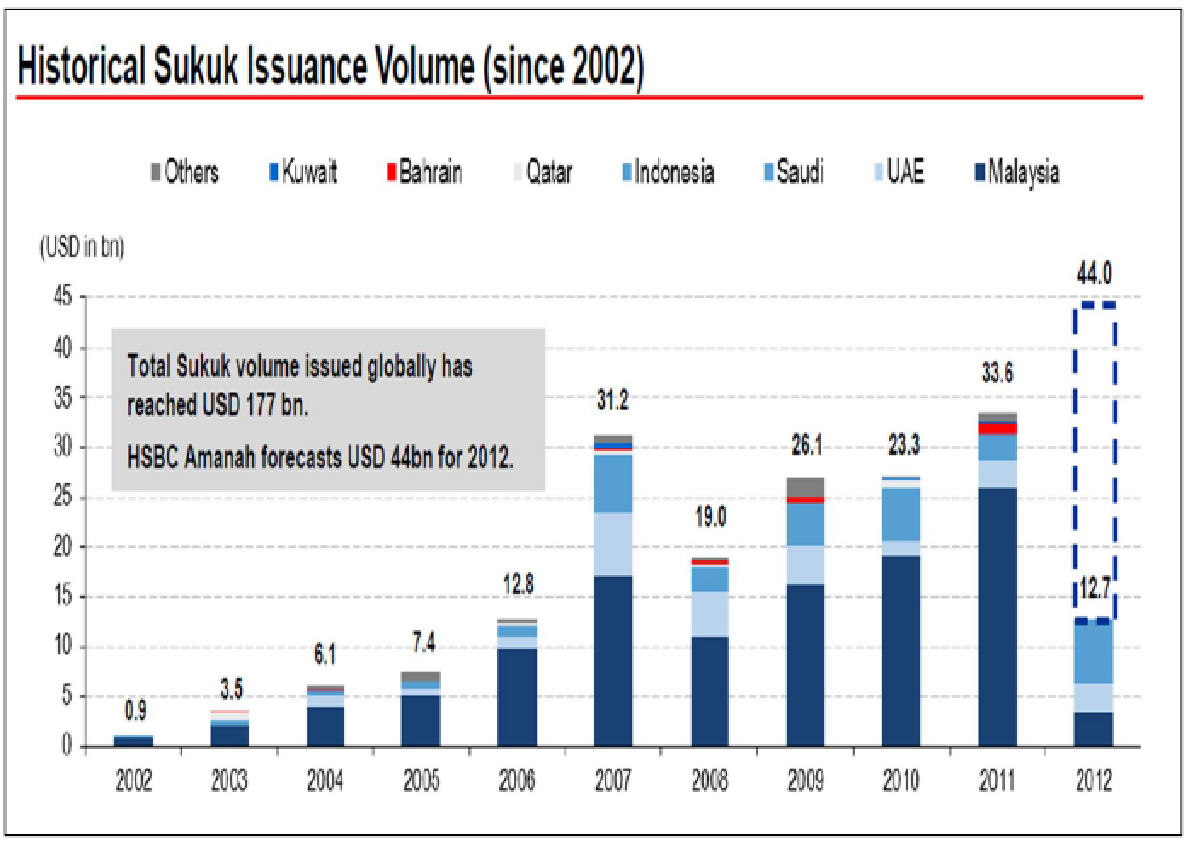

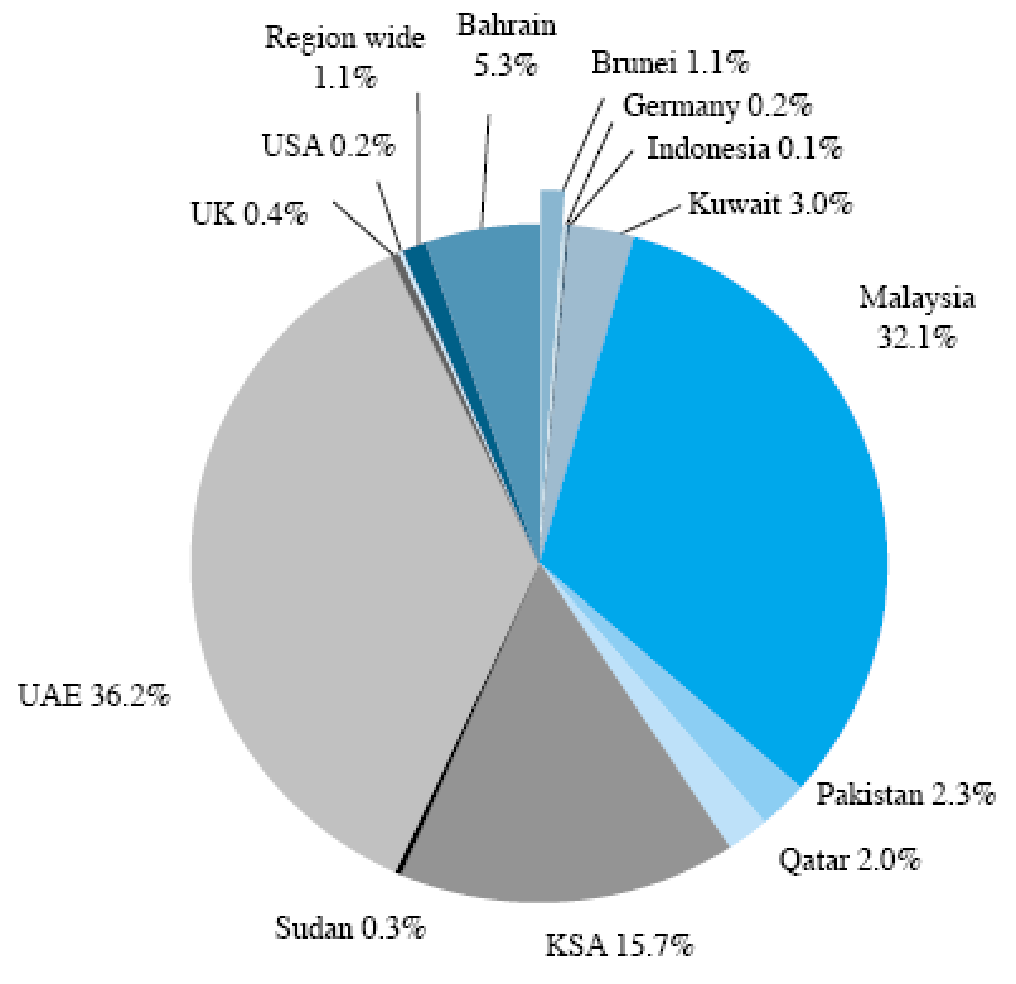

Rauf (2012, p.5) presumed that the total amount of Sukuk market would be $44 billion and Malaysia would lead this industry, but KSA and the UAE would significantly contribute the market, for instance, the market dropped in 2008 due to global financial crisis and sustained in the worst position for a long-time, but this industry recovered its position in 2012. However, the following figure shows that –

Principle of Sukuk

Bothra (2011, p.1) pointed out that the Principle of Sukuk has no determining difference with the conventional bonds, it is a new derivative Islamic finance that breed financial certificates with Islamic cover and the religion traders try to explore it as a Shariah-compliant financial instrument but its actually the old wine into the new bottle without any exception. Wan (2007, p.1) mentioned that although as a comparatively young asset class in the Islamic capital market Sukuk has generated tremendous success, there is huge criticism of this bond from the viewpoint of Muslim scholars who explained that its principles are against the Shariah law in the context of its structure and most controversial to the core values of Islam.

Kamali (2007) added that in the Quran at Surah At-Talaq, Ayah 6 and Surat An-Nisa’ [4:34] it has clearly mentioned to pay due to payment with kindness to workers for their labor and to clear the ‘wage’ to the women for their sexual contacts, but there is no indication to make any payment for Sukuk. Although the modern Islamic thinkers with leading schools of fiqh have been involved in legalizing Sukuk, the most prevailing literature of Islamic jurisprudence has been restricted to offering money for the monetary contract, especially in the mode of contemporary interest-based financing until it may qualify benefits and services in accordance with lawful benefit and service. The Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions has identified the attributes of Sukuk as a bond that sands with large area conflict and controversy that may face tremendous challenges for the global finance to uphold the Islamic moral standards of conducting business religiously where 85% of the existing Sukuks aren’t complying with Islamic law with principals as –

Although, the theoretician of Sukuk are trying to differentiate it with conventional bonds, the purpose and basic concept laid behind introducing Sukuk is to providing profits or revenues to the holder of the Sukuk in accordance with the share of the holder while that perverted theoretician would like to identify the same payment of conventional bonds by identifying them as Riba. Within the course of conventional bonds, the holder would get a debt certificate as a lender and gains earning on a fixed interest basis, while the same thing has misrepresented as ‘ownership shares of the assets’ where the Sukuk provides profit to the holder instead interest but do not provide any clear declaration regarding the loose sharing.

There is another initiative to differentiate Sukuk from the conventional bonds by arguing that due to the prohibition of Riba in Islam, the conventional bonds could not boom in the Muslim countries while Sukuk would be the best tools to play with the honest emotion of the religious-minded mass Muslims while profit hunter Muslim financial institutes don’t spare to cheat them. Under any circumstances, Sukuk has no attributes that could be different from conventional bonds with the exception of some Arabic names and terms, in both cases the investor earns more money than his investment for providing debts, no matter what the name, rather matter is that who pays money and for why. Money paid in exchange for debt financing must be treated as Riba, no matter what the profit hunter financial institutes named them at their brochure as Islam has strictly prohibited the debt financing and the great prophet Hazrat Muhammad (Peace be upon him) advised his followers for not to taking additional money for debts. He also advised his friends and surrounding to conduct the life with honest earning, be a magpie and economical for expenditure, and try to lead debts free life, for any emergence if someone takes debts, must be provided to assist his without any hope for addition return; on the other hand, who takes debt, must return that within the committed time.

The Shariah law explains that money functions to generate assets otherwise trade with assets, but itself may not consider an asset while Shariah has strictly banned trade to making money for money or trading the future profit or interest or riba, but the prevailing practice of Sukuk or conventional bonds have evidenced that the capital mobilization is the important issue. The Ambiguity in understanding Sukuk has been generated for the reason that there is no written legislation in Islam regarding this issue, but the modern literature of Islamic jurisprudence has been organized by the Muslim corporate bodies those who may bias the contributors to provide an explanation in favor of Sukuk. On the other hand, due to the lack of any regulatory bodies in the Muslim countries to manage and administer the Islamic law harmonization in accordance with the changing dynamics of life and technology that are restructuring with the needs of life, the Islamic financing needed to enough brave to encounter with traditional bonds through Sukuk without any religious coverage.

The study and practice of Fiqh is a very complicated area in Islam that need extraordinary scholar in the area of legal study, especially to provide any new verdict is required to know the modern human rights and theories of an open economy, but it has evidence that people with lower quality and less academic background are providing new verdict. Thus, the principles of Sukuk has organized with enough vagueness while the contributors of Sukuk are facing more than ever complaints that it has not complied with Shariah laws that may generate new complicacy due to variations of this financial product in banking and financial institutions of the Muslim countries and their existing practices within the financial industry.

Other principles of Sukuk are also like the conventional bonds and put on the market with a repurchasing accord to ensure guarantee to the borrower payback face value on maturity, in this character of Sukuk there is nothing new that can differentiate this Islamic financial instrument from the other traditional bonds. Meanwhile, there is no standardization authority globally that can unify the different Sukuks and would be guaranteed the acceptance of it to all other financial institutes in the purpose of selling of debts or receivables which are evidenced in the case of different Shariah boards prevailed in the market for long. On the other hand, Sukuk has withdrawn the provision of penalties for late payment and permitted delayed payment or redemption without facilitating any additional scope of earning that may throw the investors in great uncertainness, in the name of religious values Sukuk has generated further uncertainty with its contractual terms by creating hazards with ‘Maslahah’ that denotes public benefit.

