Introduction

According to Amaral and Larsen (2003, 99-161), when dealing with tort actions, government regulations, and contracts, lawyers are more successful if they have ample knowledge of economics. Heyne (1999 199-265) puts across that economics for lawyers is the most essential tool in understanding the economic basics of law. It determines major market issues such as the legislation’s social cost enforcement below the market prices, compensation, and non-competitive prices among others. Just recently, the UK government introduced Securing a Sustainable Future for Higher Education Brownies Report concerning higher education recommendations in England (Scott, 2000 145-178). Among the recommendations put forth include: a free market for the undergraduate education in social Sciences, Arts, and Humanities, enhancement of students’ choice which is believed to increase the quality of education, a financial plan that pays student’s learning costs upfront on their behalf, collects payment through the taxation from students and provides students with living costs money, replacement of current higher education bodies such as QAA with Higher Education council (HEC) in order to protect the public interest in terms of offering explanations on taxpayer’s expenditure and provided clinical training programs. The report has aroused a lot of mixed reactions that have driven most economic lawyers to carry out an analysis of the efficacy of the report in regard the market is successful or not (Machin and Vignoles, 2005 178-231).

Most of them are inclined into believing that the recommendations put forth provide no economic efficacy, are inefficient and the Higher Education Learning institutions’ (HELs) market should be regulated. Owing to that market is the backbone of any successful enterprise and the basis of major success determinant functions such as sales increment, profit maximization, intelligent decision making, risk minimization, and analysis of the profitability of the product in the given market, we must carry out an analysis of whether the Brownie’s report will enhance economic efficiency or deter it with a focus on how the recommendations put forth are going to function in the current market ( Enders and Jongbloed, 2007 97-134).

Absence of a good market

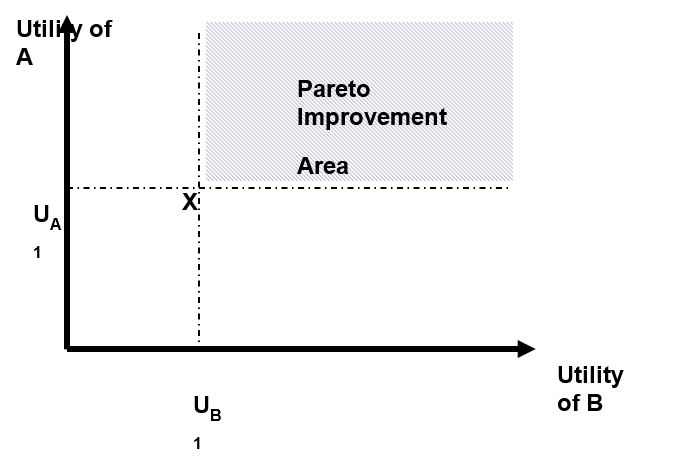

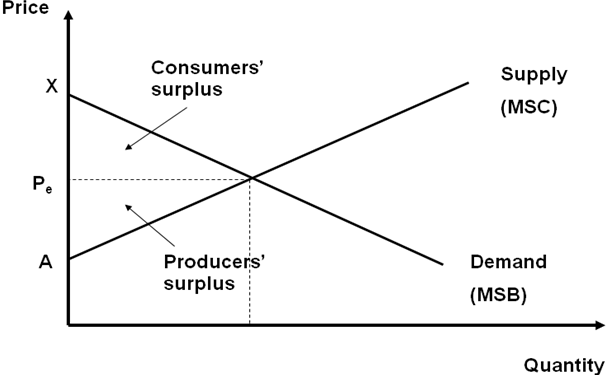

A good market is one that offers Pareto optimality whereby consumers’ consumption externalities are not allowed and producers’ production externalities are not allowed either. This implies that the resources available should make parties accrued to benefit better without worsening the state of either party (Gough and Scott, 2007 111-187).

Consumers (no consumption externalities)

MSB=MB=p

Producers (no consumption externalities)

P=MC=MSC

Hence, MSB = MSC

However, the recommendations put forth raise major questions as to whether the recommendations put forth will increase the market capability or decrease it.

The ‘growth’ of research

It has been noted that higher education state investment will be cut by 40%. Humanities, social sciences, and arts will no longer receive substantial support from the government while mathematics, technology, science, and engineering support will be increased. The report advocates for a free market for humanities, social sciences, and arts whereby there will be no economic regulation and intervention by the government. Research growth is usually an academic objective and should be encouraged by the government in order to exploit the R&D benefits, particularly from the higher learning institutions. However, a free market implies that the institutions will be driven to seek or accept funding from diverse sources and mostly on a marginal cost basis. As McBurnie and Ziguras (2007 156-199) point out, there will be market failures (MSB ≠ MSC) which will be characterized by the absence of consumer’s consumption externalities not leveling with producers’ absence of production externalities.

