It is a kingdom of living organisms that contains eukaryotic, heterotrophic organisms whose cells are enclosed by cell walls. Initially, they were considered part of kingdom Plantae due to their vegetative nature but owing to their lack of chlorophyll, they were classified differently. According to a landmark paper in 1991, approximately 1.5 million existing fungi and about 300 are infectious to their hosts (Etxebeste et al., 2019). The Structure of Fungi include:

- They are made up of filaments except for yeast cells.

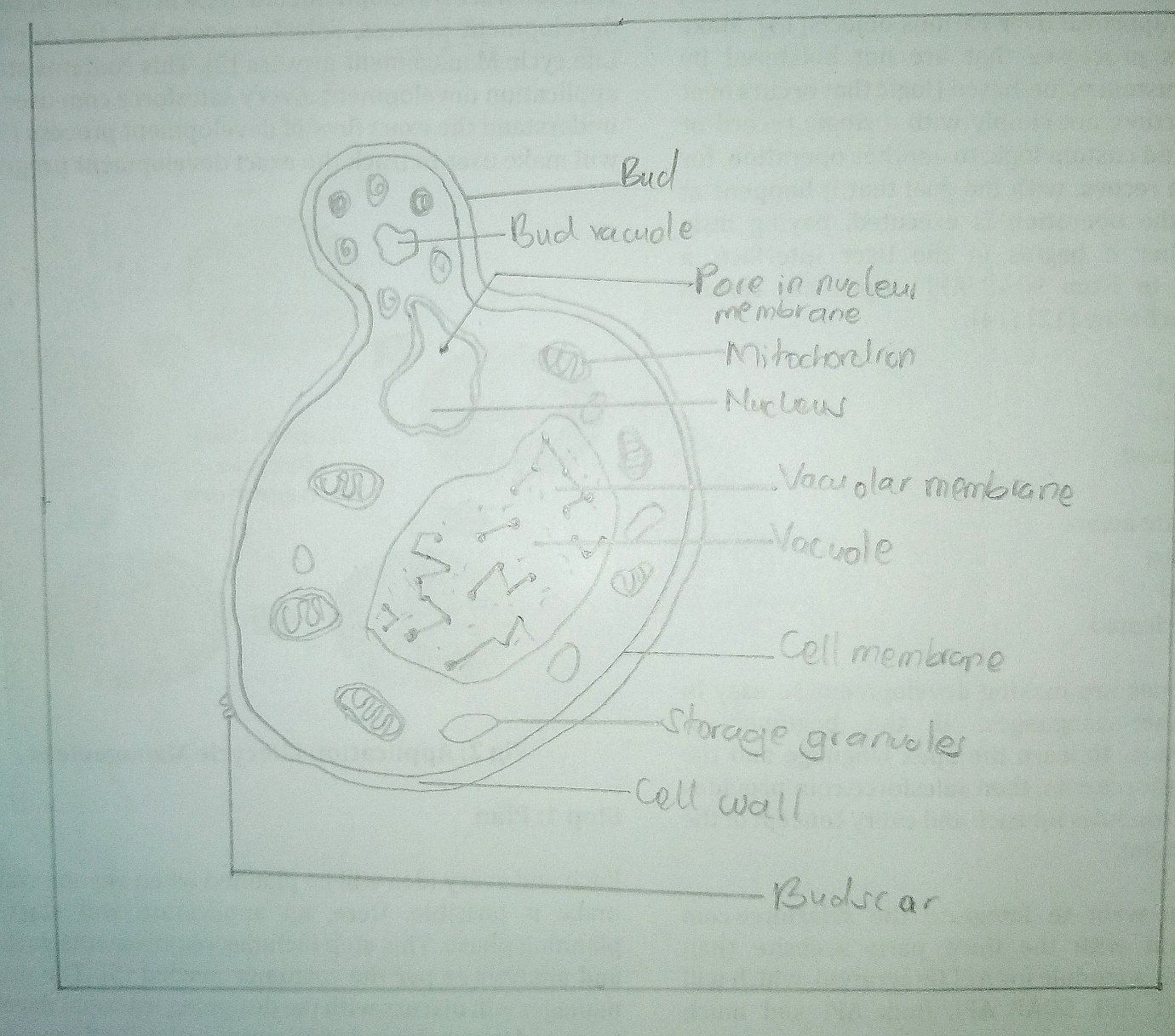

- Some are single-celled (unicellular), such as yeast, and others are multicellular organisms.

- Cell walls of this kingdom’s organisms are made up of chitin, a fibrous matter made up of polysaccharides and is majorly found in arthropods of kingdom Animalia.

- They contain protoplasts differentiated into other cell organelles such as cytoplasm, cell membranes, and the nucleus.

- Their cell organelles are bound by membranes hence the name eukaryotic.

- The fungi nucleus is tiny and precise and is surrounded by chromatid threads. A nuclear membrane surrounds it.

- They are characterized by long threadlike structures called hyphae. These hyphae combine to form a mesh-like structure called the mycelium.

Characteristics of Fungi

- Fungi do not have vascular organs; these are the xylem and phloem.

- They are non-motile and heterotrophic (they depend on a host- plant or animal- for energy)

- They are eukaryotic (nucleus and other organelles are membrane-bound)

- They reproduce asexually. However, some fungi produce pheromones for sexual reproduction to take place.

- They produce through spores.

- They display alteration of generations in their reproduction.

- Fungi store food in the form of starch.

- They do not have chlorophyll; therefore, they are incapable of photosynthesis.

- Biosynthesis of chitin occurs in fungi since it is stored in the cell walls.

- Fungi do not have an embryonic stage since they reproduce asexually.

Fungi are classified into five phyla depending on their types of reproduction. That is:

- Zygomycota (the zygote fungi): Their sexual spores are identified as zygospores and asexual sporangiospores. They reproduce by the fusion of two different cells.

- Basidiomycota (the club fungi): Their sexual reproduction occurs utilizing basidiospores and asexual by budding, conidia, and fragmentation.

- Ascomycota (the sac fungi): They reproduce sexually through ascospores and asexually by conidiospores.

- Chytridiomycota: They reproduce sexually by means through the fusion of isogametes and asexually through zoospores.

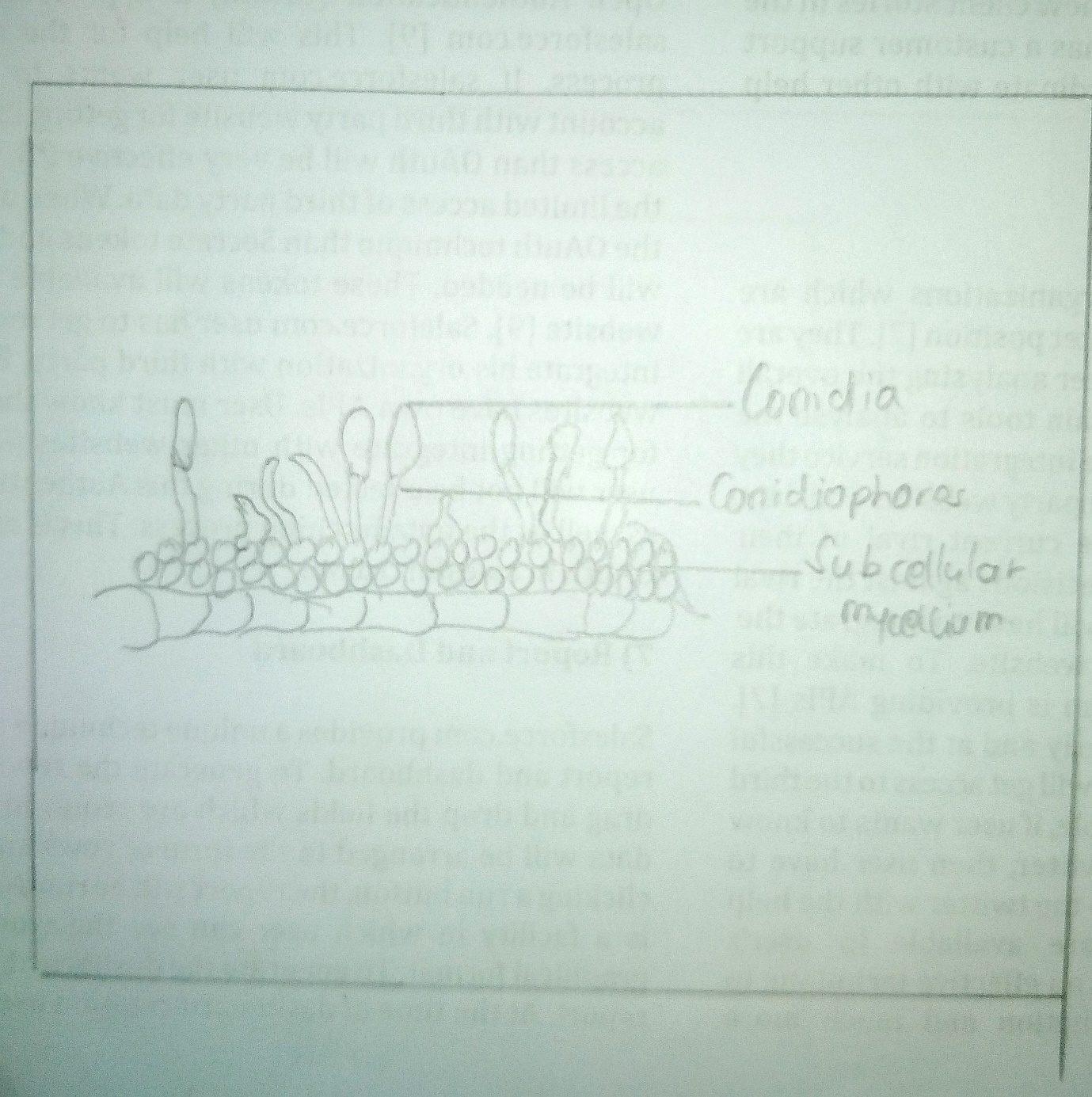

- Deuteromycota (the imperfect fungi): They are irregular in their reproduction. However, they all reproduce asexually through conidia.

