Introduction

One of the reasons why the documentary Food, Inc. can indeed be referred to as being thoroughly convincing is that, while working on it, its makers proved themselves thoroughly capable of taking a practice advantage of the rhetorical devices of an appeal to ethos, logos, and pathos. They also succeeded in ensuring smooth transitions between the deployed lines of rhetorical argumentation. In my paper, I will explore the validity of this suggestion at length, while specifying the qualitative aspects of how the documentary goes about trying to win the viewers’ support for the promoted cause, and outlying what can be considered the deficiencies of the used line of reasoning.

Analytical part

The first idea that is being promoted throughout the documentary’s entirety is that the American food-industry deliberately misleads consumers, as to what is the actual content of food-items, bought in supermarkets, and that this situation can no longer be considered tolerable. This is because, as the documentary implies, denying people their right to know what they consume is the blatant violation of their constitutionally guaranteed rights and freedoms. Food, Inc. also argues that there are several clearly immoral aspects to the earlier described situation, as the process of the food industry’s continual consolidation results in establishing ever more preconditions for the unfair treatment of domestic animals.

In the documentary, there are many instances of its makers providing viewers with the factual information, as to the discussed subject matter, which is supposed to convince the latter in the full legitimacy of people’s concern about how the food-industry treats them. These instances are best discussed within the conceptual framework of the ‘appeal to logos’ rhetorical technique, which is being commonly used as the mean of ensuring the deployed argumentation’s perceptual ‘non-biasness.’ As Oring noted: “Logos is concerned with the argument of the narratives and their attendant commentaries” (130). For example, while elaborating upon the fact that the ingredient of corn can be found in just about any food-product and that there is something utterly wrong about it, the documentary’s narrator presents viewers with the visualized data, as to the mentioned phenomena’s practical implications.

In its turn, this was meant to prompt viewers to think that there is indeed nothing personal about how the documentary discusses the issue in question.

To increase the extent of the argumentation’s discursive plausibility even further, the featured guest Michael Pollan points out to the fact that there is a rationale-based reason for American farmers to consider feeding their cows with corn: “Cows are no designed by evolution to eat corn. They are designed to eat grass. The only reason we feed them corn is that corn is cheap” (00.22.51). This, again, is supposed to cause viewers to think that how the documentary describes the current state of affairs in the country’s food industry is thoroughly legitimate because the very laws of economics naturally predetermined it.

While knowing perfectly well that the viewers’ exposure to the ‘appeal to logos’ rhetorical technique alone can hardly result in causing them to adopt the promoted point of view on the issue, documentary creators also relied heavily on appealing to the audience members’ emotional sensibilities – hence, proving their awareness of what the so-called ‘appeal to pathos’ rhetorical device stands for. According to Micheli: “In a rhetorical situation, the audience ultimately has to pass judgment on a given case. Through skillful use of pathos (appeal to emotions), the orator modifies the audience’s disposition to pass judgment so that it favors the cause which he wants to see prevail” (6). The most easily recognizable instance of the ‘appeal to pathos’ device being used in the documentary is the scene that exposes viewers to the image of a dying chicken.

While viewers observe this chicken’s convulsions, the off-screen narrator tells them that the reason behind the high rate of mortality among chickens is that they are excessively fed to make them gain weight as soon as possible. As a result, many of them grow fat to the extent that their legs can no longer endure their weight – hence, causing the poor creatures a great deal of suffering. It is needless to mention, of course, that after having been exposed to this emotionally disturbing image, viewers would be much more likely to recognize the validity of the documentary’s overall line of reasoning.

There is another example of the successful deployment of a pathos-fueled rhetorical argumentation in the documentary, concerned with the scene in which Barbara Kowalcyk begins to cry while talking about the story of her son Kevin’s death, due to food-poisoning: “He (Kevin) begged for water. That was all he would talk about – water” (00.31.09). By having included the earlier mentioned scene in the documentary, its makers strived to convince viewers that, contrary to what the majority of people tend to think, how the country’s food-industry operates is associated with several bright and present dangers to these people’s well-being. It needs to be said that the filmmakers did succeed in it rather marvelously, as the very context of emotionally disturbed parents talking about their children’s suffering, denies even a slight possibility for them to sound insincere. This, of course, provides emotionally sensitive viewers with an additional reason to subscribe to the documentary’s argumentative point.