Structures of the Sukuk

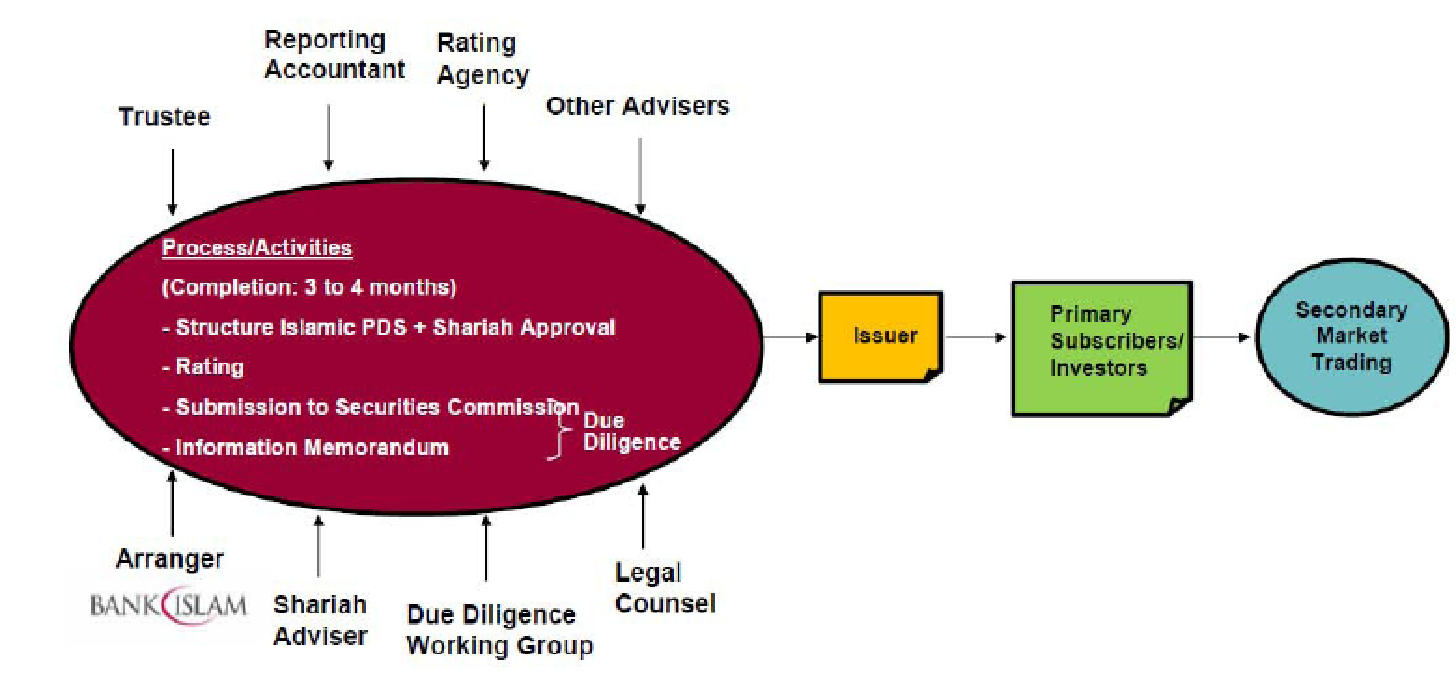

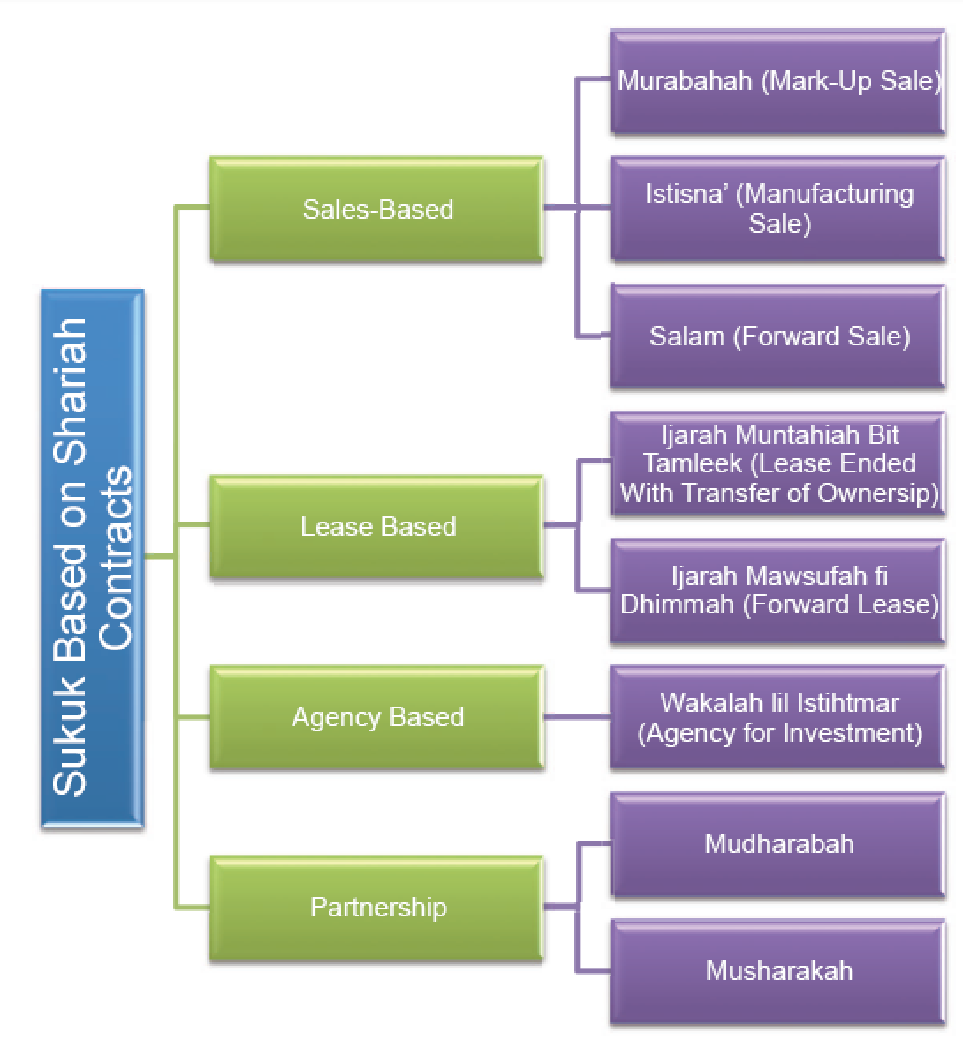

McNamara et al. (2012) stated that there is no specific structure, but it has different characteristics, which differentiate them from conventional bonds, such as product design along with offerings, and rating systems; at the same time, Chik (2009) said that determination of Sukuk based on the Shariah contract by which agreement made between the issuers and investors –

Chik (2009, p.11) provided most frequent classification considering Shariah contracts though each contract would have arisen different obligations; however, four classified types of Sukuk are presenting in the following graph –

Theoretically, there are four broad categories of Sukuk McNamara et al. (2012) and the general characteristics are different from each other; however, chronological developments, maturity stage, and ladder of sophistication are the main criteria of product differentiation, for example, following table discuss for broad categories briefly –

Table 1: – Four broad categories of Sukuk. Source: – Self generated from McNamara et al. (2012)

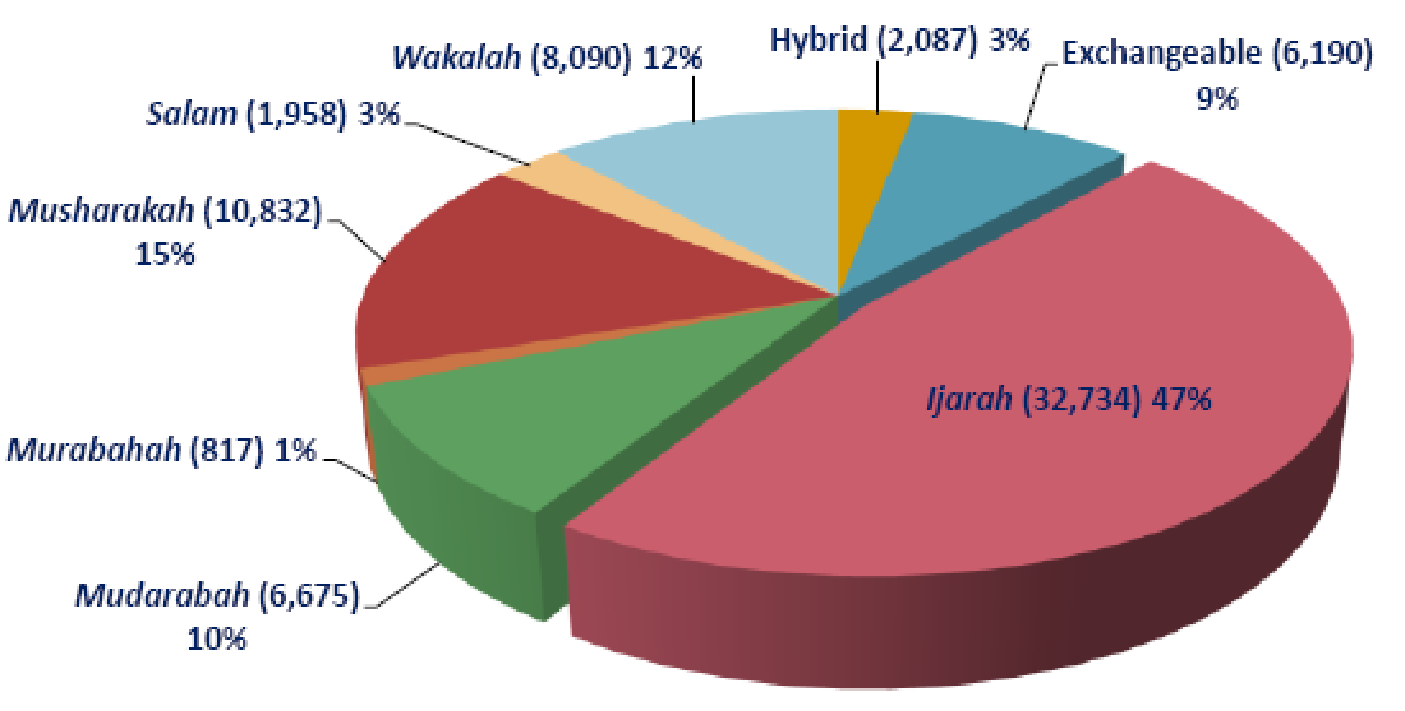

IIFM (2012) provided the data related with the breakdown of structure of international Sukuk from the very beginning in order to identify the trend of the issuers in the Islamic Capital market and the following figure shows that Sukuk Ijarah is the highest position in terms of issuance and attractiveness –

According to the view of Ali (2010, p.1) and Farah (2008), Sukuk considers numerous innovative Shariah compliant forms along with a variety of particles of Islamic forms; however, Islamic Financial Institutions provide 14 types of Sukuk –

Sukuk Ijarah

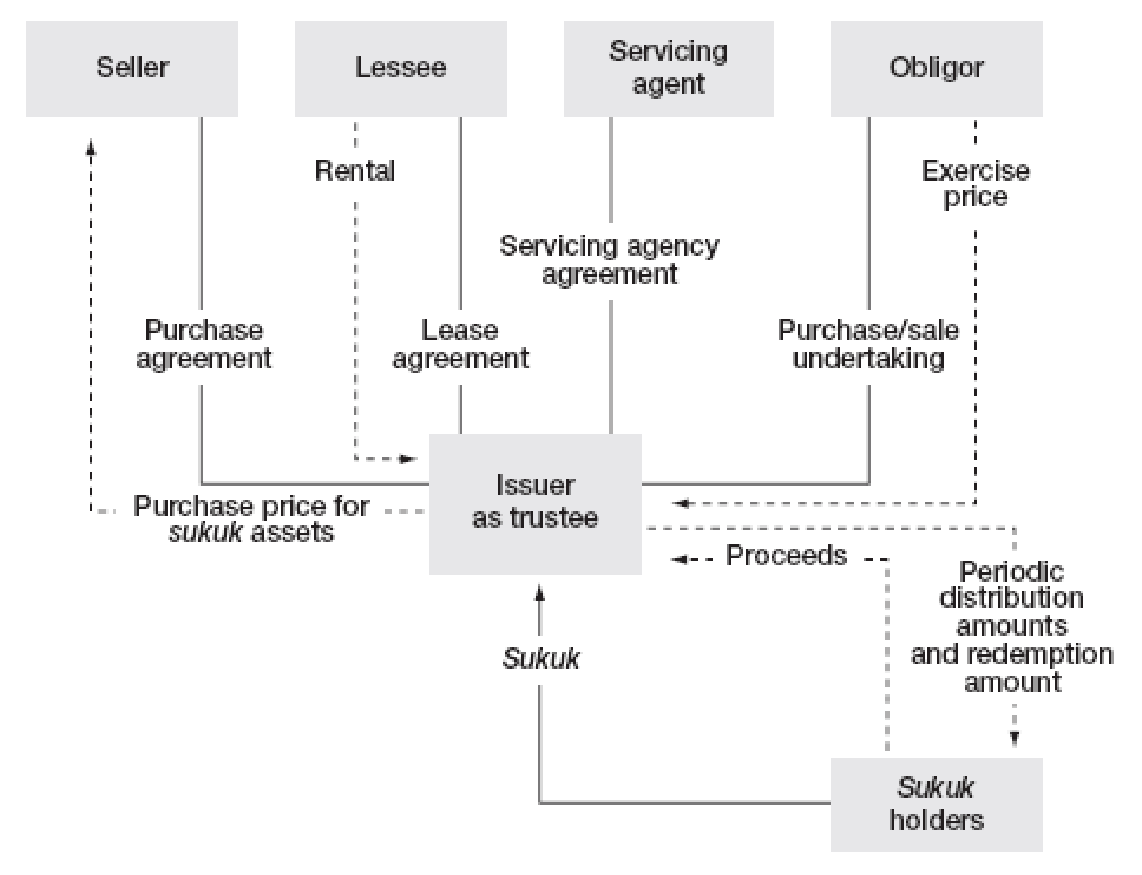

Ali (2010, p.1) and Farah (2008) stated that the main characteristics of this type of products are it is connected to leased properties and assets, ensure equal values; on the other hand, it can be said that sale the leased property (including building) by issuing bond and Sukuk holders are considered as the partners in the ownership of the property. However, Farah (2008) argued that Ijarah Sukuk holders must receive the yearly or monthly earnings from the leased property, investors can sell in the capital market though it involves many issues, for instance, the supply and demand determine the value of the service like if the demand increases than supply will increase as a consequence though other issues remain same. On the other hand, Farah (2008) stated that The facilities and other services determine the value of the property based on the time frame or economic life of the service; in addition, efficient performance of the assets raise value such as value added to the property and properly maintained property can ask higher value; however, the following chart gives more details about Sukuk Ijarah –

Generally, the product structures depend on some specific factors those cannot be avoided by the issuers, for example, the contract agreement and legal framework to ensure Shariah compliance as it is mostly a legal value chain more willingly than a financial value chain (McNamara et al. 2012). At the same time, McNamara et al. (2012) pointed out that the issuers of Sukuk Ijarah focus on some easy, but fundamental principles of Islamic finance, which generates an internal disagreement; in addition, It involves some commercial and tax scenarios (Ali 2010, p.13).

