Outline of the Subject

Introduction

Many companies, all over the world pay a part of their earnings, as cash dividends. Corporations view the dividend decision as quite important, because it determines the amount of funds should flow to the investors and the amount of funds to be retained by the firm for reinvestment. Dividend policy of a company can also provide information to the stockholder concerning the performance of the firm. However, dividends cannot be viewed in isolation.

Many companies currently utilize a higher percentage of their net income to share repurchases as well, and this percentage has increased over the period. Therefore, dividends and repurchases must be seen as alternative payouts competing for corporate cash flows. This paper deals with the practical aspects of dividends, taxation considerations, its impact on the stock prices and other relevant issues analyzed in past research.

Dividend – an Overview

The term “dividend” usually refers to a cash distribution of earnings by a company and dividend is distributed out of current or accumulated earnings. If a distribution is made from sources other than the current or accumulated earnings, the term “distribution” is used to denote such payouts. The most common type of dividend is in the form of cash dividend. Public companies usually pay regular cash dividends up to four times in a year. Making a cash dividend payment reduces the the corporate cash and retained earnings shown in the balance sheet. Another type of dividend is paid out in the form of shares of stock.

This dividend is referred to as a stock dividend. It cannot be considered as a true dividend as no cash leaves the firm. The decision to pay a dividend rests in the hands of the board of directors of the corporation. A dividend is distributable to shareholders of record on a specific date. When a dividend is declared, it becomes the liability of the firm and it cannot be easily rescinded by the corporation (Ross, Westerfield, & Jaffe, 2002). The amount of dividend is expressed as dollars per share (dividend per share), as percentage of the market price (dividend yield) or as a percentage of earnings per share (dividend payout).

There are several factors, which justify the payment of dividends by the companies. For instance, cash dividend payments underscore a good performance by the company and provide support to stock price. Dividends may attract institutional investors who would like to have some return in the form of dividends. A mix of individual and institutional investors would enable the firm to raise the capital requires at comparatively lower cost as it can reach a wider market. Stock prices usually increase with the declaration of a new or increased dividend. Dividends absorb excess cash flow and may reduce agency costs that arise from conflict between the management and shareholders (Ross, Westerfield, & Jaffe, 2002).

However, there are some issues, which discourage the payment of dividends. Since dividends are taxed as ordinary income, normally this form of payouts by the company is discouraged. Dividends can reduce the internal sources of financing. Dividends may force the firm to forego projects with positive net present values (NPVs) or rely on costly external debt financing. Once established dividend cuts are impossible to make without a consequent reduction in the stock price of the firm.

Dividend Policy

The dividend policy of a company normally depends on the cash requirements of the company for investing in different new projects or for expanding the existing business opportunities. The number of projects with positive net present values determines the dividend payout policy of the company. Firms with many projects with positive net present value relative to available cash flow should adopt a low dividend payout ratio and conversely, firms with a lesser number of positive NPVs relative to available cash flows would follow a liberal dividend payout policy. Since consistency in the dividend payouts over years have certain advantages, companies normally avoid changing the dividend payout policies (Ross, Westerfield, & Jaffe, 2002).

However, there is no formula for calculating the optimal dividend-to-earnings ratio. In addition, there is no formula for determining the optimal mix between repurchases and cash dividends. It can be argued that because of tax implications firms should always substitute stock repurchases in place of dividends. However, while the volume of repurchases has greatly increased over time, dividends do not appear to be on the way out.

The following sections of the paper present a review of the related literature and the empirical results of the studies that enrich the knowledge on the subject of dividend policy.

Review of the Related Literature

The objective of this chapter is to provide a deeper insight into various aspects of dividend payments by companies by reviewing past research on the subject.

Introduction

Miller & Modigliani, (1961) provided the initial thinking on the modern theory of dividend policy. They postulated that since the investment policy of any firm is set ahead of time, the dividend policy is irrelevant. Studies by Allen & Michaely, (2002) have materials to offer extensive insight into the literature relating to dividend policy. Agency theory is one of the theories developed to describe the relationship between ownership and control of a firm and according to this theory, the purpose of dividend policy is to minimize agency costs representing costs arising out of the divergence of ownership and control.

Grossman & Hart, (1982), Easterbrook, (1984) and Jensen, (1986) are some of the earlier scholars who contributed to the development of theoretical frameworks on dividend policy. This review attempts to present an analysis of the views of different scholars on the impact of dividend policy on agency costs, shareholders’ rights, stock prices, and several other associated issues relative to dividend policy.

