Introduction

In day-to-day life, a number of children and adults are exposed to a variety of domestic violence. Some of the violence overspills and affects the psychological development of the children, especially when the latter are at their early stages of development. In order to curtail the extensive damage of domestic violence, there should be legal orders to minimize and eventually stop their occurrence. The escalating criminal activities have necessitated the legal intervention that should be executed in a hands-on manner.

This could help prevent the couples from engaging in fierce actions than being in rush to counter the aftermath of already committed criminal activities. This research seeks to determine the impacts of domestic violence orders in reducing the escalating cases of family brutality in most households. The researcher conducted this study using qualitative and quantitative techniques, particularly applying interviews and surveys in carrying out the study. Therefore, this study was conducted using a practical design.

A Criminal Justice Intervention

Notably, domestic violence is a crime that a number of couples often commit among themselves or against the children in the homestead (Bacchus, 2004). Usually, the aggression could lead to physical harm, assault, sexual abuse, stalking, and intimidation among other forms of battering. Bacchus (2004) asserts that the extent of damage that such violence causes in the family could be as great as the death of either couple or the child who suffers the abuse.

Therefore, it needs a criminal justice intervention to prevent the occurrence of such abuse or stop it altogether. More importantly, the assertion of the Department of Health (2003) that the criminal intervention should be proactive, thus preventing the parents from engaging in violent actions than being reactive to the already committed offenses. Department of Health report (2005) revealed that a proactive approach in dealing with a domestic criminal act is vital as it might enhance family integration and overall development.

Notably, a child who grows up in a non-violent environment is more likely to be violent than those who grow under the care of hostile and ever quarreling parents (Department of Health, 2003). Therefore, this research would utilize the existing literature to ascertain the significance of domestic violence orders in reducing the occurrence of such aggressions.

An Evaluation Question

This study asks, do domestic violence orders reduce quarrels in the family? This question is critical in understanding the extent to which the domestic violence orders help in reducing acts of aggression among the couples or against the children in the family.

Hypothesis

In investigating and evaluating the question for this study, the null and alternative hypotheses are as follows;

- N0: There is no significant relationship between domestic violence orders and the occurrence of acts of aggression in the family.

- N1: There is a significant relationship between domestic violence orders and the occurrence of acts of aggression in the family.

Literature Review

In reducing the family aggressions and protecting the household members, the Council of Europe report (2002) postulates that domestic violence orders are the most important practices that many countries adopt. In most households, cases of aggression such as physical harm, assault, sexual abuse, stalking, and intimidation have increased and left many wondering for where to get assistance (Council of Europe, 2002).

Many people have not adhered to policies, which aim to prevent the household members from suffering gross violation of the people’s rights to peaceful environment without engaging much in aggression (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2005). In this regard, many women suffer in the hands of their brutal husbands similar to the ordeals that some men go through under the rules of their wives. As Council of Europe report (2002) pointed out, this situation has led to a lot of family breakages, with children developing hostility as they grow due to continuous expose to the actual violent acts of, or from their parents.

In Washington, for example, a judge may agree to sign a paper that is usually called “a domestic violence order for protection” (DVOP), to inform the abuser to end his/her aggression against the other partner or face dear harsh legal repercussions (WomensLaw, 2011). The United States uses this criminal justice intervention to give the victims, whether male of female legal and public protection from the aggressors. The government realised that this was critical in reducing the affects of criminal injustices to the people who might be suffering in homesteads.

In Washington, domestic orders for protection are of two types, namely the “ex parte temporary order for protection” and the “final order for protection” (WomensLaw, 2011). The “ex parte temporary order for protection” is usually the first to be signed in the court for preliminary protection of the victim until the case is heard and determined.

Here, the “ex parte” means the accused would be absent for the hearing. This temporary order can be affected after the victim has explained to the judge that he/she needs protection from domestic violence.

At this stage, the offender might not be required to present him/her for hearing. Notably, this first hearing is carried out immediately or the next court session after filing the petition. Once the judge ascertains that the victim is in danger, he/she would issue a temporary order of protection to the endangered person. Notably, temporary orders stay in force for a maximum of 14 days and must indicate the date it expires.

