Abstract

This research is a crucial one that investigates and evaluates the formulation of the e-sale contract under the laws of Islam. The project aim is to study the legal changes in this contract under the studies and guidance of four Islamic Sunni Schools which have been selected for this research.

The current research report is a comprehensive study that involves a thorough study of the objectives and rules about the formation of the e-sale contract. These are examined in light of the general principles of contract laid out by the Islamic law (Shariah) which form the basis of contractual dealings between individuals and businesses. For a sale contract to be established, it is imperative that a minimum of two parties are present out of which one puts forth an offer which the second party then accepts. The sale contract becomes binding once acceptance of terms formulating the deal is achieved.

The current research examines similar arrangements of the sale contract in the electronic environment where parties enter into a contract to exchange products or services via the web. The legal contract binding sales or e-sale contracts over the internet are usually in the form of email, EDI, etc.

Thus, through this research, a comprehensive understanding is developed by studying and presenting a whole range of vital literature which would help in presenting the main elements of e-sale contracts under the general rule of Islamic law. Such dealings through the internet and eventual e-sales may involve different legal consequences which may be difficult to comprehend by those lacking sufficient understanding. This research would help in increasing the awareness by providing a much study of issues related to the basic phases of the formulation process involving contracts and respective obligatory requirements under Islamic law.

The current report is structured chapter wise where each chapter provides important information regarding the topic and important conclusions are presented in the final chapter supported by a crucial literature review and findings from the current research.

Introduction

Islamic law today is the product of almost fourteen centuries of continuous development commencing early in the seventh century AD. The understanding of the general term ‘law’ used in English is only a small part of a much wider concept in the Islamic teachings – Shariah. The term Shariah is relatively comprehensive and has a much wider scope which is not possible to be rendered the use of a single word in English. The term Shariah may be complemented and closely approximated to the term ‘religion’ where Shariah could be considered as the prescriptive side of religion.

Shariah not only covers various aspects of human life in this world but also guides life hereafter. It, therefore, deals with providing reasoning for particular human behavior and expectations of human beings from following a particular way of life. It consists of teachings from the Islamic Holy Book and Hadith regarding preferred culture, principles of religion and ethics, code of law, and other disciplines of life which are considered an integral part of human life helping humans to develop their beliefs, intelligence and perform different acts of life which help them in building relationships with God and other human beings.

In the last two decades, the internet and e-technology have contributed tremendously by shaping up how communications are taking place and have turned the face of the world around where distances have become meaningless and tons of information is easily and freely available on the net. The trend of the use of information technology has not been limited to certain countries but it has been spread without boundaries. In the Islamic world, the technology had been till recently used mainly to spread Islamic education and propagation, defending negativities against the religion and other religious purposes. In addition to these, there has been limited application of technology for commercial and entertainment purposes.

The Qur’an is considered to be the most revered of books in Islam and is frequently regarded as the Holy Book. It serves to guide Muslims in all walks of life and all ages. Analogical expressions allow the book to be more than productive and far more than adequately adaptable for all modern innovations.

Since modern-day knowledge has become increasingly integrated with innovations in Information Technology, it comes as no surprise that the Quran advises its followers to pursue knowledge regardless of the hurdles that come forth. The very first verses of the Quran called the follower to read in the name of his Lord and Cherisher and to acknowledge his Lord’s uniqueness by acknowledging the fact that He is the supreme creator and He created all mankind from nothing more than a congealed clot of blood.

As information technology represents a shift to new areas of knowledge, by implication, it is an area that is important for Muslims to learn about, and explore its potential for good purposes.

The Qur’an encourages its followers to engage actively in work that is productive to them. In this regard, the Quran gives frequent references to elements such as business and other commercial activities as well as direct references to trade on numerous occasions. According to the Quran, engaging in productive activities should be perceived as a duty and no doubt remains when the Holy Prophets Mohammad’s (PBUH) saying is considered in which he has clearly stated that a person seeking knowledge is a person who God will lead to heaven and to do so, He shall make sure that there are angels by the individual’s side to guide him.

In another instance, the Prophet referred to the return of seeking knowledge as a reward that would be far more than what the individual initially had in mind when he began his pursuit of knowledge but if the individual did not manage to make it through, the person would still be rewarded.

We can infer from these verses and numerous other verses that the Quran and the Sunnah of the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) that there is an extensively high degree of importance given to the pursuit of knowledge in Islam and this leads us to concur that no part of Shariah denounces the pursuit of knowledge in any way. It is essential to note that this understanding does not exclude the use of technological innovation as a means to facilitate the process of the pursuit of knowledge since Shariah has not distinguished between any specific means or technologies that can be used. Hence, by doing so, Shariah gives room to the use of all forms of technology, including those that are generally brought into use in the case of e-commerce transactions. Hence, if this particular perspective was considered to be empirical, Shariah approves the use of technology that is generally brought into use during e-commerce transactions.

However, the development of information technology has led us to one of the most significant revolutions in our lives in the form of a close-knit society based on the internet. This has had a direct implication on the methods through which businesses are conducted in everyday life and elements such as competition commerce and businesses, in general, are perceived. In fact, the global presence of the Internet serves to stimulate buying and selling through the E-Commerce platform. E-Commerce here is being regarded as the actual process through which electronic buying and selling are carried out through multilateral use of networking, digital technology, and the internet.

However, it is essential to highlight at this point that even though e-commerce has taken on the form of a global phenomenon, it is still one that many Muslims do not make use of in light of a deficiency of information on the subject of the Islamic perspective on transactions made through e-commerce.

Since little has been done to regulate this phenomenon according to the Islamic legal system, the main aim of the thesis is to establish that the general principles for ordinary sale contracts in Islamic law are appropriate to govern the formation of electronic sale contracts. The second aim is to provide a resource for all readers, researchers, interested individuals, and organizations doing business by e-commerce contracts under Islamic law, whether they approach it from a business, information technology, or legal background.

Issues of the legality of the formation of e-sale contracts in Islamic law shall be considered and shed light upon in an attempt to reflect on the benefits that e-commerce holds for Muslims across the globe and to elaborate on the legality of the use of e-commerce in the frame of reference of Islamic principles. Regarding transactions via e-sale contract, the issues of offer and acceptance through the internet will be studied to clear Muslim doubts as to the Islamic law’s approach to the valid formation of the e-sale contract. Countless seminars and conferences have been held alongside even more books on the subject. With the challenge to fulfill this gap, the thesis shall take on a perspective through which it shall elaborate on the e-sale contract in light of Islamic perspectives and the potential hurdles that can come forth in the development of the same.

It is beyond the scope of this thesis to examine all kinds of contracts recognized in Islamic law. The center of attention in the case of this thesis shall be the sale contract. The part of the thesis constituting the legal framework shall relate to the laws of sale contract as the contract par excellence in Islamic law. A model shall be used in the form of the fundamental principles of the e-sale contract in Islamic law. It shall be considered that this contract is one upon which other contracts rely as per Islamic law. Moreover, the sale contract is dealt with much more extensively in fiqh (the science of the Shari’ah) writing than other contracts, which are presumed to be regulated by analogy to it where appropriate.

The thesis will examine and analyze the relevant literature and legislation. It will argue that the following legal issues may arise when forming sale contracts in an electronic environment under the general principles of ordinary sale contracts in Islamic law:

- Has a valid offer and acceptance been formed in the e-sale contract?

- With whom has the e-sale contract been formed (legal capacity)?

- When and where was the e-sale contract formed?

- Are there legal uncertainties when determining the precise point in time that an e-sale contract has been formed?

- If an offer to enter into an e-sale contract specifically requires acceptance to be communicated in a certain form, whether an electronic communication of acceptance will be effective to form an enforceable contract?