Usufructs of existing assets’

According to the report of Farah (2008), this type of Sukuk carries equal value and the issuers can lease the property in accordance with the consent of the owner of the property; however, such certificates incorporate the rights of the service and the owners have the opportunity to give rent and sub-rent to the third parties and so on.

Table 2: – Shariah rules and requirements. Source: – Global Investment House (2008, p.12)

Usufructs of the future assets’

Farah (2008, p.4) stated that this type of Sukuk certificates issued considering the under constructed projects those need long-time to be completed the projects; however, it is similar with the Salam contract, but an increase of non-leased properties, terms of the contract derived from the religious values of the individuals.

Table 3: – Shariah rules and requirements. Source: – Global Investment House (2008, p.12)

Hybrid Sukuk

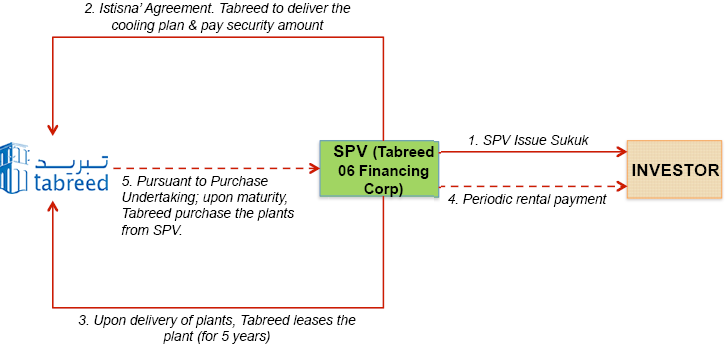

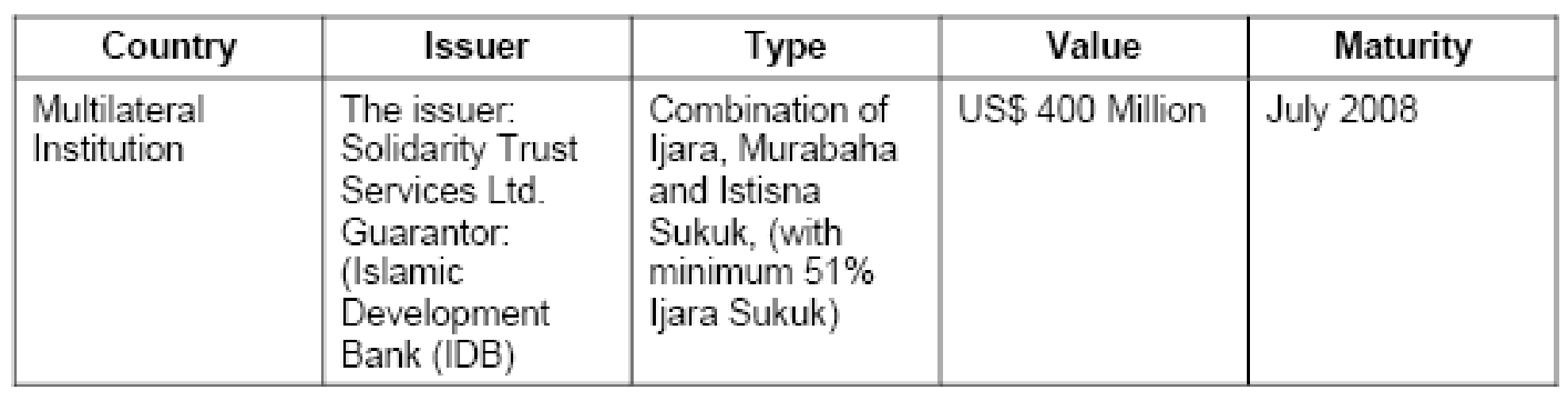

Chik (2009, p.24) stated that this kind of Sukuk introduced in the UAE, which was the combination of Istisna and Ijarah; However, the following figure describe the structure of the Hybrid Sukuk –

In the following diagram Kettell (2008, p.6) pointed out some important features about the hybrid sukuk –

Contractor’s Sukuk

Farah (2008, p.4) stated that when any contractor or suppliers issued sukuk for existing commodities and offered these certificates during a contracted time in the future; however, it carries equal values in accordance with the description of the security and the sukuk holders contribute in the financing, for instance, educational or health programs and they receive one-fourth return.

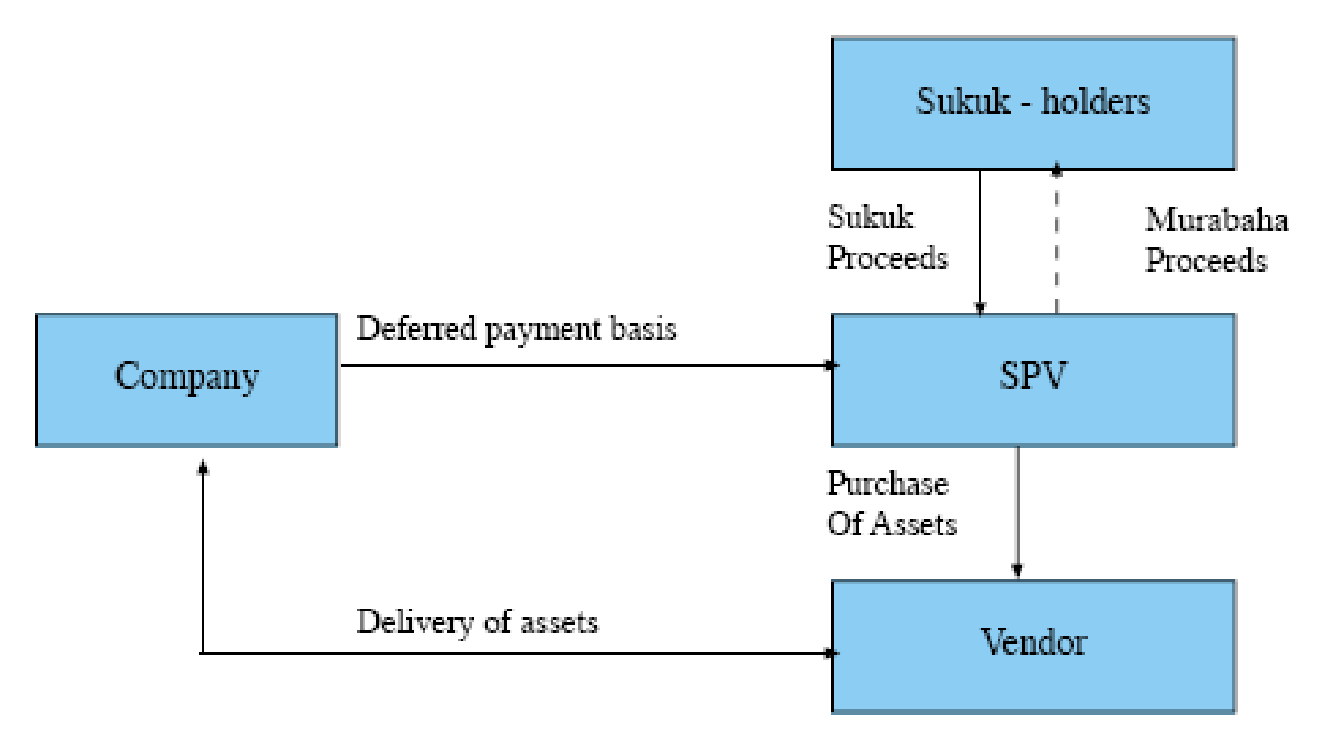

Sukuk al Murabaha Structure

Global Investment House (2008, p.9) stated that Murabaha Sukuk is issued by the merchant or his agent and carries equal values, but it can not be traded in the secondary market at a negotiated price as its sale of debt at a pre-negotiated price or complying the system of Riba; however, the following figure shows the structure of this type of Sukuk –

According to the report of Global Investment House (2008, p.9) and Farah (2008, p.4), the concept of this Sukuk based on Istisna’a contract and it trades only in the primary market and these are not liquid for which the investors’ perspective are different in this segment.

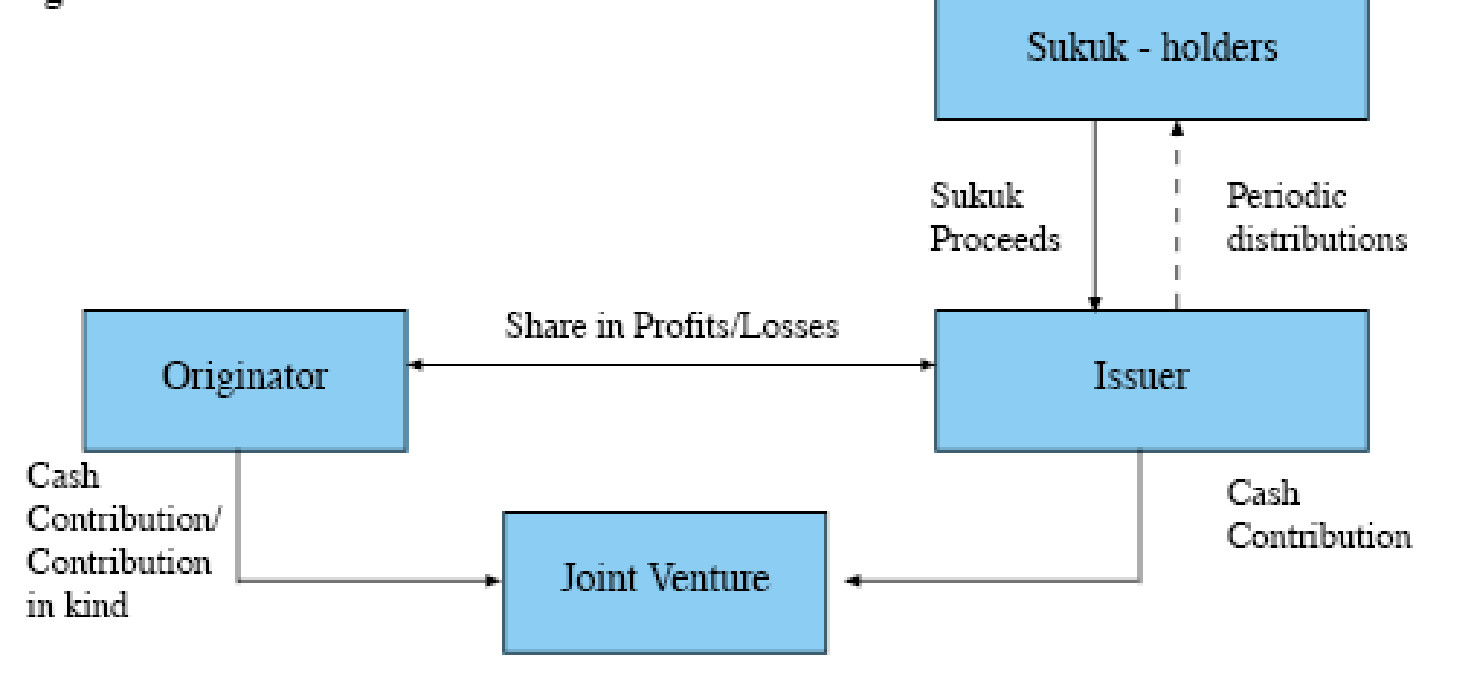

Sukuk al Musharaka

Global Investment House (2008, p.11) stated that Murabaha Sukuk issued by Several corporate entities or the agents to finance a project; organizations considered it an alternative due to their superiority to the issuer’s equity and the investors contribute the capital amount to the issuer, which gives them the opportunity to penetrate the market as joint venture agreement with the financing parties. Nevertheless, the next chart shows the Sukuk al Musharaka structure –

Global Investment House (2008, p.9) reported that this Sukuk carry equal values and losses from the Musharaka business are shared in proportion to the capital investment, but the profits distributed among the parties of the agreement at a predetermined basis; in addition, Farah (2008, p.5) and Ali (2010) stated that structure of Mudarabah and Musharaka is different considering capital investment. At the same time, this type of certificate has issued at the initial stage in order to remove the dilemmas and weaknesses of the Sukuk al ijara structure; however, it was complied with all regulations and become highly popular in the international market (Ali 2010).