Agency Costs

The article by Jensen (1986) revolves around the agency theory, which states that dividend payouts to shareholders will reduce the financial resources available at the disposal of the managers, and this will reduce the power of the managers. This necessitates the managers to watch the capital market closely as the firm may need new capital now and then. On the other hand financing, the new projects from the available internal cash accruals of the company would avoid this monitoring of the capital markets by the managers. It also reduces the uncertainty on the costs associated with the raising of funds from external sources.

The article describes the free cash flow as one, which is available in excess of the funds required to fund all new projects having positive NPVs. Jensen (1986) further states that the conflicts of interests between managers and shareholders intensify especially in the circumstances where the firm is in a position to generate substantial cash flows. Agency theory deals with the ways of motivating the managers to flush out the excess cash flow rather than investing it at below the cost of capital or wasting it on any inefficient operations of the firm.

Managers always find it advantageous to see that the firms grow beyond optimal size as such growth gives them enormous powers and increases the resources under their control. It has also a nexus with the enhanced compensation of the managers as growth in sales leads to enhanced compensation for managers (Murphy, 1985).

Jensen’s article develops a theory to deal with the benefits of debt on reducing agency costs (costs arising out of the divergence of ownership and control) pertaining to free cash flows, the manner in which debt can substitute dividends, and the reasons as to why diversification programs are more likely to fail financially than takeovers or expansions. It also attempts to explain the reasons for the abnormal performance of the stocks of bidders and some targets prior to the takeover.

Article by Easterbrook (1984) also deals with the agency-cost explanation of dividends. Easterbrook (1984) states the purpose of any dividend or other corporate policy is to minimize the sum of capital costs, agency costs, and taxation costs. The article attempts to find out whether dividends payout can be used as an instrument in aligning the interests of the managers with that of the shareholders.

One of the forms of agency costs is identified as the cost of monitoring of managers and this cost is found to be expensive for the individual shareholders. However, the individual shareholder, only in proportion to his/her, would gain any saving in these costs shareholding. Another source of agency costs Easterbrook (1984) discusses is the risk aversion on the part of the managers (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Managers tend to tie up a substantial value of their personal wealth in the form of stocks in their respective companies and in case, if the company does not do well financially or becomes bankrupt the managers would lose their jobs as well as a major portion of the personal wealth tied up with the firm. Therefore, the managers would choose projects, which are rather safe even though they have a lower expected return than riskier ventures.

Therefore, the question is whether the distribution of the available cash resources with the company as dividends would reduce this agency cost. Managers can use a dividend policy to change the risk of the firm by altering the debt-equity ratio. The lower the debt-equity ratio the lower the risk becomes for the firm. Therefore, managers by adopting a stringent dividend policy may issue debts first, and then finance the projects by retained earnings reducing the distribution of surplus to the shareholders by way of dividends. Shareholders on the other hand would like to have enhanced dividends and would induce the managers to undertake more risks so that they do not part with the wealth to the bondholders (by issuing of debts by the managers).

Dividend and Share Prices

Changes in dividend policies of corporations do have an effect on their share prices in the stock market. The article by Michaely, Thaler, and Womack, (1995) investigates the reactions of the stock market in respect of the prices of shares of firms resorting to the initiation and omission of cash dividend payments (Healy & Palepu, 1988; Asquith & Mullins, 1983). It is the normal presumption that the prices of a firm’s stock frequently rise when either its current dividend is increased or stock repurchase is announced. Conversely, the price of a firm’s stock can fall significantly when its dividend is cut. This implies information content in payouts.

This study by Michaely et al (1995) finds that the magnitude of short-run price reactions of stocks is greater for the omission of dividend payouts. On the other hand, the price reactions for dividend initiation decisions are not that large as compared to the omissions. Similarly in the year following the announcements the prices continue to traverse in the same direction as that of the last year and in this case also the price changes following the omissions are sharper and more robust. The study based on the results of previous research attributes three reasons for expecting substantial excess returns in the year following the dividend announcements.

They are:

- Post-earnings announcement drift (Bernard & Thomas, 1989) which implies an underreaction of the market. In this case, it is postulated that since the initial reaction of the market for omission or initiation announcements is insufficient there will be subsequent drifts upwards or downwards depending on whether the firm made the announcement for initiation or omission respectively.