This assignment focuses on the diagrammatic representation of different living organisms in kingdom Fungi, pointing out some of their prominent features.

Lichens

They are a complex type of vegetative organisms made up of both fungi and algae. However, the fungal characteristics are dominant hence its classification under kingdom Fungi. They are classified into three depending on their growth form (the thallus and apothecia), that is:

Crustose

These Lichens are flat and crusty. They are brightly colored and are tightly bound to their hosts. Their apothecia are on the upper surface.

Foliose

They are leaf-like lichens since their thalli are highly branched and folded in the form of leaves.

Fruticose

They are highly branched and erect, forming a shrub-like appearance. The thallus is highly vegetative, and its color is highly dependent on the amount of light it receives. It is made up of stems and leaves that are not real.

Examples of Lichens

Lobaria sp. (The lung lichen)

Belongs to the phylum Foliose.

Letharia sp. (The wolf lichen)

It belongs to the phylum Fruticose.

Romania sp. (The cartilage lichen)

It belongs to the phylum Fruticose.

The British Soldier Lichen

Zygomycota (The zygote fungi)

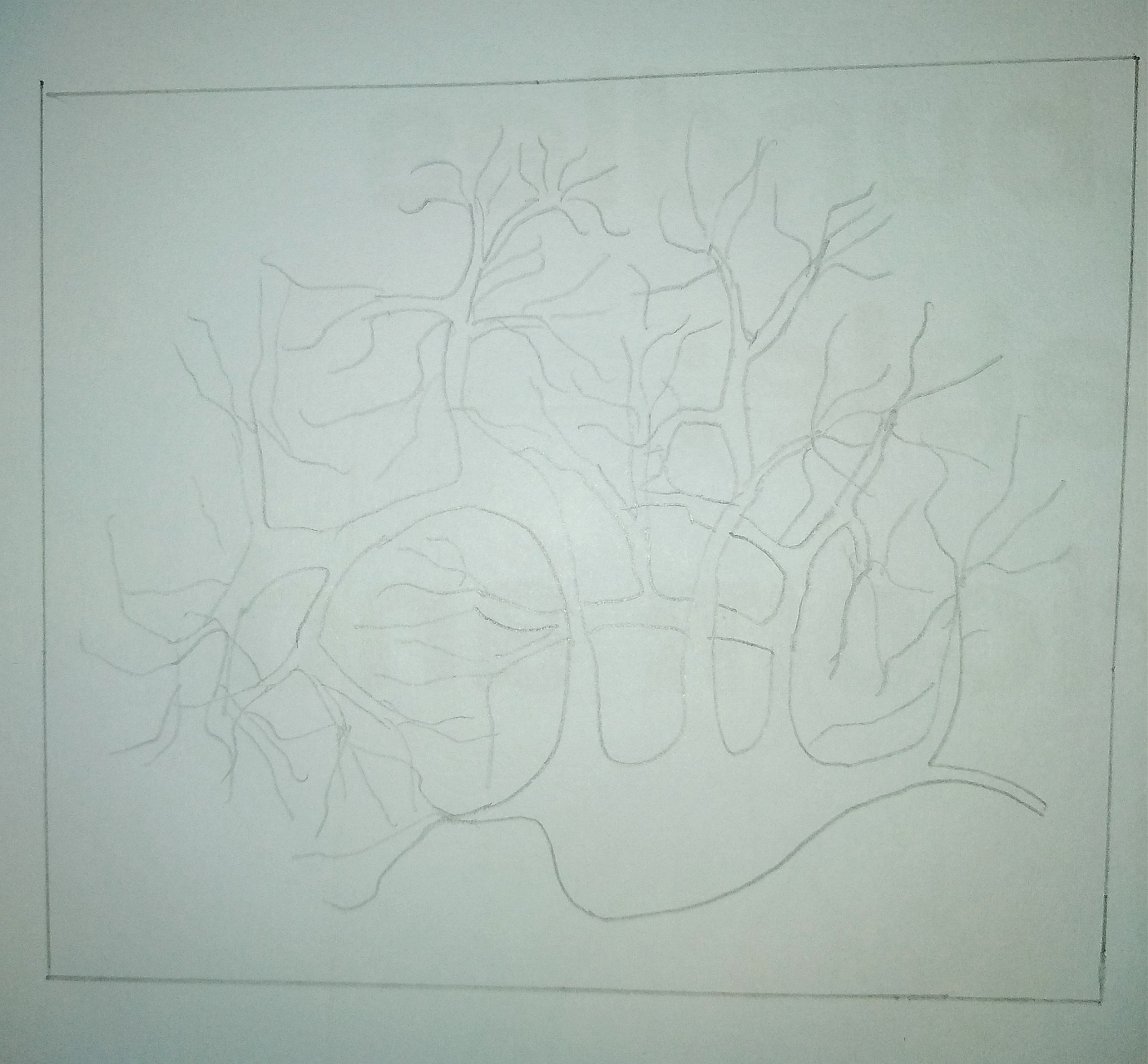