- How can we identify the object and consideration in the e-sale contract?

Each of these issues will be discussed in the thesis relying on the general principles governing the formation and validity of the ordinary sale contract in Islamic law.

As such, the thesis presents an aspect of the ongoing research by Muslim scholars from around the world aiming to analyze the status of e-commerce from an Islamic perspective. However, our thesis will be limited to and rely on Fiqh cases from the jurists in the four major Sunni Islamic schools (the Hanafi, the Maliki, the Shafi’i, and the Hanbali). These schools have greater common features between themselves, which frequently makes it easier and more correct to write our thesis, by way of generalization, on these schools.

The thesis will start in chapter 1 by familiarising readers with the background of Islamic law principles. The thesis shall initiate by putting forth an elaboration on Islamic law and shall proceed from this foundation onwards. This foundation is meant to serve as an outline and a highlighting of the specific relevance of this research and therefore it should not be considered to be anything along the lines of an extensive delving into Islamic Law. We will describe the main contract principles under Islamic law, to clarify the scope of this thesis. We will note the important basic features of Islamic law regarding contracts, highlighting the way they facilitate the sale contract.

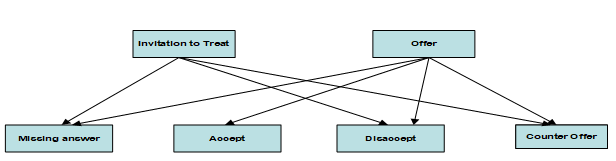

In chapter 2, the thesis discusses the validity of the e-sale contract from the Islamic point of view. At this stage, the initiation of the e-sale contract between both parties begins through a check of the binding pillars of the contract. Offer and acceptance are the most commonly found constituting pillars in this regard along with the two contracting parties and the exact expression mode. The most important point that we will discuss at that initial stage is that these pillars in the e-sale contract must meet the Islamic requirements. Moreover, in this chapter, we will analyze the different kinds of Contracts that can be classified as Islamic Commercial Contracts. It is imperative to note that these incorporate those that relate to ordered sale (bay’ al-Salam), manufacturing sale (bay’ al-Istisna) as well as Deferred Sale (bay’ Muajjal).

Chapter 3 will cover basic notions relating to the formation of e-sale contracts under Islamic law and is divided into four sections. The first section deals with basic features of psychological elements. The second section will treat the exteriorization of psychological elements, making reference to subjective and objective, or consensuality and formalistic approaches in Islamic law. The third section will review various means of expression, being the word of mouth, writing, sign and conduct, and silence. The fourth section will examine the efficacy of these means of expression in the internet environment under Islamic law.

Chapters 4 and 5 will be the common analysis of an agreement in terms of offer and acceptance or, conversely, the treatment of offer and acceptance as the commonest mechanism for reaching an agreement. This entails a separate examination of various aspects of the mechanics of offer and acceptance in the formation of the e-sale contract, including their correspondence, and the nexus between the mechanism and the related agreement under the principle of Islamic law. Our discussion in these chapters first deals with an offer, and second with acceptance (including its correspondence with the offer) and the import, or contents, of an e-sale contract comprising its terms and conditions and interpretation.

Finally, chapter 6 will be the conclusion of the thesis and its implications.

An Introduction to the Study of the E-sale Contract Under Islamic Law

Islamic law (Shari’ah) is considered by Muslims to be the expression of the will of God, representing his final law governing men’s behavior in this life and the hereafter. It is also regarded by some as an eternally valid and immutable standard of law. This is revealed in classical Islamic legal theory, which declares that no man has the right to interfere with Shari’ah or to change its rules. “It is comprehensive, universal, eternal, and not susceptible to change; its contents are set out in the authoritative codices of the orthodox schools.”

Changes, therefore, can only be effected by the word of God through his revelation, to which men have had no access since the death of the Prophet Mohammed. Moreover, since God alone is the lawgiver, and the right of law-creation is possessed by him alone, it follows that man does not have the right to create law. Man’s involvement is thus confined solely to the application of Shari’ah.

However, some modern Muslim scholars have defined Shari’ah in an alternate way. They believe that this approach is no longer sufficient, and have thus resorted to a number of different methods to overcome this predicament. For example, Maududi distinguishes between the part of the Shari’ah which has a “permanent and unalterable character and is, as such, extremely beneficial for mankind, and that part which is flexible and has thus the potentialities of meeting the ever-increasing requirements of every time and age.”

Another well-known example is the opinion of Fazlur Rahman, who, although he defines the Shari’ah to include “all behavior – spiritual, mental and physical”, also recognizes that the legislative provisions of the Qur’an have to take into account the attitudes and beliefs of the then existing society. This view, therefore, entails the acceptance by scholars that people do have the right to enact change to legislation, as long as it falls into the broad parameters of Islamic understanding.

Scholars of this new understanding of Shari’ah believe that law-creation, which is the right of God alone, should not be confused with the comprehension and discovery of God’s law. Therefore, they do not doubt that Shari’ah should develop and evolve continuously with the advancement of human beings’ thought and civilization. They believe that it is a gross mistake to assume that Shari’ah of the seventh century is still suitable, in all its details, for application in the twenty-first century. The perfection of Shari’ah lies in the fact that it is a living body, growing and developing along with the continuous progression of human beings, guiding their steps and directing their way towards God, stage by stage. Human life will continue on its way back to God inevitably.

Thus, in order to help the Shari’ah accommodate the ever-changing and ever-developing human beings, Muslim jurists devised Usul al-Fiqh. By doing so, the difference between the changeable and the constant and the reason for the classification of the same is brought forth along with any new debate that has to be subject to the Quran test which will be explained later in the chapter. In the event that a clear and undoubtedly approval from the Quran is acquired, the change is integrated into Muslim society. Otherwise, it is tested for the Sunnah of the Prophet Mohammed (P.b.u.h). If there is not a clear sign of approval in the Sunnah, then the approval will then lie on the shoulders of other Islamic sources.

This chapter will therefore be divided into five parts, the first dealing with the classical structure of Islamic law, the second with the progressive concept of Shari’ah and Fiqh, including a study of Islamic jurisprudence, its methods of interpretation, the authority of the jurisprudential rules and the development of such jurisprudence. The third part of this chapter will examine the modernization and possible future of Shari’ah. The future of Islamic law is discussed here, in light of its present authority and the ‘heated’ debates that occur in the contemporary Muslim world. The fourth part addresses the Islamic perspective of e-commerce, taking into account its legality, Islamic business ethics, and e-commerce sale contracts. The fifth part deals with the general principles that apply to sale contracts.

The Classical Structure of Islamic law

The structure of Islamic law is rooted in the Qur’an and the teachings of Prophet Mohammed and the interpretations of these sources of revelation by his followers. Islamic law serves as a provider of the right Shariah and governs the relations between mankind and Allah. It would therefore be reasonable to consider it to be nothing less than divine law established by Allah and communicated through the Quran.

Therefore, the sources are put at four: the Qur’an and the Sunnah, which are primary, and the Consensus (Ijma) (sources in common between Sunni and Shi’ah schools) and reasoning by analogy (Qiyas) for Sunni or ‘Reason’ for the Shi’ah, which are secondary. There are other sources of lesser importance that will govern the sale contract in the absence of any rule in the primary and secondary sources such as custom (urf), necessity (darura), and judicial contribution.

