Research Objectives

The objective of this research is to determine the most important factors that affect citizens’ attitudes toward using e Government services in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, the research aims to determine the most important factors that affect citizens’ continuous intention to use e Government services in the country. It is felt that these research objectives will lead to significant findings that not only underscore the citizens’ usage of e government services, but also specifically provide a broader perspective of the usage process. Moreover, findings of this study will help to fill the gap in the literature by providing a better and comprehensive understanding of the usage process of e government services.

Research Questions

The present study is guided by the following research questions:

- What are the most important factors that affect citizens’ attitudes toward their first use of e Government services in Saudi Arabia?

- What are the most important factors that affect citizens’ continuous intention to use e Government services in Saudi Arabia?

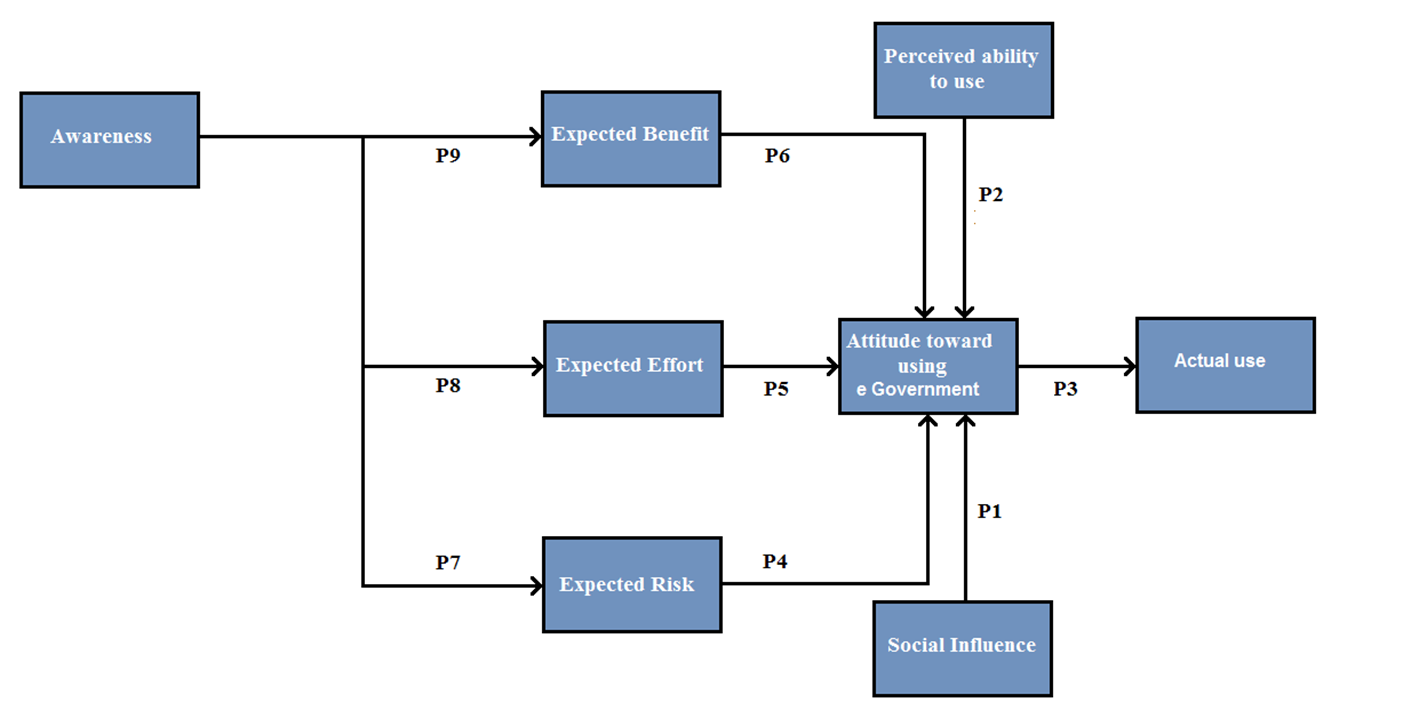

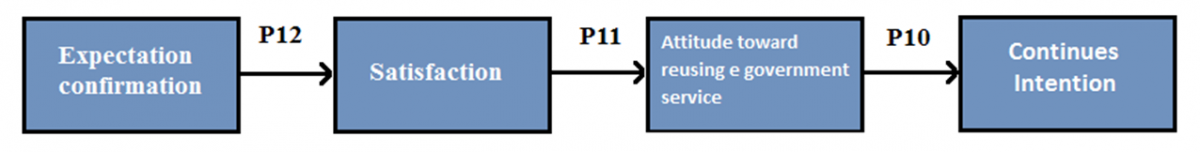

Proposed model for research

Propositions

Research Methodology

Introduction

This section discusses and develops the research methodology of the underlying study, including the research philosophy, research approach, research strategy, population and sampling, methods of data collection, as well as the justifications used by the researcher in selecting the methodology for the research study. In addition, the section discusses the unit of analysis, level of analysis, reliability and validity, and data analysis techniques.

Research Philosophy

A number of philosophical paradigms have been applied in IS studies, with available literature demonstrating that these paradigms have different views and different assumptions about the nature of the world or reality (ontology), what we can be able to establish using current knowledge (epistemology), and how we can go about acquiring the needed knowledge (methodology) (Oates 2006). In their exploration, Wynn and Williams (2012, p. 788) acknowledge that “ontology refers to assumptions about the nature of reality, epistemology refers to the evidentiary assessment and justification of knowledge claims, and methodology is concerned with the process or procedures by which we create these knowledge claims.”

Undoubtedly, the mounting interest in the core research positions of ontology, epistemology and methodology has been brought about by their extensive applicability in the domain of information systems (IS) research, which in turn has obliged IS researchers to develop an in-depth understanding of their guiding principles (Venkatesh, Brown, & Bala 2013; Zachariadis, Scott & Barett 2013). In this section, we discuss the ontological, epistemological and methodological positions as applied in IS studies with the view to selecting the appropriate method for use in answering the key research questions and ensuring the present study meets the set research objectives.