- Firms that show extreme rise or reduction over the last 3 to 5 years tend to display excess reactions, following the initiation or omission decisions of the firms (DeBondt & Thaler, 1985).

- The third reason is that any action in the direction of omission or initiation would have an impact on the composition of the stockholders owning the company. According to Black & Scholes, (1974) such changes can be expected in the type of stockholders owning the company because some classes of investors may not prefer to have cash dividends for taxation reasons, while others would prefer to have cash dividend payments (Shefrin & Statman, 1984). This is known as the “clientele effect”.

Frank and Jagannathan, (1998) examine the drop in stock prices in relation to the value of dividends. Normally it is theorized that stock prices drop by less than the value of the dividends and this drop occurs on ex-dividend dates. The effect has been attributed to the tax clientele effect, implying that such reduction in stock prices would follow in a market where there are regulations covering dividend taxes and capital gains. Elton & Gruber, (1970) have identified tax considerations on dividends affecting the share price movements. This study with the evidence from the Hong Kong stock market where there is no regulation on dividends or capital gains proves the theory that stock prices fall below the value of the dividends.

Therefore, the authors conclude that it is difficult to interpret the relationship between the amount of the dividend and the average ex-dividend day price drop. The possible reasons identified by Frank & Jagannathan (1998) are that there is a tendency for the investors to place a buy order as a group after the stock goes ex-dividend and to place group sell orders when the shares go cum-dividend. However, in the data analyzed there is no probability of these actions have taken place nor the bid-ask spreads have been observed.

Shiller, (1981) observes that the measures of stock price volatility during the past periods seem to be at a higher level of 5 to 13 times too high. This increase is attributable to the new information on future real dividends. The study witnesses a dramatic failure of the efficient markets model with the disproportionate increase in stock price volatility and the author opines that it would seem impossible to attribute the failure to issues like data errors, price index problems, or changes in taxation considerations.

Dividend versus Stock Repurchases

Corporate payout policy generally suggests that dividends and stock repurchases are equivalent ways of paying out cash flows by the firms (Brealey & Myers, 1996). Firms normally view dividends as a commitment to their stockholders and are quite hesitant to reduce an existing dividend. Repurchases do not represent a similar commitment. Thus, a firm with a permanent increase in cash flow is likely to increase its dividend. Conversely, a firm whose cash flow increases only temporarily is likely to repurchase shares of stock. This is the finding from the study conducted by Jagannathan, et al, (2000). The following table illustrates the volume of repurchases against dividends paid out during the years 1985-1996.

Table: Payout Measures and Payout Techniques.

The authors observe that stock repurchases and dividends are used at different times from one another by different firms. Stock purchases have been found to be very pro-cyclical. On the other hand, dividends appear to be increasing steadily over time. Repurchasing firms are found to have more volatile cash flows and distribution. The other finding of the study is that the firms tend to repurchase stocks following poor stock market performance and they tend to declare and pay higher dividends when the stock markets perform better. The flexibility inherent in the repurchase programs is one of the main reasons for being preferred to payment of cash dividends.

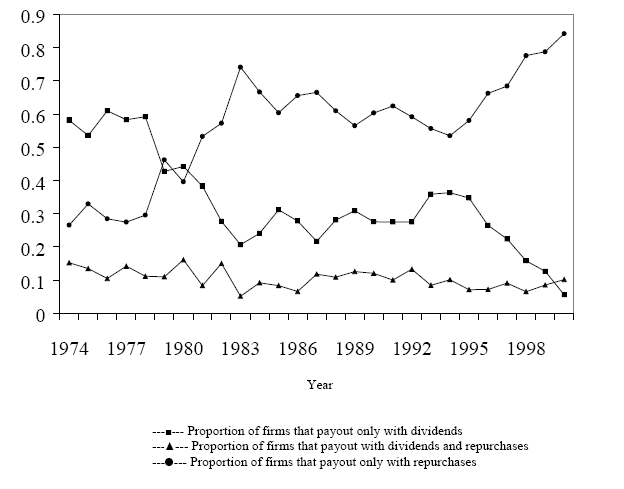

The finding of Jagannathan, et al, (2000) has been substantiated by Grullon & Michaely, (2002). Based on their study they observe that apart from becoming an important form of payout for the corporations in the United States, firms tend to finance the repurchases out of funds that otherwise would have been available for payment of increased dividends. They also found that young firms have a higher propensity to fund the repurchases at an increasing phase over the past and repurchases have become a preferred payout source for these firms. The study also shows although the tendency for larger firms is not to cut down the dividends, yet they show a higher propensity to use repurchases as a source of payout. The following graph shows the proportion of the firms that follow different payout methods over the period 1974-1988.