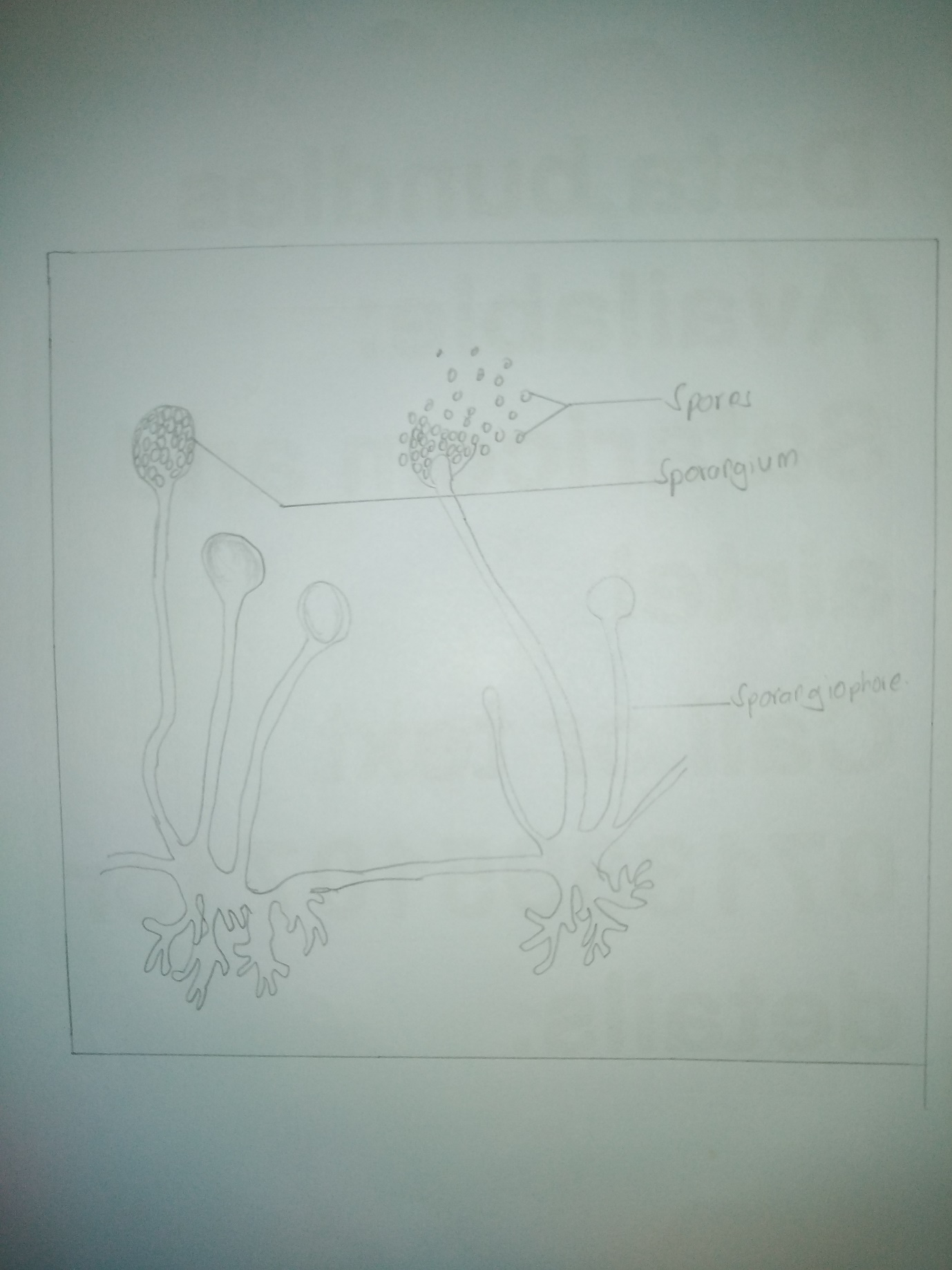

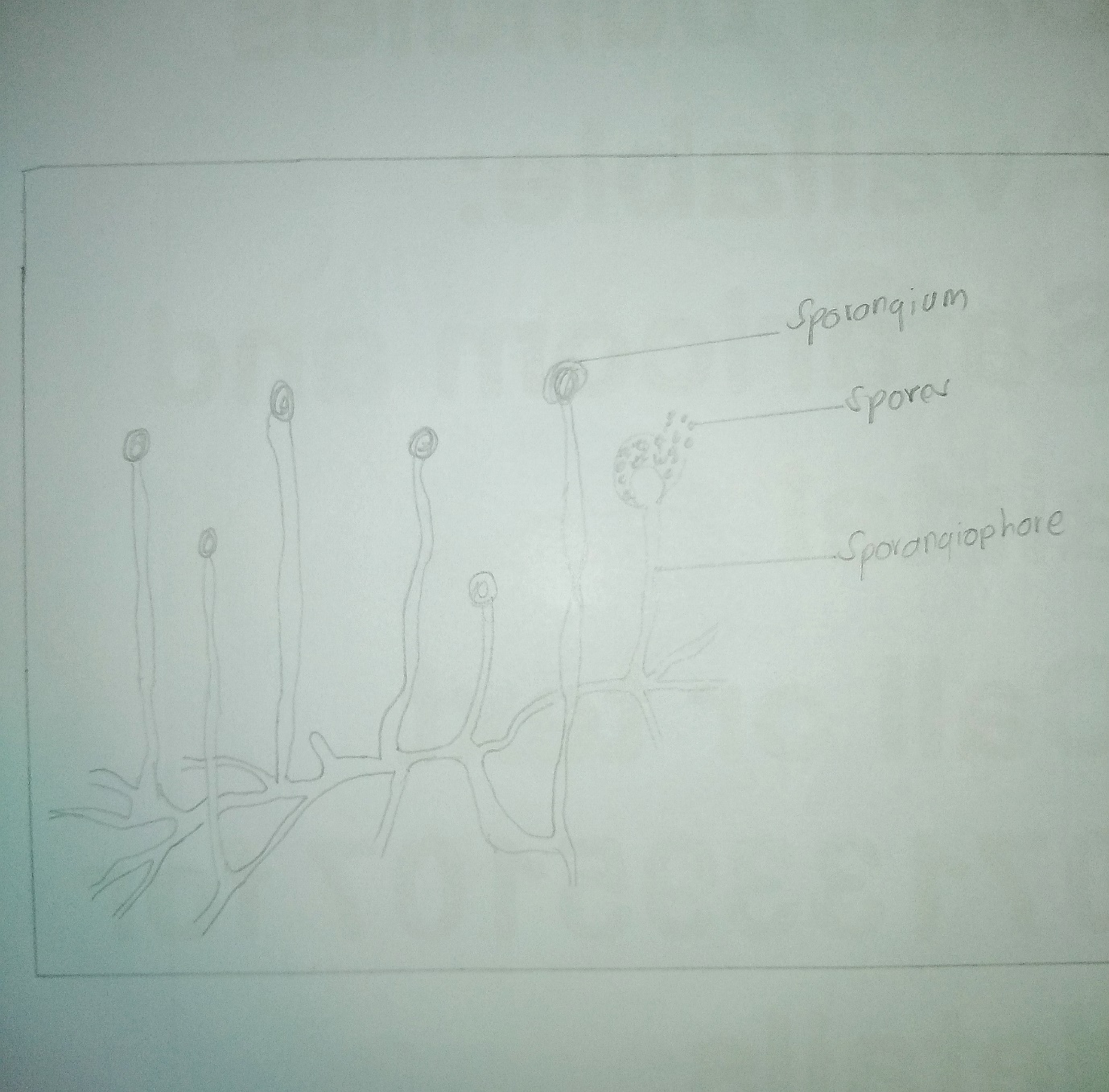

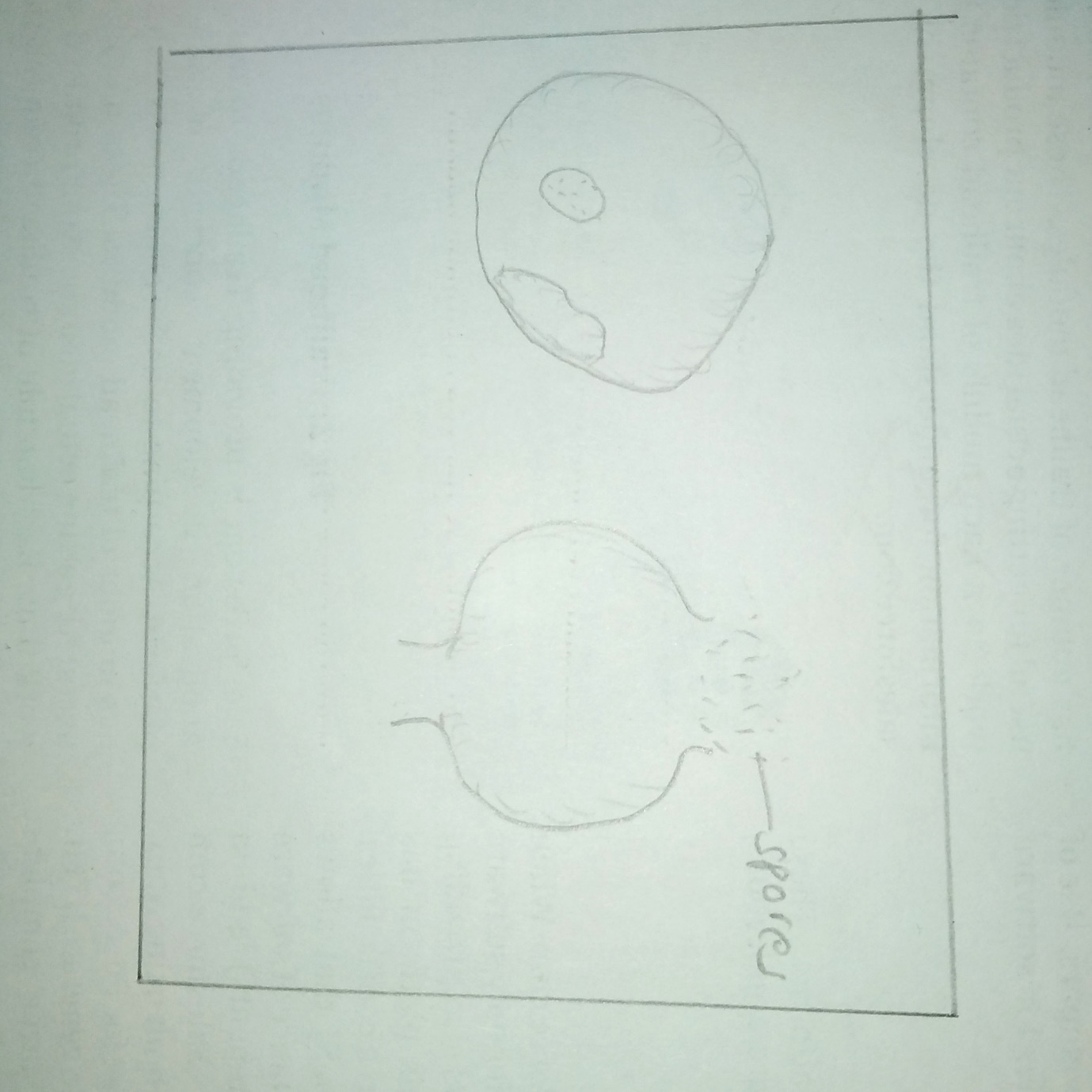

Rhizopus

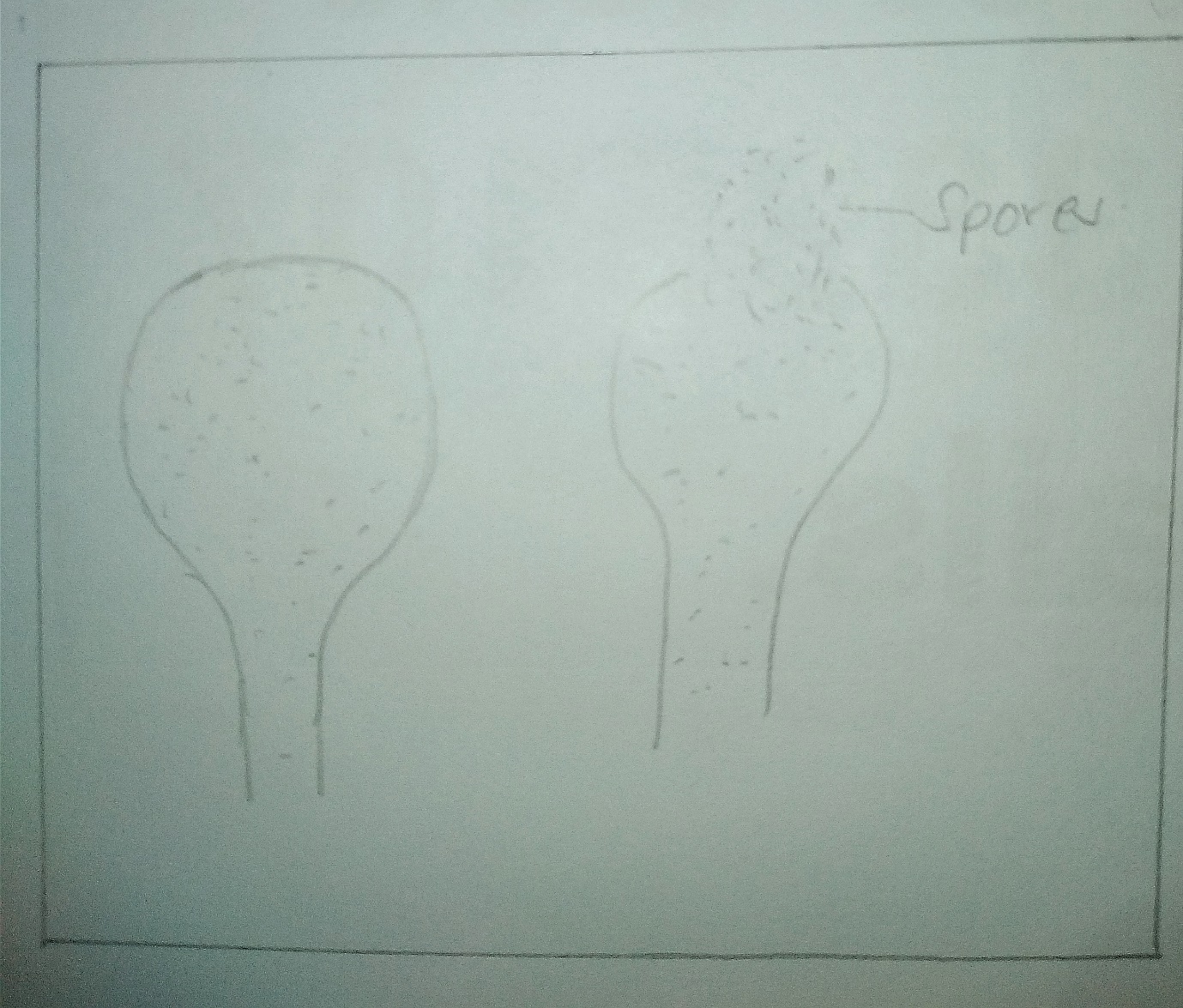

Examples include the black bread mold. They are characterized by rhizoids which they use to attach to their host surfaces. Reproduce employing zygospores. Figure 2.1 shows their sporangia, sporangiospores, and spores (zygospores).

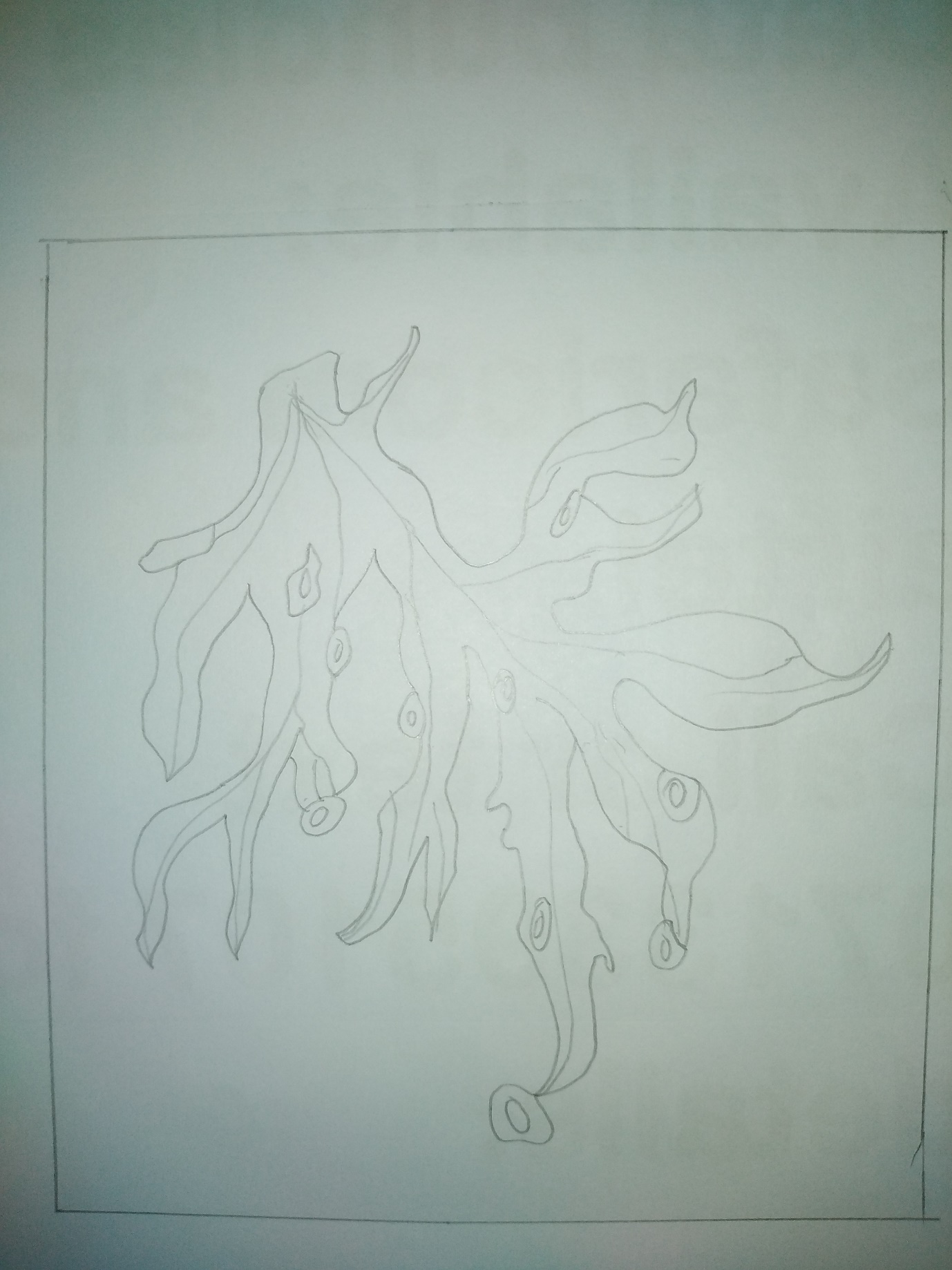

Mucor

Examples include the mold of the soil and fruits. It is characterized by a mass of delicate cotton-like threads called hypha. Figure 2.2 represents its labeled diagram.

