Introduction

The UK construction industry is one of the core economic sectors, and the output of the industry is a component of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In 2014, the construction sector contributed £103 billion, or about 6.5% of the GDP. The sector employs 2.1 million or 6.2% of the total workforce (Haynes 2017). Forecasts indicate that output will rise by 1.3% in 2017, by 1.8% in 2018, and further increase by 2.3% in 2019. The sector saw a contraction in the aftermath of the economic recession of 2007 and remained under recession until 2014, when fractional growth started (ONS 2017). The sector is organised into different subsectors. These subsectors are public housing new, infrastructure new, public non-housing new, private industrial new, private commercial new, public housing repair and maintenance, private housing repair and maintenance, infrastructure repair and maintenance, and public and private non-housing repair and maintenance. Informally, the sector is organised into private and public housing; office, commercial, and retail; and infrastructure work (Rhodes 2017).

Costs are an important factor in the construction sector, and these costs include labour, materials, equipment, other input costs plus taxes, and contractor margins. In the past decade, these input costs have increased by 10.3% at the lower end, while contractor margins have shrunk. With rising costs, reduced margins and reluctance by banks to lend funds, contractors are under pressure to deliver quality projects on schedule (Haynes 2017). Key Performance Indicators (KPI) with benchmarked figures are used to evaluate the performance of a construction firm (Glenigan 2017).

The industry comprises a large number of small and private contractors and construction firms, and a few large firms that take up large local and international projects. Competitive advantage comes from the ability to manage and deploy resources effectively, manage the supply chain for the highest efficiency, reduce costs and wastage, and complete projects on time (Construction Products Association 2017). This proposal examines the structure of the construction sector, details subsectors and their cost structures, and evaluates the competitive strategy that large firms use to survive and grow.

Literature review and background

The UK construction sector is complex, as it covers many areas and activities. Small contractors take up work that may cost a few hundred pounds, while a large contractor such as Balfor Beatty takes up projects that are worth billions of pounds. Another complication is that larger contractors usually contract the work to smaller contractors who employ a few workers. These smaller contractors become a part of the large project. The cost structures are also different, since a small firm would have low fixed costs, while a large firm would have high fixed and variable costs. Costs also depend on the project location, as projects in remote areas have higher transportation costs (Haynes 2017). This section briefly reviews the literature on the construction sector and the costs and competitive strategy used in it.

Construction sector structure

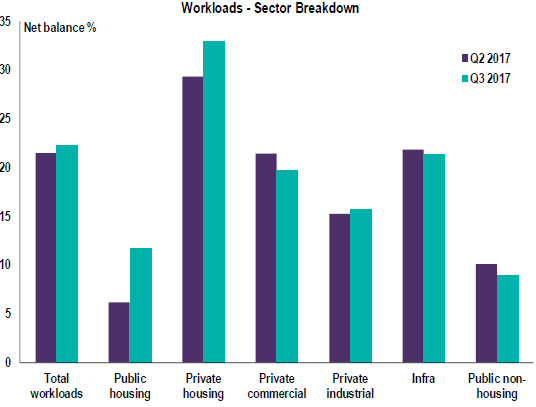

As indicated in the introduction, the construction sector is composed of five subsectors. The growth dynamics and workload are different for each sector. Workload refers to the amount of capacity utilised by a sector versus its full capacity. Fig. 1 illustrates growth in these subsectors and the workload.

As seen in Fig. 1, private housing has the largest share and capacity utilisation of 33%, followed by infrastructure at 22% and private commercial at 18%. These figures indicate that the subsectors operate at below their rated workload. With the industry still under recession, the figure shows that construction has yet to make full recovery. In almost all areas, workload for Q3 2017 is less than that of Q2 2017. Total workload is low at 22%. Large infrastructure projects such as railways can help the industry to recover. Government spending has declined in the areas of public non-housing projects. Several factors such as uncertainty over Brexit have reduced investment. The gap identified is that it is not clear what the structures of these subsectors are, whether they are interrelated, to what extent they are fragmented and specialised, and what effect they have on competition and costs.

Construction costs

Construction costs have several components such as the cost of land (which can make up almost 40-60% of the building costs), material and labour costs, and taxes. Costs also depend on factors such as the project location, type of structure, intended use, funding and interest costs, and safety features; these factors can increase construction costs by 100%. Infrastructure project costs are different, as the land costs, size of the project, funding options, and procurement strategy are different; it is difficult to generalise construction costs. Databases are available that provide indicative costs. Therefore the cost structures for each of the six subsectors are different. The construction costs of a public railroad would be different from a private retail park, since the amenities offered and luxury features provided are different. With the government mandate of energy efficient buildings, the costs of constructing green buildings have increased. Methods of procurement also define costs (McGuckin 2016).