Since Islamic law is our main subject, a look at some of its general characteristics would show how it compares in this regard with other legal systems such as Common law and Roman law. The first point which deserves to be emphasized in my thesis is that Islamic law comprises two main divisions based on the relations between men and between humans and Allah. The first, the acts of worship (Ibadat), deals with purely religious matters (these include recitation of the ‘shahadah’, Prayers ‘salah’, Fasts ‘sawm’, Charities ‘zakat’, Pilgrimage to Mecca ‘hajj’), and the second, the transactions (al-Mudumalai), deals with all those subjects which comprise the only content of other legal systems, which include judicial matters, warfare, peace, drinks, punishments, penal, inheritance, marriage, divorce, and financial transactions.

Primary Sources

The Qur’an and the Sunnah are considered to be primary sources in Islamic law. Also, in light of the consideration of the fact that their rules are penned down, they are also generally regarded as verses (Nusus) which may be translated as Script or Text, forming the written authority.

The Qur’an

The Qur’an is considered to constitute the essence of Islamic Law and is therefore regarded as the most significant Holy Scripts of the Muslims. It is composed of 114 chapters; each chapter presents different verses and sheds light on numerous subjects. It is however imperative to note that the Quran does not address specific legal prescriptions. Approximately 80 of the 6000 verses constitute the Quran pertaining to law. The arrangement of the Qur’an in its present chapters and verses was made under the Third Caliph, Uthman.

The Qur’an contains, among such matters as historical narrations, fables, ritual observances, and what pertained to the Prophet’s life, specific principles that can be generalized along with numerous elaborative discussions on legal matters. These are scattered through various chapters and are far from being comprehensive. Some earlier verses were abrogated by later ones, while some others are in apparent contradiction with each other.

All verses, however, have been retained and form part of the whole body. Broadly speaking, earlier verses handed down in Mecca, thus known as the Mecci verses, are more general in import, tolerant in spirit, and of an ethical nature. Those revealed later in Madinah, thus known as the Madani verses, are more detailed, and make up the majority of the legalistic rules, imposing specific commandments and abrogating certain (Mecci) precepts.

In the early period of Islam, the Qur’an as the Word of God was not open to comment. As time went by, as an outcome of the opposing views of different dogmatic segments across Islamic history, many commentaries, both Sunni and Shi’ah, have been produced which greatly help its understanding; but no matter how scholarly some may be, none is considered a binding authority.

The Sunnah (Tradition)

While the Prophet (P.b.u.h) was living, he would answer the queries of his followers, adjudicate their disputes, and pronounce rulings which were considered, next to the commandments of the Qur’an, rules of law. The Sunnah is the performance and methods of the Prophet Mohammed. In the start, following his death, litigation would be dealt with through reference to Qur’anic verses; in the event that none was found to provide a solution, the Sunnah was brought into use.

The Sunnah constituted the tradition, speeches, and actions of the Prophet Mohammed (PBUH). The Sunnah, therefore, appendages, illuminates and elaborates the provisions of the Qur’an. However, it is significant to realize that even though the modus operandi of verification of authenticity and recording of Sunnah was undertaken by a large number of Muslim scholars of the second century of Islam, only the compilations of six scholars have come to be accepted by the majority of Muslims as containing the sound of genuine Sunnah.

Thus, since then, the Sunnah has become a definite source of Islamic law. However, the Sunnah is still considered a supplementing source and cannot be considered to supersede the Quran. In the event of such a contradiction, it is implied that the alleged Sunnah is weak or false.

however, based on the definition of Sunnah, it is indispensable to highlight the reasons why the Sunnah is multipurpose and therefore adaptable in a form such that it can handle present-day problems and issues coming forth as a result of the increasing intricacy of life. In a modern-day community, moral tension exists in the form of a range of legal as well as administrative intricate problems. The theological and moral dimensions of expanding Islamic society have given way to numerous controversies. Even though new material was considered and incorporated, the ideal Sunnah was kept intact as a consideration source.

This particular process of interpretation began with the comrades of the Prophet explicitly as well as tactically resulting in the deducing of numerous norms with practical applications in modern-day society while keeping the rules of the Quran in performance.

Secondary Sources

The reason behind Shari’ah as a system that is religious and legal brings it to a point where there is no doubt left that it is to be inferred from no source other than the Qur’an; second from the Sunnah. In case the primary sources (the Qur’an and Sunnah) are silent on the issue, then the consensus (Ijma) and reasoning by analogy (Qiyas) will follow as a source of Shari’ah according to the four Sunni schools.

Consensus (Ijma)

In the event that the Sunnah does not provide the required level of clarity in guidance with regard to the subject issue, the third source for Islamic Law is present in the form of Ijma. It is a combined agreement across Islamic scholars of a particular age group regarding the rule of law that is most appropriate to the issue. It is imperative to note that the Ijma is an inference derived from independent legal reasoning on areas where the Ijma has to be resorted to. It is only permitted in areas where the Quran and the Sunnah provide no definitive instructions. The jurists represent the Muslim community in this regard and seek to reach agreements on issues. Once an agreement is reached, the resolution to the issue becomes integrated into Islamic jurisprudence.

The Ijma comes into action only in cases where there is a no directly or indirectly applicable testament in the Qur’an and the Sunnah but it is important to note that it should not under any condition contradict them.

Ijma was found in its most profound form in the beginnings of Islamic law during times when the community used to be of a form such that it would be fairly small and very few eminent jurists existed. This allowed the views of all the jurists to be acquired.

Reasoning by Analogy (Qiyas)

In the event that the Ijma also does not serve as an adequate Muslim judge, the Qiyas is referred to. It is only resorted to in the case when no legal authority on an issue exists and in this case, the ruling of the Qiyas is generally based on an accepted principle and is considered to be “from the explicitly known to the explicitly unknown” would fit such a particular rule in relation to an issue at hand.

Principles of reason, effectively used for practical purposes as logical devices for the inference of detailed rules out of primary sources and the Qiyas, which are placed last in the formal hierarchy of conventional sources, have in fact made a contribution, at least in all Islamic schools, no less impressive than the other sources. Muslim jurists’ views and opinions expressed and employed in numerous expositions and commentaries under each school or trend have also contributed to contracts in Islamic law.

Other Informal Sources

The other sources of Islamic law consist of

- custom, which has through the ages influenced the development of the detailed rules of Islamic law;

- compendia, commentaries, and religious rulings which, according to all Islamic schools, have shaped, supplemented or influenced the respective law; and

- reconsidered thoughts and writings from Muslim scholars in the late nineteenth century onwards, which put a fresh interpretation on the age-old rules of Islamic law to bring them into line with modern needs, and subsequent legislative formulation in certain areas of Islamic law in the respective Muslim countries.

Progressive Concept of Shari’ah and Fiqh

A part of Shari’ah more concerned with the actual behavior of man in this world is termed Fiqh which consists of detailed rules and is closer than Shari’ah to the concept of law, though often the two original terms are used as synonyms. Fiqh, in spite of having a narrower ambit than Shari’ah, covers a much broader area than law by including such rules as those on purely religious observance. A substantial part of Fiqh, however, correlates to the present-day notion of law.

For convenience, Shari’ah or Fiqh is often rendered in English by the term ‘law’ and sometimes by the term ‘jurisprudence’, though the latter is apt to generate confusion because of its particular use in English for a branch of jural study on the theoretical basis and philosophical aspects of the law.

Faqih (sing: Fuqaha) is a scholar who is versed in Fiqh and, being religious, is required to be pious and observant. He is a religious jurist, sometimes referred to in Western literature as a ‘jurisconsult’. In the following research, we shall generally employ ‘law’ for Fiqh, which itself is a part of Shari’ah and not infrequently equated with it, and shall utilize ‘ religious jurist’, or simply ‘jurist’, for a Fuqaha.

Another clarification to be made concerns the concepts of ‘school’. Islamic law is not a uniform or unitary system. It consists of subsystems according to various schools. A ‘school’ refers to a particular Islamic faith and the related subsystem of law, each a system in itself, and not to a trend of jurisprudential doctrine or thought.