Ontology

Although there are three different perspectives that represent the different ways to understand the world and reality at the oncology level, the frequently used ones are objectivism and subjectivism. In presenting an argument about these two streams of oncology, Pooper (1934) acknowledged that objectivity is associated with the independence of a person’s feelings or thought system, whereas subjectivity relates to feelings of conviction. Theorists and researchers have continued to view the two ontological perspectives as increasingly incompatible and unable to guarantee a peaceful coexistence of multiple methodologies (Venkatesh et al 2013), hence the introduction of a third ontological perspective referred to as critical realism. MacKinnon (1985) is of the opinion that critical realism combines the insights of objectivity and subjectivity.

Epistemology

At the epistemology level, there are also three different views about what we can know about any knowledge, though the two dominant streams are represented by positivism and interpretivism. The third stream, known as the critical view, has been added by some authors for use in IS research (Oates 2006; Venkatesh et al 2013).

Positivism provides the groundwork for traditional scientific methods that are based on objectivity and precision in what is commonly referred to as quantitative research. Owing to the fact that the major goal of positivism is to achieve accurate, valid and absolute truth, the methods used to find this truth must always be grounded on objectivity (Riordan 2005). Consequently, in quantitative research studies utilizing the positivism philosophy, the researcher not only relies on empirical data as the primary source of information but also employs positivist assertions for developing knowledge, such as the cause and effect paradigm, reduction to precise variables or phenomena of interest, hypothesis testing, utilization of measurement and observation, as well as the assessment of theories (Bryman & Bell 2008).

On the other hand, interpretivism denotes a naturalistic or humanistic philosophy which focuses on the effects human values, beliefs, practices, and life experiences have on individuals. Unlike positivism which relies on objective, numeric facts to gain knowledge, the main focus of interpretivism is to study the subjective “human” side of issues using qualitative approaches (Riordan 2005). Interpretivism in mainstream IS research is a philosophical paradigm that is primarily concerned with understanding the subjective meanings that research subjects assign or attach to a given phenomenon of interest within a specific context or area of concern (Wynn & Williams 2012). For instance, the researcher can use interpretivism perspective to deduce the study participants’ subjective meanings of what the events sequence in e government usage actually entails.