The general finding of the study is that firms have gradually substituted dividend payouts with stock repurchases. This finding is consistent with the finding of Fama & French, (2001) that even after controlling the firm characteristics firms have a lower propensity to pay dividends than in the past. However, according to Grullon & Michaely, (2002), in the period before 1983, regulatory measures have constrained the repurchasing decisions of the firms.

Baker, Mukherjee, & Powell, (2005) consider the different ways in which the investors receive the distribution from the corporations. Regular cash dividends, specially designated dividends (SDDs), and share repurchases have important implications for investors. The specially designated dividend payments have been one of the recent origins and are recurring for regular dividend increase firms (Lie, 2000).

The authors find that the main motive for adopting the repurchase route is to take the benefit of the perceived market’s undervaluation of shares. When the corporations are able to make strong earnings and higher cash flows they tend to increase the dividend payouts and the specially designated dividend payments. However, the investors have to treat the SDDs as a temporary phenomenon. The SDDs need to be interpreted, as indicating positive information about the current excess performance of the firm and it is not indicative of the long-term performance of the firm.

Ikenberry, Lakonishok, and Vermaelen, (1995) examined the long-run firm performance about the impact on open market share repurchase announcements made during the year 1980 to 1990. The study revealed that in respect of glamour shares where there is no undervaluation by the market is possible no positive drift in abnormal returns was observed. However, with respect to value stocks, the market erred in the initial response and the market does not react to the information conveyed through repurchase announcements.

Dividend Signalling

The essence of signaling is that the manager sets the dividend policy of the company for the benefit of himself and for the benefits of all the shareholders in general. However, it is not enough if the manager sets the dividend policy in order to maximize the intrinsic value of the firm. He must also consider the effect of dividend policy on the current stock price even if the current stock price does not reflect true value. Dong, Robinson, & Veld, (2005) have analyzed the reasons for the investors’ preference for dividends through a questionnaire to a Dutch investor panel.

The findings of the study indicate that investors prefer to receive dividends partly due to the reason that the transaction costs of cashing in dividends are lower than the transaction costs entailed in selling the shares. The answers confirm the signaling theory of Miller & Rock, (1985) and Bhattacharya, (1979). The study also proves that the behavioral theory of Shefrin & Statman, (1984) would apply to stock dividends and not for cash dividends. Dong et al (2005) also prove that individual investors do not tend to consume a larger part of their dividends and the investors would like to receive stock dividends in the place of cash dividends.

Summary

Through the review of different articles on the subject of dividend policy, this chapter provided the opportunity to gain further knowledge in the area of dividend policy. Stock repurchases have been dealt with in detail in the chapter along with a detailed review of the impact of the dividend policy on the stock price movements.

Empirical Results

On the empirical side, Jensen (1986) proves that an actual takeover is not required to enlarge the return of the resources to shareholders but through a thorough restructuring, the surplus funds available with the firm can be effectively distributed to the shareholders. He cites Arco restructuring provided gains to stockholders ranging from 20 to 35% of market value, which in monetary terms amount to $ 6.6 billion. The restructuring involved repurchase of from 25 to 35% of equity involving over $ 4 billion in cash outflows. With a view to reducing the cash resources available at the disposal of the managers, the company substantially increased the cash dividend, sale of assets, and major cutbacks in capital spending.

Since the article by Easterbrook (1984) deals with the theoretical aspects of dividend policy and its ability to control the agency costs there is not many empirical data used by him in the paper. However, he tries to explain the impact of the dividend policy on the agency costs by an illustration. Assuming that a firm has an initial capital of 100 out of which 50 represents debt and the balance 50 is equity.

The amount was invested in a venture and with the earnings; the firm has raised its holdings to 200. With this situation, the creditors of a firm enjoy a more than sufficient security at the cost of the residual claimants paying a rate of interest unwarranted by the healthy financial position of the firm. Therefore, the firm can decide to pay a dividend of 50 and issue new debts worth 50. In this situation, while the capital of the firm would continue to be 200 the debt-equity ratio would have been restored to the original position and the interest rate also becomes appropriate to the risk the creditors’ are carrying.

