Introduction

In Australia today, there are quite a number of social issues that play critical roles in determining the health of the population. These social determinants of health are varied and they include factors like the nature of the health system itself and people’s working conditions. These conditions, other than being responsible for health inequities, may also lead to the onset of other infections in an individual’s health. This essay will explore the epidemiology of cancer as a social determinant of health. In addition, theoretical and sociological perspectives will be employed in discussing the social impacts of this terminal infection.

Epidemiological statistics of cancer

As a terminal infection, all forms of cancer are known to affect body cells. In the case of a cancer attack, the cells of the body uncontrollably reproduce themselves and sometimes end up growing into lumps (Lewis, 2003). The latter is referred to as a tumor. It can be made up of cells affected with cancer leading to the formation of a malignant tumor. The other type of tumor is called a benign tumor (Lachmann et al., 2011). Unlike the malignant tumor that spreads to the other parts of the body, the benign tumor affects only the area it first developed (Khoo, 2003). Malignant tumors may grow in other parts of the body after spreading to form secondary cancer also known as metastasis (Lewis, 2003). Skin cancers, bowel cancer as well as prostate cancer are just but a few examples of cancer that have been commonly diagnosed among patients (Tyrrell, 1999). Although cancer has varied causes, common triggers of this illness include bacterial infections, exposure to ultraviolet rays from the sun as well as a weak immune system (Lachmann et al., 2011).

The prevalence of cancer has been of great concern to both the population and health authorities in Australia. The social, economic, and personal costs associated with the diagnosis and treatment of this disease is rather high. In 2005, over one hundred thousand new cases of cancer were diagnosed in Australia. According to the research findings, newly diagnosed cases in males were estimated at 56,158 (Khoo, 2003). This figure has been projected to be growing each year by at least three thousand.

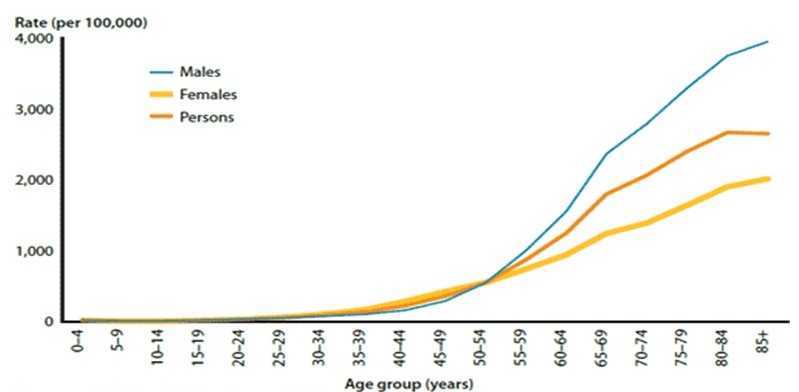

In terms of prevalence, both the young and old generation is affected. The prevalence rate is higher among males aged 55 years and above and worsening for women at age of 84 (Williams & Bramwell, 2003). Individuals who are at risk vary depending on the type of cancer. Some types of cancers can be found in both young and old people. For instance, skin cancer affects all age groups. However, the risk is greater in older people, those who have been diagnosed with melanoma or depending on the medical history of their families, those who are immune-suppressed, light-skinned individuals, and those who are exposed to ultraviolet radiations (UVR). Children and outdoor workers are examples of risk groups for skin cancer.

On the same note, the absolute risk of developing breast cancer is lower in young women than in old women. The older an individual grows, the higher the chances of developing breast cancer (Tyrrell, 1999). Another risk factor is the inheritance of particular genes by the women from their families. The gene, BRCA1 or BRCA2, is an inherited mutation with an assurance of cancer to over 46% of women if they live to up to 80 years (Lachmann et al., 2011). Besides, women who take alcohol are more likely to get breast cancer. These and many others indicate that each type of breast cancer has a commonly affected risk group.

