Introduction

The United States of America Department of Veterans Affairs developed a significant policy regarding military veterans. There are many studies that discuss homelessness among veterans. The critical aspect is to uncover how homeless veterans handle chronic diseases based on the fact that they are homeless. The findings of this research will provide insights to the Department of Veterans Affairs and other policymakers in identifying effective programs that help solve chronic homelessness issues and ways to help veterans handle chronic diseases. The subsequent sections of this thesis include the background of the problem, the statement of the problem, the purpose of the study, the significance of the study, and the research question.

Background of the Problem

Homelessness has been a significant problem in the United States of America for decades. It became prominent in the 1970s and 1980s as military veterans also became part of the people suffering from homelessness (Perl, 2015). Various causes of homelessness were linked to this issue. These factors included demolishing a single room, which used to be called skid rows (Perl, 2015). This type of housing was majorly used by single men, and their destruction forced many people into the streets (Perl, 2015). The reduced availability of cheap housing has also increased the rate of homelessness in all groups, including veterans (Perl, 2015). Other factors that promoted general homelessness include the low likelihood of being hosted by family members, seasonal work, and changes in how admissions are conducted in standard mental hospitals (Perl, 2015). Homelessness has been grouped into short-term and long-term depending on how veterans access housing (Perl, 2015). Short-term occurs when they can access housing for a given period, while long-term is when the veterans cannot access accommodation for a significant period.

Homeless veterans risk getting involved in substance abuse disorders and other chronic health issues. Veterans after the Vietnam war, including those that participated in Iraq and Afghanistan, are affected significantly by homelessness (Perl, 2015). Individuals who were once heroines for their country are experiencing homelessness leading to their deaths on the streets (Perl, 2015). The notion surrounding the military that they have been equipped with educational benefits, training needed for a productive life, and other job training is portrayed otherwise as the population of veterans in the homeless population being significantly high.

The statistics on homeless veterans show that based on gender, men form the highest composition of homeless veterans. The composition of female veterans since 2009 has increased from 7.5% to 9.0%, with men having the highest percentage of 91.0% (Perl, 2015, p. 9). Based on veterans’ race, African Americans constitute the highest number of homeless individuals, with 38.8% of the overall population. Hispanic veterans represent 7.3%, and non-Hispanic white veterans include 50.2% of the veteran population (Perl, 2015, p. 10). Veterans aged 31 to 50 represent 36.1%, while those aged 51 to 60 constitute 42.9% of the total veteran group. Aged veterans with 62 years and above form the highest percentage of the homeless veteran population, with 54.1% (Perl, 2015, p. 10). Mental disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other chronic diseases that are either physical or mental are complex health problems that affect a considerable population of homeless veterans.

In 2018, the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) conducted research showing that 28% of veterans in the Veterans Administration health insurance program suffer from depression (GAO, 2020). 13% of the veterans suffered from PTSD, 19% were diagnosed with alcohol, and 20% were drug abusers (GAO, 2020). These factors extensively affect veterans, which promotes the risks of being homeless. Additionally, it makes it challenging for them to have employment, leading to homelessness due to a lack of income to pay for housing. GAO (2020) reports show that aging veterans are experiencing significant challenges because they are not part of the programs offered (GAO, 2020). The report also indicates that the number is expected to increase. This is because as the veterans get older, the programs they enroll in cannot cater to a higher level of care, making them find ways to live alone, and since they cannot afford it, they end up homeless.

The failure of the national policy regarding veterans hugely affects their lifestyle, as most end up on the streets. Homeless veteran statistics conducted in 2019 showed that approximately 21 out of the 10,000 were homeless in the United States of America (Moses, 2020). This rate is significantly higher than the homeless rate, 17 out of 10,000 (Moses, 2020). Although several programs have been introduced to help curb the issue, the number of homeless Black Americans has increased significantly (Moses, 2020). Other groups, such as Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiian, suffer from high rates of homelessness despite serving in the United States military. The COVID-19 pandemic also affected homelessness among veterans as it promoted unemployment and evictions. Most veterans lost their jobs because of the pandemic (Moses, 2020). This affected aged veterans profoundly as the pandemic was harsh on them compared to middle-aged individuals. Veterans suffering from disabilities were also affected, pushing them to homelessness.