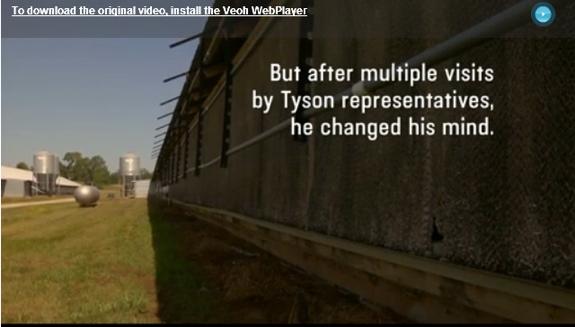

Throughout the film’s entirety, there are also many examples of its creators taking advantage of the ‘appeal to ethos’ rhetorical technique, when audience members are being prompted to assume certain things about the involved stakeholders – hence, providing viewers with additional incentives to believe that the line of the documentary’s argumentative reasoning represents a universally recognizable truth-value (Connors 285). The validity of this statement can be well illustrated in regards to the film scene that features the following textual sequence:

Documentary creators did not have any hard evidence, as to the fact that the representatives of Tyson Corporation were applying any pressure on Vince, to make him decline the journalists’ request to film inside of his chicken-farm. Yet, as the above-screenshots imply, this was the actual case – by encouraging viewers to consider that there was indeed a connection between the visits of Tyson’s representatives and the Vince’s sudden ‘change of heart,’ filmmakers succeeded in ensuring the soundness of their subtle allegation of Tyson Corporation being involved in semi-criminal scheming against farmers.

Another example of how the ‘appeal to ethos’ technique is being used in the documentary, is the scene in which one of the interviewed farmers talks about the actual realities of the American justice system’s functioning: “Lady Justice has the scales. The one who puts more cash on the scales… wins” (01.15.04). It is understood, of course, that this statement was meant to appeal to the viewers’ deep-seated mistrust towards the country’s state-institutions, as such that are being affected by corruption. This is because people tend to assume that the statements, which correlate with what happened to be the essence of their unconscious anxieties, are true by definition (Lamb 109).

Nevertheless, even though that there can be only a few doubts, as to the documentary’s rhetorical effectiveness, it would be entirely inappropriate to suggest that there are no discursive drawbacks to how film creators argue their case. For example, one of the main ideas, promoted by the film, is that there are objective prerequisites for the current dynamics in America’s food-market to be what they are – specifically, the fact that, as time goes on, the gap between the poor and the rich in this country continues to widen. Moreover, the number of impoverished people keeps on growing rather drastically, which in turn implies that the food-producers specifically can provide consumers with particularly cheap food-items, which should be seen as the foremost precondition for them to remain commercially competitive: “To eat well in this country costs money… and some people don’t have it” (01.27.32). Therefore, there is very little sense in the documentary’s concluding remark: “People have to start demanding good wholesome food” (1.29.19). Those that have the means do not need to ‘demand’ organic food – they just buy it. Alternatively, regardless of how strongly poor people would be willing to ‘demand’ healthy foods, they will still not going to get any, simply because they cannot afford it – pure and simple. Therefore, I cannot say that the film did convince me to start ‘thinking organic.’

Conclusion

I believe that the earlier provided line of argumentation, regarding the documentary’s rhetorical subtleties, entirely correlates with the paper’s initial thesis.

Works Cited

Connors, Robert. “The Differences between Speech and Writing: Ethos, Pathos, and Logos.” College Composition and Communication 30.3 (1979): 285-290. Print.

Freund47.“Food, Inc.” Online video clip. Veoh. 2012. Web.

Lamb, Brenda. “Rhetoric.” English Journal 87.1(1998): 108-109. Print.

Micheli, Raphaël. “Emotions as Objects of Argumentative Constructions”. Argumentation 24. 1 (2010): 1-17. Print.

Oring, Elliott. “Legendry and the Rhetoric of Truth.” Journal of American Folklore 121.480 (2008): 127-166. Print.