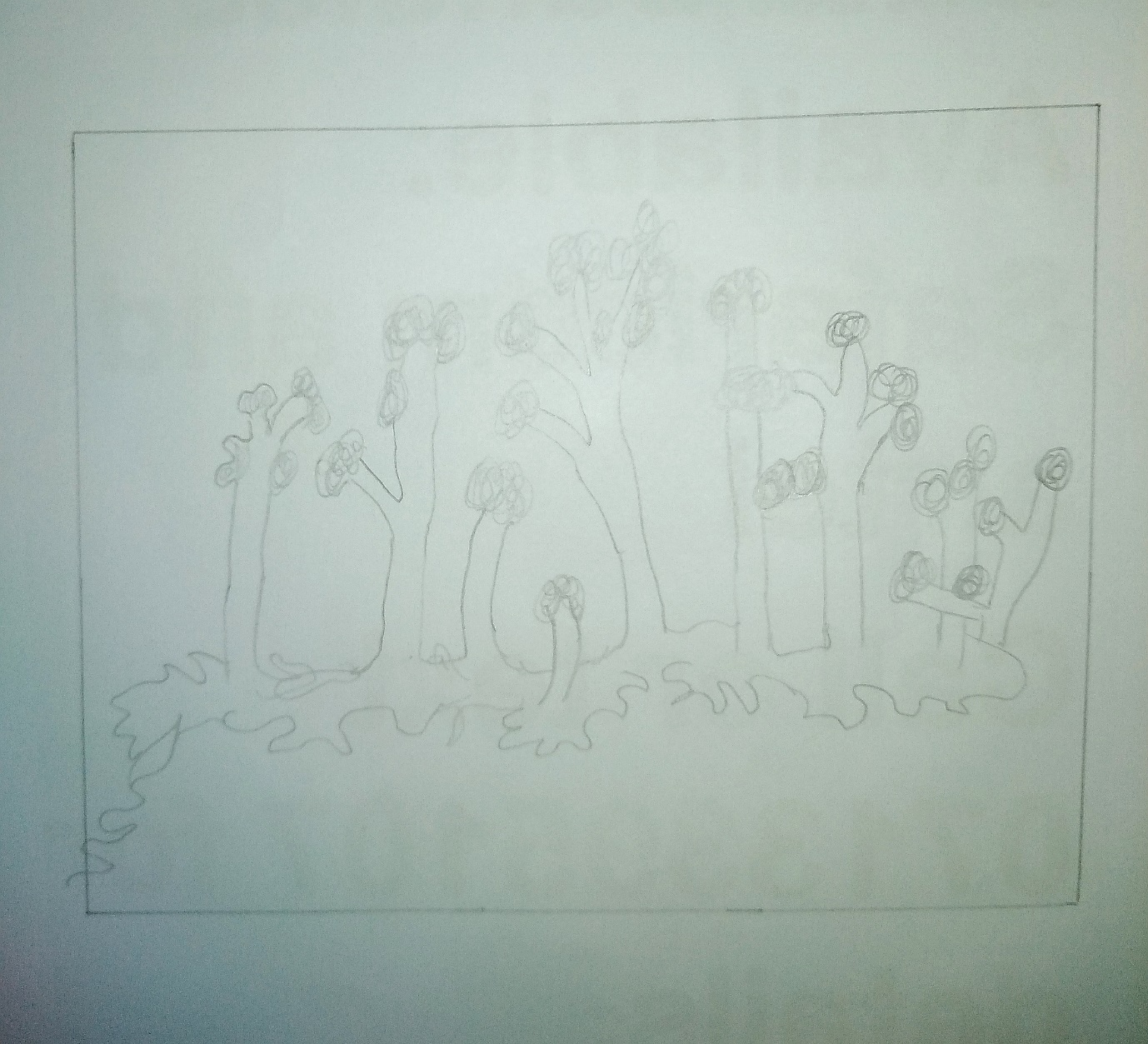

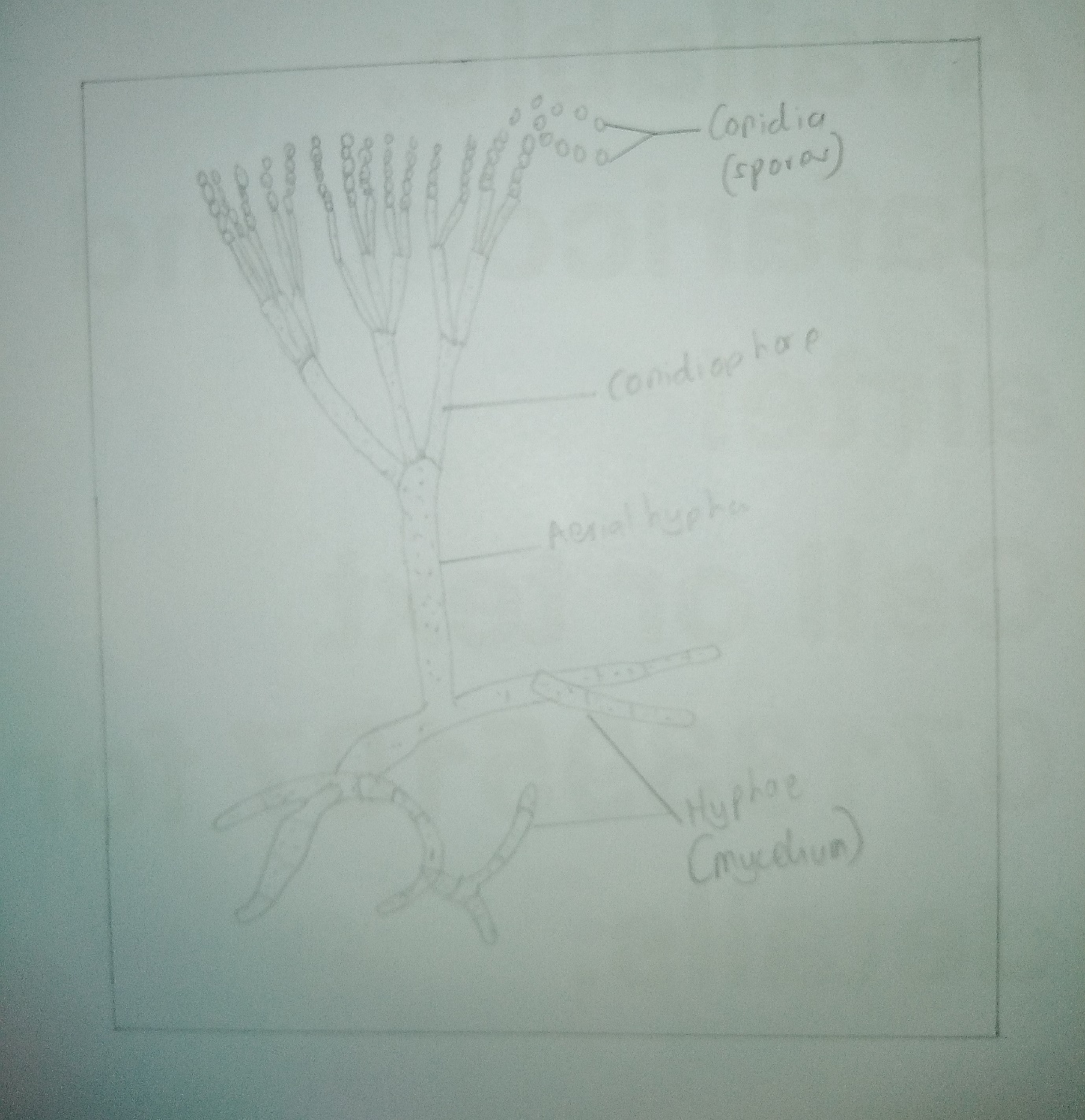

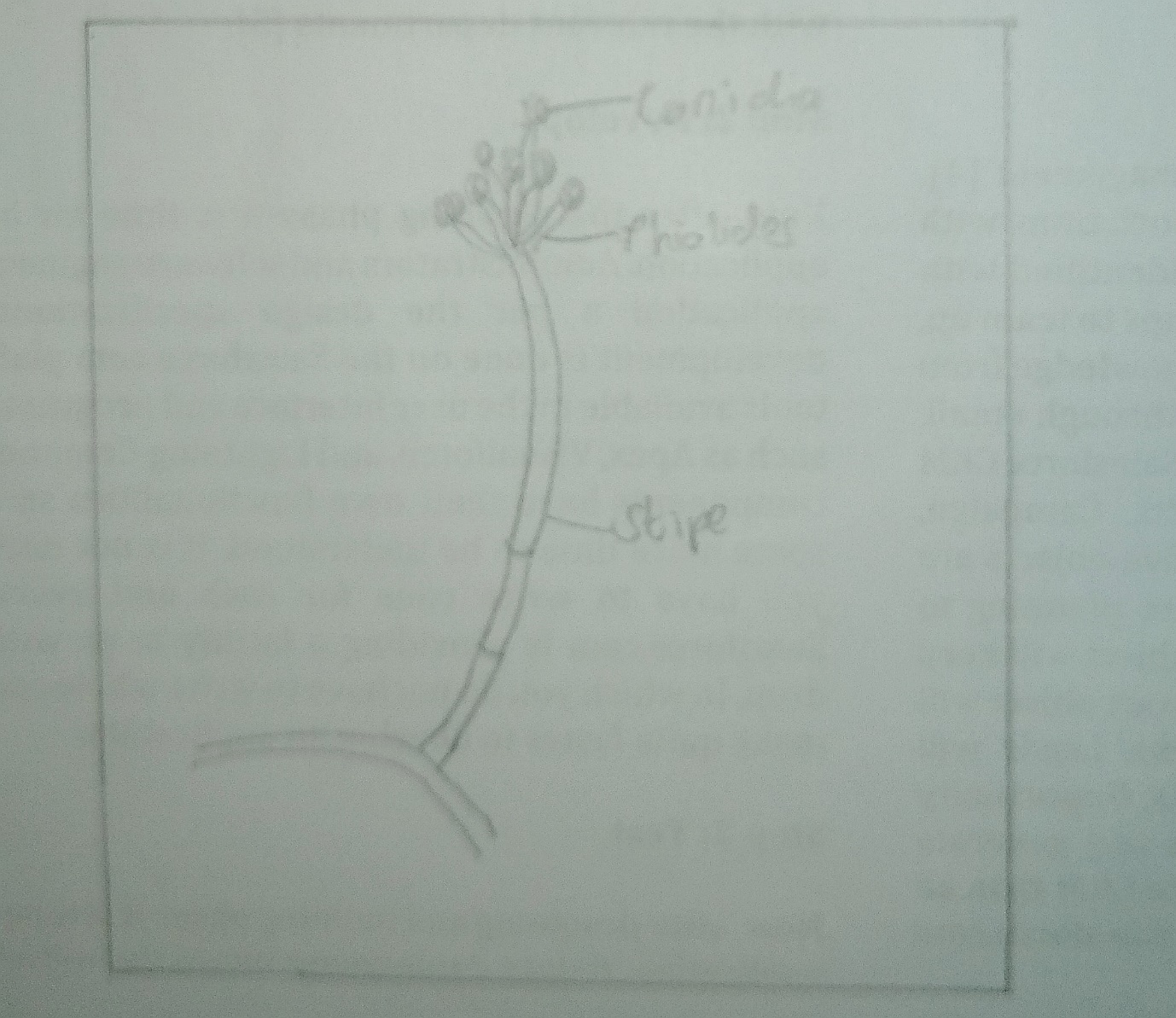

Aspergillus

It has a filamentous structure with chains of conidia at the end of the filaments. Figure 2.3 represents a labeled diagram.

Basidiomycota (The club Fungi)

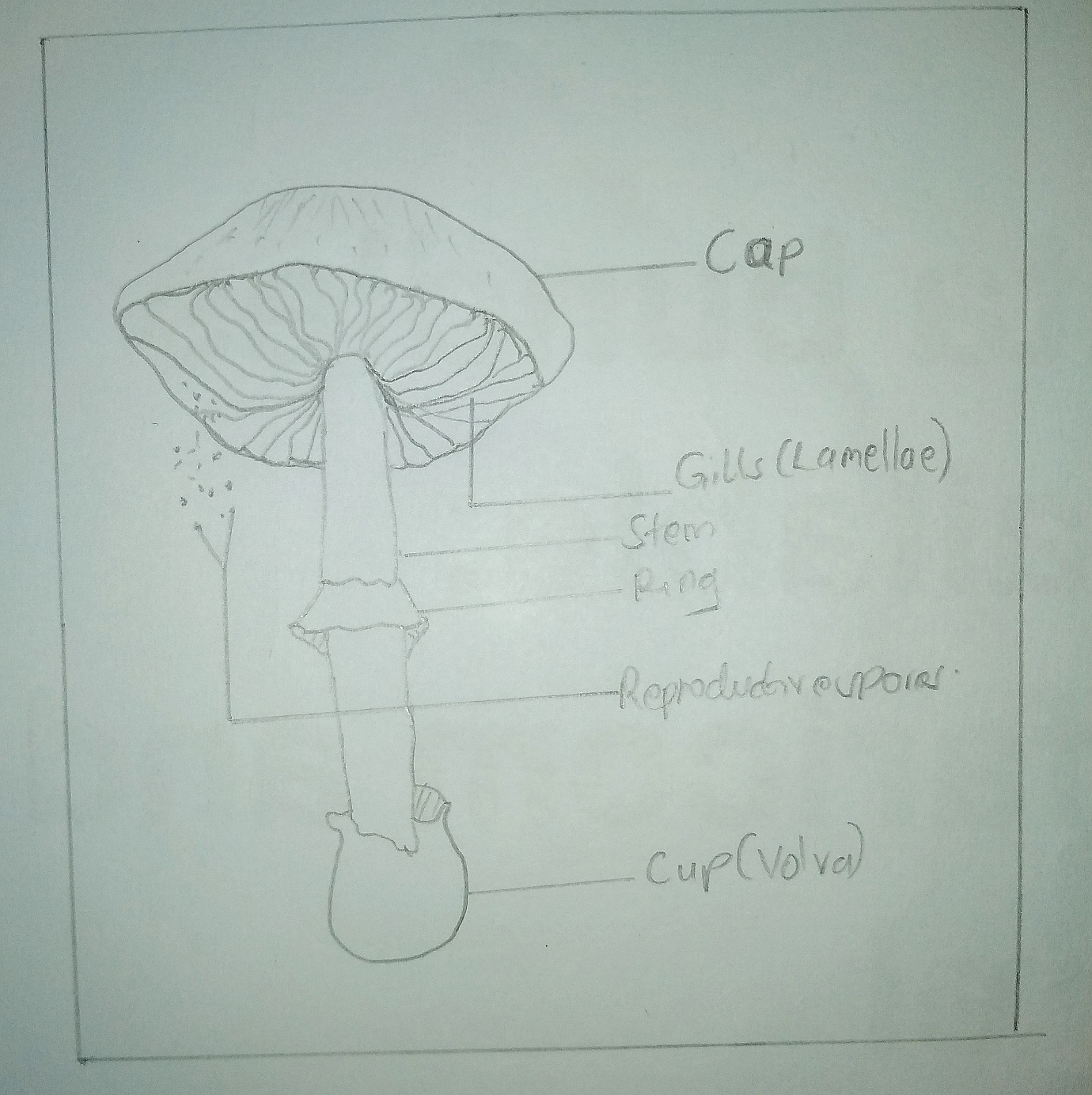

Under the light microscope, these organisms’ fruiting organs appear large and club-like. For instance, some of them, the edible mushroom, have gills through which spores are produced for reproduction. They include:

Ustilago sp. (smut)

They grow on parts of organisms from kingdom Plantae, such as the fruit on Zea Mays.

Clavaria sp. (Coral Fungi)

They are also called fairy fingers. They are made of wide and thick fruiting parts and broad hyphae.