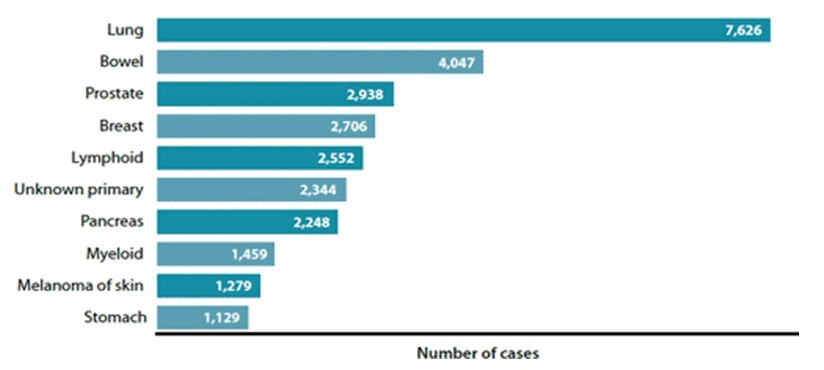

Among males, prostate cancer takes the lead with 16,439 new cases followed by colorectal cancer. Other types of cancer affecting men include lymphoma, lung, and melanoma of the skin. Generally, women are more affected than men. In 2005, the number of females diagnosed with new cases of cancer stood at 44,356 with breast cancer being the topmost threat (Williams & Bramwell, 2003). It is important to note that other than sex-specific cancers; other common cancers like that affecting cancer, melanoma of the skin, colorectal cancer, and so on are the same for both males and females. In all these types of cancers, there is less prevalence among females than males with colorectal cancer being 1.4 times higher in females than males (Jalland, 2006).

Other types of cancer in males rating higher than women are mesothelioma with a male to female ratio of 5.2, hypopharyngeal 5.5, Kaposi sarcoma 7.5, and laryngeal cancer 9.3 (Lachmann et al., 2011). On the other hand, females too have some cancers rating higher than males and these include thyroid cancer 3.0, retroperitoneum and peritoneum cancers 4.0 and breast cancer 111.0.

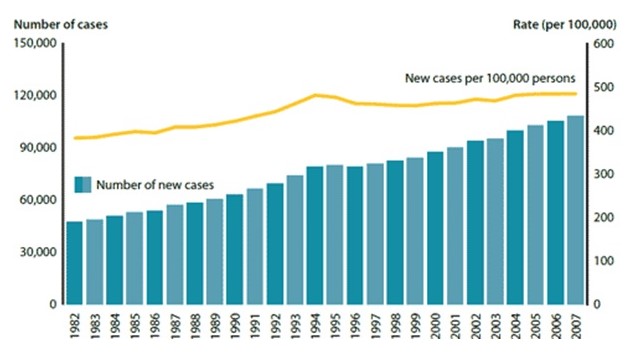

In 2007, research study findings in Australia showed that the most common cancers were prostrate, bowel, melanoma of the skin, lung and breast cancer. The risk was higher among old females than the males and the number of new incidences had risen in 2007 to 108,368 from the earlier figure of 47,350 in 1982 (Tyrrell, 1999).

The health care system dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of cancer is both in private and government institutions in Australia. Medicare, the government health system works together with the private healthcare sector to manage the causes, prevalence and treatment of cancer. Over 700,000 diagnoses and about 10 % of some separations that were cancer related were done and experienced respectively in the 2004-2005 (Lachmann et al., 2011). From 2001-2005, hospital separations that are cancer related increased by 4.5%.Other similar separations included prostrate cancer 15.1% and colorectal cancer 2.9%. Since cancer treatment is costly, the government and the public are forced to bear the full weight of treatment cost. Other than taxes and insurances which cover about 1.5%, the government has to spend 8.8% on health system (Williams & Bramwell, 2003). Other than this, an individual needs to plan for that treatment, buy drugs and pay for treatment sessions. Health care system therefore takes about 67% of government expenditure (Anon. 2011).

It is important to note that cancer, according to reports given by AIHW and AACR, is a major disease in Australia. In cancer, abnormal growth of cells in the body spread uncontrollably to other parts of the body (Bourke, 1983). Other cancer related diseases which display threatening abnormal cell growth throughout the body include Hodgkin’s disease and the related one that affects the lymph known as non-Hodgkin’s disease, sarcoma of the bones, leukaemia, and malignant tumors. Reports given by Australian national agency for health and welfare statistics and information (AIHW) in 2006 indicated that the leading contributor of disease burden among Australians was cancer by 19%. In fact, of the total disease burden in Australia, lung, colorectal and cancer of the breast were notably diagnosed among patients (Tyrrell, 1999).

