Introduction

Norovirus is a genus of the Calciviridae family and it infects human beings, bovine, swine, feline, murine, and canine species (Hansma et al. 2010). Norovirus causes gastroenteritis and other related diseases in human beings (Jensen 2008). The main symptoms of norovirus include diarrhea, vomiting, low-grade fever, abdominal cramping, and nausea, as table 1shows (Giesecke 2002).

Symptoms of norovirus

Clinical symptoms are manifest between 12 and 72 hours, while the incubation period is between 24 and 48 hours (Giesecke 2002). In America, noroviruses cause about 23 Million infections every year and 90% of all viral gastroenteritis (Ayliffe et al. 2000).

Table 1 Symptoms of Norovirus and their Frequencies

Replication of norovirus is not well understood (LoBue 2008). The common belief is that genomic RNA functions as a funnel of making negative strands, which in sequence works as a funnel of transcription for a complete positive RNA strand for packaging as well as subgenomic RNA for protein manufacture (LoBue 2008).

Modes of transmission

Transmission of norovirus pathogen happens fecal-orally through food and water, directly from person to person, or through environmental contamination (Lundy & Janes 2009). Person to person as well as fomite transmission is prevalent in crowded areas such as evacuated shelters, cruise ships, nursing homes, and hospitals (Jensen 2008; Lundy & Janes 2009). Research shows that after Hurricane Katrina, many evacuated persons who sought shelter at the Reliant Park complex in Houston, Texas acquired norovirus infection. “Approximately 1150, or 5% of the 24, 000 displaced persons obtained refuge at the Reliant Park complex in Houston, Texas, ailed from gastrointestinal illness between September 2, 2005, and September 12, 2005” (Jensen 2008, p.7). Twenty-two stool specimens from the laboratory confirmed the virus. Another study by Lundy and Janes (2009) reveals that on November 20, 2002, cruise ship X reported an increased figure of persons with gastrointestinal symptoms. During a one-week journey from Florida to the Caribbean, 84 (4%) of the 2,318 passengers in cruise ship X had gastrointestinal symptoms. The trend continued in the subsequent cruise ship 2 and health officials suggested that the ship should stop its services for a week so that it could undergo sanitization. Despite the cleaning, 192 (8%) of the 2,456 passengers acquired the infection in the following cruise 3. After a careful survey and analysis of the situation, results indicated that the infection had initially spread from food and afterward from person to person (Lundy & Janes 2009).

Genotypes

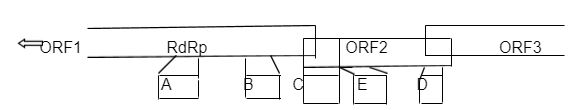

Noroviruses have a cyclic nature and research indicates that there exist five different genotypes of norovirus (GI-GV) (Jensen 2008). These classifications depend on the characteristics of the capsid protein in each group. Genogroup I(G1), G2II, GIII, and GIV infect human beings, apart from the porcine-specific virus in GII, GIII, and GV, which infect bovine and murine hosts, respectively (LoBue ). A study by Gerstman ( 2003) indicates that there is a 51-56% homology amid strains in different genogroups and 69-97% nucleotide homology amid strains in a genogroup. High variables and conserved areas characterize homology amid strains, as seen in figure 1. The link between ORF1 and ORF2 is the most conserved and it holds 86-100% identity in a genogroup (Jensen 2008). ORF1 has more reservations compared to ORF2 and ORF3, where functional motifs in the Pol sequence and cleavage sites are identical (17).

Genotypes that are responsible for noroviruses keep on changing and this poses a huge challenge when it comes to the nomenclature of these genotypes. Hansma et al. (2010) explain that a group of experts seeking to establish a concise way of classifying and describing these genotypes is underway. GII.4 has been the domineering genotype since the 1990s. However, recent research indicates that this cluster is evolving (Green 2007). According to Jensen (2008) there lacks information about traits that make this genotype predominant. Other GII strains cause erratic outbreaks and GI outbreaks to occur rarely. The main factors that cause irregularity in incidences of norovirus are environmental aspects and the formation of new clusters (Lundy & Janes 2009). Winter seasons record the highest incidences since cold weather favors the multiplication of the genotype (Hansma et al. 2010).