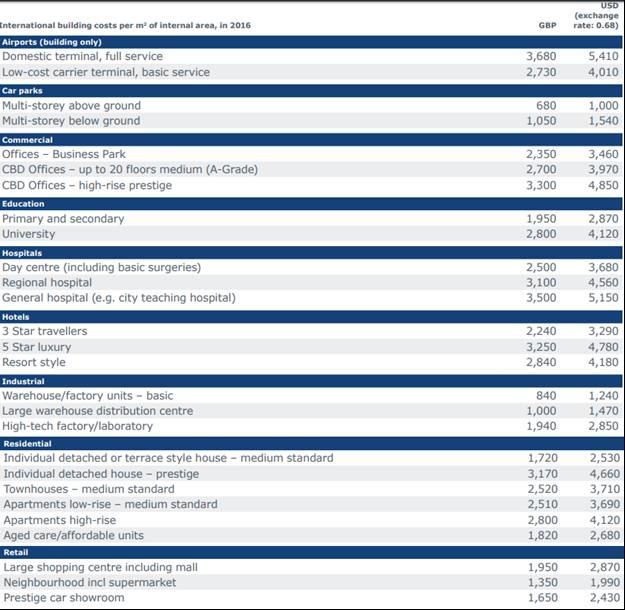

Cunningham (2013) discusses general factors that influence costs. Some of these are time and schedule, architect and designer costs, geometry and building envelope, plan shape, size, wall to floor ratio, free space, number of storeys, total height, and clusters of buildings. Economies of scale can be applied when constructing buildings for a large housing complex where the same design and layout is used for all properties. Other factors are materials used (since exotic materials such as Italian marble can add 20% to costs), sustainability features required, nature and physical condition of the site, location, accessibility, resources available, type of procurement – such as traditional, design and build, management procurement, or payment and tendering agreements – regulation constraints, and market conditions. Delays in supply chains, unexpected complexity and technical challenges, and requested changes can increase the costs by more than 100%. Commercial spaces such as offices and retail centres are completed at a much faster rate since the project owner needs to make time-bound deliveries (Arcadis 2017). Fig. 2 presents costs per square meter for different types of buildings in London.

As seen in Fig. 2, construction costs vary from 680 GBP/square meter for a car park to 3680 GBP for a full-service domestic terminal. Indicative costs for other types of buildings are also given, including commercial space, schools and universities, hospitals, hotels, industrial, residential, and retail. Based on the market price of materials, actual costs may vary. Margins or profits for contractors and construction firms are crucial for their survival. Construction costs indicated in Fig 2.2 do not reflect the margins. Intense competition, increasing material and transportation costs, delays, and risks all squeeze margins. On average, margins in the UK stand at 4% of the costs. If costs increase at any point during a project, the contractor has to bear the costs and suffer a loss (Arcadis 2017). The gap noticed in this section is that while general and indicative costs are known, the exact costs for different types of projects, as well as the input costs, margins, and the effect of competition on these costs is not clear.

Competitive strategy and advantage

There are unique factors and resources that a company can deploy to obtain competitive advantage. Firms can be cost leaders or quality leaders, and a resource-based view of organisations helps to understand the competitive advantage of construction firms. Often a contracting firm and the contractor have a confrontationist attitude, with each party trying to negotiate better terms at the cost of the other. Obvious factors that provide a competitive advantage are access to lower, steady prices of raw materials and labour, ability to avoid delays and adhere to schedule, and the ability to obtain better rates. A construction firm has very little control over these resources. Large firms often take up international projects where risks and uncertainties are higher. Many firms own or lease expensive equipment, and if these machines remain idle, then costs increase (Zhigang, Fei, Heng, & Martin et al. 2013). Ogunbiyi, Goulding & Oladapo et al. (2014) describe new techniques that large construction firms are using to increase performance and gain a competitive advantage. Some of these techniques are Building Information Systems (BIM), lean construction, and the Earned Value Method (EVM). The gap that needs to be examined includes the factors that provide competitive advantage, the manner in which construction firms obtain and deploy them, and the competitive strategy they use.

Motivation statement and problem identification

The literature review section showed that the construction sector sees intense competition among all subsectors. With a shrinking market and reduced margins and costs, it is essential to understand the dynamics and interrelation of these subsectors, assess their structure, and evaluate the impact of market forces and competition on costs and prices. The problem identified is to examine how construction firms survive and grow, the competitive strategy they adopt, and the impact of competition on prices and costs.

Research aim and objectives

The literature review section briefly examined the literature on the UK construction sector and identified gaps in the subjects of the structure of the construction sector, construction costs, and competitive strategy. Three objectives are framed, and these are:

- To identify the market structure of construction firms, their subcategories and interrelations, and the impact that these firms have on costs.