Furthermore, reports from AIHW and AACR have indicated that prevalence data of cancer in Australia is much higher than incidence data. The number of people living in private dwellings and suffering from cancer at a point in time is higher than the overall population diagnosed with cancer in a specific period (Williams & Bramwell, 2003). In 2004-2005, an estimated 390,000 Australians were screened for cancer and of the total population, 14% had an uncertain nature of benign neoplasm while 87% were diagnosed of malignant neoplasm (Khoo, 2003). Besides, the reports indicated that there was a significant increase in the population with malignant skin cancer between years 2004-2005 with the figures moving from 94,300-147,900 (Anon. 2011).

In an analysis done by researchers to investigate the correlation between cancer and age, it was observed that until the age of 30, the rates of cancer incidents were the same for both the males and the females. The differences in incident rates in women grew higher than men from ages 30-53 and at 41 it peaked to 1.8 times higher than men. It is important to note that in the life span of males, several common cancers are likely to affect them. At infancy, neuroblastoma is likely to affect them and also lymphoid leukaemia which is likely to affect the ages 1-15. Additionally, melanoma of the skin and the testicular cancer is likely to affect them between the ages of 16-29 with the former advancing up to the age of 51. At 51 onwards and for the remaining part of their lives, they stand at a risk of developing prostrate cancer. In females, cancer during infancy appears like that of the males (Williams & Bramwell, 2003). However, melanoma of the skin affects them at the ages of 17-33 and the years that ensue from 34-75, they are likely to develop breast cancer and for the remaining years suffer from colorectal cancer. The incident rate of cancer in males is higher than females at the age of 55 and above.

Moreover, the impact of cancer in the Australian health system is significant and accounts for 19% of the total burden of disease. Hospital utilization is one of the aspects of the burden of cancer disease. Hospital separations from cancer in the 2006-2007 financial year in Australia was over 775,000 with almost half of it being due to chemotherapy sessions (Bourke, 1983).

Mortality

pancreatic, colorectal, breast, prostrate and the being lung cancer are known to be acute forms of cancer that have raised the mortality rate in Australia. Even though there has been screening programs for cancer that has brought reduction in the death rates and improved chances for survival, death rate due to cancer has been above 800 people yearly since 2005.These statistics together with those of deaths of up to above 39,000 deaths since 2005 in Australia shows the impact this disease has on the population and the health system. It is a major source of morbidity and mortality with over 80,000 new cancer cases and over 33000 deaths (Rodriguez-Biga, 2010).

Between 2002 and 2004, the main underlying cause of death in Australia was cancer infection with up to twenty eight percent of deaths recorded each year under survey (Bourke, 1983). Among the children of ages 1-14, cancer is uncommon. Nonetheless, leukemia and brain cancer are the leading causes of death with up to 18%. Besides, studies indicate that lymphoid, colorectal, prostrate and lung cancer are the underlying causes of mortality among men with 10%, 13% and 22% risk levels respectively (Anon. 2011). On the other hand, cancer of the lymphoid and related tissues, colorectal cancer, lung and breast cancers are leading causes of deaths among females represented by 10%, 12%, 15% and 16% respectively (Anon. 2011).

Furthermore, reports from AIHW points out that deaths due to the common skin cancers in Australia is low and only happens when an individual fails to get an early treatment. Among the indigenous Australians, 17% of all deaths are caused by cancer (Bourke, 1983; Challenger, 1994). Reports from the AIHW indicate that the leading cause of death among this group is the lung cancer, cancer of the digestive organs as well as other smoking-related cancers. In terms of hospitalization, it is lower among the indigenous Australians compared to the other Australians represented by 1070 and 1344 respectively (Williams & Bramwell, 2003).