There are five major Islamic schools today of which four are Sunni and the fifth is the Shi’ah, itself divided into several branches of which the most important is the Twelve (Ithna Ashari). Depending on the level of comparison, these schools present differences that distinguish them from each other and similarities that bring them together. There are notable differences in methodology and detailed rules between these schools. Our reference to the particularity of Sunni law in this research is exclusive to the four Sunni schools, Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’I, and Hanbali.

It may, therefore, be said, as a first categorization, that there are Sunni schools and Shi’ah schools, albeit that each is divided into individual branches. In a broader context, all the schools, whether Sunni or Shi’ah, have a common core in history, sources, classification, methodology, and so on, which makes it possible (notwithstanding variations and disunity in details) to treat Islamic law as a comprehensive system on its own, distilled from the general features of its various schools and branches.

All the four Sunni schools developed from the beginning of the second/eighth century. They were founded by, and respectively named after, pious and learned men, each referred to as ‘Imam’. These schools are the Hanafi, founded by Imam Nu’man Abu Hanifah (d.150/767); the Maliki, founded by Imam Malik ibn Anas (d. 180/796); the Shafi’i, founded by Imam Mohammed ibn Adris al-Shafi’i (d. 204/820); and, the Hanbali, founded by Imam Ahmad bin Mohammed bin Hanbal (d. 240/855). Each, particularly the Hanafi school, was subsequently further developed by the respective disciples of the founding Imams who were themselves eminent jurists in their own right.

The Traditionalist and the Rationalist schools of thought are two schools that have come forth as a result of the evolution of Islamic law through these two approaches. These are associated with their respective differing views on the law sources. However, considering Quran as the empirical source, the former trend tends to restrict itself to Traditions (Sunnah), the words and deeds narrated from the Prophet Mohammed (P.b.u.h) as a source of the law, while Rational Principles (Aqli) are supplemented with the latter trend. The paragraphs to follow shall shed more light on the subject of the sources of these elements.

Of the four Sunni schools, the first two (Hanafi and Maliki) developed almost concurrently, and the third came about just after the first two and partly overlapped in time with the fourth. The Hanafi school, adopting a Rationalist approach, allowed the greatest latitude for ‘free reasoning’ (ra’y), while the Maliki school was Traditionalist. The Shafi’i school was eclectic, trying to reconcile the first two, for which reason its founder was accused of being a Traditionalist by the Rationalists and of being a Rationalist by the Traditionalists.

He was in fact both, but predominantly a Rationalist. He placed greater stress on Traditions than did the Hanafi but organized, for the first time, a set of Rational Principles (Usul al-Aqli’ah) for the inference of detailed rules out of primary sources which brought order to, and restrictions on, the application of reason. These principles were in due course further refined and developed into a separate Islamic methodological discipline called the Science of Principles, or Roots, of the law (Ilm Usul al-Fiqh).

The Hanbali School instituted a vigorous reversion to Traditionalism which was much later revived with a puritan austerity by the Wahhabi movement in the twelfth/eighteenth century, originated in Arabia by Mohammed ibn Abd al-Wahhab. Since the establishment of Saudi Arabia in 1926, the Hanbali faith has been revived and has been made the official school of Saudi Arabia.

The respective context of the development of these schools, together with their pairing off according to the said two tendencies, is significant. The Maliki and Hanbali, both Traditionalists in approach though different in degree, developed in Madinah, the city of the Prophet Mohammed (P.b.u.h) which is located in Saudi Arabia, after his death gradually lost its economic and political importance. Both schools, and their conservative approach, are therefore referred to as Madani, ‘of Madinah’. The Hanafi and Shafi’i developed in Iraq (the latter also partly in Egypt) which became at the time the economic and political center of the Muslim world.

When the formation of these four schools was completed in the second half of the third/ninth century, a conviction gradually grew and was formulated in a maxim which held that the ‘gate of Ijtihad (independent juristic reasoning for inference of detailed rules out of primary sources) is closed’ and the subsequent generations had to follow the respective teachings of the early masters of the four schools. This caused a millennium of virtual stagnation of Sunni law till the latter part of the nineteenth century. Generations of jurists, of course, kept working within each school, but mainly elaborating on the works of the respective masters and with a little original contribution.

Western writers such Gibb and Schacht have attributed this supposed abandonment of Ijtihad to the mood of uncertainty in the Muslim community brought about by the Tartar invasions and the sacking of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258. This, they say, made the Muslim scholars more inclined towards conservatism and less willing to accept innovation in religious thought. This view locked the Shari’ah into a fixed and inflexible mold and prevented it from adapting to modern times, contributing to its decline.

The idea persists today, in some quarters, that there must be no variation from the interpretations of Shari’ah laid down before the 11th century, and that this is the only “correct” version of Shari’ah. There is still considerable resistance to new ideas. The leaders of some conservative Islamic movements appear to want to return their societies to an imagined past “Golden age” of Islam where life was lived according to the example of the Prophet’s time. Interestingly, proponents of this view are usually very happy to reimpose medieval restrictions on women and ban cinemas and satellite dishes, but they see no contradiction in riding around in jeeps rather than riding camels or using rocket launchers and grenades to fight their wars, rather than the swords and bows and arrows the prophet’s companions used.

During the period of Western expansion between the 16th and 20th centuries, most Muslim countries came at some time under the commercial and political domination of one of the major European colonizing powers. The British ruled India and Malaya and at various times exercised political mandates in the Middle East; the Dutch controlled Indonesia, and the French ruled North Africa, and also exercised a sphere of influence over countries in the Middle East after the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

In these countries, the Shari’ah was replaced with European-style legal systems, except for areas of law such as family law and inheritance which were of little significance to the colonial powers. Even in countries that were not directly colonized by European powers, such as the Ottoman Empire, there was a tendency to “modernize” by adopting Western Legal systems. By the middle of the 20th century most Muslim countries had a “mixed” legal system, with Turkey – where Kemal Ataturk had completely abandoned the Shari’ah – at one extreme, and at the other extreme, only Saudi Arabia which retained an almost complete and traditional Shari’ah legal system.

The idea of “closure of the gate of Ijtihad” was never accepted by the Shi’ah schools, nor was it accepted by many influential Sunni Muslim thinkers, such as Ibn Taymiyah in the 14th century, Fazlur Rahman (d.1988), Mohammed Iqbal in Pakistan (d.1938), Hasan al-Bana (d.1949) and Mohammed Abduh in Egypt (d.1905), who maintained that despite the decline in the fortunes of Islamic civilization, which continued under Western colonialism, Ijtihad was still possible and still continued to be exercised. They argue that the four Sunni schools never claimed infallibility or finality for their interpretations of the Shari’ah and that it is a necessity and a duty for qualified Muslims to exercise Ijtihad in the present time. They hoped to develop a “new fiqh” that would modernize the laws within established parameters for the purposes of the emerging nation-state. Contemporary Muslim writers such as Abdullahi an-Na’im also accept this view.

Patrick Bannerman says that there are four main trends in modern Islamic thought. These are the:

- Orthodox conservatives who adhere strictly to the doctrine of taqlid;

- Quasi-orthodox conservatives, who hold views similar to the above but are forced to deal pragmatically with Western influences in their countries;

- Modernising reformers, who seek to interpret the fundamentals of Islam in the light of existing and constantly changing circumstances; and

- Conservative reformers, who hold that taqlid is wrong but set limits to the exercise of ijtihad.