Market Failure: MSB ≠ MSC

Consumers (no consumption externalities)

MSB=MB=P

Producers (no consumption externalities)

P=MC<MSC

Hence, MSB < MSC

Rapid growth in activity and project funding in arts, humanities, and social sciences will outstrip the investment level in core research infrastructure. This will lead to decaying infrastructure and consumption versus investment imbalance which will in return lead to market failure (Ippolito, 2006 21-98).

Iacobucci and Tuohy (2005 123-156) state that the market is not at Pareto optimality or equilibrium to social optimum if a move from the market equilibrium to the social optimum will cause the third parties to gain much that the producers and consumers. In order for the funding parties (third parties) to benefit from the funds they give, they will demand knowledge transfer in humanities, social science, and arts in terms of testing, advisory services, intellectual property exploitation, and contract research. Even though this portrays a picture of economic contribution and a potential income source coupled with other benefits, most higher learning institutions are not well equipped or designed to manage such activities which need a managerial and financial environment equal to that of a commercial business in terms of disinvesting in staff, risk-taking, investing in services and rapid response.

As put across by Office for Budget Responsibility (2010, 122-178) such activities will add little or no financial security and will only pose new financial risks that cannot be easily mitigated by the institutions. This implies that the party’s funding (third party) will benefit more in terms of knowledge transfer, while the students (consumers) and the institution (producers) will lose in terms of the decaying infrastructure and financial risks respectively.

A state Policy approach that negatively simulates market outcomes

Almost all individuals equate the marginal costs to the benefits in order to respond to the outside market in reference to the legal rules provided. Hence, all legal rules should induct should microeconomic principles in order to enhance wealth maximization. The Coarse Theorem principle states that when the transaction costs are at zero, resource allocation is independent of the distribution of the property rights. This implies that the law cannot determine the output composition and resource allocation should be obtained irrespective of the state in which the law is to enable institutions’ efficacy. This means that at zero transaction, the exchange taking place should be mutually beneficial (there should be no strategic behavior, competitive market, wealth effects, costly court systems, and no profit maximization). However, there seems to be no autonomy between the states and the high learning institutions in the recommendations as the policies put forth cannot be maintained by the institutions themselves. The repayment of the students’ upfront cost which might amount up to 60,000 pounds is expected to be 25-30 years and after the 30 years, the government will write off any outstanding balance. The recommendations put forth require that the learning institutions contribute to meeting the costs incurred in learning. The government expects these institutions to collect all the money chargeable up to £6,000, and in return pay a levy on income from these charges so as to cover the government’s expenses in its quest to provide students’ upfront finance. Even though paying the levy fee will ensure that the institutions are committed to the project, it is likely to lead to the deferral of necessary spending in some areas.

This will also incur extra costs for the higher learning institutions in paying the levy fee; costs that might never be recovered. If the levy fee is not repaid by the students for longer periods, the financial stability of the institutions will be affected and strategic planning will become difficult as a distortion of the institution’s priority (inclining them to pay levy fees) takes place. This might further increase pressure on the physical infrastructure such as equipment, Institutions rationalization (merger or closure of institutions), and increase the student: staff ratio which might put pressure on the staff and make it hard for the institution to recruit and retain students. This will eventually lead to the closure of the academic departments or institutions and as we have seen, it will be against the common and widely used (theorem) economic theory whose objective is maximizing profit.

Market forces

In higher education institutions, market forces are not only relevant to the student but also to institutions’ competition for research contracts, staff, commercial contracts, government investment, and special initiative funds (UNESCO, 2002 189-202). Basically, if institutions are exposed to market risks and opportunities, they must be quite autonomous to enable them to respond promptly. Most Higher learning institutions are competing to attract overseas students to earn income and to make this possible; Lord Browne’s report is planning to counter the higher education demand by funding everyone with the potential of benefiting from HE. When there is demand, people have the desire to own something, the ability to pay, and willingness to pay.