In 2005, 22,017 males died of cancer with lung, prostrate, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers as well as cancer of unknown primary site representing 58% of all cancer deaths (Lewis, 2003). Based on the data collected in 2005, the risk of dying due to cancer among the males before the age of 75 and 85 was 1 in 8 and 1 in 4 respectively (Rodriguez-Biga, 2010). An extreme and unique risk of death among the males was from lung cancer with a chance of 1 to 31 before the age of 75 and 1- 14 chances before the age of 85 (Jalland, 2006). On the other hand, 17080 females died from breast, lung and colorectal cancers in the same year. Chances of dying before the age of 75 among them stood at 1in11 and 1 in 6 before the age of 85 (Jalland, 2006).

According to AIHW reports of 2007, the mortality rate among the Australians due to cancer was 39,884 represented by 17,322 females and 22,562 males (Bourke, 1983). These figures could be interpreted to mean that every day, an average of 109 Australians died of cancer (Anon. 2011). However, it is important to observe that unlike in the years 2004-05 in which cancer was the leading cause of death, cancer was the second cause of death in 2007. Additionally, the risk of dying from cancer among the females was 1 in 12 and for males 1 in 8 before the age of 75 (Jalland, 2006). At the age of 85, the risk of dying in males was at 1 1n 4 and in females stood at 1 in 6 (Anon. 2011). The most common causes of death due to cancer were lymphoid cancer, breast cancer, prostrate cancer, bowel cancer and lung cancer.

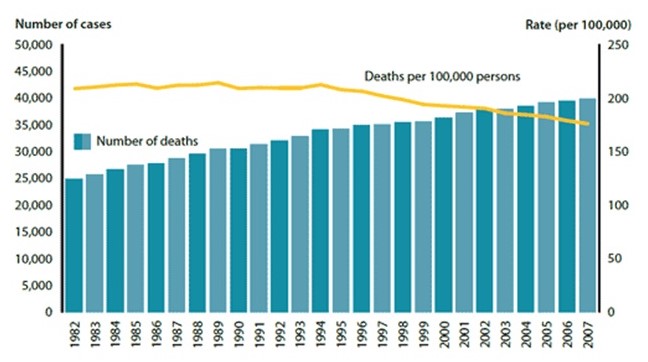

It is important to note that the number of mortality had initially increased from 24,992 deaths in 1982 to 39,884 in 2007(Rodriguez-Biga, 2010). According to statistics, the increase represented 60% of all deaths due to cancer. However, when combined, the age standardized death rate for all cancers in Australia fell to 176 deaths per 100,000 Australians in 2007 from 209 deaths per the same people in 1982 (Anon. 2011). These figures represent a fall of 16% of mortality rate among the different ages.

Sociological perspectives

The way individuals view issues happening in the social world depends on the different perspectives provided by the theories in sociology. A set of designed principles and interrelated propositions that can provide perspectives on a particular phenomenon and give answers to questions helps individuals to understand issues affecting the society they are living in (Lupton & Najman, 1995). Further, these set principles and interrelated propositions forming a theory helps individuals to sociologically predict the world they are living in. Individuals explain the phenomenon happening around them in using three major theoretical perspectives. It is important to understand that it is these three theoretical perspectives that designs answers to particular questions in life about causes and provides perspectives of possible solutions. The perspectives include the symbolic interactionist perspective, the conflict perspective and the structural functionalist perspective (Lupton & Najman, 1995).

According to Karl Marx theory, structural functionalist perspective works in creating a social balance, a state of equilibrium, harmony and interconnects various aspects of the society. For instance, in any given society, different social institutions such as religion, family, politics and economics plays a key role in transmitting in the society issue4s like culture, knowledge and skills to various individuals. Additionally, this perspective focuses on how one social institution influences individuals or how they influence each other with an emphasis on interconnectedness of a society.

On matters relating to health issues like cancer and its epidemiology, the terms functional and dysfunctional are used with the latter referring to issues disrupting the stability of the society (Lupton & Najman, 1995). Health issues and their effects in terms of injury and mortality is a dysfunctional aspect of any given society. Functional aspects are important as they contribute to social stability. In this sense too, health injuries and mortality can be functional aspects that contributes to increased social cohesion and creation of awareness (Lancaster, 1990). Furthermore, Marx uses the conflicting perspective to elaborate more on economic inequalities and competing values and interest in the society. Individuals who are in dire afflictions may feel a sense of meaninglessness, alienation or powerlessness due to their illnesses or poor conditions. This is particularly visible among patients who have been diagnosed with cancer at a late stage of the disease and are unable to get full treatment.