Finally, the critical view is considered for use in IS research if the study entails a dimension of social critique. Klein and Myers (1999) stated that the critical view philosophical paradigm assumes that social reality is historically constituted and produced and reproduced by individuals, and hence is often used in scenarios that demonstrate restrictive and alienating conditions to the status quo. In IS research, the critical view or the critical realism epistemology “seeks to posit descriptions of reality based on an analysis of the experiences observed and interpreted by the participants, along with other types of data” (Wynn & Williams 2012, p. 793). Consequently, according to these authors, the resulting knowledge claims are primarily centered on attempting to identify and explain those elements of reality that must exist in order for the phenomena under investigation (events and experiences) to occur.

Weber (2004, p. iv) discussed the differences between positivist and interpretive research approaches, as shown in Table 1 below

Table 1: Main Differences between Positivist & Interpretive Research Paradigms

Research Approaches

There exist different approaches that can be used by researchers to undertake a research study and selection of any approach is purely informed by the aim of the study as well as the type of data to be collected. Available literature demonstrates that the main research approaches include quantitative research, qualitative research, and mixed methods approach (Venkatesh et al 2013), and that each of these research approaches has its own advantages, disadvantages and general purpose, as discussed below (Creswell 2014).

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research entails a systematic investigation that makes use of computational techniques in order to provide answers to questions that may pertain to the relationship between and among constructs or variables (Creswell 2003). As such, quantitative research has fixed rules in terms of collecting and analyzing data, not mentioning that it relies heavily on mathematics and statistics as fundamentally important tools in the process of analyzing quantitative data. Additionally, in quantitative research, analysis of data usually occurs only after all the data have been collected from the field (Berg & Latin 2008).

Qualitative Research

The qualitative research approach involves a critical investigation of processes that aim to answer the “why” questions of a certain phenomenon of interest (Creswell 2003). This approach relies on non-quantifiable data derived through qualitative research methodologies as opposed to quantitative research which relies on quantitative information or statistical analysis. Moreover, the approach is primarily concerned with providing insights into human behavior, implying that it relies on subjective rather than objective data (Creswell 2003).

In most occasions, qualitative methodologies are quite flexible as they only rely on semi-structured instruments to collect data. In a qualitative research, the participants tend to dictate the extent and direction of the researcher’s data gathering strategies. However, qualitative research is often limited by the fact that general conclusions made as a result of employing its methodologies are only applicable to the specific cases included and hence they cannot be generalized to the wider population (Berg & Latin 2008).

Mixed-Methods Approach

The mixed-methods research approach integrates qualitative and quantitative research methodologies into one framework in an attempt to provide a scientific approach to providing answers to a research problem while at the same time qualifying and validating the findings through a less structured means of data collection (Rogelberg 2002). As postulated by Creswell (2003), the mixed-methods approach combines philosophical assumptions and methods of inquiry. As such, a research that utilizes mixed-methods approach involves philosophical assumptions that guide the direction the researcher takes in data collection and analysis, not mentioning that a mixture of qualitative and quantitative approaches are used in many phases of the research process as the two approaches works best in complimentary rather than competing roles (Creswell 2003).

Research Designs

Case Study

In a case study, the researcher engages in a comprehensive qualitative exploration of a single person, program, event, process, institution or organization with the view to learning more about a little known or vaguely understood situation or phenomenon of interest (Williams 2007). A case study must be operationalized within a defined time-frame and the researcher is at liberty to employ a combination of techniques (e.g., direct/participant observations, interviews, archival records or documents, physical artifacts, and audiovisual materials) for the purpose of data collection.

Survey

Creswell (2003), cited in Welford et al (2012, p. 34), notes that “a survey provides numerical description of trends, attitudes or opinions of a population by studying a sample of the research population.” In survey research, the design, population, sample, as well as the choice of instrumentation are predetermined by the researcher before going into the field to collect data using questionnaire schedules or structured interviews.

Ethnography

Deeply rooted in anthropological studies, ethnography studies an entire group of the population that shares a common interest, implying that the researcher must become immersed in the daily lives of the study participants with the view to observing their behavior before making any interpretations (Williams 2007). Data for ethnographic studies are mainly gathered through participant observations and interviews, implying that it is a qualitative research design.

Experiment

Extant literature demonstrates that experimental research is quantitative in approach and entails a process whereby “the researcher investigates the treatment of an intervention into the study group and then measures the outcomes of the treatment” (Williams 2007, p. 66). As posited by this author, the experimental research design must have an independent variable that does not fluctuate and a control group that is not randomly selected for purposes of establishing points of divergences/associations between independent variable/control group and dependent variables/experimental groups.