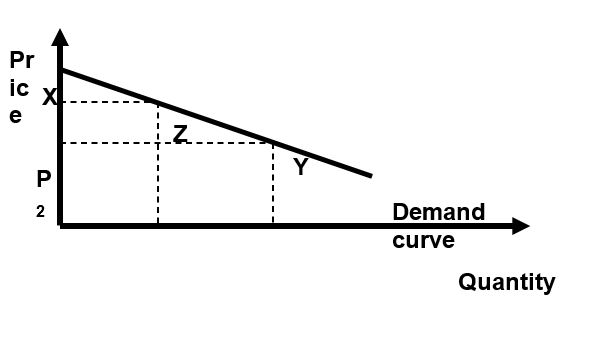

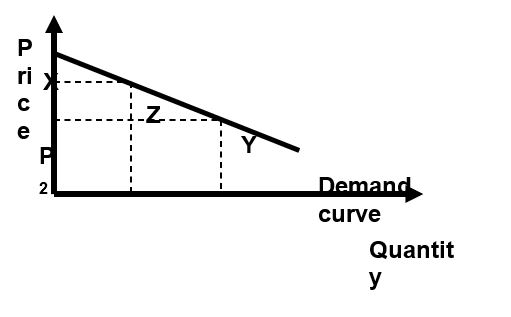

Number of student (decrease as higher education institutions offer affordable education that attracts lots of students)

Supply of qualified professional staff (decrease due competition of competitive staff by higher learning institutions)

According to Brown and Jones (2007 77-111), full funding of students (low cost education) is likely to attract more students. However, since most institutions are competing for competitive staff, there will be diminished marginal utility as qualified personnel decrease due to the huge number of students and competition involved. In most cases, most qualified or competitive staff will end up in private institutions where the there are attractive remunerations. Education and Skills committee (2007, 99- 134) notes that this will in return cause the number of students enrolling in higher education institutions to decrease as more will opt for private institutions (substitutes) whereby students versus the staff ratio is at equilibrium and quality education is likely to be given. Since higher academic institutions must align with academic aspirations and incentives, all higher academic institutions are inclined into adopting similar strategies at the expense of the desirable strategies. Webber (2006, 156-180) makes it clear that the market does not protect stakeholder’s interest in situations whereby there is absence of real competition (market failure). Hence, since they cannot rely on competition, they have to rely on a government that does not sufficiently fund them or provide them with financial incentives that can enhance effectiveness and efficiency.

Student choice and high quality education

As Brownies report puts it, catering for the students’ choice is likely to increase the quality of education. However, as The Stationery Office (2007, 79-156) outlines, students have different interests, needs and all the stake holders are different. This implies that student choice is not a prerequisite for high quality education. This is because for the students’ choices among them which are different learning styles to be met, students need to cooperate between with the staff. This way, the staff will understand the learning problems experienced bys students and jointly propose solutions that can work for all the stakeholders. According to Department for Education and Skills (2007, 102-156), this simply means that concentrating on the student choice without giving considerations to the staff choices who work jointly with the students in order to deliver high quality education will not be increase education quality.

Recommendations

The growth of research

To enhance the growth of research and mitigate factor hindering it, a good market that offer Pareto optimality is necessary. Jones and Evans (2008, 112-167) recommend that actual compensation be an ethical issue whereby gainers can compensate losers and remain at an advantaged position.

Schaltegger and Bennett (2009) state that an institution is financially sustainable if, in all its processes, it manages to recover all of its economic costs and invest in infrastructure to an extent that it can maintain its future productivity required in delivering its strategic plan. To attain Pareto optimality, institutions need to be financially stable through independent means such as investing sufficiently enable them to sustain their productive capacities, having strategic plans that will guide their investment and help them make decisions, avoiding funds that are below the institutions’ costs of activities and most importantly, know economic activities cost, activity portfolio, and project management in order to recover costs incurred. Freed, et al. (2002, 119-199) further suggest that institutions should collaborate and also form strategic relationships with other institutions in sharing, facilities, equipment, and staff teams. The structural collaboration will help institutions respond to the diseconomies of scale while a strategic alliance whereby legal joint ventures or informal associations are formed will enable institutions to combine their market profile and strengths in creating strong entities that offer higher quality services, avoid funds and push for policy reforms that will ensure that there is minimal government interference in terms of accountability and more help in terms of funds. This will ensure that the students, schools, and the government equally benefit from each other to ensure Pareto improvement.

