The symbol at the right is the most used version of the Fleur de Lis, sometimes spelled Fleur de Lys. Its use can be traced back more than 1500 years. During the times of knights, it was often used in heraldry and is still seen on many shields and coats of arms. It was probably first used in France by Clovis, king of the Franks (466–511), (Britannica Online 2008), after which it was a representation of the kings of France. It figures often in church decoration and even on the vestments used for mass. “When Pope Leo III in 800 crowned Charlemagne as emperor, he is reported to have presented him with a blue banner covered (semé) with golden fleurs-de-lis.” (Britannica Online 2008) It became popular in England and even Scotland, because it was very decorative, yet not difficult to reproduce. Even though the common people in France despised it as a symbol of royalty for a while, they soon took ownership of this pretty symbol and carried it around the world. Today it is the symbol on the Quebec flag and the banner of the separatists.

The first mention of the Fleur de Lis, which means Lily Flower, is a story about “a lily given at his baptism to Clovis, king of the Franks (466–511), by the Virgin Mary. (Kipling 1998, 187)The lily was said to have sprung from the tears shed by Eve as she left Eden.” (Britannica Online 2008) It actually represents an Iris, part of the Lily family. “The use for ornamental or symbolic purposes of the stylized flower usually called Fleur de Lis is common to all eras and all civilizations. It is an essentially graphic theme found on Mesopotamian cylinders, Egyptian bas-reliefs, Mycenean potteries, Sassanid textiles, Gaulish coins, Mameluk coins, Indonesian clothes, Japanese emblems and Dogon totems. Most writers agree that it is not necessarily a lily, but disagree on whether it might be an iris, the broom, the lotus or the furze, or whether it represents a trident, an arrowhead, a double axe, or even a dove or a pigeon. The essential point is that it is a very stylized figure, probably a flower, that has been used as an ornament or an emblem by almost all civilizations of the old and new worlds.” (Pastoureau, Michel 2006)

The Fleur de Lis is most recognized as the symbol for French Royalty or as a part of a coat of arms, used in many European countries, including England and Scotland. In France, it became a hated symbol before and during the French Revolution. “Louis Philippe, who called himself the Bourgeois King’ and removed the Fleur-de-Lis from the Palais Royal to show people how nice he was. ‘Louis Philippe afforded France some of the happiest years in her history,’ wrote Andre Maurois, ‘but the French do not live on happiness.’ Once their contempt for Louis Philippe was aroused, they ignored the widespread prosperity of his reign and had a revolution anyway.” (King 1997, 64)

This portrait may be Suzanne de Bourbon in New York. She is shown holding a pearl rosary in a setting backed by a landscape, a common background in the Netherlands. Her ermine-lined gown, decorated with gold beads and embroidery, and the fleur-de-lis-shaped ruby and pearl jewel hanging from her neck show that she is probably a member of the French royal family, and Suzanne de Bourbon is the most likely. Many of the French royalty wore the symbol on their jewellery or clothing since it was restricted to their use before the revolution. It was probably originally blue or purple, and this colour was restricted to royalty for many centuries since it was very expensive to make (Leppert 1996 p. 228).

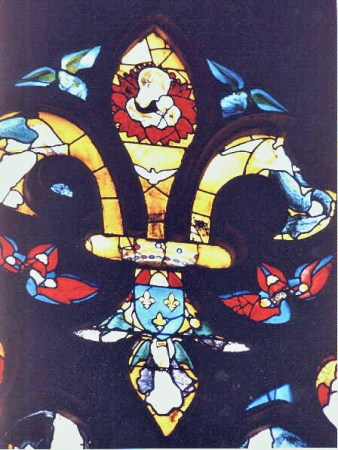

The early Christian Church adopted the Fleur de Lis as a symbol of purity and it was incorporated into church decoration, stained glass windows, and even was used on priests’ vestments. It can still be found around the world in churches, predominantly Catholic, embroidered on table runners, knee cushions, curtains and vestments, and as bookmarks for hymnals and bibles. However, it was possibly a pagan symbol adopted by the early church to entice new membership from the pagan populations. The Fleur de Lis was often seen as a symbol of a kind of partnership between royalty and the church, or as a symbol of the godliness of the monarch. (Kipling 1998, 45)

While the Fleur de Lis was seen on heraldry in many countries, the origin was probably French. The royal families intermarried and new crests and heraldry might have been made in the event of a marriage. These would incorporate the symbols of the two families. So the Fleur de Lis is often found combined with many other symbols. In this manner, it may also have spread from the early Christian church, which eventually became the Roman Catholic Church to other denominations, including the Eastern Orthodox.

This is the Fleur de Lis Chapel, previously Episcopalian, in Upland, California. It is now used as a speciality wedding chapel, and the décor features the Fleurs de Lis very prominently in the interior shot (fig 9) at the right. Since this was previously an Episcopalian Church, this may be an example of the cross adoption of the symbol.

The Fleur de Lis has most recently been recognized as a cultural-socio-political symbol for the Francophone communities in both Quebec and New Orleans. It figures prominently in New Orleans, and, since Katrina, has been considered for adoption of the symbol for the New New Orleans as an innocuous pledge of allegiance to the city and its distinct cultural heritage. The pervasiveness of the Fleur-de-lis in New Orleans is one of the most obvious references to previous French royal ambition in southern Louisiana. For the French monarchy, the Fleur-de-Lis was said to signify perfection, symbolizing light and life. The national French heroine Joan of Arc was supposed to have carried a white banner that showed God blessing the French royal emblem—the Fleur-de-Lis—when she led her troops to victory over the British for Charles VII.