Justifications for Research Methodologies Used

Drawing from the above elaboration, the present study uses a positivism paradigm, a quantitative research approach, and a survey (cross-sectional) research design to not only determine the most important factors that affect citizens’ attitudes toward using e Government services in Saudi Arabia, but also to identify the critical factors that affect citizens’ continuous intention to use e Government services in the country. Additionally, the study employs standardized questionnaire instruments to collect primary field data in line with a positivist paradigm and a quantitative research approach. This section discusses the justifications that have informed the researcher to select the mentioned paradigm, research approach, research design or strategy, as well as method of data collection.

A Rationale for using the Positivism Paradigm

There are a number of reasons why positivism is considered the most suitable paradigm for use in not only investigating the most important factors that affect citizens’ attitudes toward their first use of e Government services in Saudi Arabia, but also in establishing the most important factors that affect their continuous intention to use e Government services.

First, owing to the fact that positivism assumes that the main purpose of research is scientific explanation and views social science as an organized method for combining deductive logic with accurate empirical observations of individual behavior (Creswell 2003, pp. 6-7), it therefore follows that this paradigm is effective in guiding the researcher to use the tenets of objectivity and stability of reality to discover and confirm a set of probabilistic causal laws that can then be applied to predict the factors that affect citizens’ attitudes toward their first use of e Government services in Saudi Arabia (Gelo, Braakmann, & Benetka 2008, p. 274; Lee & Hubona 2009, p. 238; Creswell 2014, pp. 6-7).

Second, owing to the fact that the comprehensive review of the literature has demonstrated that various variables may be at play in influencing citizens’ attitudes toward e Government services, a positivism paradigm is better placed to assist the researcher in manipulating the reality by varying the variables with the view to identifying regularities in, and forming relationships between, some of the constituent variables used to successfully address the study’s objectives and research questions (Creswell 2014, pp. 6-7). Furthermore, a positivist research philosophy allows the researcher to rely on quantitative measures for collecting and analyzing data intended to make predictions and generalizations on what factors come into play to influence citizens’ continuous intention to use e Government services in Saudi Arabia (Yilmaz 2013, p. 323).

In spite of these justifications, a positivist research philosophy does not have any regard for the subjective states of individuals because it views human behavior as passive, controlled and determined by external environment (Gelo et al 2008, pp. 274-275). This predisposition goes against the conviction that IS research should strive to demonstrate the interaction between individuals and technology (Pinsonneault & Kraemer 1993, p. 80).

A Rationale for using the Quantitative Approach

Creswell (1994), comprehensively cited in Yilmaz (2013, p. 311), defines the quantitative research approach “as a type of empirical research into a social phenomenon or human problem, testing a theory consisting of variables which are measured with numbers and analyzed with statistics in order to determine if the theory explains or predicts phenomena of interest.” Drawing from this description, a quantitative research approach is justifiable for use in the present study as it assists the researcher to expand available theoretical frameworks and also to use numerical figures to develop a process model that can be used to identify the key factors affecting citizens’ attitudes toward continuous intention to use e Government services in Saudi Arabia.

Additionally, a quantitative research approach allows the researcher to reduce e Government usage dimensions to numerical values that are then used to carry out statistical analysis aimed at determining the relationships between these dimensions in terms of generalizable causal effects (Gelo et al 2008, p. 268). As demonstrated by these researchers, this capacity enables the researcher to make viable predictions on the phenomena of interest based on rigid rules of logic and measurement. Consequently, a quantitative research approach is better placed than a qualitative research approach to assist the researcher in responding to the underlying research questions by investigating the relationships between the variables that come into play to affect citizens’ attitudes toward their first use of e Government services as well as their continuous intention to use the services.

Lastly, owing to the fact that the present study aims to determine the most important factors that affect citizens’ attitudes toward using e Government services in Saudi Arabia, it is imperative to employ a quantitative approach as it is useful in studying a large number of people using a representative sample and then generalizing the findings to the whole population (Sekaran 2006, p. 115). Moreover, data collection using some quantitative methods such as questionnaires is relatively quick and quantitative data analysis is relatively less time consuming due to use of available statistical software packages (Bryman & Bell 2008, p. 55).