Modernization and the Future of Shari’ah

As various Muslim countries attempted to modernize and “Westernise” their legal systems, it was clear that some of the traditional interpretations caused hardship and injustice – for example, the Hanafi rule prevalent in the Ottoman Empire and India that a woman could not obtain a divorce without her husband’s consent – and a solution in Shari’ah had to be found to alleviate this kind of problem. Islamic modernists proposed three complementary methods of alleviating hardship through Takhayyur and Talfiq, re-interpreting the Shari’ah text and the doctrine of Siyasa Shari’ah.

Takhayyur means making a choice from the variety of legal opinions offered by the eminent jurists of the past. It means that if a satisfactory solution to a problem can not be found within the opinions of the Islamic school predominant in a certain area, a solution may be adopted from the opinion of another Islamic school. Similar to this is the doctrine of Talfiq, which means combining part of the juristic opinion of one school with part of the opinion of another school or jurist in such a way as to establish a new legal rule.

Muslim scholars further demand the right to be free from the doctrine of taqlid and to be allowed to exercise ijtihad to formulate new legal rules from a new interpretation of the Qur’an and Sunnah. This means going back to the sources and considering whether interpretations other than the traditional ones are possible. For example, the Quranic verses on polygamy have traditionally been interpreted to give a Muslim man the right to have up to four wives at the same time. Some modernists contend that the Qur’an in fact effectively prohibits polygamy through the requirement to be just and fair to each wife, and if this is not possible, then to marry only one. The verse on polygamy is followed by a later verse which says:

“You will never be able to be fair and just between women even if it is your ardent desire”

Since fairness and justice are impossible, a man must therefore restrict himself to one wife.

Not surprisingly, the differences in opinions have led to differing interpretations of the law. Let us take, as an example, the lawfulness or otherwise of music and art in Islam. In some Islamic countries, there is a firmly held view among many Muslims that music is forbidden (haram). The proponents of this view rely on certain texts and ahadith which forbid “vain talk” and which mention only certain pursuits such as archery and horse breaking as being suitable for a believer.

Likewise, drawing, painting, and sculpture are held to violate the Quranic ban on making images and so open the path to idolatry. The Taliban in Afghanistan and some extremist Muftis in Saudi Arabia, on coming to power in these countries, but their extreme version of this opinion into practice, banning not only music but television, destroying audio and videotapes and new technology, and forbidding photography which was deemed to be forbidden as the making of images contrary to God’s law.

Opponents of this view distinguish the text and reject the ahadith relied on by these people as doubtful, and hold that according to the Qur’an, what is not expressly forbidden is permissible. They rely on certain other ahadith in which the Prophet approved of the musical entertainment of the Ansar. Thus they allow singing accompanied by musical instruments so long as the lyrics are not un-Islamic and neither the performer nor the audience is tempted into sin by the music.

Certain modern music with sexually suggestive or obscene lyrics would be outlawed under both views. Some hold that in art, the only sculpture is forbidden. Some impose conditions on what is allowable in art as in music. Consequently, the emphasis of traditional Islamic art has been on calligraphy and geometric design, although human and animal figures have sometimes been used in a secular setting.

In recent times, substantial political, economic and technological change has made urgent the need to find solutions in Islamic law to new problems and to re-assess some old rulings in the light of new knowledge.

Moreover, there are specialized areas where a religious scholar alone would not have sufficient technical knowledge to be in a position to give a proper opinion. In these cases, there is a necessity for collective ijtihad, which may be obtained through the formation of councils of religious and secular scholars who are specialists in their chosen fields. Such councils have already been formed in many Muslim countries, and even in Europe, where a “European Council for Fatwa and Research” was formed with its headquarters in London in March 1997.

As an example of this new ijtihad, until recently the only choice of infertile couples was to reconcile themselves to childlessness or to adopt or foster someone else’s child. Nowadays, artificial insemination, donation of eggs and sperm are all new medical possibilities to overcome infertility. Which of these, if any, are acceptable in Islamic law? There is no possibility of relying on the opinions of the classical scholars as they had certainly never heard of any such things, nor is there any mention in Qur’an or Sunnah. So the religious scholars needed to find new solutions through their own ijtihad.

Many of them agreed that the correct Islamic opinion was this: marriage is an essential foundation of an Islamic family. It is beneficial for a Muslim husband and wife to have children of their own, therefore there is no objection to using modern medical technology to that end. However, the means used must not violate Islamic tenets by using donated eggs or sperm: the husband’s sperm is used, but not that of a donor. Surrogate motherhood is not allowed because it also requires the intervention of a person outside the marriage.

Another example of contemporary ijtihad can be found in the field of finance. Islam prohibits the giving and taking of interest, therefore Muslims should avoid taking loans from ordinary commercial banks or investing their money in them. Islamic banking has evolved as a means of overcoming the practical difficulty of obtaining finance in the modern world without becoming involved in interest-based transactions.

Among the many modernist-reformist voices that have proposed to bridge the gap between the Qur’an’s extra historical, the transcendental value system of equal rights and its actual application in Muslim legal tradition riddled with discriminatory practices is the Sudanese jurist Abdullahi An-Na’im, a disciple of Shaykh Mahmoud Mohammed Taha (d.1985), founder of the Sudanese Republican Brothers movement. Taha’s approach to the problem, as outlined in his book, had been to differentiate between the Qur’an early (Meccan) message (tolerant and egalitarian) and it’s later (Medinan) message (seen at least in part as an adaptation to the socio-economic and political situation of the Prophet’s Medinan community).

An-Na’im has since developed his mentor’s general principles into a framework for the radical reform of Islamic law and legal institutions that invalidates the established historical institution of ijtihad in favor of a new “evolutionary principle” of Quranic interpretation; which reverses the historical process of Shari’ah positive law formation (which was based on the Qur’an’s Medinan verses) by elaborating a new Shari’ah law (based on the Meccan revelations). This modernist approach, which reflects a sort of revival of the beliefs of the early Muslim jurists in the close relationship between law and culture in Islam, denies all normative powers to the Shari’ah as presently formulated but maintains the essential validity of the concept.

The problem regarding the position and ongoing normative powers of the Shari’ah in contemporary Islamic societies has continued to exacerbate polarization between secularist and traditionalist points of view. Secularists have argued that the Shari’ah has lost its normative power and is no longer applicable. They have argued that the Shari’ah laws relating to business and economy are outdated; other laws, such as those regarding slavery, are no longer valid, and the remainder “is largely contrary to international human rights and individual liberty laws.”

In diametrically opposed fashion, Islamists are likewise focused on the normative power of the Shari’ah (as presently constituted) by upholding it in essentialist terms. This means that when the law and social practices diverge, it is the law that is a valid and social practice that must change in order to achieve conformity with it. The less society conforms to God’s law, the more urgent is the Islamists’ demand for change and purification. As exemplified by Sayyid Qutb (d. 1966), chief ideologue of the Muslim Brother in Nasser’s Egypt, Islamism has defined sovereignty largely within a framework of law and authority where the sovereignty of God is synonymous with the sovereignty of the Shari’ah within an Islamic state.

When Islamists, therefore, call for a “return of the Shari’ah” they do not mean to bring back the traditionalist fiqh (tainted by centuries of ulama-state accommodation), such as the Taliban regime has done in Afghanistan; rather, they envisage an alternative Shari’ah based on the Qur’an and, especially, the restoration of the Prophet’s Sunnah that prominently involves the building of a new state structure and new political institutions under Islamist leadership.

By contrast, when the traditionalists, especially now given a voice by conservative clergy and legal experts, call to restore the Shari’ah, their demand is generally for the restoration of Islamic fiqh to replace the legal norms and institutions that were created during the colonial period or by the post-colonialist nation-states. So far, only a few of the establishment’s religious scholars have used their professional credentials and legalistic expertise to develop innovative opinions within the legal methods of traditional fiqh. A prominent example is Yusuf al-Qaradawi, who arrived at new formulations of Muslim women’s social and political rights during the 1990s by way of the established fiqh: indigenous methods of law finding.