In Louisianna, the debate is on to adopt the Fleur de Lis as the new symbol of New Orleans. (Anderson, Ed 2008) The symbol was brought by the French inhabitants and became very popular as a regional symbol. Right after the hurricane, there was a reported surge in body art in New Orleans, and the Fleur de Lis was extremely popular. (Anderson, Ed 2008) The symbol’s popularity over the ages is partly due to its simplicity, which makes it ideal for skin art. It can be embellished as much or as little as the tattoo artist and the customer desires. It is postulated that the pain of acquiring a tattoo is part of the psychological attraction for survivors of Katrina. All kinds of art picturing the Fleurs de Lis showed up in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, even graffiti on garbage cans.

Another area of socio-political use is in Quebec, Canada. The Quebec provincial flag shows four Fleur de Lis. It has become a symbol of Quebec political power and was seized upon by the Block Quebecois to promote separatism. However, this is not agreeable to all Quebecers, as was shown by two very expensive referendums for Quebec sovereignty which failed. The symbol, itself is actually used by both sides of this issue, with neither of them willing to give it up. It has become a social symbol of the Canadian Francophone community, and being a cultural symbol, those French Canadians who wish to remain Canadian still use it.

Its socio-political meaning is confused and watered down due to this history of everyone claiming it, from the French royal court to the revolutionaries, Napolean and, finally, French Canadians on both sides of the sovereignty question. “There was never a clearer case illustrating the dangers of diffusion of purpose. The Frenchman who sports a fleur-de-lis on his lapel means that he favours the Bourbon restoration, not that he is a monarchist in principle. It is easy enough to make generic declarations. The American who wears a miniature flag in whatever way is, so to speak, singing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ in public.” (Buckley 1997, 75)

People in Quebec are divided upon the issue of whether the province should separate from Canada and become a sovereign country or stay within the federation of provinces. Quebec has not actually signed the Canadian Constitution, because it does not adequately guarantee the province its right to remain somewhat different than other provinces, with laws based upon the French feudal system rather than English Common Law and a distinct linguistic cultural group which needs protection to maintain its culture. Most Canadians, and more than 50% (according to the referendums for separation which failed) believe that Quebec is better off as a province of Canada.

Most residents of Quebec have taken ownership of the Fleur de Lis and they like the Quebec provincial flag. However, for some time, the separatists have thought that the emblem was somehow theirs by right. That would be rather like a citizen of Alaska who favoured a proposed separation from the USA, claiming the big dipper insignia as their own, merely because it is the state flag.

Coats of Arms and Flags

1376

Arms of Edward III

Standard of the French

royal family prior to 1789

and from 1815 to 1830

Scottish royal arms

Fleur-de-lis of Florence

Fleur-de-lis in

the coat of arms

of Pope Paul VI

Fleur-de-lis of Bosnia

National symbol of Bosniaks

Flag of Quebec

Flag of Acadiana

Baden-Powell began awarding a brass badge in the shape of the fleur-de-lis arrowhead to Army scouts whom he had trained while serving in India in 1897. He later issued a copper fleur-de-lis badge to all participants of the experimental camp on Brownsea Island in 1907. (Walker, Johnny 2006)

It was proposed by Jay Wilson in 1939, using the original crest shown in Fig. 13. It is a highly visible symbol of scouting now, displayed on uniforms, publications and equipment used for scouting around the world. (Wikipedia 2008) This is possibly more recognized than either of the French-connected uses in New Orleans and Quebec. Parents everywhere recognize it.

These are actually only a few of the main uses of the Fleur de Lis worldwide. It is simply that the simple, yet graceful, illustration is just very easy to reproduce and easy to modify and embellish to make it personal that keeps it so popular. It has been used on everything from draperies to earrings, and can still be seen in modern wallpapers, finials and upholstery. There is no doubt that the symbol had some strong political overtones and still carries a strong cultural message in many parts of the world. However, its popularity is more than socio-political. It is a unique image recognized from antiquity as a symbol of power and life, purity and grace. This one looks good for a door knocker or some other decoration.

References

Anderson, Ed, 2008, Fleur de Lis May Become Official State Symbol, The Times-Picayune.

Buckley, William F. 1997. The Search for Self-Identification. National Review.

Collins, Michael. 1999. Quebec: Social Union or Separation? Contemporary Review, 116+.

“fleur-de-lis.” Online Art. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition.

“fleur-de-lis.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition.

Fleur de Lis Chapel, 2008. Web.

Kipling, Gordon. 1998. Enter the King: Theatre, Liturgy, and Ritual in the Medieval Civic Triumph. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Leppert, Richard D. 1996. The Cultural Functions of Imagery The Cultural Functions of Imagery. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Otte, Marline. “The Mourning After Languages of Loss and Grief in Post-Katrina New Orleans.”. 828-836. Organization of American Historians, 2007. Academic Search Elite, EBSCOhost.

Pastoureau, Michel (2006) Traité d’Héraldique, “Treatise on Heraldry”, translated by François R. Velde.

Walker, “Johnny” (2006). “The Fleur-de-lis and the Swastika”. Web.