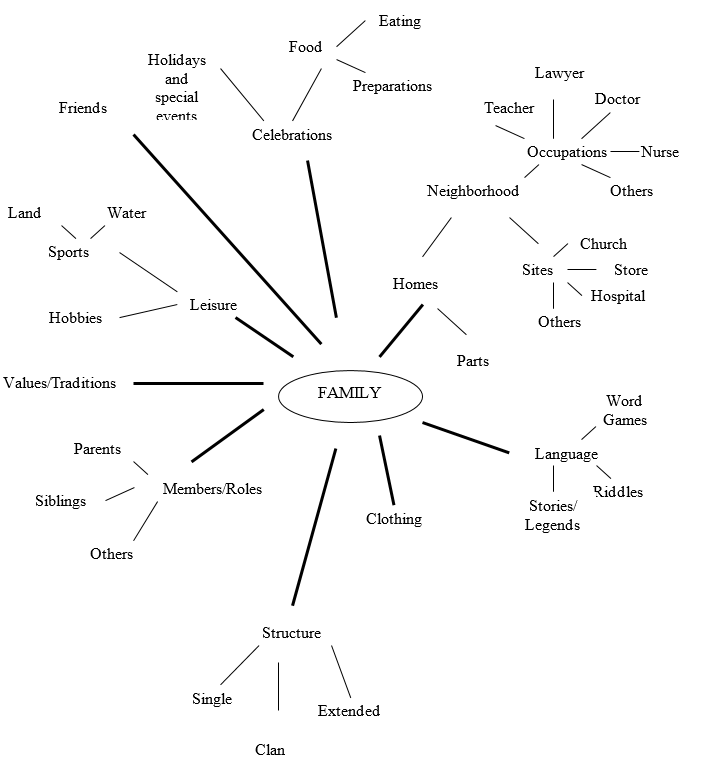

Concept Map: My Family

The foregoing concept maps show just how rich the early childhood curriculum can be and how wide the spectrum of learning a child can explore. It illustrates an integrated curriculum that relates concepts to each other as well as skill areas. Littledyke (2008) has defined integrated curriculum as such: “Integrated curriculum thus refers to the use of several different strategies across several different domains and encompassing project and process approaches for holistic learning and development designed to support meaningful learning for children” (Littledyke, 2008, p.21-22). In the concept map, everything branches out from the main concept or theme which is family.

This theme is of interest to children because it is their first social circle and is very relevant and meaningful in their lives. Basically, its learning about people other than themselves. Since family members are the significant people in children’s lives, the theme will evoke a great deal of interest in the children.

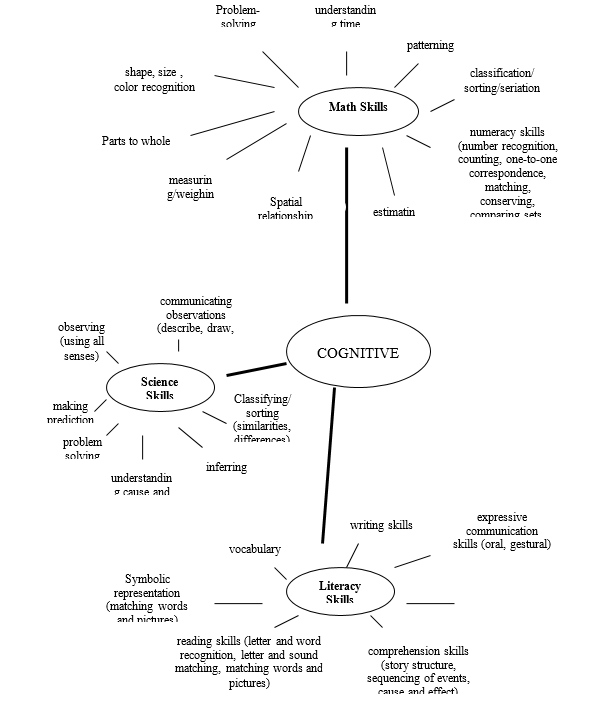

The second illustration shows the cognitive skills that may be developed from the concepts and activities designed in the integrated curriculum. The figure focuses on math, science and literacy skills. These skills may overlap across subject areas as well as developmental domains.

The main concept branches out to various subconcepts all related to family and to other subconcepts. If each subconcept will be thoroughly studied, then the concept map can be used for a long term or even the whole school year depending on the age level of the children and the depth of investigation into each subconcept.

Justification of Concept Map

There are many opportunities for learning using the concept of family. The teacher may even engage the active participation of the children’s family members In terms of literacy skills, there is a multitude of storybooks on family that may be read in class. Children may also create their own storybooks with their families. It can be a weekend assignment assigned by the teacher where each page can highlight a separate family member – with pictures or words contributed by that family member. When the child brings it back to school, he or she may share and “read” it in class.

One project that may be done by all the families in class is a Storybook Chain. The class begins the story with the first page, with the children contributing the drawing, introducing the characters of their choice, setting and plot and giving it a title themselves. Then, turn by turn, each child will bring it home for their families to do a page or two to contribute to the story. The culminating activity can be a Family Reading Night when all the families will be invited to class for story readings by some parents, and the highlight, of course will be the reading of the completed Story Chain so all the families will know how the story turned out. Such a collaborated effort will engage children’s interest in their own literature and motivate them to read and write more of their own.

Numeracy skills may be learned with counting and comparing the numbers of family members per family in class. Charts may be created on how many girls and boys each family has, or what their favorite foods are and later on compare the “statistics”. This may also extend to other subconcepts like the home, counting how many windows or doors each home for each family has. The family members, their roles and their home may be used as resources for math lessons.