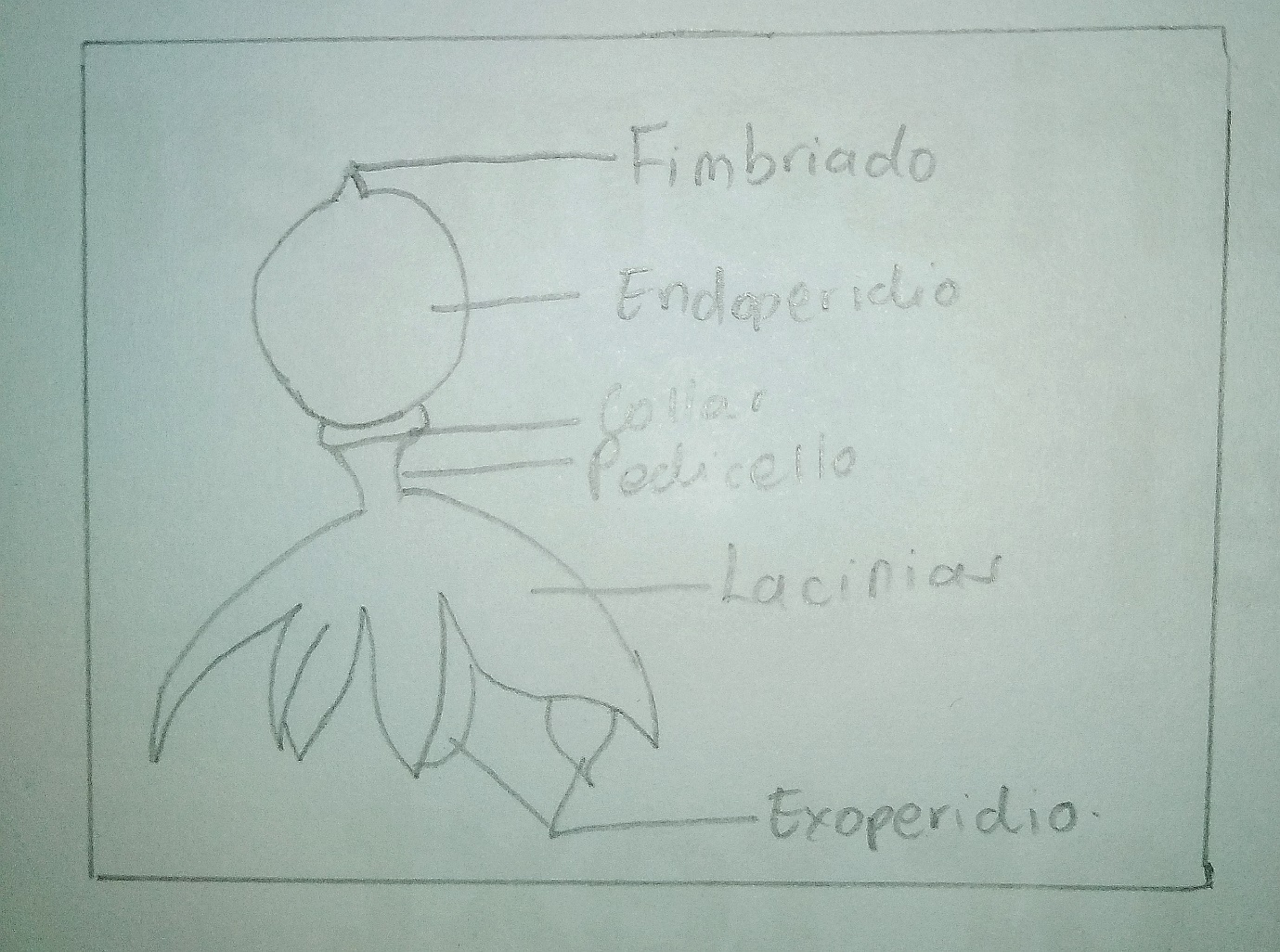

Geaaster (Earthstars)

Lycoperdon sp. (puff balls)

Common edible mushroom

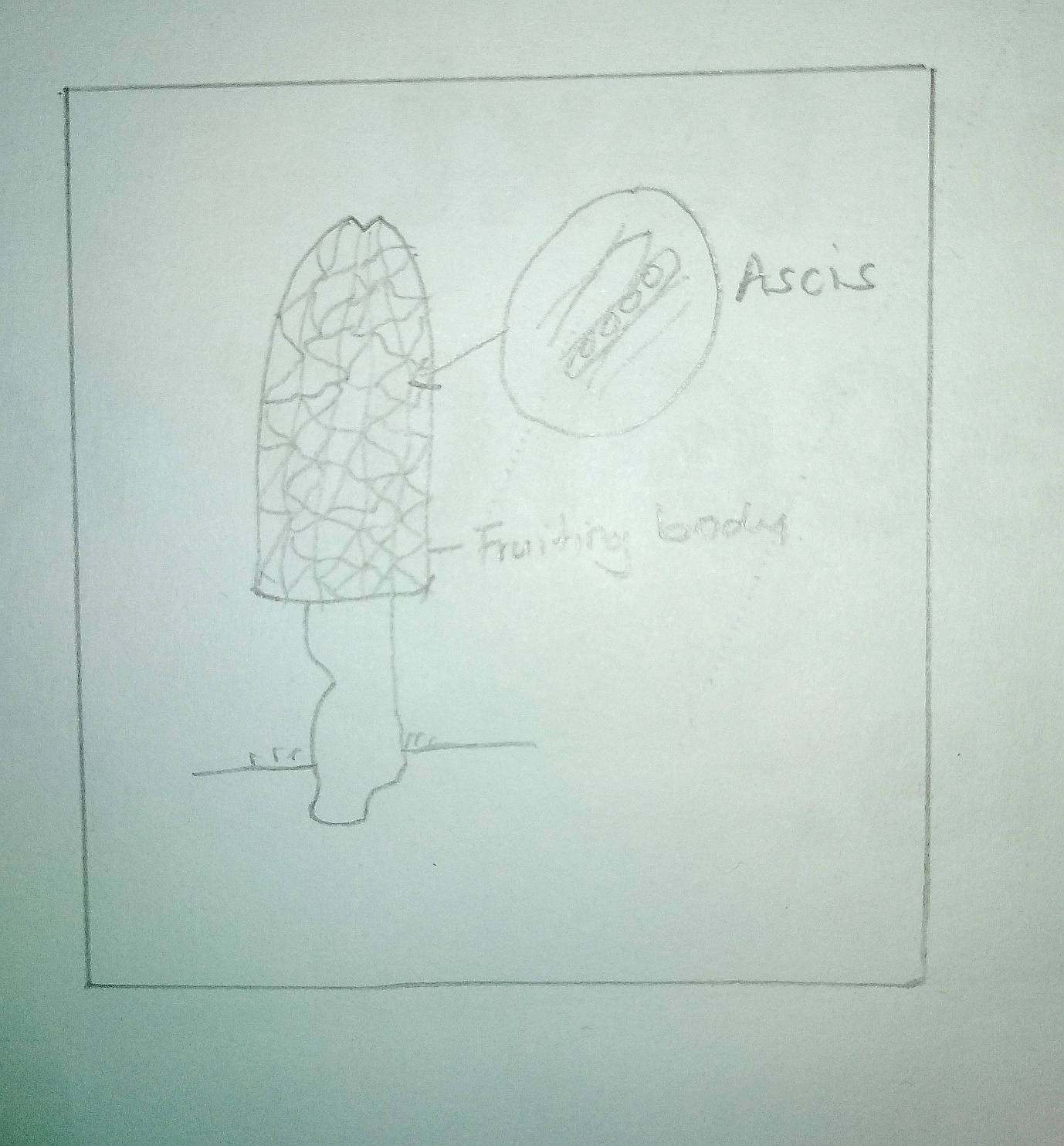

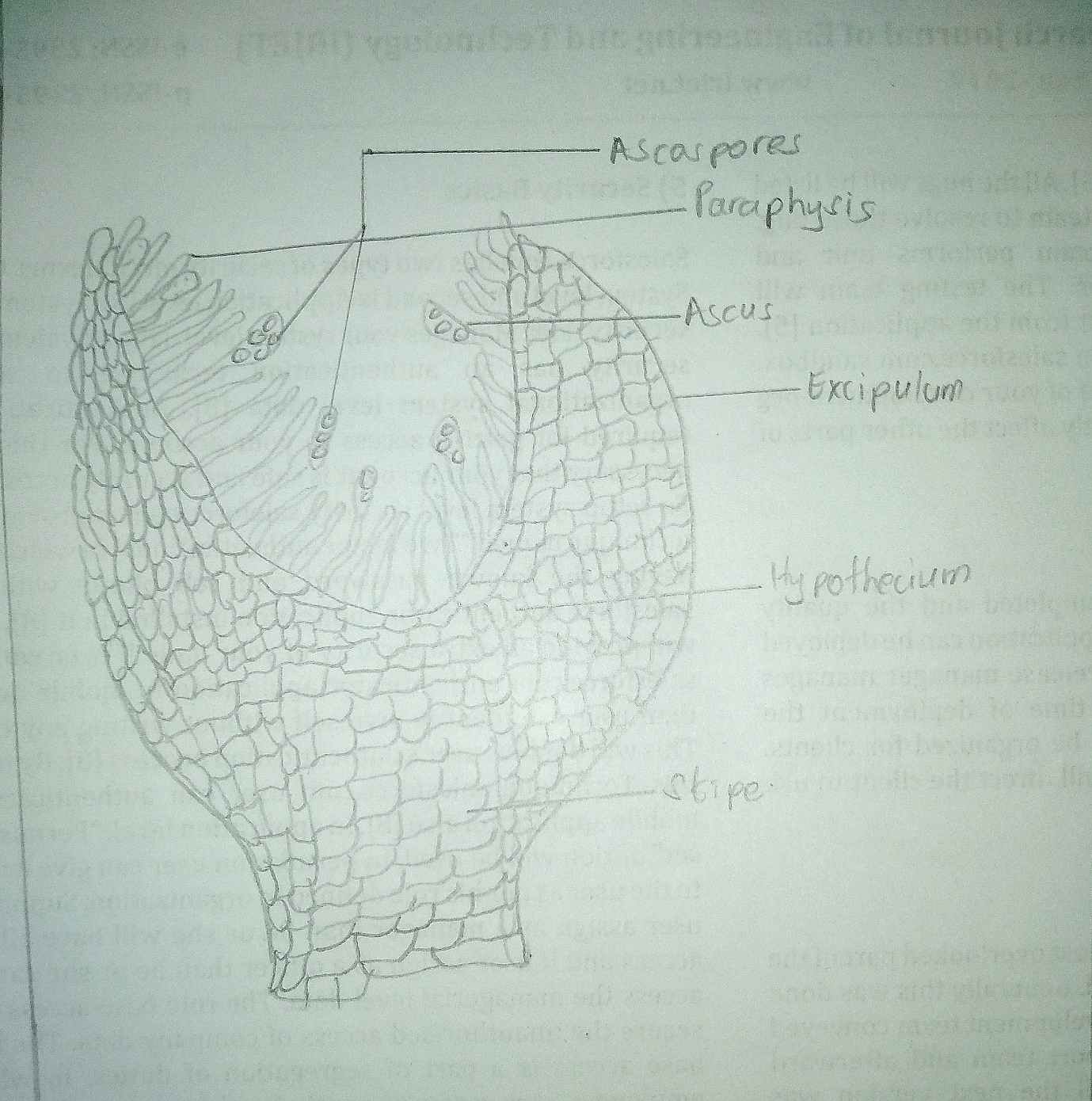

Ascomycota (The sac-like fungi)