A Rationale for using Survey Research

This study uses a cross-sectional (survey) research design, as study participants are contacted at a fixed point in time to gather important data on the most important factors that affect the attitudes of citizens toward using and continuous intention to use e Government services in Saudi Arabia (Newman 2003, p. 112; Fowler 2008, p. 187). Consequently, the first justification of using survey research is embedded in its capacity to enable the researcher to use a standardized survey questionnaire to generate quantitative descriptions of some aspects of the studied population through evaluating the relationships between variables (Pinsonneault & Kraemer 1993, pp. 80-81), which in turn serve as the basis for developing a comprehensive process model of citizens’ usage of e Government services in the country.

Additionally, available literature shows that survey research avails “a quantitative or numeric description of trends, attitudes, or opinions of a population by studying a sample of that population” (Creswell 2014, p. 13). Consequently, the second justification relates to the fact that survey research enables the researchers to come up with numeric descriptions of attitudes and opinions on e Government use that could be easily generalized to the whole population based on the fact that the data generated from the sample are based on real-world observations (Sekaran 2006, p. 116; Fowler 2008, p. 188). Other justifications for using survey research include ease of application, cost effectiveness, and capability to collect a broad range of data; however, this research design has received criticism for selection bias, lack of clarity in demonstrating temporal bias, and incapability to show causality (Bryman & Bell 2008, p. 58; Marsden & Wright 2010, p. 121).

A Rationale for using the Questionnaire as the Data Collection Instrument

Available literature demonstrates that questionnaires are basically “fixed sets of questions that can be administered by paper and pencil, as a Web form, or by an interviewer who follows a strict script” (Harrell & Bradley 2009, p. 6). One of the justifications for using structured questionnaires as the primary means to collect field data relates to the fact that the researcher has the capacity to contact a large number of participants at a comparatively low cost, which in turn ensures that study findings can be generalized to a wider population (Fowler 2008, p. 188). Second, through the use of Web-based protocols to administer the self-reported questionnaires to participants, it is easy for the researcher to reach more people who are spread across a wide geographical location and hence save on time and cost considerations (Newman 2003, p. 115; Polonsky & Waller 2010, p. 202).

Additionally, the use of structured questionnaires to collect data in this particular study is justified as it has been easier to leave the schedules with the participants to complete them at their own convenience or at a time when they feel that they have all the required information (Sekaran 2006, p. 181). Such a capability, according to this researcher, provides participants with an avenue to respond comprehensively to the questionnaire items and seek for clarifications where necessary. Other justifications for using questionnaires to collect primary data in this study include:

- demonstrated capacity to minimize bias which is often caused by the characteristics of the interviewer and variability in interviewer skills,

- demonstrated capacity to avail greater anonymity to study participants due to absence of the interviewer in the actual completion of the instruments,

- low training requirements for the person administering them based on the fact the schedules are self-administered (Polonsky & Waller 2010, p. 205; Barnham 2012, pp. 736-737).

Unit and Level of Analyses

This research focuses on the usage process of e Government services in Saudi Arabia. Consequently, citizens as users or non-users of e Government services form the unit of analysis because they comprise the major entity that is being analyzed in the study. Owing to the fact the study targets individual users or non-users of e Government services to assist in determining the most important factors that affect people’s propensity to use e Government services in Saudi Arabia, it therefore follows that the level of research analysis is grounded on the individualized use or non-use of e Government services.

Population & Sampling

In the present study, the target population comprises users of e-government services in Saudi Arabia. Available literature demonstrates that Saudi Arabia’s first national e Government strategy, referred to as the YESSER Program, was launched in 2005 with the view to creating user-centric electronic initiatives that focus on enhancing government services to the public sector (Alateyah, Crowder, & Wills 2011, p. 601). Today, the country provides innovative e Government services to its citizens through various government ministries and agencies. For example, the Saudi government provides the eDashboard portal which verifies the identity of citizens and serves as a single sign-on portal where individuals can access all services provided, the Open Data Initiative which serves citizens with documents and reports from ministries and government agencies, and e-participation forums which collect public opinion through surveys, public consultations and blogs (United Nations 2012, p. 27).