Activities such as those previously given are examples from a preschool program that adheres to the constructivist theory. This stems from theories of Piaget and Vygotsky. Chaille (2008) argues that constructivism believes that children are constructing knowledge on their own and the learning environment considers and respects that. “In a constructivist classroom, children are constructing an understanding that they are building their own theories and constructing their own knowledge through interaction with a knowledgeable adult and other children” (Chaille, 2008, p. 5). It has much value in helping children use their minds well. Constructivist curriculum helps promote thinking, problem-solving and decision-making in children making them flexible and creative thinkers (Cromwell, 2000).

Constructivist programs do not adhere to totally teacher-directed strategies, as most behaviorist schools do. This way, when children create their own learning through hands-on experiences, they retain concepts better and are more motivated to gain and develop skills. Schweinhart & Weikart (1999) presented studies that evidenced the long-term benefits of child-initiated learning in early childhood programs, as such activities help them develop social responsibility and interpersonal skills as they grow up.

The concept of family entails family participation in the preschool program, much like the approach followed by Reggio Emilia schools (Fraser, 2000). Teachers and parents can collaborate in coming up with age-appropriate activities for the children. The curriculum may also include community involvement as the children learn about family roles in the community such as what their parents’ jobs are and how they help the community.

Consistent with constructivist philosophy is the project approach which can be very appropriate to apply to this curriculum. Projects are sets of activities with ideas mostly contributed by children and followed through and supervised by the teacher. It truly takes the children’s lead in investigating matters that interest them. “Projects provide experiences that involve students intellectually to a greater degree than the experiences that come from teacher-prepared units or themes. It is the children’s initiative, involvement and relative participation in what is accomplished that distinguish projects from units or themes” (Helm & Katz, 2000, p. 2).

For example, on this theme on family, home is a subconcept that can be investigated in a number of ways. It can begin with the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears which links it with the numeracy concept of number 3 and its quantity. The story moves the family around the different rooms in the house and the teacher can have discussions about each part (i.e. bedroom, what we do there; kitchen, what do we see there, etc.).

A project map may be created by the teacher with the students, as to what they want to know about homes and children will post all possible questions and points of inquiry like parts of the house, different types of homes, people who build houses, etc. and plan out activities to investigate such questions. A Home visit may be done to some homes of the students in collaboration with the parents. A field trip to a house being constructed may also be an activity and builders may be interviewed as to what they do and what materials may be used. Back in school, the children may come up with a “housing project” building homes out of cardboard boxes and other materials. The whole process may be documented by the teacher with pictures and video and anecdotal records to present to the children and parents upon completion of the project.

This curriculum is envisioned to be implemented in an environment organized by teachers to be rich in possibilities and provocations that challenge children to explore, problem-solve, usually in small groups while the teachers act as keen observers or recorders of the children’s learning. Teachers get to balance their role by sometimes joining the circle of children and sometimes objectively remaining outside the loop (Pope Edwards, 2002).

Teachers are on hand to provide assistance or further challenge children’s thinking to push them to optimize their potentials. They also observe children’s behaviors to see which of their needs need to be met (Lambert & Clyde, 2000) and design opportunities to address such needs either through the curriculum or through their social interactions. Billman and Sherman (1997) recommend teachers to note down their observations in their journal so they can review them and adjust accordingly the curriculum to better suit the developmental needs of their students.

At one glance, the integrated curriculum shows the coverage of what the children learn in school. It advocates natural learning, as it follows children’s interests and not impose the concepts that they need to learn. It follows that the skills they learn become meaningful to them, as it sprouts from their own interests. It also gets to touch on multiple subject areas and work on various developmental domains at a time.

For the teacher, an integrated curriculum is a good planning device that offers much flexibility. If the children leans toward another way other than what the teacher had expected, the integrated curriculum quickly guides her as to how to integrate it to a related concept so the flow of learning is not disrupted.

The richness of the integrated curriculum cannot be underestimated nor overemphasized. It is a great tool to help teachers and a great way to maximize the learning potentials of their students.

References

Billman, J. & Sherman, J.A. 1997, ‘Methods for recording observations of young children’s behaviour’, in Observing and Participating in Early Childhood Settings: A Practicum Guide, Birth Through to Age Five, Allyn & Bacon, Boston, M.

Chaille C. 2008, ‘Big Ideas: A Framework for constructivist Curriculum’, in Constructivism across the Curriculum in Early Childhood Classrooms, Pearson Education, Sydney.

Cromwell, E.S. 2000, Nurturing Readiness in Early Childhood Education: A Whole-Child Curriculum for Ages 2-5, 2nd edn, Allyn & Bacon, Needham Heights, MA.

Fraser, S. 2000, Authentic Childhood: Experiencing Reggio Emilia in the Classroom, Nelson Thomson Learning, Ontario.

Helm, HJ., & Katz, L. 2000, ‘Projects and Young Children’, in The Project Approach in the Early Years, Teachers College Press, New York.

Lambert, E.B. & Clyde, M. 2000, ‘Program planning for 3-5’s: A spherical framework’, in Rethinking Early Childhood Theory and Practice, Social Science Press, Katoomba.

Littledyke, R. (2008) Early Education Philosophy and Practice Topic Notes. University of New England.

Pope Edwards, C. 2002, ‘Three Approaches from Europe: Waldorf, Montessori and Regio Emilia’, Early Childhood Research and Practice, Vol 4, No.1. Web.

Schweinhart, L.J. & Weikart, D.P. 1999, ‘Why curriculum matters in early childhood education’, in Annual Editions: Early Childhood Education, ed.K. Menke Paciorek & J. Huth Munro, Dushkin, Guilford, Conn.