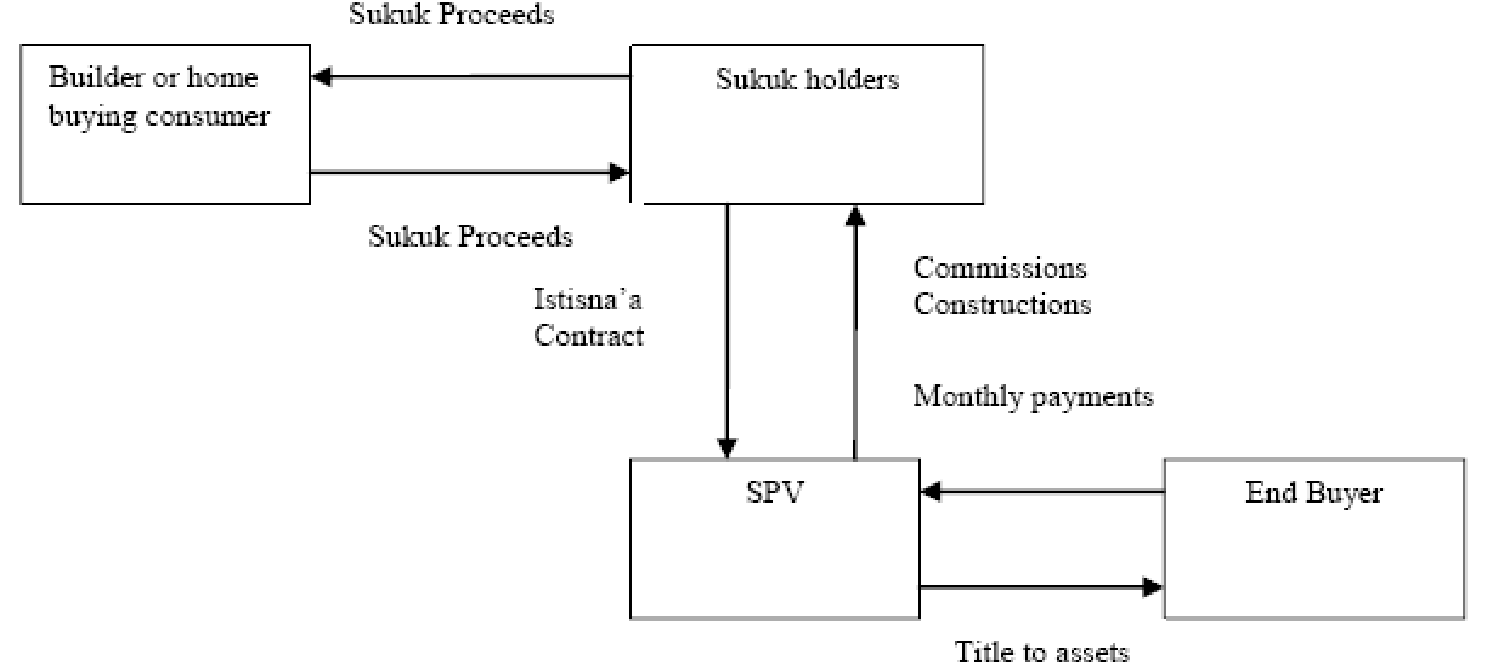

Istisnaa Sukuk

AlSaeed (2012, p.56) stated that SPV issues Istisna certificates to elevate funds for the projects to pay the contractors and title of the properties is transferred to the SPV, which is leased or sold to the end purchaser and the profits distributed among the certificate holders; the next figure shows the structure of Istisnaa certificates –

Table 4: – Shariah rules and requirements. Source: – Global Investment House (2008, p.12)

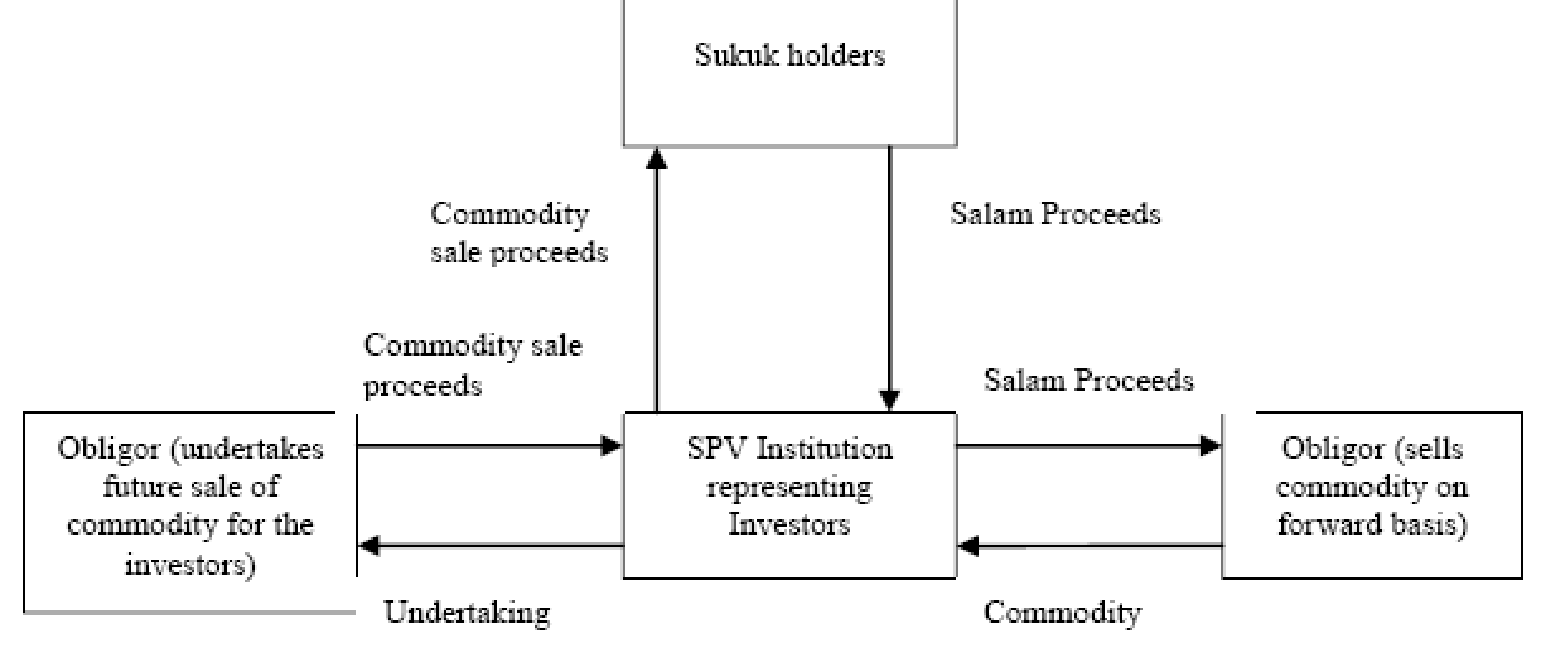

Salam Sukuk

AlSaeed (2012, p.52) stated that the main function of this certificate is to mobilizing Salam capital and this certificate created and sold by an SPV considering all standard Shariah requirements; furthermore, the subsequent diagram shows the structure of the Istisna sukuk –

Table 5: – Shariah rules and requirements. Source: – Global Investment House (2008, p.13)

Sukuk in Saudi Arabia

Rabindranath & Gupta (2009) stated that KSA is observing unparalleled economic growth and engaging in various development projects for which it is essential to have available sources of long-term financing for both the public and private sectors though it has the largest investor bases in the GCC countries. At the same time, Rabindranath & Gupta (2009) argued that the financers have not shown their interest in the long-term projects considering the issues related to financial benefits as well as return on investments, which was one of the most significant causes to leave the large projects at the initial stage of planning. Therefore, it was very essential for the country to introduce such bonds to implement and carry on large projects in the adverse economic condition in the global financial market though it faced severe problems at the very beginning of its operation to comply with all the provisions of Shariah law and other financial barriers. Rabindranath & Gupta (2009, p.4) expressed that it was too hard for issuers and the customers to follow strict rules of Islamic law, but the establishment of a new stock exchange removed these problems though the entire process had taken a long time to cover all issues in this regard. As a result, the size of Sukuk market of KSA is relatively small considering the size of the bond market of Malaysia and other GCC member states; for instance, there are only two large issuers according to the report of Tadawul and these are SABIC and SEC (SAMA 2011 and Rabindranath & Gupta 2009, p.1).

According to the annual report of SAMA (2011, p.82), the stock exchange introduced the latest electronic market to trade Sukuk along with bonds in the middle of 2009 and issued Rls 28.0 billion Sukuk as well; in addition, the Capital Market Authority had passed new regulation and implemented the regulatory framework in order to increase the number of customers. As a result, it became easier for the four-brokerage companies to join Tadawul to offer financial intermediary services; SAMA (2011) reported that KSA share price increased by 8.2% in 2010 and total investment funds went up by 5.2bn and became 95bn within a year. However, CMA is responsible to adopt a legal framework to control the domestic capital market under the provisions of the Corporate Governance Regulations though it does not give any specific framework for this bond market since the characteristics of different types of Sukuk are different, for instance, some bond structures would not make any debt obligation (Rabindranath & Gupta 2009, p.4).

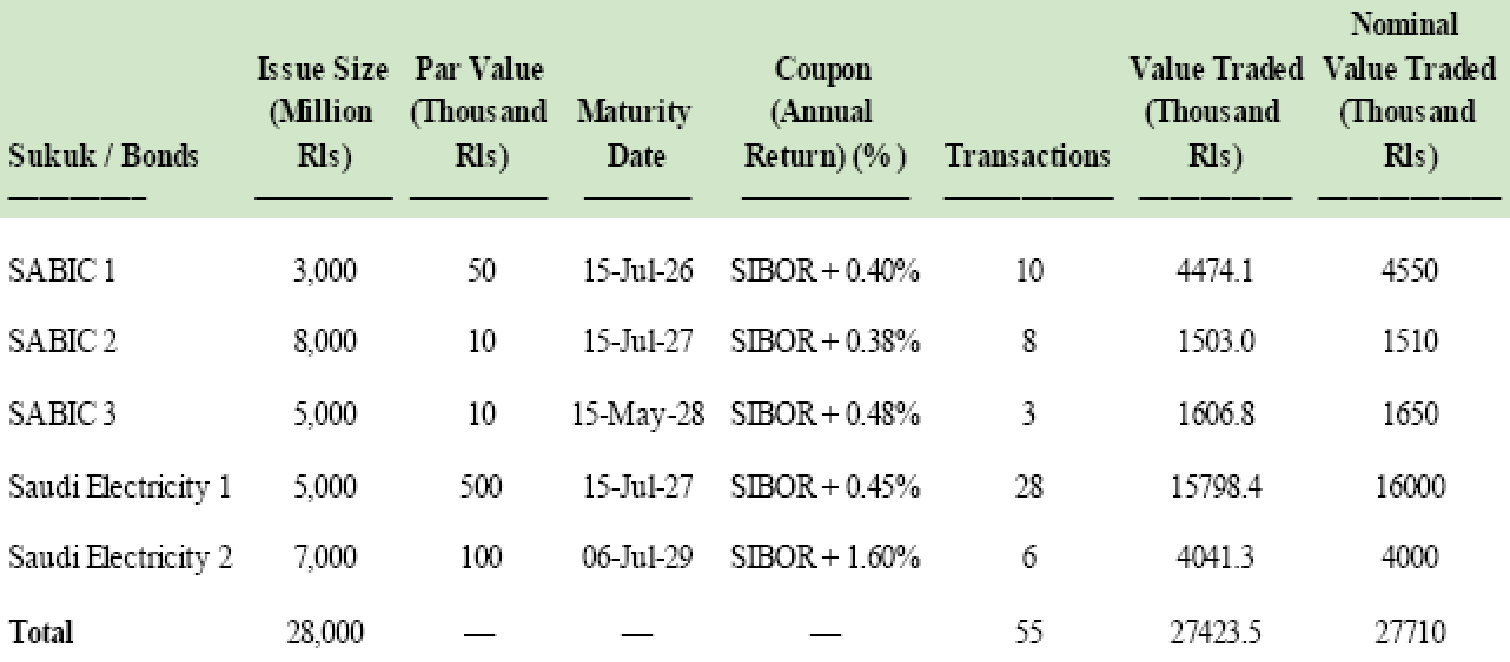

According to the annual report of SAMA (2010, p.82), the total amount of issued Sukuk was Rls 28 bn at the end of 2009 and there were only five issuers among them SABIC issued three items and SEC issued two items; however, SAMA (2011) reported that total amount of issued bonds increased by more than Rls 7 bn. In addition, the total issued Sukuk in 2010 was more than Rls 35 bn (SAMA 2011, p.82) and three new issuers joined this industry; however, the following gives more details to show the differences between the position Sukuk in the end of 2009 and 2011 in the stock exchange of KSA –