Veteran homelessness has become a national health problem in the United States as most of them end up with chronic illnesses impacting their life quality after serving their country for a notable period. African American veterans face a significant challenge in receiving proper healthcare services (Crone et al., 2021). They face significant barriers which are attributed to racism. Similarly, most research has underrepresented the challenges of African American veterans.

Statement of Problem

From a public health, federal authority, and societal standpoint, homeless veterans are a significant population in need of aid. Although eradicating veteran homelessness has been a priority for a national policy for over twenty years, thousands of veterans sleep on the streets every night. Over 37,500 military veterans do not have a place to sleep on any given night, and around 120,000 use emergency asylum or temporary housing (Crone et al., 2021). Not only are there a disproportionate number of veterans among the homeless population, but there are also uneven numbers of African American veterans in the homeless community. Although veteran homelessness has decreased, it is troubling that the number of black veterans suffering homelessness has not changed considerably.

Veterans who are unable to find stable housing often have health problems. Those who have served their country and are now on the streets are at increased risk of developing mental health issues, contracting infectious diseases, and being exposed to harmful chemicals. Depression, diabetes, heart disease, hepatitis, respiratory disorders, arthritis, and high blood pressure are some chronic, untreated medical diseases that plague homeless veterans. Around 90% of homeless veterans suffer from untreated medical issues, drastically reducing their quality of life and leading to their untimely demise (Derderian et al., 2021). Few studies have focused on the health of homeless veterans of color.

Purpose of Study

The purpose of the current research is to do an extensive literature search on determinants that lead veterans to homelessness. Additionally, the study seeks to find the rate of chronic illnesses among veterans and how they handle the issue. Understanding this issue may help persuade lawmakers to adopt sensible measures to fix it. Healthcare providers and the public health sector face a formidable challenge in meeting America’s homeless veteran population’s multifaceted and complicated medical demands. There is sufficient evidence that shows how difficult it is for homeless people to get the best medical treatment possible (Tsai et al., 2019). Transportation issues, a lack of cheap healthcare options, and a disjointed network of healthcare providers and facilities all contribute to a lack of access. In addition, the veterans’ health care eligibility process is difficult to navigate inside their affairs system. The likelihood of a veteran receiving care depends on their health assessment. Compared to their military lifestyle, where they are seen as powerful, using healthcare services can be seen as a weakness.

Significance of the Study

The significance of this research is to fill a gap in the current literature by exploring why some veteran colleagues are homeless from the perspective of current military members. The study also seeks to identify the gap surrounding chronic illnesses affecting homeless veterans and their actions. The findings are important for public administration and policy because the views of service members may be beneficial in describing possible responses to the issue. Furthermore, the results and suggestions may aid in designing effective solutions for homelessness amongst military veterans, which means the research could help policy shift in veteran affairs. Researchers and policymakers may learn more from the findings on tackling the issue. Positive social change may result from a deeper comprehension of the phenomena, the dissemination of information about its risk variables, and the use of results to inform policy development.

The researcher of this study addresses many different aspects of homelessness, including its root causes and measures that should be implemented to remedy the situation. To better meet the needs of these underserved communities, this study will also shed light on the factors currently limiting their mental and physical well-being. Like other populations, veterans face a significant risk of homelessness when facing poverty, substance use disorder, and unemployment. These factors are aggravated when the veteran had previously participated in combat as they may develop PTSD.

Research question

The following are key research questions that guide this research:

- What are the determinants that lead veterans to homelessness?

- What are health conditions that majorly affect homeless veterans, and the causes of action taken?

Understand Homelessness Among Veterans

This chapter provides an overview of various researchers on homeless veterans. The first section of this chapter presents a historical overview of veteran homelessness to provide information on how homelessness among veterans dates back to the 1980s. It is still a critical problem in the United States of America. The second section shows the risks of veteran homelessness as perceived by multiple researchers. The third section provides Demographics of homeless veterans in the United States of America.

Historical Overview of Homeless Veterans

Homelessness among veterans is considered a major problem in public health in the United States. As per Livingston et al. (2019), it was first documented in the early 1980s after the civil war. Plans to curb homelessness among veterans have been a top priority during the past decades in the U.S. These efforts have gained significant success with declines in the overall homeless population size by almost half (Henry et al., 2020). Most of this reduction is associated with the successes made by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)-the department of Veterans Affairs Supported Housing (VASH) program, and the use of a Housing First (HF) strategy. The VA has used vast amounts of money on its programs with a focus on providing transitional and permanent housing for individuals facing homelessness instead of insisting on simultaneously or first taking care of other issues they may experience (Henry et al., 2020). This has been specifically seen in Delaware, Maryland, and Connecticut states which have been able to report having attained functional zero on veteran homelessness. This depicts that homeless veterans can easily get access to permanent housing, which reduces the problem.