Drawing from this elaboration, it is obvious that many government ministries and agencies in Saudi Arabia provide e Government services to citizens. However, for the purpose of data collection, the researcher has employed a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria with the view to selecting a governmental department capable of providing rich contextual data in line with the objectives and research questions of the study. The criteria used to select the government department include:

- Department must be active in the provision of a certain type of digital or internet-based service to Saudi citizens;

- Department must be of substantial size and demonstrate a direct impact on the general public owing to the nature and scope of e services provided;

- Department must demonstrate a particular benefit to users/recipients of its services (e.g., issuing passports, re-entry visas etc), and;

- Department must be easily accessible to the researcher for purposes of data collection.

Based on these standards, the researcher selected the General Directorate of Passports in Saudi Arabia to serve as the basis for data collection. Afterwards, Convenience sampling technique was used to select a sample of 500 participants who use the e services offered by the directorate for the purpose of data collection via online or web-based protocols. Consequently, the sampling for this study has been done online through the assistance of personnel from the General Directorate of Passports. It is important to mention that the main considerations for inclusion of participants into the study sample are as follows:

- Must be an active user or beneficiary of the directorate services;

- Must be 18 years or older to ensure proper understanding of questionnaire items;

- Must be citizens of Saudi Arabia as the study is country-specific, and;

- May be of both gender and willing to participate in the study.

The main justification behind the selection of convenience sampling is that the researcher has the leeway to choose the most readily available subjects to participate in the study (Hair et al 2007, p. 105). Additionally, convenience sampling is not only easier to administer, but it costs less than other sampling techniques in terms of resources, not mentioning that it assists the researcher in the collection of pertinent information that would not have been possible using probability sampling techniques (Vogt 2007, p. 277).

Reliability and Validity

In quantitative research, reliability estimates the consistency of the measurement used by the researcher in data collection or the degree to which a test or procedure generates similar results under the same condition and with the same participants, while validity is largely concerned with evaluating the degree to which a measure accurately represents the concepts it claims to measure (Boudreau, Gefen, & Straub 2001, pp. 11-12; Straub, Boudreau, & Gefen 2004, p. 382). This section demonstrates how the researcher ensures the reliability and validity of the measurement instrument as well as the study findings.

Reliability

In this particular study, the reliability of the measurement instrument and study findings are achieved through:

- standardizing the questionnaire instrument,

- adequately preparing the participants for the study,

- reinforcing the objectivity of the researcher and reducing bias during the data collection phase,

- ensuring the questionnaire is properly worded and easily understood by study participants,

- ensuring that data in the questionnaires are rightly coded and interpreted,

- documenting changes or progress regularly,

- ensuring the stability of the different measures used in the data collection instrument,

- varying questionnaire items in wording and positioning to elicit fresh participant responses (Mouton & Morais 1996, p. 57 ; Straub et al 2004, pp. 382-383; Bryman 2008, p. 177; Bryman & Bell 2008, p. 194).

Validity

As demonstrated by Venkatesh, Brown, and Bala (2013, p. 32), “validation is an important cornerstone of research in social sciences, and is a symbol of research quality and rigor.” Unlike in qualitative studies where validity is established through member checking, triangulation, thick description, peer reviews and external audits, validity in quantitative research is only established through measurements, scores, instruments used, as well as the research design (Mouton & Morais 1996, pp. 61-62). There are three expansive categories of validity in quantitative research studies, namely “(1) measurement validity (i.e., content and construct validity), (2) design validity (i.e., internal and external validity), and (3) inferential validity (i.e., statistical conclusion validity)” (Venkatesh et al 2013, p. 32).

According to Venkatesh et al (2013, p. 32-33), “measurement validity estimates how well an instrument measures what it purports to measure in terms of its match with the entire definition of the construct.” In the present study, the researcher ensures content validity (extent to which an evaluation represents all components of activities within the domain being evaluated) by ensuring that the enrolled sample is representative of the whole Saudi population in terms of e Government usage and intention to use (Mouton & Morais 1996, p. 65). Construct validity, according to Venkatesh et al (2013, p. 33), refers to “the degree to which inferences can legitimately be made from the operationalizations in a study to the theoretical constructs on which those operationalizations are based.” Consequently, the researcher ensures construct validity in the research study by (1) validating the questionnaire instrument and the theory underlying it, (2) undertaking a comprehensive review of related literature to have adequate understanding of all the focal constructs, (3) ensuring that the number of items included in the questionnaire instrument are adequate and are piloted to ensure consistency, and (4) describing the necessary attributes/characteristics of the used constructs as narrowly as possible (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Podsakoff 2011, pp. 294-295; Westen & Rosenthal 2003, pp. 609-611).