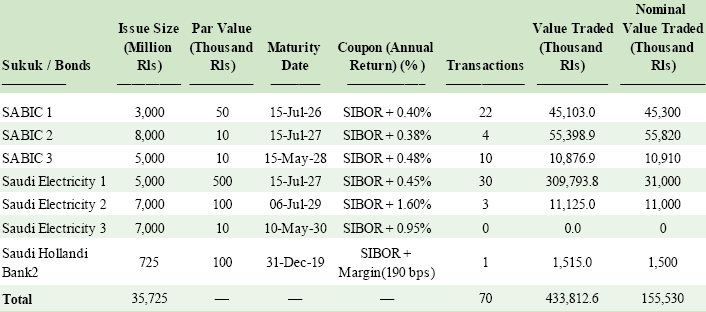

At the same time, Al-Ghorairi (2011, p.104) argued that sukuk played vital role for the growth of the insurance sectors of the KSA since growth rates were amazing; moreover, Sukuk evidenced popularity in the Saudi Islamic capital market; so, Al-Ghorairi provided the following chart in order to show market share of Sukuk in the GCC market –

Table 6: – Breakdown by country. Source: – Rabindranath & Gupta (2009, p.14)

The above-mentioned figure demonstrates that Saudi Arabia holds 30% share of the GCC Sukuk markets, which was the second-largest market in this zone; in addition, the above table demonstrates that KSA holds the third position in the global Sukuk market by capturing more than 12.7% total share. However, Rabindranath & Gupta (2009, p.14) stated there are three types of Sukuk issuers in this country, such as, 47% of issuers were sovereign, 33% issuers were quasi-sovereign and only 20% were corporate issuers; in addition, there many sectors, which presents in the next figure –

Table 7: – Breakdown by sectors and currency. Source: – Rabindranath & Gupta (2009, p.14)

Economic and financial challenges

Jobst et al. (2008, p.12) stated that the recognition of fundamental reference assets as well as security designs, return of capital, the absence of structural features that are not permissible in the Islamic context (such as, repayment assurance and credit augmentation), frequently-used risk management instruments are not acceptable to most shariah scholars and so on. However, Jobst et al. (2008, p.12) further addressed that asset management mechanism particularly the trading of a debt security is one of the greatest economic challenges of the issuers and regulators; in addition, interest rate or credit risk management system, loss of issuers’ confidence because of limited historical performance in some places, and lack of product development in the industry. At the same time, Jobst et al. (2008, p.12) raised some other financial challenging issues, such as the characteristic “buy & hold” investment strategy, tax disincentives to issue Sukuk, and the case with conventional debt funding and so on.

Legal and regulatory challenges

According to the report of Jobst et al. (2008, p.13), it is essential to comply with the provisions of both commercial and shariah law and Islamic jurisprudence is neither specific nor bound by the doctrine of binding precedent and maintenance of the regulatory standards in the aspect of shariah compliance and the absence of broadly familiar legal principles. At the same time, other key legal challenges are the contradictory legal framework for asset control along with bankruptcy rules for the investors in non-Islamic nations, vague creditor rights and enforcement of asset claims; furthermore, there are different Islamic organizations like Islamic Financial Services Board, IIFM, and so on, those provide several recommendations for the development of Sukuk structures.

Bonds and Sukuk market in the GCC market

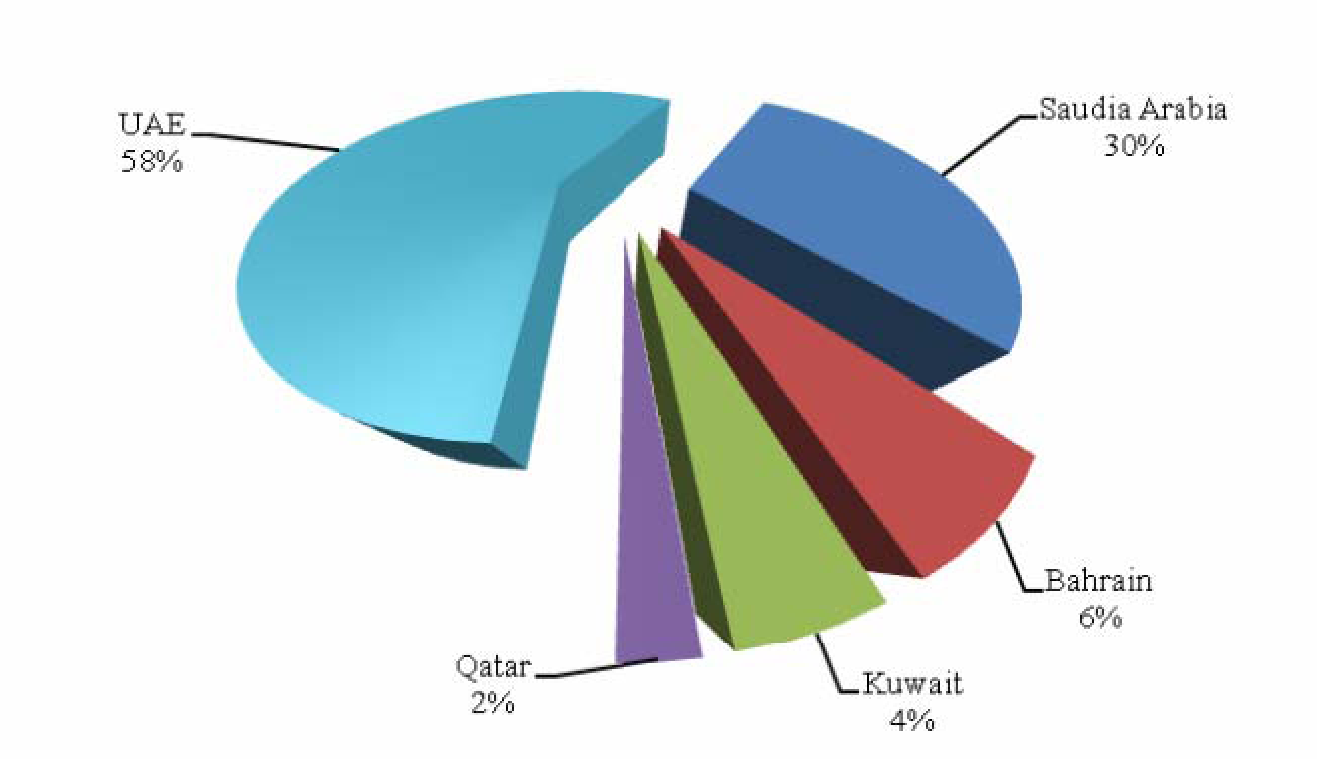

According to the report of Kuwait Financial Centre (2012, p.1), the issued Sukuk market experienced gradual improvement year by year from 2003 though it was decreased in 2010 slightly due to the adverse impact of global economic downturn, for example, from 2004 to 2011, the total amount increased by $63290 million. On the other hand, Markaz Research (2012, p.4) stated that the amount of total conventional bonds market had increased significantly in 2009, but it was decreased within two years; however, the following figure and table gives the information about the collective Bonds Market of GCC –

Figure 8: – GCC Conventional Bonds Market from 2003 to 2012. Source: – Kuwait Financial Centre (2012, p.1)

Sukuk Issued in the GCC countries

The above mentioned table and figure demonstrate that aggregate bond market experienced success, which influenced the new issuers to incorporate and contribute in the market, but following data of Kuwait Financial Centre (2012, p.1) represented that the total amount of issued Sukuk decreased by US$ 8869 million within four years; following table gives more data about Corporate and Sovereign Sukuk –

Table 9: – Sukuk Issued in the GCC countries from 2007 to 2011. Source: – Self generated from Kuwait Financial Centre (2012, p.5)

From this table, it also can assume that corporate issuers have showed less interest in the fiscal year 2008 and 2010 due to severe external barriers and adverse economic condition in the GCC countries; at the same time, the amount of sovereign issued Sukuk had also decreased from 2009 and the amount was same in 2011 (Kuwait Financial Centre 2012, p.5).

Table 10: Sukuk issues in GCC member states from 2006 to 2010. Source: Self-generated from Farah (2008) and

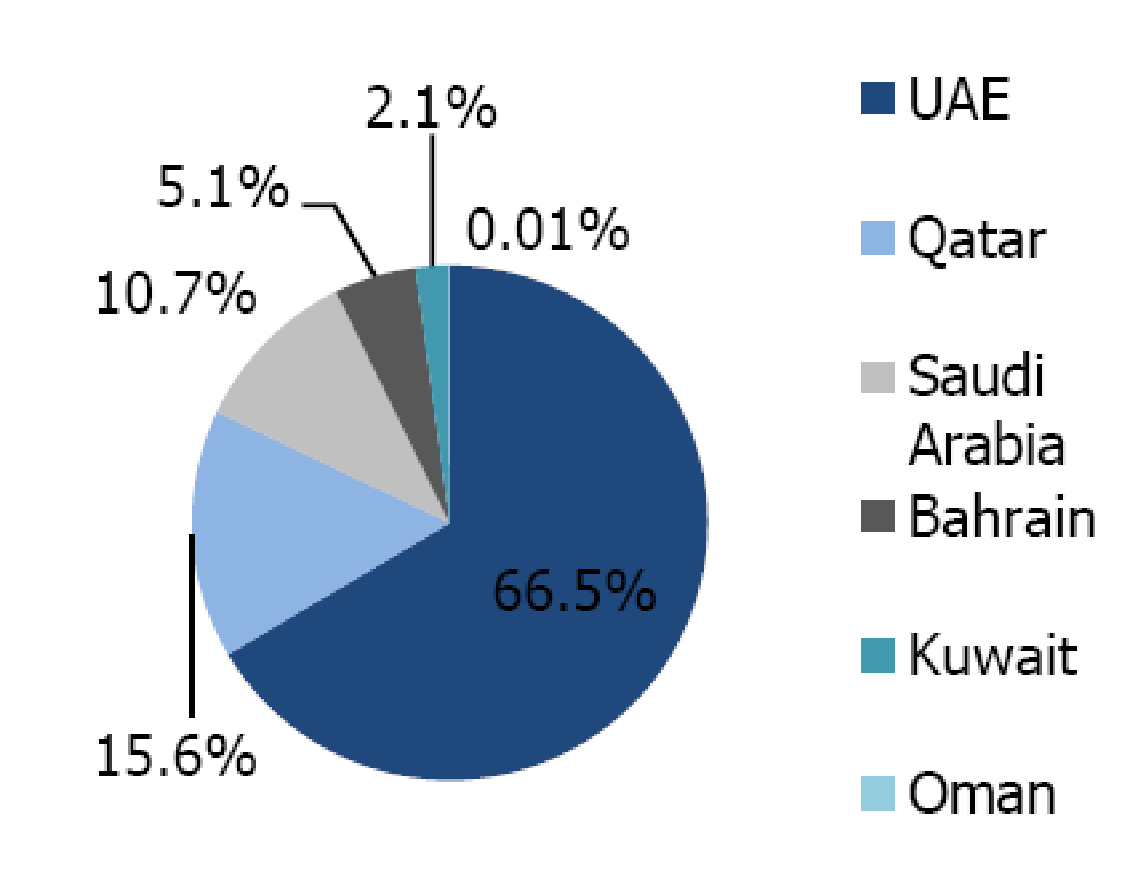

In the GCC bond market the UAE hold the strongest position by issuing 66.49% of total Sukuk and Qatar was the second largest situation by issuing 15.60% of total Sukuk in the GCC market; however, the following figure demonstrates about other GCC countries –

Among the GCC members, Oman has not concentrated in this sector while the central bank issued only US $2.8 million; the market of Saudi Arabia decreased gradually from the fiscal year from 2006, for instance, total amount of issued sukuk was more than 37% in 2007, but it decreased by 21.4% within four years –

From the trend of the Sukuk issuers in this zone, it can be argued that the policy maker of the UAE have concentrated on the diversification economy and issued more sukuk to hold largest share of the capital market, for example, total amount of issued sukuk the UAE was approximately 58% in 2006 and it decreased by 7% in 2007. However, this situation of the UAE Sukuk market had changed by the next four years and increased by 15.5%.