Table IX of the empirical details in the article from Michaely et al (1995) shows the abnormal trading volume around dividend initiation and omission announcements. Table IX is reproduced below to explain the clientele effect due to omission and initiation.

Table IX. Abnormal Trading Volume around Dividend Initiation and Omission Announcements

From the table, it can be observed that the relatively minor increase in the percentage of volume during the event window and the decline thereafter suggests that even if there are changes in the clientele they are not that dramatic.

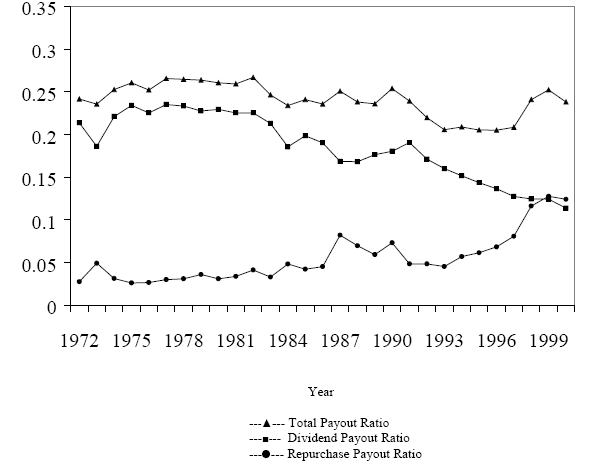

Jagannathan, Stepehens, & Wieisbach, (2000) constructed a database consisting of an underestimate and an overestimate of actual repurchases for every Compustat firm for the period between 1985 and 1996 and observe that the repurchases have actually grown over the period. In the year 1996, the actual repurchase volume was between $ 44.3 billion and $ 63.3 billion and this volume suggests that the repurchases have been considered as an economically important source of payout by the corporations. However, this volume is considerably less than the $ 141.7 billion paid out as dividends in the year 1996.

Grullon & Michaely, (2002) found that the number of firms that have initiated stock repurchase programs has increased from 26.6% in the year 1972 to 84.2% in the year 2000. The position is illustrated by the following graph.

The study by Dong et al (2005), out of the 555 responses received against a questionnaire sent to 2,723 smaller investors, shows 60.5% of the respondents indicate a higher preference for receiving dividends showing a preference score of 5 or above. This corresponds to a score of 4.98 on a scale of 1 to 7 where 1 indicates “I do not want dividends and 7 indicates, “I want dividends” with 4 as neutral). Only 12.3% of the respondents replied with an answer of 3 or below. This result shows a strong confirmation of the signaling role of dividends.

The study by Baker, et al., (2005) presents the following information as the main reasons for the corporations deciding to pay Specially Designated Dividends.

Reasons for Paying Specially Designated Dividends.

Frank & Jagannathan (1998) observed that in the Hong Kong, stock market for the period studied the dividend was HK $ 0.12 and the average price drop was HK $ 0.06. The authors have empirically proved their stand through market microstructure-based arguments.

The study by Ikenberry, Lakonishok, & Vermaelen, (1995) found the average abnormal four-year buy-and-hold return measured after the initial announcement is 12.1 percent. In respect of value stocks, companies are more likely to repurchase shares because of undervaluation, the average abnormal return is 45.3%.

Implications and Avenues for Future Research

The introductory part prepared the ground for the research on the subject of dividend policy by providing sufficient information on the concept of distribution of cash surpluses by corporations. The paper also deals with the implications of the distribution of cash surpluses by corporations in different ways. This research paper on dividend policy helps in distinguishing between the implications of cash dividend payouts and stock repurchases as one of the methods of distribution of cash surpluses by the corporations. The influence of agency cost issues in dividend policy considerations has been elucidated.

The articles reviewed provided for the enhancement in the knowledge relating to various concepts on the dividend policies being followed by the corporations and their impact on the market prices of shares. The stock repurchase area has been extensively reviewed through the study of scholarly articles. The concept of dividend signaling has been reviewed to find the reasons why dividend has been preferred by some class of investors. The empirical results in the form of regression analysis, tables, t-statistical values, and graphs provided greater insight into the area of dividend policy.