In addition, the general public has to some degree begun to participate in the civilizational debate on the role and meaning of Islamic law in their modernizing societies. By way of the new media, especially the new electronic means of communication, non-specialist Muslim individuals, including women and the young, are beginning to create what may perhaps one day turn out to be a groundswell of scripture-based individual opinions on legal issues that they derive largely from a personal study of the Qur’an.

Is the Shari’ah as a legal system now defunct? While there is a clamor by Islamists in the Islamic world for the restitution of the Shari’ah and an affirmation of its efficacy and eternal validity, Wael Hallaq, in his opinion, argues that the Shari’ah is “no longer a tenable reality, that is has met its demise nearly a century ago, and that this sort of discourse is lodging itself in an irredeemable state of denial.”

Although sympathetic to the desire of the Middle East to distinguish itself from the West, Hallaq is firm in his assertion that the concept of nationalism and the creation of modern nation-states have negated the possibility of living by any comprehensive system of Shari’ah. He supports his opinion by analyzing the nature of reforms currently underway that he refers to as the “cobbling together” of interpretations of Shari’ah borrowed from various historical legal schools and other legal-theological traditions. Spurred on by international pressure to create a body of laws that will adhere to the conditions of a modern constitution, lawmakers in the various nation-states are now creating hastily constructed legal templates that will satisfy both international organizations and popular ideologies.

The only way to achieve such a precarious balance is to adopt the most lenient laws offered by the various inherited legal traditions, laws that will receive the support of the population. The only sector of law maintaining any uniformity under these conditions, Hallaq argues, is personal status law. it may, however, be precisely the latter’s more Islamic uniformity, as opposed to the heterogeneity of the rest of state law, that will eventually serve to accentuate the larger legal system’s incoherence and thus contribute to strain “the intricate connection between the social fabric and the law as a system of conflict resolution and social control.”

The root of the problem, according to Hallaq, is the modern state control of waqf (the wealth amassed by centuries of private unalienable property contributions formerly administered by representatives of the clerical establishment), the loss of which has undermined the ability of Islamic schools of law, institutions, and officials to function independently of the political establishment and thus has destroyed their tradition of legal innovation and adjustment that informed the formulation and practice of Islamic law in the past.

We agree with the argument of Islamic modernists such as Fazlur Rahman, Abdullahi An-Na’im, Mohammed Iqbal, and Abdullah Saeed that the interpretation of the ethical-legal content of the Qur’an and Sunnah needs to take social change into account in order to sustain the close relationship between the primary sources (Qur’an and Sunnah) and the Muslim today. The Qur’anic interpretation up to now, which has been to a large extent philological, needs to give way to a more sociological and anthropological exegesis in order to relate it to the contemporary needs of Muslims today.

However, a search for acceptable methods in the modern period should not neglect the classical Islamic exegetical tradition entirely. On the contrary, we should benefit from the tradition and be guided by it where possible without necessarily being bound by all its detail. Contemporary scholars must be informed about the ways in which the texts have been interpreted throughout history. That understanding can be helpful in our formulation of new interpretations in the light of new circumstances and challenges.

Challenges and Opportunities of Business and E-Commerce under Islamic law

Internet closes the distance in the physical world. With the existence of the internet, the world is actually borderless. People can buy clothes, books, and electrical appliances through the internet and also can gather information and learn about other cultures and climates from the internet. With the development of the internet, it has not only become a way of communicating or information gathering but also of getting products sent to our home. This era is called the E-Commerce era. Many conferences and seminars have been held pertaining to e-commerce but only a few have brought up matters about e-commerce from the Islamic perspective. With the challenge to fill this gap, the thesis will highlight the framework of Islamic E-commerce (E-sale contract) and the challenges that Muslims would be facing.

In the world commerce industry, the way we communicate and do business has changed as a result of the impact of the internet. As we can see the changes are taking place rapidly in our daily life. We do not have to personally go to the hardware and supplies shops to buy materials required for building a house. What you have to do is to switch on your computer with an internet connection. While connected to the internet you are able to browse the online supermarkets and click on every single item that you want for the house construction in your virtual shopping cart. In a few days, all the items ordered through the internet will be delivered to your doorstep. What you must have are a debit/credit card number and a postal address.

Islamic business can be established as an amalgamation of business organizations that function under the guidelines of the Shariah and do not engage in any of the following activities.

- Operations involving Riba or Interest as it is commonly referred to as.

- Maisir or Gambling involving operations.

- Operations involving the manufacturing of non-halal products such as Pork or liquor.

- Operations involving gharar or elements of uncertainty such as those found in modern-day insurance banking.

According to Yusuf al-Qaradawi (a modern Muslim scholar from Egypt), there is no prohibition of trade in Islam in any circumstances other than those that involve the promotion or encouragement of cheating, exorbitant profiting, or the engagement in activities that are classified as haram.

The goal of Islamic business will be two-fold: maximizing the profit margin while ensuring social welfare maximization alongside.

Not only are trade activities the major economic activities at present, but they are also the main economic activities of our ancestors. The traditional way of doing trade however is changing rapidly with the introduction of the internet. Physically, the internet is nothing more than an unregulated network of computers mostly linked either by telephone lines or broadband connections. It is different from our traditional way of doing business or trade. The internet development is so rapid, that no business, conventional or Islamic, could afford to be left out in order to be able to compete in the free market.

Therefore Islamic businesses must take part in internet development to be at par with all other businesses. However, studies need to be conducted in the E-commerce area to adjust Islamic business needs in order to ensure that they are in line with Shari’ah guidelines.

There are three basic things that should be considered in Islamic e-commerce contract formation over the internet as well as the buyer, seller, and the product. They are offer, acceptance, and consideration. If all these things have been observed and implemented, e-commerce is permissible because the Shari’ah use Ibahah, which is a presumption in Shari’ah that everything is permissible in the absence of specific Qur’anic injunctions.

The basic principle is that something which is not forbidden is deemed to be lawful based on the maxim “lawfulness is a recognized principle in all things.” In other words, everything is presumed to be lawful, unless it is definitely prohibited by law.

Doing business according to the Islamic perspective is not difficult since it promotes justice for sellers and buyers as long as it adheres to Islamic principles. However, avoiding riba or gharar seems almost impossible for Islamic businesses since almost every transaction will directly or indirectly involve the riba elements. These are the major challenges that Islamic businesses have to encounter. The other two prohibitions such as Maisie and selling prohibited products are normally adhered to by Islamic businesses. Even though matter and selling prohibited products are deviant for Islamic businesses, these two prohibitions should not be ignored completely. They should be managed by Islamic businesses in order to achieve the goals of profit maximization and welfare or success maximization.

Gharar and riba are the two prohibitions that are ignored by Muslim businesses due to our own ignorance. Riba is interest or any addition resulting from the lending process. It is predictable that riba is widespread in the business system in any company including Islamic businesses as the conventional financial system survives from it. This situation would encompass the problems that an Islamic business would be facing in avoiding the prohibition of riba in order to uphold equitable economic justice principles under Islamic law.

Riba is clearly prohibited from the Qur’anic perspective:

“Those who devour usury will not stand except as stand one whom the Evil one by his touch hath driven to madness. That is because they say: ‘Trade is like usury,’ but Allah hath permitted trade and forbidden usury. Those who after receiving direction from their Lord, desist, shall be pardoned for the past; their case is for Allah (to judge), but those who repeat (The offense) are companions of the Fire: they will abide therein (forever)”.