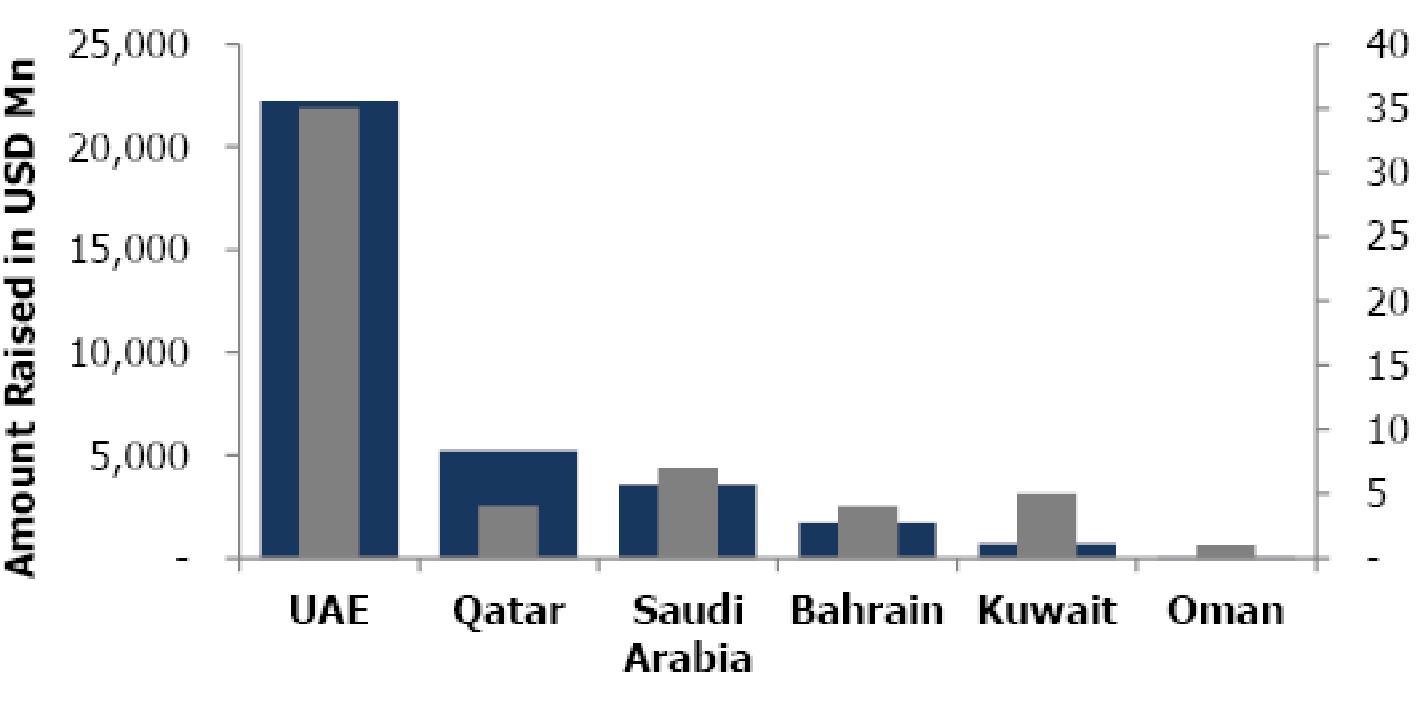

On the other hand, Markaz Research (2012, p.2) stated that GCC central banks are responsible to control the levels of domestic liquidity while more than 20% of total bonds considered sukuk; however, the next figure shows the amount of issues and number of issuers –

Breakdown by Sector

Table 11: – GCC Bonds Market Sector Breakdown H1 2012. Source: – Self-generated from Kuwait Financial Centre (2012, p.3)

Growth of Sukuk in 2012 in Stock Market

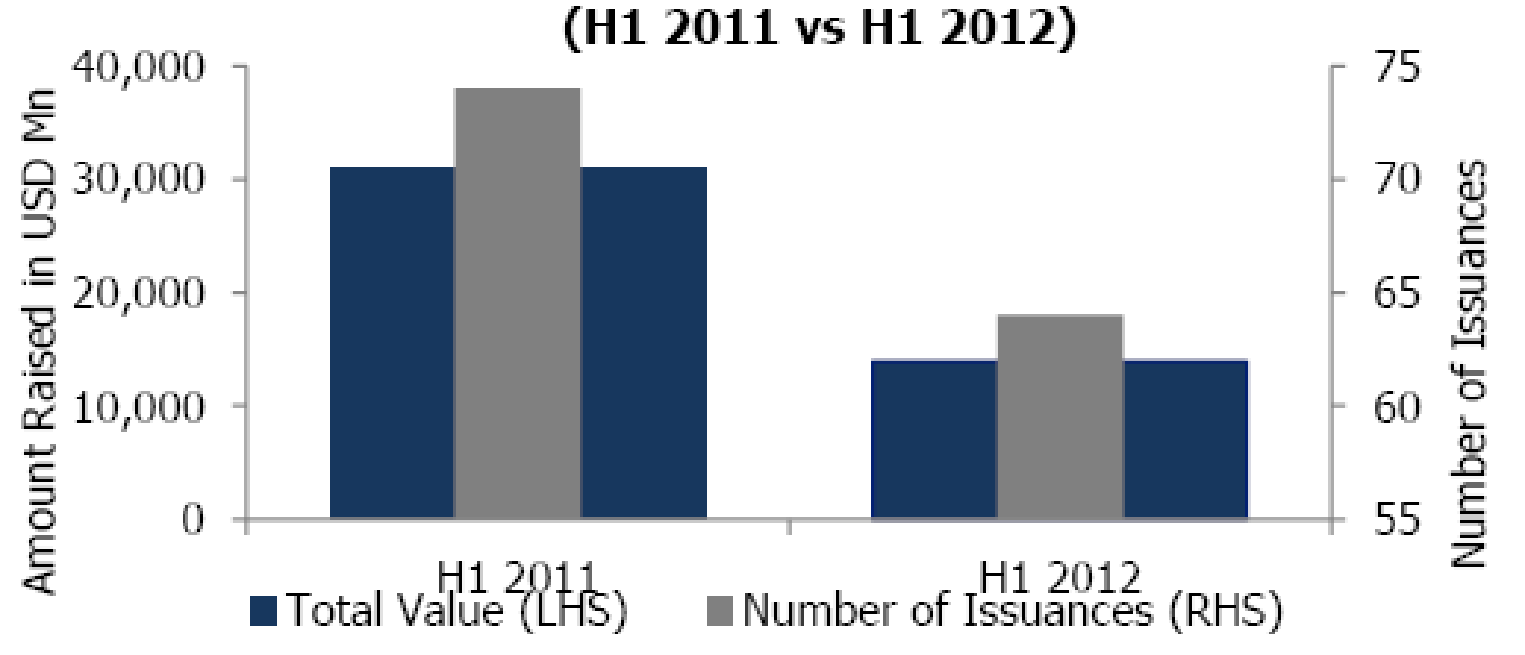

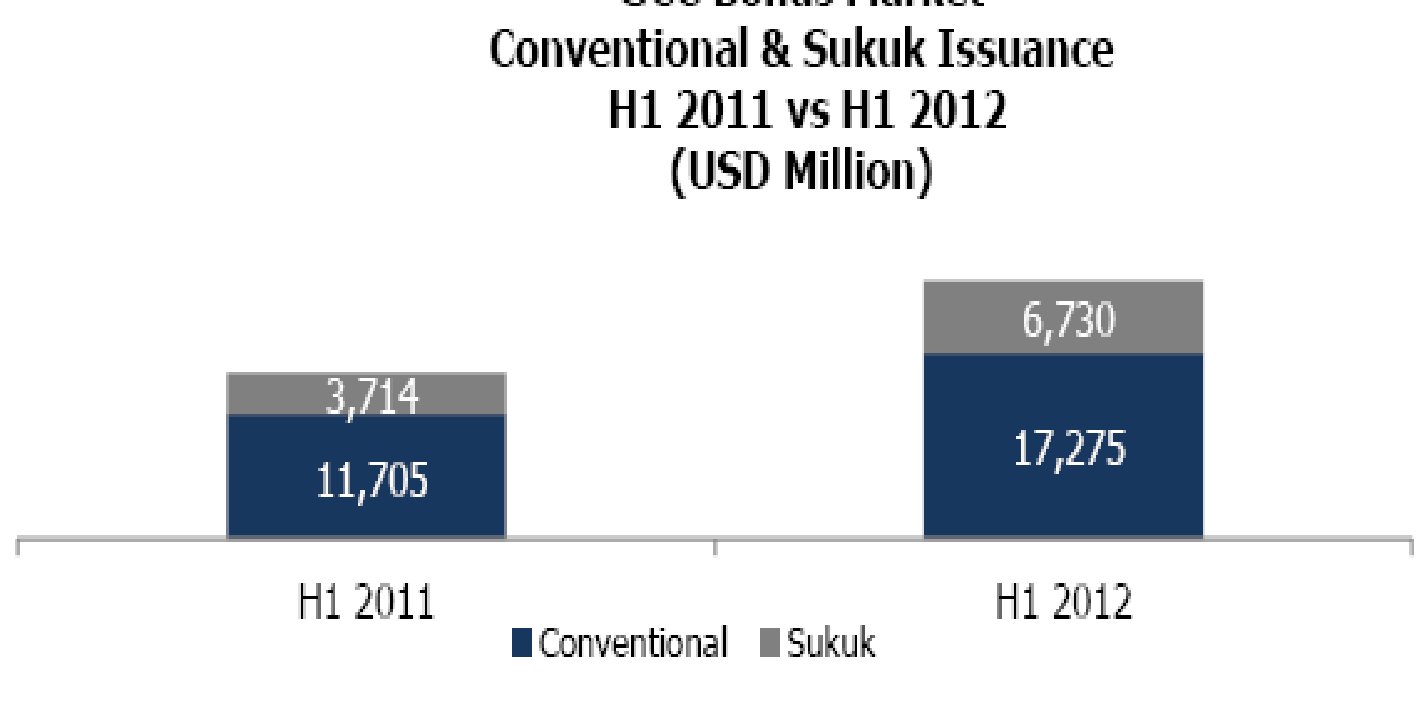

Rahman (2012) reported in the Gulf News that the global Sukuk market grew by $141.5 bn, and reached more than US$ 292 bn; at the same time, Reuters (2012) represented that GCC Sukuk market particularly corporate and infrastructure segment would experience excellent growth due to several reasons, such as, increasing oil prices help to lift GDP growth in this zone. However, Reuters (2012) pointed out some other potential factors those influence the Sukuk market in the MENA region, for instance, positive rating actions across GCC Sukuk portfolio over 6 months, rise reliance rate on the Islamic equivalent of bonds, stable regional economy and capital market, financial system’s sound liquidity, accommodative monetary policies and so on. Moreover, Reuters (2012) reported that unpredicted global economy, diverse property markets in this region, and continuous political crisis remain the main challenges available alternative conventional bonds, a niche market instrument, clog growth channels, Sukuk structures involve Deficiencies and problems in the secondary market related with investor rights, transparency, and illiquidity. In addition, Rahman (2012) further reported that there are some negative factors that can create hindrance for the development of the Sukuk market, for example, documentation problems, criticisms of the learners and researchers, market of Oman shows little growth, lack of issuers in some countries, lack of an Islamic megabank, and the dilemmas due to the Arab Spring. At the same time, Reuters (2012) and Rahman (2012) further reported that Sukuk issuance beaten conventional bonds in the GCC zone; however, the next figure gives the information about comparison of conventional and Sukuk –

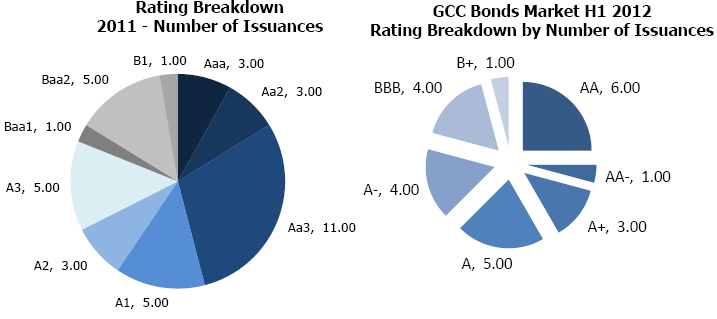

Rating Breakdown by Number of Issuances

AlSaeed (2012, p.63) stated that IIRA Bahrain Monetary Agency –

Secondary Market of Sukuk

Harvey and Cosgrave (2012, p.1) pointed out that the Islamic asset managers have engaged to arrange capital from the Sukuk with a tradition that the primary buyer would preserve their Sukuk certificate until the maturity, such theoretical alignment of the introducers have generated enough obstacles to establishing the secondary market of the Sukuk. Another theoretical dilemma of the ancestors of Sukuk is that they have in mind that they would only sell this financial product to the religious-minded Muslims not to the other religious followers. Due to the fractional outlook, they could not take into account the global market and failed to design the product features in accordance with the other international bonds that prevailed in the market. During the introduction of Sukuk, the initiators thought that they would keep the product purely with Islamic attributes, while trading of debts certificates with fixed rates would particularly align with some uncertainty of success or failure which Islam has identified as ‘Gharar’ and made it strictly restricted, so Sukuk need not have a secondary market. The trading that conducted in the secondary market would be based on the fixed rate of return that any rational person would explain it as an interest and the Islam identified it as Riba and without any hesitation made it strictly prohibited by the law of Al-Quran, no Fiqah would be adopted in this regards. On the other hand, the price of any financial commodity in the financial market goes up depending on the rumors and greediness or hunger for a quick profit that the civilized society identifies as a trend of Gambling and Islam has pointed it as the ‘Maisir’ which is severely restricted in the lifestyle of the Muslims. Thus, the ancestors Sukuk has failed to realize that it may have emergence for the secondary market to a competitor in the global market with its success and uniqueness by crossing the border barrier of the religious outlook.