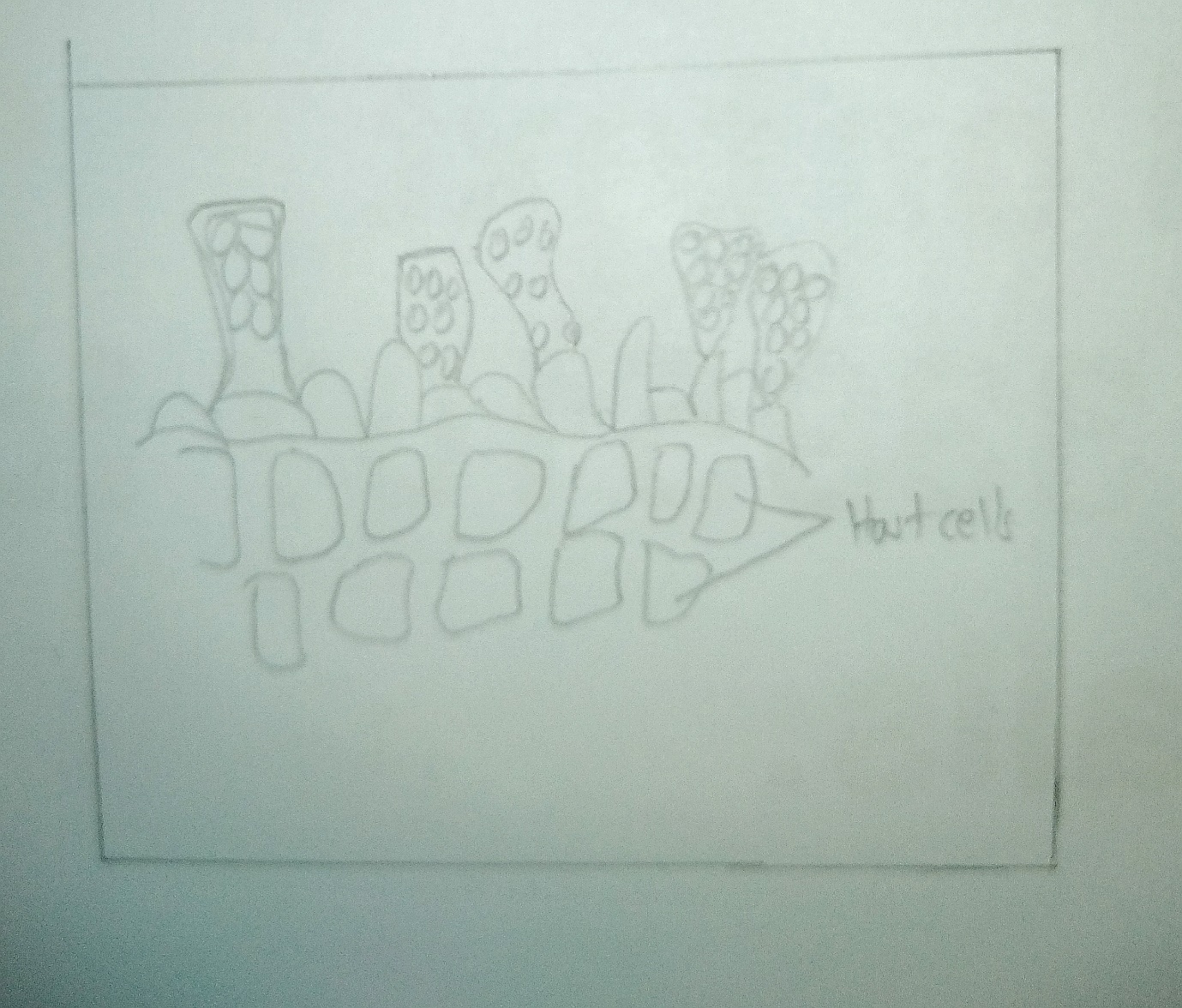

They are characterized by asci development, which is sac-like and is used to store haploid ascospores. Those that are filamentous have hyphae that are divided to form septa.

Taphrina sp

Morchella sp

Peziza sp

Venturilla sp

Yeast

Penicillin sp

Interesting species

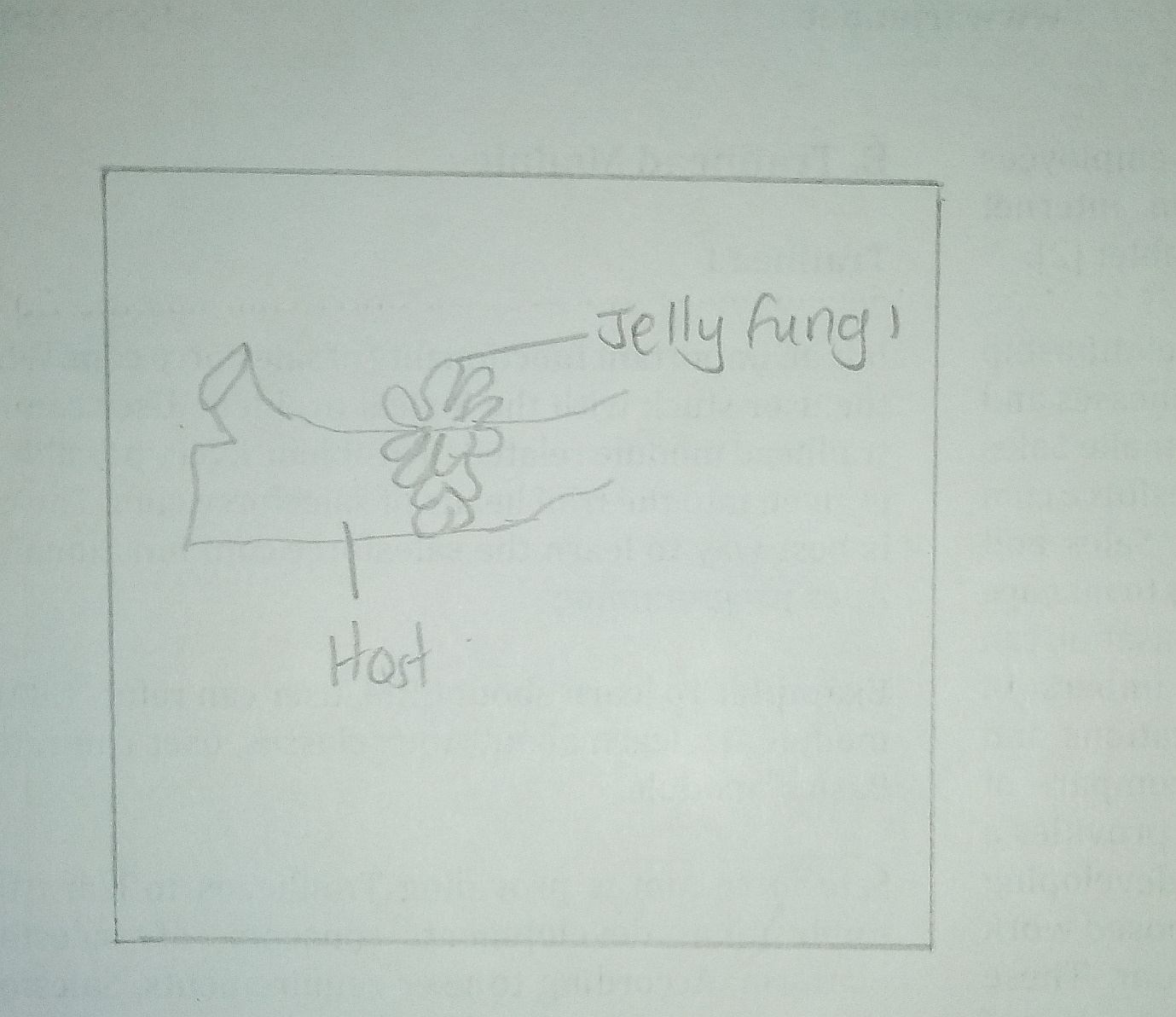

Jelly Fungi

Giant puffballs

Reference

Etxebeste, O., Otamendi, A., Garzia, A., Espeso, E. A., & Cortese, M. S. (2019). Rewiring of transcriptional networks as a major event leading to the diversity of asexual multicellularity in fungi. Critical reviews in microbiology, 45(5-6), 548-563.