- To evaluate construction costs for different projects and subcategories, the cost components, margins, and the effect of competition on these costs.

- To determine the competitive strategy used by large construction firms and the methods they use to obtain a competitive advantage.

Research questions

Research questions are framed to meet the research objectives and to evaluate the UK construction industry’s structure, costs and competitive strategies. The research will first examine the manner in which the construction sector is organised, including its various subgroups and categories, their informal and formal affiliations, and the bargaining power of these groups. The findings will help to understand the extent of competiveness among various sectors and the effect that this has on price and costs. The study will then focus on the cost components, payment methods, and financial exposure of these firms, and how they manage risk. The study will also help to understand the competitive strategies that large construction firms use to gain a competitive advantage. The following research questions are proposed.

- What is the extent of fragmentation in the UK construction sector and in various subsectors?

- What is the impact of this fragmentation on competiveness, cost, and margins?

- What competitive strategy do large construction firms use to gain a competitive advantage?

Research methodology

Considering the multiple variables that will be analysed, a structured framework is essential for the research. Core issues to examine are the structure of the UK construction industry, construction costs, and competitive strategies. Selecting between qualitative and quantitative methods is essential. For this research, qualitative methods will be selected since the extracted data are in the form of variables such as relations, groups, regions, costs, and performance metrics. These cannot be examined fully by quantitative methods. An inclusive list of variables will be prepared and secondary research will be used to find data for these variables. The data will then be analysed using contextual analysis and conclusions will be drawn to answer the research objectives (Walliman 2017).

Research type

Since the research involves examining multiple sets of data, a qualitative methodology will be used along with simple Excel calculations. Some interpretation of the data is required. Since case studies of large construction firms will be developed, a case study research approach will be used. Hence the study will use mixed methods with a combination of qualitative, interpretive, and case study approaches, and the main method of data gathering is through secondary research (Bryman & Bell 2015).

Sample and target audience

The research sample will consider sources such as peer reviewed journals, books, and websites from reliable sources such as the UK government and construction firms. A wide variety of these sources will be reviewed and care will be taken to access the latest publications or sources not more than three years old.

Anticipated tools

Tools considered for research include databases such as ProQuest, Emerald, and JSTOR, and websites of the UK government. While MS Office will be used, including Excel, AutoCad viewers will be downloaded to study drawings.

Data analysis

Data types will include values and contextual and descriptive key words, as per the predefined variables. Data will be analysed by using descriptive statistics and with contextual analysis in order to understand the impact they have on the construction sector. Some of the variables proposed are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Variables for the research.

Thesis timeline

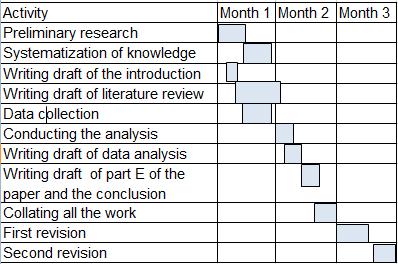

The Gantt chart in Figure 3 presents the project activities and timelines.

Conclusions

The proposal examined important aspects of the UK construction industry, including the structure and costs, and the competitive strategy of large customers. Several gaps were identified in the review, and further research can help to bridge these gaps. The recommendation is to begin the work on the full dissertation as per the timeline given in Fig. 3. The research will help to understand the dynamics of the construction industry and its competiveness, and the findings will help to address some of the problems that the industry faces.

References

Arcadis, 2017, International construction costs 2017: cost certainty in an uncertain world, Web.

Bryman, A & Bell, E, 2015, Business research methods, Oxford University Press, NY.

Construction Products Association, 2017, Construction industry forecasts 2017-2019, Web.

Cunningham, T, 2013, Factors affecting the cost of building work – An Overview, School of Surveying and Construction Management, Dublin.

Glenigan, 2017, Construction industry KPI report, Web.

Haynes, F, Construction statistics: number 18, 2017 edition, Web.

McGuckin, S, 2016, International construction market survey 2016, Web.

Ogunbiyi, O, Goulding, JS, & Oladapo, A, 2014 ‘An empirical study of the impact of lean construction techniques on sustainable construction in the UK’, Construction innovation, vol. 14, no. 1, pp.88-107.

ONS, 2017, Construction output in Great Britain: September 2017, Web.

RICS. 2017, Q3 2017: RICS UK construction and infrastructure market survey. Web.

Rhodes, C, 2015, Construction industry: statistics and policy, Web.

Zhigang, J, Fei, D, Heng, L, & Martin, S, 2013, ‘A practical framework for measuring the performance of international construction firms’, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, vol. 139, no. 9, pp. 1154- 1167.

Walliman, N, 2017, Research methods: The basics, Routledge, London.