On the other hand, the “final order for protection” is granted after the court schedules and hears all the sides of the story (WomensLaw, 2011). In this case, the accused will justify his/her aggressions against the partner, while the victim would justify the call for protection by explaining the reasons for thinking that he/she is in danger. This means both parties will present evidences to justify the claims before the judge, who then analyse each before delivering the verdict.

This hearing must be within fourteen days after the issuance of the temporary order. Once the judge is satisfied that the victims actually needs protection, he/she will issue a protection order that may last for a given period or permanently, depending on the case at hand (Dodd, 2004). According to the Department of Health (2003), the protection order with a fixed timeframe might be renewed after its expiry if the person still fells unsafe in the hands of the aggressor.

In the United Kingdom, domestic violent protection orders are also taken seriously by the authority (Povey, 2004). For example, the Family Law Act of 1996, section 42 of part IV, contains a non-molestation order (Answers Corporation, 2012). This order protects ex-partners and current partners from aggressive actions including intimidation, hurting and harassing among others (Answers Corporation, 2012).

In the UK, the protection orders also extend to the children in the household and same-sex couples suffering from domestic violence and other forms of family abuse (Answers Corporation, 2012). The UK government considers this order as so important that ignoring it is a serious crime and attract severe punishment fro authority. Despite the level of the victim’s level income, the non-molestation order is issued as part of the legal aid (Answers Corporation, 2012).

Evaluation Design

Since the researcher conducted the exploration from a qualitative and quantitative perspective, the study took a practical design. For instance, the interview and online survey were the practical means of collecting data in this study (Saris & Gallhofer, 2007). Using this design, the researcher interviewed those who had suffered domestic violence and asked whether they tempted to obtain protection order from the authority.

Using this design, the sampled population who took part in the interview got enough time to interact with researcher in the process of obtaining the truth, relevance and significance of restraining orders, which the offenders suffered (Saris & Gallhofer, 2007). On the other hand, the surveys also had simple and structured questions about the victims experience with the restraining orders.

The design also helped the researcher to engage the respondents in answering the questions related to the effectiveness of restraining orders in controlling sequential aggressions (Saris & Gallhofer, 2007). The research also aimed at determining if the victims of domestic violence experienced increased risk for their lives through reporting the family aggressions to the authorities. In addition, the comparison of the interview and survey outcome employed in this research design also helped the researcher understand the change in behavior of the offenders (Saris & Gallhofer, 2007). The question applied to the period after they were served with a restraining order to stop their aggression against their partner or children.

Sampling Approach

In this investigation, the researcher used random sampling in selecting the participants for the study (Tabachnick, Fidell & Osterlind, 2001). In addition, the selection of participants was done through random sampling, which is representative and non-discriminative.

Sample

Under this methodology, the sample of participants was drawn from members of households, including men, women and children who had undergone domestic violence. Since there were many prospective participants from the community, out of 50 prospective participants, the researcher selected 10 people as the sample size. The different categories under which the participants were divided was based on the gender, in which the males constituted 45 percent, females constituted 35 percent and the children were 20 percent.

Data Collection Methods

The researcher applied interviews and surveys in collecting the data (Tabachnick, Fidell & Osterlind, 2001). The researcher ued interview and survey methodologies in collecting the data. In this case, interview was a highly interactive, multivariate method and the interviewer could seek more explanation from the interviewees (Tabachnick, Fidell & Osterlind, 2001).

In carrying out the research, the researcher already had set questions for the interview, thus the process was semi-structured. However, the questions did not have a particular structure, but varied to suit the different categories of participants, including the males, females and children. The interviewees were asked three questions related to the organisational culture and stress (Tabachnick, Fidell & Osterlind, 2001). Since the questions were open-ended, the participants were expected to give their opinion on each problem.

Alternatively, the survey was a simple and efficient methodology that the researcher used in collecting the data (Tabachnick, Fidell & Osterlind, 2001). In this case, all the employees from the four departments were allowed to participate. In this case, the researcher used non-convenience sampling because it does not use possibility that could hinder someone from participating in the study.

Findings

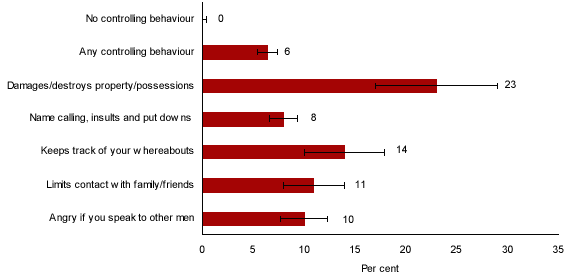

Available statistical findings put percentages of people experiencing domestic violence as below.