The stool of persons with norovirus consists of about 109 RNAs per gram (Hansma et al 2010). Thus, a single gram of stool can infect up to one million people. Caul (1995) in a different study suggests that projectile vomiting, which is atypical of infected persons, has the potential to infect between 0.3 Million and 3 Million people. Marks et al. (2000) further reveal that the risk of acquiring the infection is inversely proportional to the risk of being infected. If a country has 300, 000 infected persons in a population of 3 Million, then the possibility of getting the infection is 1/10 and conversely, the population at risk is 10%.

According to Atmar et al. (2008), patients may continue to spread the virus for up to four weeks after recovery. However, this duration is longer in children (Rocks et al., 2002). Another study by Lee et al. (2007) focused on people from different age groups. This study discovered that the stool of old people, as well as persons who had suffered from diarrhea for an extensive period, contained a high number of norovirus infections.

In the past years, there has been little development in terms of surveillance of the disease due to the lack of molecular technology to capture the specific strains and norovirus causal agents (Riley 2004). Currently, there exist advanced methods of surveillance and the use of RT-PCR reagents to capture norovirus activity. These advancements are likely to change epidemiological trends in the future.

Preventive measures

Measures to prevent norovirus should consider causal factors of the virus. As mentioned earlier, the main factors in which the virus spread include person-person and transmission through food or water, actions like handling water and food hygienically disinfection, hand washing, and isolating sick persons. Presently, researchers are still working to see if they can establish a vaccine for the norovirus infection. The biggest problem in their course is that GII.4, which is the main strain that causes the virus, exists in different strains. Lopman et al. (2006) presented a model to test whether different causes of norovirus have resemblance about their molecular formations and many researchers have adopted this model in their course. If research concludes that the virus has a common source, it would be very easy to come up with preventive measures.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the number of infections caused by noroviruses has increased steadily over the years. Besides, identifying the exact microorganisms responsible for the spread of this illness has been an intricate issue. While researchers recognized GII.4 as the leading genotype responsible for norovirus infections, during the early years of this century, efforts to find the underlying factors about why GII.4 dominates other genotypes when it comes to spreading the norovirus infection have been fruitless.

References

Atmar, RL, Opekun, AR, Gilger, MA & Crawford, AC 2008, ‘Norwalk virus shedding after experimental human infection’, Emerging Infectious Diseases, vol. 14, pp.1553-1557.

Ayliffe, GAJ, Fraise, AP, Geddes AM, & Mitchell, K 2000, Control of hospital infection: a practical handbook, 4th Ed, Oxford University Press, New York.

Caul, E 1995, ‘Hyperemesis hiemis-a sick hazard’, Journal of Hospital Infections, vol. 30, pp.498-502.

Gerstman, B 2003, Epidemiology kept simple: an introduction to classic and modern epidemiology, Wiley Press, New York.

Giesecke, J 2002, Modern infectious disease epidemiology, 2nd Ed, Hodder Arnold, New York.

Hansma, GS, Jiang, X, & Green, K 2010, Caliciviruses: molecular and cellular virology, Horizon Scientific Press, New York.

Jensen, N 2009, Public health and environmental infrastructure implications of hurricanes Katrina and Rita, Diane Publishing, London.

Lee, N, Chan, M & Wong, B 2007, ‘Fecal-viral concentration and diarrhea in norovirus gastroenteritis’, Emerging Infectious Diseases, vol. 13, pp. 1399-1401.

Lobue, AD 2008, Norovirus immunobiology and vaccine design, Proquest, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Lopman, BA, Gallimore, C, Gray, JJ & Vipond, IB 2006, ‘Linking health-care-associated norovirus outbreaks: a molecular epidemiologic method for investigating transmission’, BMC Infectious Diseases, vol.6, p. 108.

Lundy, KS & Janes S 2009, Community health nursing: caring for the public’s health, Jones & Bartlett Learning, London.

Marks, PJ, Vipond, L & Carlisle, D 2000, ‘Evidence for airborne transmission of Norwalk-like virus in a hotel restaurant’, Epidemiology Infections, vol.124, pp. 481-487.

Riley, L W 2004, Molecular epidemiology of infectious diseases: principles and practices, ASM Press, London.

Rocks, B, Vennema, H & Van, D 2002, ‘Natural history of human calicivirus infection: a prospective cohort study’, Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol.35, pp.246-253.

Vinje, J, Hamidjaja, RA & Sobsey, MD 2004, ‘Developmental and application of a capsid VPI (region D) based reverse transcription PCR assay for genotyping of group I and II noroviruses’, Journal of Virology Methods, vol. 116, pp. 109-117.