Design validity incorporates internal and external validity, whereby the former denotes the level of approximate truth about inferences regarding cause-effect relationships in a scientific inquiry, while the latter denotes the level to which the findings of a research study can be generalized to other research settings and groups (Venkatesh et al 2013, pp. 32-33). Drawing from this description, the researcher achieves internal and external validity in the present study by (1) ensuring the relevance, appropriateness, and representativeness of items in the self-completed questionnaire through piloting with persons who are similar to the intended study participants, (2) comparing the standardized questionnaire instrument to other similar validated measures of e Government usage and adoption in developing countries, (3) ensuring the representativeness of the sample drawn to conduct the study, and (4) establishing the correct operational measures for the theoretical concepts and variables under examination through successfully linking the questionnaire items and measures (e.g., Lickert-type scales) to the study’s main objectives and research questions (Bryman & Bell 2008, p. 211; Punch 2009, p. 185).

Lastly, inferential or statistical conclusion validity is associated with the findings of quantitative studies, and refers to the proper application of statistics to infer whether the presumed independent and dependent variables covary (Venkatesh et al 2013, p. 32-33). Zachariadis, Scott, and Barett (2013, p. 859) describe inferential validity as “the validity of the statistical conclusions and whether they are sufficient in order to make inferences.” In this study, the researcher ensures inferential validity by (1) guaranteeing the conclusions of the study follow from the preceding data analyses, (2) making certain that no other alternative conclusions could have been arrived on the basis of the available evidence, and (3) guaranteeing that mathematical associations between constructs are assured within particular degrees of confidence (Mouton & Morais 1996, p. 287; Straub et al 2004, pp. 382-383).

Data Analysis

After cleaning and coding the questionnaires from the field, data have been entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 18.0) software program for descriptive and inferential analysis. The software has also been used to develop descriptive tables, cross tabulations, bar graphs, and pie charts for presentation and interpretation of the study findings.

In the present study, descriptive statistics have been used to provide simple summaries on the demographic characteristics of the participants and the various measures used by the researcher to determine the most important factors that affect citizens’ attitudes toward using e Government services in Saudi Arabia. As such, univariate data analysis has been conducted not only to develop frequency distributions and subsequent interpretations of the various attributes and issues of interest to the study, but also to demonstrate measures of central tendency (e.g., mean, median and mode) as well as measures of dispersion (e.g., standard deviation and variance) in describing results. It is important to mention that descriptive statistics are used in this study because of their capacity to collect, organize, and compare enormous quantities of discreet categorical and continuous non-discreet data in a more manageable way, and also due to their capability to identify with ease discreet or finite categorical variables, including participant’s sex, age, e Government usage patterns, and intentions for use (Connolly 2007, p. 381; Trieman 2008, p. 202).

Inferential statistics are utilized in the present study not only to demonstrate the relationship between variables of interest, but also to test the strength of the relationships with the view to determining if such relationships occur by design or chance (Treiman 2008, p. 205). More specifically, inferential statistics (ANOVA and correlation analysis) have been used in the present study to (1) make inferences from the analyzed data to more general conditions concerning the most important factors that affect the citizens’ attitudes toward using e Government services in Saudi Arabia, (2) make predictions on how these factors affect e Government usage and continuous intention to use patterns, (3) investigate the differences between various participant responses, (4) demonstrate important insights into the relationships between variables, and (5) generate convincing support for the development of a comprehensive process model for e Government services usage in Saudi Arabia (Asadoorian & Kantarelis 2005, p. 57; Connolly 2007, p. 385; Runyon 2010, p. 220).

Reference List

Alateyah, SA, Crowder, RM & Williams, GB 2011, ‘Factors affecting the citizen’s intention to adopt e-government in Saudi Arabia’, World Academy of Science, Engineering, & Technology, vol. 82 no. 2, pp. 6-1-606.

Asadoorian, MO & Kantarelis, D 2005, Essentials of inferential statistics, University Press of America, Lanham, MD.

Barnham, C 2012, ‘Separating methodologies’, International Journal of Market Research, vol. 54 no. 6, pp. 736-738.

Berg, K & Latin, R 2008, Essentials of research methods in health, physical education, exercise science and recreation, 3rd edn, Lippincott & Williams, Baltimore, MD.