Rauf (2012, p.4) explored that there are twenty-two banks enlisted in the London Stock Exchange (LSE) are offering Islamic financial products and services where at least eighteen banks are the issuer of Sukuk with a capital accumulation of US$ 10 billion while 60% of the global Sukuk issuers are from Middle East countries, 30% from Asian and rest 10% from Western countries. In Luxembourg Stock Exchange, there are fifteen Islamic Financial Institutes who are the issuers of Sukuk with a capital accumulation of Euro 5 billion, which is a remarkable indication of Sukuk in the western financial arena. In the Stock Exchange of Dubai, there is second-highest number of Sukuk issuers enlisted with remarkable capital accumulation while the western financial institutes in France, the Irish Republic, and the USA have started to introduce Sukuk in their market and there are almost 40 funds promoted by the different investment companies.

Considering the tremendous success of Sukuk in the global financial market, the issuers of the Sukuk have drawn their attention to the secondary market and looked for the theoretical explanation regarding the incorporation of the secondary market; they have already hired some Fiqah practitioners to find the way out to legalize secondary market from the Islamic viewpoints. Although by the contribution of Quran and Sunnah, there is no chance to legalize the Riba, Maisir, and Gharar, the trading of Sukuk in the secondary market has aligned with the same attributes it is the discretion of the Fiqah practitioners, how they provide a prescription to introduce or incorporate secondary market with the aim to gaining further growth in the Sukuk market. The Fiqah practitioners may suggest not to use religion integration in the secondary market, on they can provide new theories with the debt trading in the secondary market, which may generate new debate in the religion as well as Islamic financing institutes globally.

Al-Saeed (2012, p13) argued that the Saudi Stock Exchange has started its journey in 2007, but still, now there is no formal secondary market for Sukuk trading in KSA, the Tadawul has engaged function of regulating the market trading for tradable shares and stocks, the emergence of trading Sukuk has been gaining more importance with rising demand for long-term financing. It is notable that due to ethical dilemma, religious radicalism, the backwardness of the product feature and regulatory framework the growth of Sukuk and its secondary market has been seriously hampered although there is rising demand for long-term financing while equity or governmental financing is not sufficient to meet the rising market demand for capital needs in the private and public sector. In the KSA market, due to lack of secondary market the investors are less interested to involve their money for Sukuk thinking that while they face any emergency to liquidate the Sukuk certificate they cannot bring back cash by trading that, only the idle domestic money goes to involve at Sukuk and there is no attraction to attract further investors.

Tariq (2004, p.60) explained that the demand for any product of the primary market is deeply interlinked with the expansion and growth of the sustainable secondary market for that financial instrument, different researches demonstrated that the Muslim savers and investors have no major reluctance to the conventional financial products. The investors of most Islamic countries have no strong reservation to invest in conventional bonds or western banking, thus, if local law does not impose any embargo most investment would go to the conventional bonds due to the absence of secondary market and the Sukuk certificate holders may not align with any burden of risks for not timely liquidation. There are some countries where Islamic financial products like Sukuk has amalgamated the traditional secondary market granting them tradable attributes, in other Islamic countries they are trying to introduce further Islamic secondary market while the primary objectives of the Islamic secondary market Islamic color to attract the investors suffers from religion emotion including the marketability of Sukuk. On the other hand, the Islamic secondary market establishment is deeply concerned with the superior informational flow, easy access to the market and hindrance free movement of the investors without any pressure investor would allow to trading his Sukuk certificate at any moment that he feels appropriate and it would be individual’s choice when he decides for liquidation.

Sukuk in the Global market

Y-Sing (2012) reported that 2012 was a challenging year for the new entrants of Sukuk market, such as Oman and Egypt; however, the Sukuk market experienced huge success in 2012 because the market leaders have recovered from the financial crisis, and transform agendas and change some policies to give facilities in accordance with the Islamic law and so on. Y-Sing (2012) and Reuters (2012) presented the report of Ernst & Young, which included that Egypt and Iraq had scrutinized the Sukuk market in order to develop a legal framework to introduce Shariah-compliant products, and Libya had already implemented Islamic banking regulation; however, established and new banks have focused on the Islamic Sukuk products throughout the MENA region. On the other hand, Ernst & Young (2012) and Y-Sing (2012) reported that the entire industry expected to reach more than $1.80 trillion by 2013; however, the traders of this industry are under continuous pressure to increase profit margin from Islamic banking because the characteristics of such banking system still behind from conventional banking. From 2008 to 2011, aggregate return on equity for Islamic banking was merely 11.60%, which was more than 3.70% less than from other banking sectors; however, this sector faces many problems. such as sub-scale procedures, inadequate engagement with customers, fundamental jeopardy culture, imperfect market segmentation, and lack of scientifically oriented value proposition (Ernst & Young 2012).

Y-Sing (2012) reported that provided following data to describe sales growth –

Table 12: – largest sales in 2012. Source: – Self generated from Ernst & Young (2012)

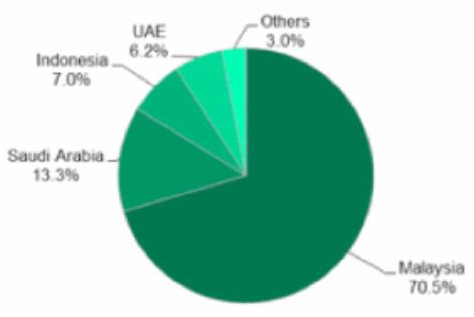

Saudi Gazette (2013) reported that the volume of sukuk issuance in the first quarter of 2012 was more than $66, GCC issuances amplified near 112% (excluding Kuwait and Qatar) and the secondary market grew to $211 bn; Malaysia dominated the market by holding more than 70% and issuing $46.8 bn sukuk in first quarter and $18 billion in the second quarter; however, the next figure shows –

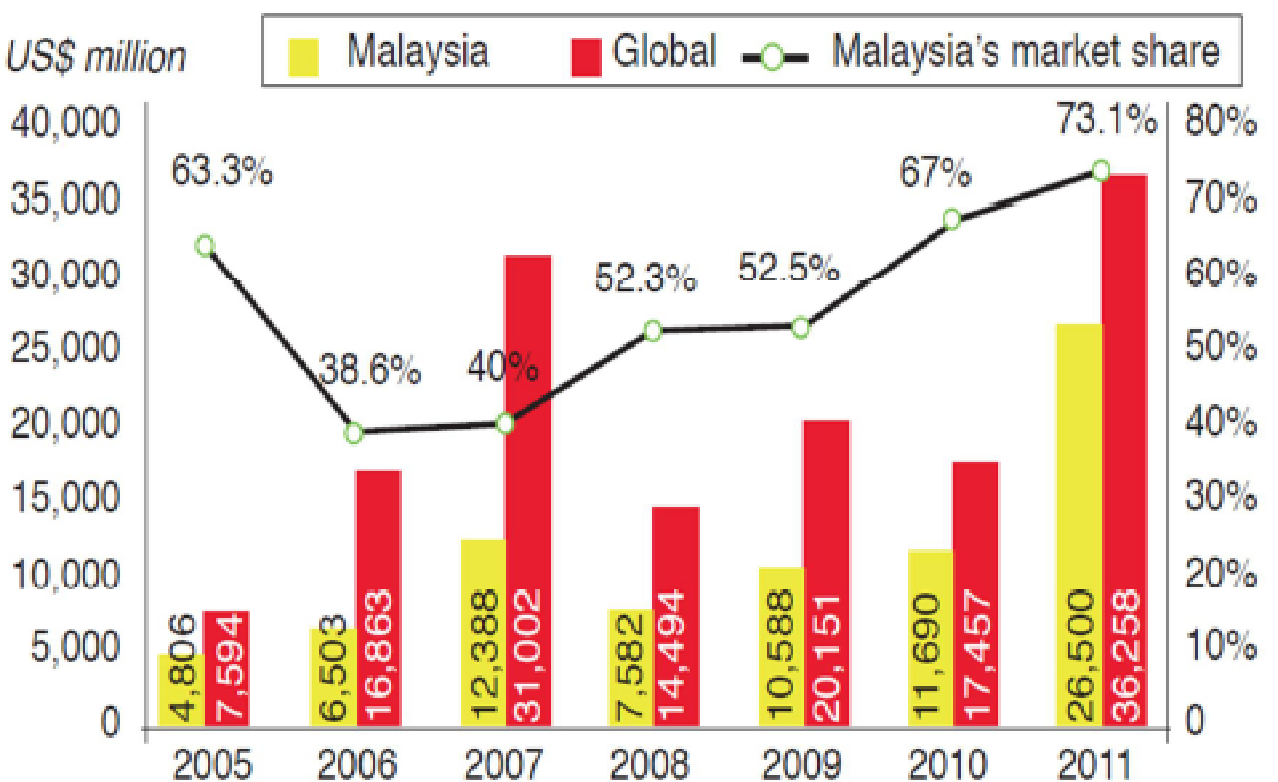

From the last five years tread of the sukuk market, it can be said that Malaysia has always hold the top position in the global market and the following figure related with in the comparison between Malaysian and global Issuance, for instance, this country has captured more than 73% share in 2011 –

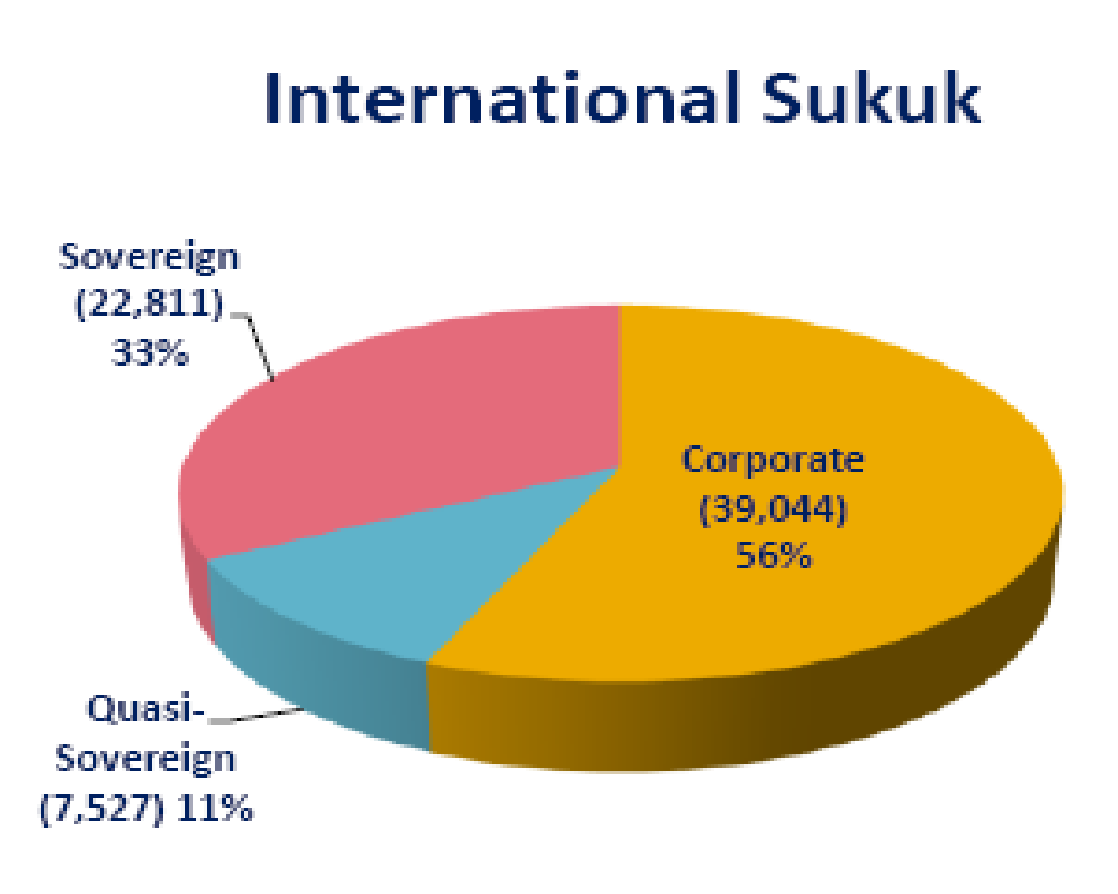

IIFM (2012, p.6) stated that corporate issuers are more interested about this segment in order to raise fund for the different purpose complying laws –