New Policy enactment

As we have seen, higher education institution needs cannot be accommodated by the recommendations put forth in the report. This is because of the rapid student enrollment that has taken place as a result of core funding which in return has resulted in the decline in institutional infrastructure investment. Nevertheless, they are exposed to increased market pressures as we have seen above, and therefore, they need to differentiate themselves in order to succeed in a competitive market. According to Dill (2010, 123-189) policies must broaden up in terms of funding the institutions whereby there should be efficiency and collaboration gains that will encourage great market and commercial response and make students contribute more financially. It is also clear that government needs the institutions to aid them in achieving economic and social goals such as increasing accountability. Issues such as overtrading risks, living past investment, and financial viability place institutions’ reputation and education quality at stake. Policies such as diminishing state funding will enable institutions to gain much greater autonomy and manage to mitigate their risks (Bach, Haynes, and Smith, 2007 117-183).

Market Strategy

Brown (2010 187-207) points out that to counter the market forces and respond to external demands and needs, Institutions should not only concentrate on being supply-led in terms of what the staff will provide or the services they will offer but also on how to recover the cost incurred in the services given. As Johnstone and Marcucci (2006 120-170) say, if institutions need to counter the external market challenges such as excessive demand and supply, they must have a marketing strategy that will enable them to carry out market analysis, define market strategies, price their services and goods, and manage their portfolio. For instance, if institutions decide on proving low-cost education and enrolling more students, they should also decide on sourcing more infrastructure and qualified personnel in order to deal with the huge educational demand brought about by affordable education. Teixeira (2004, 89-123) notes that institutions should also be careful in giving grants to ‘everyone’ who can benefit from them. This implies that most people are likely to enroll for the university and this will make higher education institutions seem ‘cheap’ and easily be translated by the public into ‘poor quality. Guruz (2008 167-190) says that if the cost of education is well priced, the demand and supply of school enrollment and professional staff will be leveled and the market will be at equilibrium as shown below:

Income generation

Most institutions increase their income through funding and hence, most institutions succumb to financial crisis. To avoid this, Kretovics and Michael (2005 205- 247) advocate income generation from diverse sources such as knowledge transfer activities (such as academic related activities), fundraising and through the sale of their spare capacity such as conferences. Kogan (2000 178-195) says that in order to make this effective and efficient, higher learning institutions and the government should know that even though the purpose of the higher learning institutions is to promote the institutions interest and objects, the interest are also connected to the performance of the institutions and hence, income generation which is a major way of boosting the performance of the institutions should be put into consideration. According to Barr and Crawford (2005, 111-156) HEI’s should also know that for them to be successful at income generation activities, they should have a commercial approach aligned with the academic strength and therefore, strategic management that will avoid difficulties and tensions such as the institutions ability to offer an urgent response to challenges will help to maximize potential benefits and reduce risks.

Staff choice conjoined with student choice and high quality education

Brockbank and McGill (2007 123-167) note that the staff choice should also be considered in order to enhance high quality education. Knappand Siegel (2009 189-217) puts across that teachers want to have a better understanding of the students, share their knowledge with them and be flexible and free in terms of learning structures and time. According to Corver (2005 145-199), staff choice will foster the responsibility of teachers to the students, improvement processes, positive attitude and mutual assertiveness between the students and teachers with the aim of improving the quality of education. Hence, a student centered approach rather than a student choice approach should be used to ensure that there is quality education as Patil and Gray (2009 219-134) enforces.

Conclusion

Fry (2009 219-267) puts across that Higher learning institutions are formed with the basis of offering social welfare. However, the report indicates that the recommendations put forth in Brownie’s report do not offer a good market with Pareto optimality and therefore, the recommendations do not cater to people’s social welfare. This will result in the encouragement of third-party funding which will prompt the institutions to act commercially and place them under financial risks while at the same time; students will have to study under decaying infrastructure. The theorem principles advocates for the maximization of joint profit (Köhler and Huber, 2006 198-219). However, as we have seen, the state which plays a major role in running the institution subjects the institution to pay a levy fee for the upfront costs paid to the students whose re-pay guarantee is unpredictable hence risking the financial stability of most institutions. Allowing anyone who can benefit from the funding eligible for university entry is interfering with the student’s choice which the report claims to support. This will attract more students but at the same time, most students will opt for other learning institutions as low-cost education available to everyone is likely to be interpreted as cheap. Nevertheless, this will attract a lot of foreign students who are likely to benefit under the low cost while the UK students lose as professional staff shift becomes insufficient (shift to cater for a large number of students).