The challenge for Islamic e-commerce in fighting riba would be choosing a payment and banking system which is Shari’ah compliant. This is important because the operational backbone of e-commerce is in its payment and banking system. In our present system, most of the domestic and international trades use conventional financial systems that are connected and related to riba.

So if Muslim entrepreneurs want to sell their products by e-commerce, they have to ensure that they do not become involved in riba transactions in their deposits, financing, and payment system. To avoid riba at any cost, Muslim businesses must ensure that they utilize the Islamic banking or Islamic financial system. The products which are currently offered by the Islamic banks are competitive with a product range covering deposits, financing, and other services.

Products such as Mudarabah, Musyarakah, and Murabah as we will explain further in the next chapter, are examples of the most common products of the Islamic banks. The support from the Islamic banker to Islamic commerce is inevitable and it is expected that Islamic bankers provide facilities that are on a par with the conventional system in terms of its services, range of products, and reliability.

Since the introduction of the Islamic banks, Muslims have had the opportunity to avoid unscrupulous conventional financial systems and use the Shari’ah-compliant financial system. With this opportunity, the development of e-commerce must abide by the Shari’ah prohibition of interest, and therefore the payment systems selected must also be Shari’ah compliant.

The next challenge is to avoid the gharar elements in buying and selling contracts. Numerous hadiths can be found on the subject of gharar and many of them refer to specific scenarios. A commonly cited hadith is that quoted by Imam Ahmad, Imam Muslim, al-Tirmidhi, Abu Dawud, Ibn Majah, and al-Nasa’i, all of whom do so upon the authority of Abu Hurayra that:

“The Prophet (P.b.u.h) prohibited the gharar sale”.

The Shari’ah established that in order to ensure fair dealings between parties in contracts, any case in which uncertainty leads to an unjustified enrichment in the contract is prohibited. According to Kazi Mortuza Ali in his paper “Introduction to Islamic Insurance”, Gharar can be found in all the business dealings in which a party involved in the contract has no perception or idea about what the party shall receive upon the conclusion of the bargain. Yusuf al-Qaradawi defines gharar as an action in which something is sold with clear incorporation of uncertainty and can be expected to lead to the generation of conflict or unjustified enrichment.

If gharar is to be avoided, the parties must ensure that

- the prices along with the subject of the sale are in existence and can be delivered,

- the specific characteristics of the items and the counter value can be established,

- attributes that are fundamental such as quality, quantity and delivery date are predetermined.

If any of these prohibitions, riba, and gharar, can be avoided along with other prohibitions, the Islamic business can achieve the two goals of profit and Falah (success) maximization.

E-commerce does have a place in the Islamic perspective; however, whenever it takes place, certain requirements of the Shari’ah should be complied with and adhered to. This is to ensure that the goals of the Islamic business, which are Falah and profit maximization, could be achieved. By achieving these goals the Muslim can be successful in business and also in the days of the hereafter. Falah maximization could be achieved by abiding by the Shari’ah and the four major prohibitions outlined are the prohibition of riba, Maisie, gharar, and of selling prohibited products such as pork.

On the other hand, profit maximization of Islamic e-commerce could be achieved by differentiating products, fair price, quality, and services offered to the customers through e-marking mix and networking. In adhering to Islamic principles, the Islamic business must have the products, full information or description about the products, and the ability to deliver the products. As far as e-commerce is concerned, it is permissible from an Islamic perspective as long as it abides by the Shari’ah guidelines. The Prophet (P.b.u.h), through his sayings and action, encouraged the form of trade that considers merchants to engage in honest trade so that they may be considered with Martyrs on the Day of Resurrection.

The Islamic Sale Contract

In the absence of a general theory of contract in Islamic law, the study of the e-sale contract should lead us first to begin with several observations and a deeper understanding of the traditional sale contract in general, and then consider the e-sale contract in particular. It is imperative to note that Qur’an and the Sunnah, in their dictation of Islamic Law, present general rules about the law of contract which is unique when compared to the laws of individual contracts. The Qur’an addresses rules pertaining to commercial contracts at over forty different instances. Aside from the specific verse on performing the contract, Quran 5:1, and the three on the necessity of keeping a promise, a few other verses also shed light on advanced commercial contracts dealing with selling and hiring.

The Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) himself was a merchant and engaged in commercial practice, however, he forbade some and permitted other activities in commercial practice. Most of these guidelines can also be found in the Qur’an and can therefore be considered to be nothing less than Divine Commands that are to be applied at all times. Other guidelines can be found in the Sunnah as well as in authenticated references dating back to the actions and words of the Holy Prophet.

However, the Muslim jurists from the four Islamic Sunni schools have devoted by far the greatest part of their scholarly writing to specific contracts such as the sale contract. Businesses in Islamic law are faced with the same set of financial challenges.

My confidence in the Qur’an and the traditions of Prophet Mohammed and all supplementary imperative alternates, the Islamic law will be wide enough to accommodate the needs of e-sale contract requirements, without however going against the general principles of Islam.

Prior to discussing the formation of the e-sale contract under Islamic law, it is essential to deal, in this chapter, with the general fundamental rules and principles governing the traditional sale contract. It is hoped that an exposition of these general principles and rules will assist in the clarification of the more detailed discussion on the formation of the e-sale contract under Islamic law which will follow later.

In Islamic law, there are various definitions of contract in general, and the sale contract in particular. The contracted word in Arabic (Uqud) covers the entire field of obligations, including those that are social (like marriage), political, and commercial, and also deals with the individual’s obligation to God (Allah). However, the most well-known definition of the sale contract, in particular, came in the initial contemporary establishment of Islamic law of obligations and contracts, Mejella al-Ahkam al-Adliyyeh article 103: “contract is an obligation between two persons or contractors about a lawful act in a good manner” or “exchange of offer and acceptance with real intention”.

However, if the contributions made by the jurists of different Islamic schools of thought were considered, it is observed that differing definition of a sale contract and it is dealt with much more widely in fiqh writings than other contracts. A sale contract for Abu Bakr al-Kasani, the Hanafi author of Badaa’i al-Sanaya (d. 587/1191), purports the exchange of a coveted article against another coveted article; such an exchange takes place either by words or by deed. For al-Kassani the binding effect of the sale contract and the conferring of immediate possession of the counter values intended to be exchanged are its two main effects. Muwaffaq al-Din Ibn Qudama, the Hanbali author (d. 620/1223), sees a sale contract as an exchange of property against another property conferring and procuring possession.

As we look at these early definitions, any definition suffers from an inherent inadequacy. Linguistically, words have different shades of meaning. Technically, terms and expressions evolve and frequently change over the course of time, albeit imperceptibly. Therefore, we find any definition involves a high degree of abstraction which, when applied to the instances meant to be covered by it, may fail to achieve its intended ambit. At best, a definition may be considered as a proposition for the explanation of the scope, or an initiation to the exposition, of the subject concerned. This approach to the definition of the sale contract is perhaps more suitable to a jurisprudential treatment of the subject than to a normative formulation of it.

As a result, we may prefer to define the sale contract the way some authors define it, as the relocation of possession of legal goods for a set price (money or other assets), with both standards established and conveyed without delay. However, impediment in reimbursement of a counter-value is considered a unique case in Islamic law. The title of both counter values transfers immediately at the time of sale, even if actual payment or delivery of property is delayed by stipulation or otherwise.

In the Islamic legal system, like other legal systems of the world, certain formalities and substantive elements are essential for juristic acts to become legally binding on the parties. Classical Muslim jurists developed a clear concept of juristic acts which produced a legal effect on all commercial contracts. The sale of contractual transactions, whether written, unwritten, or by correspondence, constitutes the vast majority of juristic acts. That being so, Muslim jurists of the four Islamic schools stipulated a clearly defined idea of the conditions and requirements of validity for a binding sale contract.