According to the report of Ernst & Young, top twenty Islamic banks captured more than fifty percent of global Islamic banking assets and focused on the seven new emerging markets to implement expansion plan; in addition, industry continues to record robust growth with 16% enhancement in the last 3 fiscal years. However, Global Investment House (2008, p.17) stated that the UAE is in the largest position in terms of number of issuers, for instance, among 137 issued about 58 issues were from the UAE; however, the subsequent chart demonstrates about Sukuk Issuance in terms of number of issues –

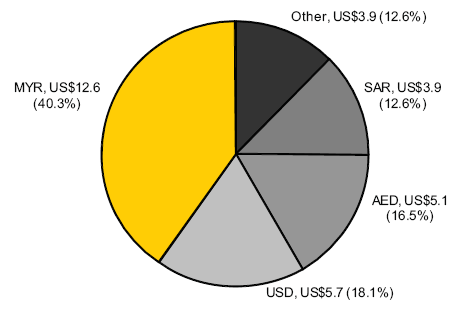

On the other hand, the total number of issues in the global market was only 295 and the share of US$ issuance in the sukuk market declined (only 10 sukuk issues were denominated) from the fiscal year 2007; however, the next charts show that Malaysian Ringgit was in the highest position in terms of number of issues –

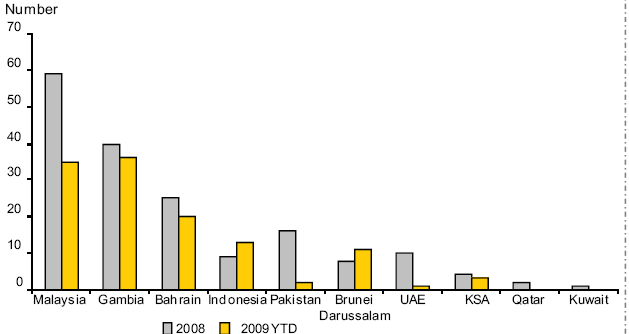

McNamara et al. (2012, p.111) stated that Malaysia issued the greatest value of sukuk in the fiscal year 2008/09; on the other hand, the central bank of Gambia and Bahrain had played vital role to issue more sukuk at that time frame, but the aggregate value of issuance from the African country was undersized than vale of other countries –

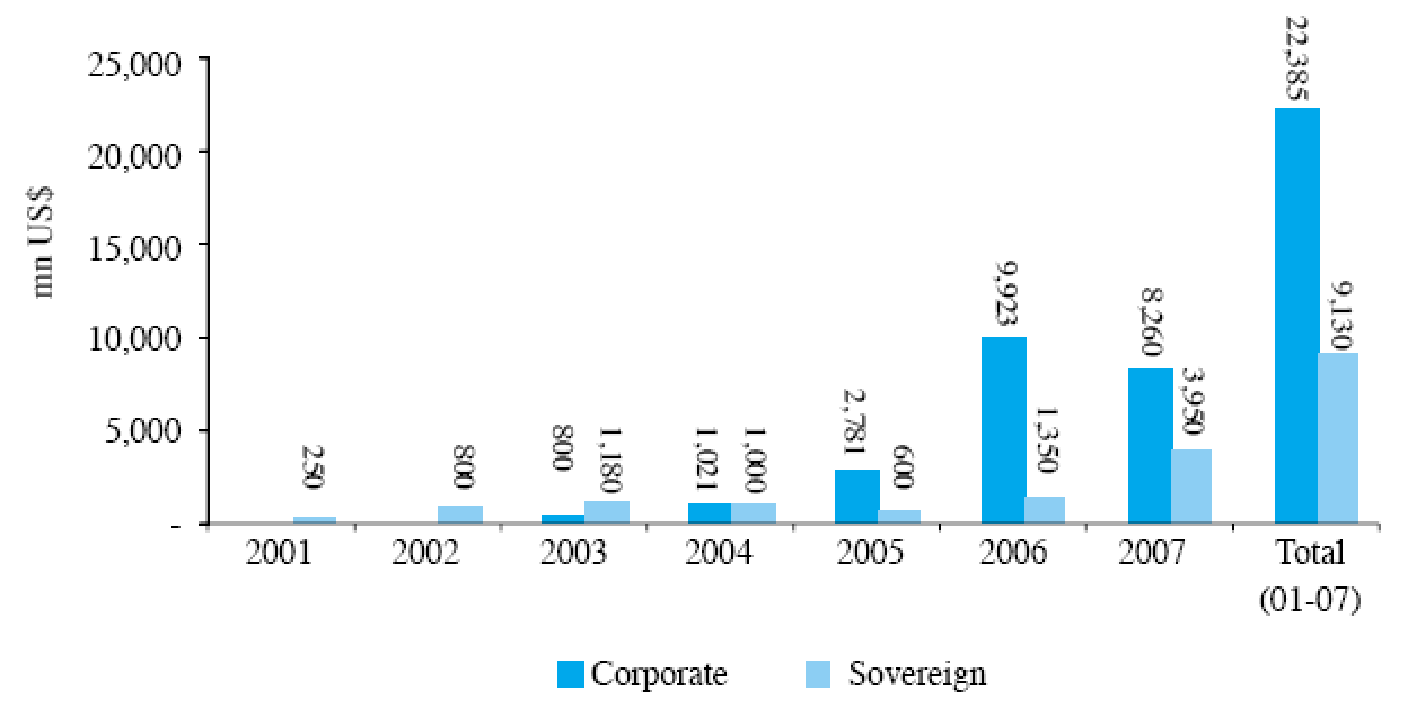

Here, it is significant to note that the amount of issued corporate sukuk had increased dramatically from the fiscal year 2006 and Global Investment House (2008) demonstrated that corporate issued sukuk reached by $22385 million from within five years, but sovereign issued sukuk experienced comparatively lower growth due to several factors –

Impact of the global financial crisis on Islamic Bond Market

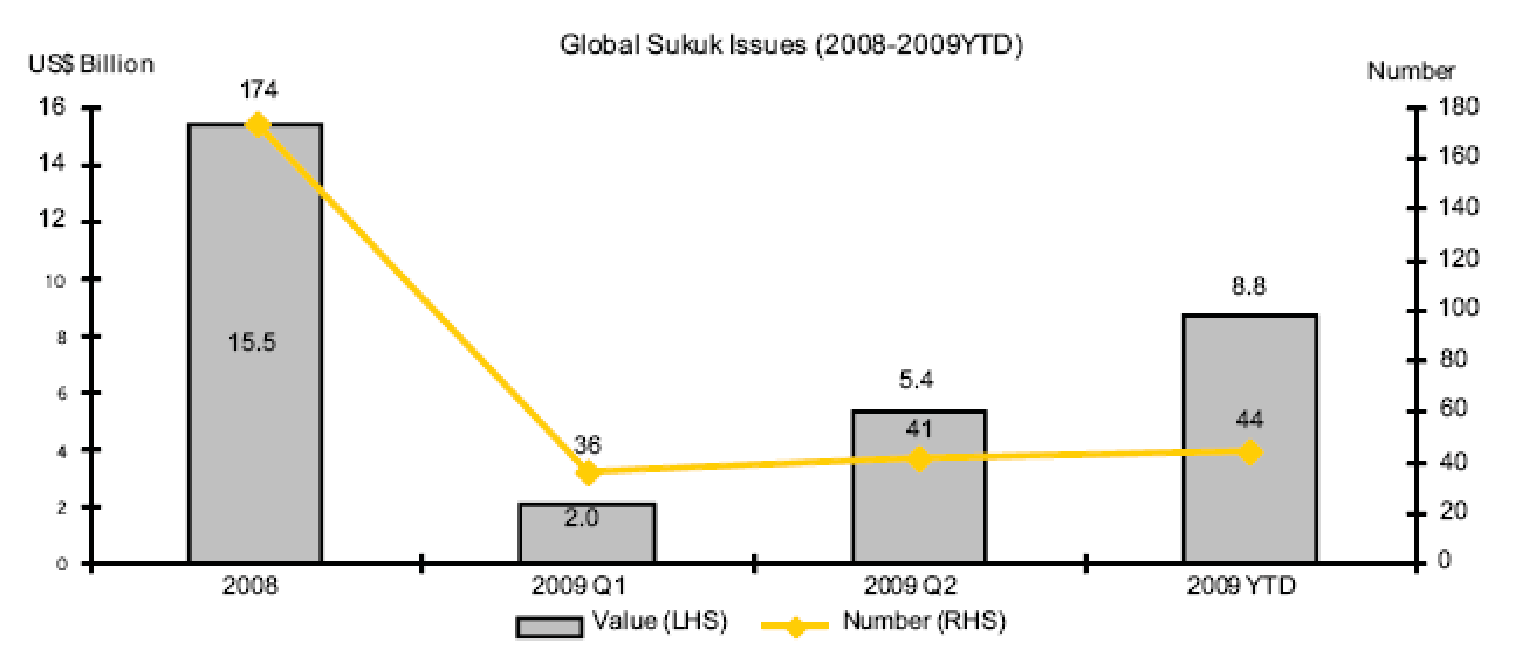

McNamara et al. (2012, p.109) stated that Sukuk issuance dropped from $34 billion to more than %15 billion from 2007 to 2008; however, this fall was continued and reached only $2 billion in the global market; at the same time, number of total issuers were 174 in 2008, which decreased dramatically since their was only 36 issuers in the first quarter of 2009 –

Conclusion

From the above discussion, it can be said that Sukuk is one of the most significant pillars of the capital market to raise funds, but this product faced several problems in order to comply regulation. On the other hand, the position of these products dropped dramatically during the recessionary period, but it experienced outstanding success in 2012; therefore, the issuers and investors are willing to expand the market particularly in the MENA and GCC region in the future.

References

Ali, R. (2010). An overview of the Sukuk market. Web.

AlSaeed, K. S. (2012). Sukuk Issuance in Saudi Arabia: Recent Trends and Positive Expectations. Web.

Bothra, N. (2011). The Understanding of Sukuk. Web.

Chik, M. N. B. (2009). Sukuk: Shariah Guidelines for Islamic Bonds. Web.

Ernst & Young. (2012). Global Islamic assets are expected to reach $ 1.8 trillion by 2013. Web.

Farah, A. F. (2008). Sukuk (Islamic Bonds) and Development Financing. Web.

Global Investment House. (2008). Sukuks – A new dawn of the Islamic finance era. Web.

Harvey, D. & Cosgrave, B. (2012). Liquidity and secondary markets in Islamic finance. Web.

IIFM. (2012). Sukuk Market Overview & Structural Trends. Web.

Jobst, A. Kunzel, P. Mills, P. and Sy, A. (2008). Islamic Bond Issuance— What Sovereign Debt Managers Need to Know. Web.

Kamali, M. H. (2007). A Shari‘ah Analysis of Issues in Islamic Leasing. Web.

Kettell, B. (2008) Islamic Bonds (Sukuk) Case Study (7). Web.

Kuwait Financial Centre. (2012). GCC Bonds & Sukuk Market Survey. Web.

Markaz Research. (2012). GCC Bonds & Sukuk Market Survey. Web.

McNamara, P. Ijtehadi, Y. & Yasaar, M. (2012). Collaborative Sukuk Report. Web.

Rabindranath, V. & Gupta, P. (2009). An Overview – Sukuk Market in Saudi Arabia. Web.

Rahman, S. (2012). Global Sukuk issuances hit $121b in 2012.Web.

Rauf, A.L. (2012). Emerging Role for Sukuk in the Capital Market. Web.

Reuters. (2012). TEXT-S&P report says GCC Sukuk issuance beating conventional bonds. Web.

SAMA. (2010). Annual Report of Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency. Web.

SAMA. (2011). Forty-Seventh Annual Report of Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency. Web.

Saudi Gazette. (2013). Global Sukuk market to sustain growth in H2. Web.

Tariq, A. A. (2004). Managing Financial Risks Of Sukuk Structures. Web.

Wan, T. Y. (2007). Sukuk: Issues and the Way Forward. Web.

Y-Sing, L. (2012). Sukuk Seen Topping $46 Billion Record on Debuts: Islamic Finance. Web.