Explanation

Considering the figure, domestic violence led to a very high number of damages of the households, standing at 23 percent (Australian Institute of Criminology, 2009). The number of couples who were keeping track of their partner’s whereabouts was posted at 14 percent, while those who curtailed contacts with close friends of family members were at 11 percent (Australian Institute of Criminology, 2009). Husbands who get hungry when their wives speak to other men were at 10 percent, while eight percent engaged in insults and name calling among others abuses, and six percent showed controlling behaviour (Australian Institute of Criminology, 2009).

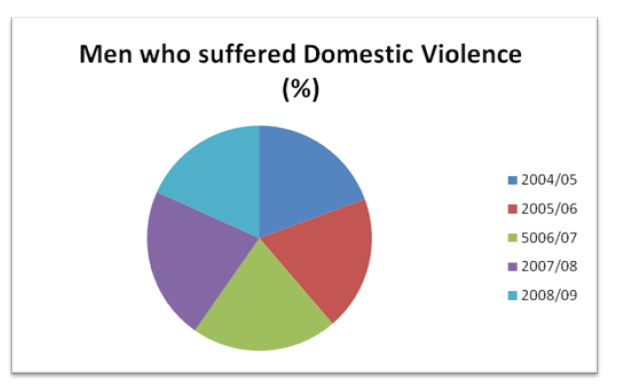

Approximate Average domestic Violent Men Experience in UK by year

Table 2: Men who experience domestic violence

The graphical presentation of the figure is

Explanation

According to the British Crime Survey, the institution indicated that the number of reported cases of domestic related assault stood at an average of forty percent (Campbell, 2010). The research showed that the number of male victims was posted at 43.4 percent in 2006/07, 45.5 percent in 2007/08 and 37.7 percent in the year 2008/09 (Campbell, 2010). This figure was against the norm that it is mainly women who undergo domestic violence. The report also indicated that the people take male casualties as “second-class victims”, and sometimes overlooked (Campbell, D. (2010).

The study also established that a number of people whose behavior was questionable and the ones that carried out aggression on members of the family changed the acts after noting that the partners had obtained restraint orders from the court. This showed their fear for encountering the full force of the law. However, although the rate of repeated aggressions against the family numbers reduced, the number of new cases that were reported in various households.

This finding made the researcher accept the alternative that states, “There is a significant relationship between domestic violence orders and the occurrence of acts of aggressions in the family”. Alternatively, the researcher rejected the null hypothesis, which stated that “there is no significant relationship between domestic violence orders and the occurrence of acts of aggressions in the family.

Conclusion

In summary, the research evidenced that domestic violence is real and affecting many families. The research also evidenced that the domestic violence orders prevented the re-occurrence of aggression as the couples witnessed low levels of cruelty between each other. Alternatively, some acts of aggression over-spilled and affected the psychological development of the immediate family members such as the partner and children, especially when the latter were at their early levels of development.

References

Answers Corporation, (2012). Restraining Orders. Web.

Australian Institute of Criminology, (2009). Family/Domestic Violence Statistics. Web.

Bacchus, L. (2004). “Domestic violence and health.” Midwives vol.7, no.4.

Campbell, D. (2010). More that 40% of Domestic Violence Victims are Male, Report Reveals. Web.

Council of Europe, (2002). Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the protection of women against violence. Strasbourg: France Council of Europe.

Department of Health, (2003). Mainstreaming Gender and Women’s Mental Health: Implementation Guidance. London: Department of Health.

Department of Health, (2005). Responding to domestic abuse. London: Department of Health.

Dodd, T., et al., (2004). Crime in England and Wales 2003-2004. London: Home Office.

Garcia-Moreno, C. et al. (2005). WHO Multi-Country Study on Domestic Violence and Violence against Women. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

Povey, D. (2004). Crime in England and Wales 2002/3: London: Home Office.

Saris, W. & Gallhofer, N. (2007). Design, Evaluation, and Analysis of Questionnaires for Survey Research. New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell.

Tabachnick, B., Fidell, L. & Osterlind, S. (2001). Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon Boston.

WomensLaw, (2011). Domestic Violence Orders for Protection. Web.