These essential conditions and requirements of substantive and procedural law now provide the criteria for the void, valid, binding, and enforceable elements of all contracts in general and the sale contract in particular. Muslim jurists from these schools laid down a set of criteria for distinguishing between essential conditions on which the valid conclusion of the sale contract depended, and those which are regarded as less fundamental and which might affect its binding force on only one of the parties in the sale contract.

Furthermore, Muslim jurists went further and spoke of the non-existence of goods in the sale contract as a radical form of nullity under which the contract was considered as if it had never taken place. They also recognized, in contrast to the above category, contracts the effects of which were merely suspended (mawquf ala al-ijazat), depending on the choice of the party whose intention was not validly expressed, and for whose protection the nullity was prescribed.

Principle of Freedom in the Sale contract

Islamic scholars from different schools seem to differ in their opinions regarding the degree of freedom contractors have to conclude a contract. However, a closer examination of their opinions reveals that they agree on the major rules and principles relating to the freedom of contracts and they only differ on some details. The first view, which is the view of the Hanbalies and Malikies, explains that contractors are totally free to conclude whatever they wish, provided that it complies with Islamic rules and principles. This view believes that the root principle of contracts in Islamic law is the freedom of contracts except where they are explicitly prohibited by a provision or an injunction. Proponents of this view base their argument on some provisions from the Qur’an, and Sunnah and reasoning. Of particular importance here is:

“O ye who believe, fulfill pledges….”

“… but Allah hath permitted trade and forbidden usury.”

“O ye who believe! Eat not up to your property among yourselves, but let it be amongst you traffic and trade ….”

“How can men stipulate conditions that are not in the book of Allah? All conditions that are not in the book of Allah are invalid, be it a hundred conditions. Allah’s book is more trustworthy and his conditions are more worthy to obey.”

The second view is that of the Hanafis and the Shafi’ies, which have established a middle course concerning the issue of freedom of contracts. Their handling of the subject of freedom to include conditions in contracts shows, as will be seen later, that they are, in principle, not as liberal as the Malikies or the Hanbali.

Regarding the conditions which can be included in sale contracts, jurists categorize the conditions that can be valid and legally sound as follows:

The Stipulation Inherent in the Nature of the Sale Contract (al-Shart al-ladhi Yaqtadih al-Aqd)

The requirement of a circumstance that pertains to the nature of the sale contract is superfluous. Thus, to affix a section to a trade contract according to which the purchased object eventually becomes the property of the buyer is tautological, as this stipulation follows without a doubt from the fundamental characteristics of sale as such. Also, similar common attributes of sale – such as compensation of the price and taking ownership of the sold article – the Hanafi and Shafi’i schools also consider conditions from the explicit nature of the sale. The condition that is inherent in the nature of the sale contract does not invalidate the sale contract.

Thus if an object is bought on the condition that he acquires its ownership, or if an object is sold to be paid a price for, or if an object is bought to take possession of it, or if a garment is bought with the intention to wear it, the sale is permitted since the sale requires that these supplementary conditions are met even if they are not stated. It is imperative to note that their consideration as conditions does nothing more than establishing the nature of the contract and does not make the contract invalid in any manner.

The Stipulation Appropriate to the Sale Contract (al-Shart al-Mula’im li al-Aqd)

All the Classical Islamic Schools allow no more than two natures of clauses to be attached although the condition to do so is not mandatory in the terms of the contract. In fact, at this point, it becomes essential to mention rahan and Kafala, also referred to as the pledge clause and suretyship clause that exist in concordance with the purpose of the sale and the legal structure. Accordingly, pledge and suretyship are admissible stipulations under all Sunni Islamic Schools.

The condition that is not inbuilt in the transaction, but is fitting to the contract, does not annul the sale contract as it is in accordance with its necessary connotation and verifies it; so it enjoins the requirement which is a prerequisite of the transaction. In the event that one sells an item on the stipulation that the consumer pledges security (rahan) as a counter-value to the value, or on the stipulation that the buyer has an underwriter (Kafil) who is willing to stand as safekeeping for the value: in these cases, the sale is legal and is permitted by virtue of juristic predilection.

Analogical inference (Qiyas) restricts the sale because any condition which is in contrast to the primary contract serves to annul it. Pledge and suretyship clauses are superfluous to the principal terms of sale and therefore have an annulling implication on the contract. However, these stipulations have been juristically opted to declare because though officially different from the primary terms of the contract, they, all the same, agree with its indispensable denotation: the assurance of security as a counter-value to the worth is a consolidation of the value and the very same concept holds for suretyship.

Both the conditions strengthen the right of the seller and therefore do not nullify the sale contract. Nevertheless, the sale contract is permissible since the idea of the pledge is to receive a return: its legal approval lies in its confirmation of the right to return, which verification is a specification that is fitting to the sale contract. The editing of legal logic in the course of obliging practice results in considering the pledge of security and suretyship of an underwriter clause as officially valid.

The Stipulation that is Customary Practice (al-Shart al-ladhi fih Ta’amul)

All the four Islamic Sunni Schools agreed that under the allowable type of stipulation styled “the conventional stipulation” such clauses being a constituent of local custom (Urf) are allowed to be lawfully obligating despite the fact that they are peripheral to the fundamental terms of the sale contract. Also, article 321 of Murshid al-Hayran has allowed this kind of stipulation, so a condition which is neither hinted toward in the primary contract nor suitable to it, but which is an ordinary application, is permissible.

This exists if one buys a sole on the stipulation that the vendor fixes it to the shoe. Reasoning by analogy (Qiyas) Hanafi jurists do not allow such a requirement as the added clause is not necessary by the principal contract and is of advantage to only a single party, as in the following section. As a result, the clause annuls the contract, similar to the case in which one buys a cloth on the stipulation that the vendor tailors it into a shirt.

The Stipulation of Benefit to One of the Parties

The Maliki and Hanbali schools provide the text-based reasoning for the rejection of the Hanafi scruples about annexed clauses that profit one of the parties involved in the sale contract, and, derivatively, for the freedom of stipulation. That the Maliki and Hanbali ruling with regard to the sale contract conditions is formulated in mindful resistance to the Hanafi is apparent from Ibn Qudama’s rejection of the Hanafi ruling in opposition of added clauses that benefit any one of the parties involved in the contract. Therefore, jurisprudence in accordance with Maliki and Hanbali validates similar sale contracts whose annexed clauses were evaluated for their authenticity by Hanafi jurisprudence as invalidating the whole contract. The Maliki and Hanbali jurisprudence affirms

“The legitimacy of the stipulation of an additional benefit by one of the parties such as inhabiting the house for one month before its delivery to the buyer. Also, the sale is valid if the buyer stipulates an additional condition to his benefit in the object, such as the transport of the firewood or the tailor of the cloth….”.

The advocates of this opinion claim that:

“It is not true that the Prophet (P.b.u.h) forbade the sale containing a stipulation. What he forbade was the sale containing two stipulations: he did allow the sale contract with the single stipulation.”

The Maliki and Hanbali jurisprudence meets the Hanafi opposition through a multifaceted appeal to the authority of master conservatives. The Hanafi School’s Hadith is canceled out in two aspects: first is the absence of credible hadith collections; second is the adherence to a version of the hadith according to which only sales with two annexed clauses are forbidden, the sale contracts with one additional condition – opposing to the Hanafi ruling – are considered lawfully obligating. The Hanbali reaction to Hanafi conservatism on condition application on the two main causes of constraint:

- the Prophetic saying in opposition to “sale with annexed stipulations”; and

- the addition of gainful prerequisites under illegal gain (riba).