This review provides opportunities for further research in the area of dividend policy to the extent that there is a possibility that the necessity of the managers to consider the effect of adding a potential project on the total volatility of the firm’s asset portfolio and the resultant impact on the firm’s optimal dividend policy. The link between dividend policy and cash flow volatility with respect to different industry settings is another potential avenue for further research. The impact of dividend announcements on the stock returns in respect of stocks being dealt with in any of the emerging stock markets would be an interesting study to assess the investor behavior in the respective emerging stock market.

References

Allen, F., & Michaely, R. (2002). Payout Policy. Working Paper, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Asquith, P., & Mullins, D. W. (1983). The Impact of Initiating dividend payments on shareholders’ wealth. Journal of Business , 83, 77-96.

Baker, H. K., Mukherjee, T. K., & Powell, G. E. (2005). Distributing excess cash: the role of specially designated dividends. Financial services review , 14, 111-131.

Bernard, V. L., & Thomas, J. K. (1989). Post-earnings announcement drift: Dealyed price response or risk premium. Journal of Accounitng Research , 27, 1-36.

Bhattacharya, S. (1979). Imperfect information, dividend policy and the ‘bird in hand’ fallacy. Bell Journal of Economics , 10, 259-270.

Black, F., & Scholes, M. (1974). The effects of Dividend yield and dividend policy on common stock prices and returns. Journal of Financial Economics , 1, 1-22.

Brealey, R., & Myers, S. (1996). Principles of Corporate Finance Fifth Edition. New York: McGraw Hill.

DeBondt, W., & Thaler, R. (1985). Does the stock market overreact? Journal of Finance , 40, 793-808.

Dong, M., Robinson, C., & Veld, C. (2005). Why Individual Investors want dividends. Journal of Corporate Finance , 12 (1), 121-158.

Easterbrook, F. H. (1984). Two agency-cost Explanation of dividends. American Economic Review , 74 (4), 650-659.

Elton, E., & Gruber, M. (1970). Marginal stockholder tax rates and the clientele effect. Review of Economics and statistics , 52, 68-74.

Fama, E., & French, K. (2001). Disappearing Dividends: Changing from Characteristics or lower propensity to pay. Journal of Financial Economics , 60, 3-43.

Frank, M., & Jagannathan, R. (1998). Why do stock prices deop by less than the value of the dividend? Evidence from a country without taxes. Journal of Financial Economics , 47 (2), 161-188.

Grossman, S. J., & Hart, O. D. (1982). Takeover bids, the free-rider problem and the theory of Corporation. Bell Journal of Economics , 11, 42-54.

Grullon, G., & Michaely, R. (2002). Dividends, Share repurchases and the substituion hypothesis. Journal of Finance , 57 (4), 169-1684.

Healy, P., & Palepu, K. (1988). Earnings Information Conveyed by dividend initiations and omissions. Journal of Financial Economics , 21.

Ikenberry, D., Lakonishok, J., & Vermaelen, T. (1995). Marker underreaction to open market share repurchases. Journal of Financial Economics , 39 (2), 181-208.

Jagannathan, M., Stepehens, C. P., & Wieisbach, M. (2000). Financial Flexibility and the Choice between Dividends and Stock Repurchases. Journal of Financial Economics , 57.

Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency Costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers. American Economic Review , 76, 323-339.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics , 3, 303-360.

Lie, E. (2000). Excess funds and agency problems: an empirircal study of incremental cash disbursemens. Review of Financial studies , 13, 219-247.

Michaely, R., Thaler, R. H., & Womack, K. L. (1995). Price Reactions to Dividend Initiations and Omissions: Overreaction or Drift? Journal of Finance , 50 (2), 573-608.

Miller, M., & Modigliani, F. (1961). Dividend Policy, Growth and the Valuation of Shares. Journal of Business , 34, 411-433.

Miller, M., & Rock, K. (1985). Dividend Polciy under Asymmetric information. The Journal of Finance , 40, 1031-1051.

Murphy, K. J. (1985). Corporate Performance and Managerial Remuneration: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics , 7, 11-42.

Ross, S. A., Westerfield, R. W., & Jaffe, J. (2002). Corporate Finance Seventh Edition. New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hills Publising Co.

Shefrin, H. M., & Statman, M. (1984). Explaining Investor preferences for Cash dividends. Journal of Financial Economics , 13, 253-282.

Shiller, R. J. (1981). Do Stock Prices move too much to be justified by subsequent changes in dividends. American Economic Review , 71 (3), 421-436.