However, we have seen that all these problems can be catered for by regulating the market. Parent optimality can be enhanced if actual compensation where gainers compensate losers is possible. This can be achieved by letting the institutions function independently from the State interference in terms of investing freely. Collaborating with other institutions and forming strategic alliances will aid the institutions to respond to scale diseconomies and seek actual compensation from the government in terms of funds and minimal interference. Since most institutions have taken a commercial approach, policies should be enacted for the stakeholders to contribute to enhancing the success of the institutions. Moreover, new income sources should be exploited to avoid third-party funding overreliance and mitigate financial risks while a well-structured market strategy to respond to market forces and external demands and needs should be put in effect. All this will go a long way in eradicating the shortcomings of the recommendations put forth (Butler, 1998 145-278).

Reference List

Amaral, A and Larsen, I.M. The higher education managerial revolution? London, Springer, 2003.

Bach, S, Haynes, P and Smith, J.W. Online learning and teaching in higher education. London, McGraw-Hill International, 2007.

Barr, N.A. and Crawford, I. financing higher education: answers from the UK. London, Routledge, 2005.

Brockbank, A. and McGill, I. Facilitating Reflective Learning in Higher Education. London, McGraw -Hill International, 2007.

Brown and Jones, E. Internationalizing higher education. London, Taylor & Francis, 2007.

Brown, R. Higher Education and the Market. Taylor & Francis, 2010.

Butler, H. Economic Analysis for Lawyers. Carolina, Carolina Academic Press, 1998.

Corver, M. Young participation in higher education. London, HEFCE, 2005.

Dill, D.D. Public Policy for Academic Quality: Analyses of Innovative Policy Instruments. London, Springer, 2010.

Education and Skills committee. The future sustainability of the higher education sector: international aspects, eighth report of session 2006-07, Vol. 2: Oral and written evidence. London, The Stationery Office, 2007.

Enders, J and Jongbloed, B. Public-private dynamics in higher education: expectations, developments and outcomes. Salt Lake City, transcript Verlag, 2007.

Freed, M.N. et al. The educator’s desk reference (EDR): a sourcebook of educational information and research. London, Greenwood Publishing Group 2006. London, Springer, 2002.

Fry, H. A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education: enhancing academic practice. London, Taylor & Francis, 2009.

Gough, S and Scott, W. Higher education and sustainable development: paradox and possibility. London, Routledge, 2007.

Great Britain: Department for Education and Skills. Department for Education and Skills departmental report 2007. London, The Stationery Office, 2007.

Guruz, K. Higher education and international student mobility in the global knowledge economy. London, SUNY Press, 2008.

Heyne, P. The Economic Way of Thinking (9th Ed.). London, Prentice Hall, 1999.

Iacobucci, F and Tuohy, C.J. Taking public universities seriously, Volume 2004.Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2005.

Ippolito, R.A. Economics for Lawyers. Carolina, Carolina Academic Press, 2006.

Johnstone, D.B. & Marcucci, P.N. Financing Higher Education Worldwide: Who Pays? Who Should Pay? London, JHU, 2006.

Jones, P &Evans, J. Urban regeneration in the UK. London, SAGE Publications Ltd, 2008.

Knapp, J.C. and Siegel, D.J. The Business of Higher Education: leadership and culture. London, ABC-CLIO, 2009.

Kogan, M. Transforming higher education: a comparative study. London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2000.

Köhler, U and Huber, J. Higher education governance between democratic culture, academic aspirations and market forces, Volume 638.London, Council of Europe, 2006.

Kretovics, M. and Michael, S.O. Financing higher education in a global market. London, Algora Publishing, 2005.

Machin, S. & Vignoles, A. What’s the good of education? the economics of education in the UK. London, Princeton University Press, 2005.

McBurnie, G. & Ziguras, C. Transnational education: issues and trends in offshore higher education. London, Taylor & Francis, 2007.

Office for Budget Responsibility. Economic and Fiscal Outlook. London, the Stationery Office, 2010.

Patil, A.S. & Gray.P.J. Engineering Education Quality Assurance: A Global Perspective. London, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2009.

Schaltegger, S & Bennett, M.D. sustainability accounting and reporting. London, Routledge, 2000.

Scott, P. Higher education reformed. London, Routledge, 2000.

Teixeira, P. Markets in higher education: rhetoric or reality? London, Springer, 2004.

The Stationery Office. HC Paper 48-II House of Commons Innovation, Universities, Science and Skills Committee: Re-skilling for Recovery: After Leitch, Implementing Skills and Training Policies, Volume I. London, the Stationery Office.2007

The Stationery Office. Research Council Support for Knowledge Transfer: Third Report of Session 2005-06. London, the Stationery Office. 2006.

UNESCO. Globalization and the market in higher education: quality, accreditation and qualifications. New York, NESCO, 2002

Webber, P.The UK. London, Nelson thornes, 2006