According to functionalisic ontology of EmileDurkheim, his theory has basis on the philosophy of other social philosophers such as Comte, Rousseau and Voltaire. In his theory influenced by biophysics, he argues that biological necessities are determined by social configurations (Lupton & Najman, 1995). Again, from this perspective lie the important aspects of modern public health which are social cohesion and social exclusion. Issues like poverty and illness deny individuals the chance to get social acceptance and therefore they end up being excluded. According to Durkheim, there is need for governments to develop social policies whose goals will be to ensure survival to everyone by availing necessary resources in this competitive society.

In relating the theories of Karl Marx and Emile Durkheim on social pathology and social disorganization using structural-functionalist perspective, it is important to apply the theories of social problems. One important aspect of these problems in the society according to the social pathology model is that they come as a result of some sickness. In this case, when individuals in the society develop cancerous infection, the normal function of their systems, organs and cell gets disrupted and using the elements of culture and structure as well as the functional aspect, this makes the whole society ill. Socially an ill society has its institutions affected and so cannot function effectively (Lancaster, 1990). Cancer and the rising mortality rates in Australia play an important role in affecting social cohesion through hospitalizations. This also makes the sick individuals to be alienated (Lancaster, 1990). Additionally, the sickly and their families or friends feel a sense of helplessness, powerlessness and hopelessness against the illness. Such disturbing feelings of insecure health status in the society negatively affect family institutions alongside creating inadequacies in the Australian political, educational and economic institutions.

Conclusions

Cancer is a major healthcare concern in Australia. The disease burden caused by this terminal illness is increasing each year with more deaths being recorded among the elderly population. While the prevalence and mortality statistics are alarming, early detection remains to be the most effective way to manage all forms of cancer.

To draw a conclusion using Karl Marx and Emile Durkheim theories, the concept of social quality should be integrated in public health. The government and institutions of health should reformulate ethics afresh by ensuring that the gap that is increasing between medical ethics and medical expertise, ability and desirability are checked. By so doing, the modern public health problems affecting the society institutions will be addressed appropriately. Moreover, issues concerning social determinants of health in relation to cancer needs to be tackled through biological hygiene of domestic and urban spaces. This can be achieved through natural scientific epidemiology and following this perspective, management and control of cancer can indeed be a broad possibility.

References

Anon. 2011. Clinical Epidemiology; New Clinical Epidemiology Study Findings Recently Were Published by Researchers at University of South Australia. Web.

Bourke, J. G. 1983. The Epidemiology of cancer. Sydney: The Charles Press Publishers.

Challenger, F. D.1994. Durkheim through the lens of Aristotle: Durkheimian, Postmodernist, and communitarian Responses to the Enlightenment. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield publishers Inc.

Khoo, S. 2003. The transformation of Australia’s population: 1970-2030. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press Ltd.

Lachmann, P. et al. 2011. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK/Authors’ reply. Web.

Lancaster, O. H. 1990. Expectations of life: a study in the demography, statistics, and history of world Mortality.New York: Springer.

Lewis, M. J. 2003. The People’s Health: Public health in Australia, 1950 to the present. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Inc.

Jalland, P. 2006. Changing ways of death in twentieth-century Australia: war, medicine, and the funeral business. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press Ltd.

Lupton, M. G. & Najman, M. J. 1995. Sociology of health and illness: Australian readings. South Melbourne: Superskill Graphics Pte Ltd.

Rodriguez-Biga, A. M. 2010. Hereditary Colorectal Cancer. Hague: Springer Science + Business media LLC.

Tyrrell, B. R. 1999. Deadly enemies: tobacco and its opponents in Australia. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press Ltd.

Williams, C. J. H. & Bramwell, V. 2003. Evidence-based oncology. Tavistock Square: BMJ Publishing Group.