Boudreau, MC, Gefen, D & Straub, DW 2001, ‘Validation in information systems research: A state-of-the-art assessment’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 25 no. 1, pp. 1-16.

Bryman, A 2008, Social research methods, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Bryman, A & Bell, E 2008, Business research methods, 3rd edn, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Connolly, P 2007, Quantitative data analysis in education: A critical introduction using SPSS, Routledge, New York, NY.

Creswell, JW 2003, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 2nd edn, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Creswell, JW 2014, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches, 6th edn, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Fowler, FJ 2008, Survey research methods, 4th edn, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Gelo, O, Braakmann, D & Benetka, G 2008, ‘Quantitative and qualitative research: Beyond the debate’, Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science, vol. 42 no. 3, pp. 266-290.

Hair, JF, Money, AH, Samuel, P & Page, M 2007, Research methods for business, Willey, London.

Harrell, MC & Bradley, MA 2009, Data collection methods: Semi-structured interviews and focus groups, RAND Corporation, Web.

Klein, HK & Meyers, MD 1999, ‘A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 23 no. 1, pp. 67-93.

Lee, AS & Hubona, GS 2009, ‘A scientific basis for rigor in information systems research’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 33 no. 2, pp. 237-262.

MacKenzie, SB, Podsakoff, PM & Podsakoff, NP 2011, ‘Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing relationships’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 35 no. 2, pp. 293-334.

Marsden, PV & Wright, JD 2010, Handbook of survey research, Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, BD.

Newman, WL 2003, Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches, Allyn and Bacon, Boston.

MacKinnon, B 1985, New Yorker, American Philosophy: A historical anthology, Google Book.

Mouton, J & Morais, HC 1996, Basic concepts in the methodology of the social sciences, 5th edn, HSRC Publishers, Pretoria.

Pinsonneault, A & Kraemer, KL 1993, ‘Survey research methodology in managing information systems: An assessment’, Journal of Management Information Systems, vol. 10 no. 2, pp. 75-105.

Oates, BJ 2006, Researching information systems and computing, Sage Publications Ltd, London.

Polonsky, MJ & Waller, DS 2010, Designing and managing a research project: A business student’s guide, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Pooper, K 1934, New Yorker: The logic of discovery, Google Book.

Rogelberg, SG 2002, Handbook of research methods in industrial and organizational psychology, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Runyon, RP 2010, Descriptive and inferential statistics: A contemporary Approach, 5th edn, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Sekaran, U 2006, Research methods for business: A skill building approach, 4th edn, Wiley-India, New Delhi.

Straub, D, Boudreau, MC & Gefen, D 2004, ‘Validation guidelines for IS positivist research’, Communications of the Association for Information Systems, vol. 13 no. 1, pp. 380-427.

Trieman, DJ 2008, Quantitative data analysis: Doing social research to test ideas, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

United Nations 2012, E-government survey 2012: E-government for the people, Web.

Venkatesh, V, Brown, SA, & Bala, H 2013, ‘Bridging the qualitative-quantitative divide: Guidelines for conducting mixed methods research in information systems’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 37 no. 1, pp. 21-54.

Vogt, WP 2007, Quantitative research methods for professionals, Allyn and Bacon, Boston.

Weber, R 2004, ‘The rhetoric of positivism versus interpretivism: A personal view’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 28 no. 1, pp. 3-12.

Welford, C, Murphy, K & Casey, D 2012, ‘Demystifying nursing research terminology: Part 2’, Nursing Researcher, vol. 19 no. 2, pp. 29-35.

Westen, D & Rosenthal, R 2003, ‘Quantifying construct validity: Two sample measures’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 84 no. 3, pp. 608-618.

Williams, C 2007, ‘Research methods’, Journal of Business & Economic Research, vol. 5 no. 3, pp. 65-72.

Wynn, D & Williams, CK 2012, ‘Principles for conducting critical realist case study research in information systems’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 36 no. 3, pp. 787-810.

Yilmaz, K 2013, ‘Comparison of quantitative and qualitative research traditions: Epistemological, theoretical, and methodological differences’, European Journal of Education, vol. 8 no. 2, pp. 311-325.

Zachariadis, M, Scott, S & Barett, M 2013, ‘Methodological implications of critical realism for mixed-methods research’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 37 no. 3, pp. 855-879.