However, even with the considerable progress made, there is still a significant number of veterans that are still struggling with homelessness. As per Derderian et al. (2021), approximately 552830 individuals were found to be homeless in 2018 in one night. According to Livingston et al. (2019), more than 14% of this homeless population accounting for over 37000 individuals, are veterans, which is a significant problem considering they comprise around 9% of the general population. Tsai et al. (2018) claim that this is evidence of the failure of the government to provide care for individuals that risked their lives to serve the military and country. Moreover, Derderian et al. (2021) argue that veterans, particularly the ones who served since the start of the all-volunteer force, were more prone to the risk of facing homelessness. The authors continued to explain that veterans have been overrepresented in the homeless population since the late 1980s. This is because of the special benefits allocated for them, including home-loan guarantees, VA health care as well as education and disability benefits

Even though the overrepresentation discrepancy has decreased with time, it remains confusing since homeless veterans are more likely to have been married or married, male, older, and have health insurance coverage. Additionally, veterans are better educated, and Caucasian compared to other adults in the same situation (Derderian et al., 2021). Homeless veterans have had work and employment history owed to their military service (Livingston et al., 2019). Therefore, this should make it less likely for veterans to be homeless compared to other adults considering the advantages that they possess.

In veteran populations, Black Americans are most disproportionately represented in homeless populations. According to Crone et al. (2021), community integration is a significant problem for a majority of veterans after obtaining housing. Because of systematic racism, Black American veterans may face additional challenges. In support of this, Redmond (2021) claims that African Americans always encounter unique difficulties, especially in getting access to appropriate housing and medical services to effectively take care of their medical services. Crone et al. (2021) further argue that as much as annual surveys reported that veterans were overrepresented among homeless individuals, African Americans were specifically disproportionally represented among homeless veterans. In addition, while the overall veteran homeless population decreased between 2018 and 2019, the number of Back Americans did not achieve any significant drop. In support of this, Keller et al. (2022) argued that being African American was directly linked with a 1.5 higher chance of increased homelessness in Veteran’s Health Administration (VHA) service users of the United States Department of Veteran Affairs (VA). This is to mean that being an African American increases the possibility of homelessness as compared to a White individual following the influence of ethnicity.

Causes or Risk Factors of Homelessness

Homelessness among veterans is associated with a wide range of risk factors. To begin with, lack of social support is regarded as a significant factor that contributes to or accelerates instances of homelessness among veterans (Metraux et al., 2020; Crone et al., 2021; Montgomery, 2021; Metraux et al., 2017). In addition, the dissolution of relationships, especially the first year after military discharge and being unmarried, increases the possibility of homelessness in veterans (Metraux et al., 2017; Ellison et al., 2016). As a result, these conditions make it difficult for individuals to support themselves after service, which might enhance the possibility of them ending up homeless.

The length of time after military discharge to homelessness (DTH) is a significant aspect among veterans. This is because homelessness is believed to occur close to the military discharge due to the loss of structure that the military provides and relocation (Crone et al., 2021; Montgomery et al., 2020). It is also linked with the transitions to civilian life as well as medical and mental health problems that were experienced during their service. Moreover, Tsai et al. (2020) argue that an increased lack of affordable housing in urban areas and challenges encountered by subgroups such as veterans with cognitive impairments and females with children can increase homelessness regardless of the DTH period. This is because, without adequate income, individuals will lack housing options and experience evictions and instability, which eventually will lead to homelessness.

Demographics of Homeless Veterans

Among the American veterans, most of those who face displacement are men. In a 2018 United States Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) report, 91 percent of those seeking shelter were male. The number is still high, with females making up less than 10 percent of the total population affected in the United States (Young, 2021). Gents over fifty who live in urban settlements are the most likely victims. Ladies are currently highly enrolled in the military hence increasing the number of female veterans. Women are not represented much among those facing shelter issues. The number of those homeless has been almost similar since 2006 (Stasha, 2022). Among the high number of men who are victims, about seventy percent are singles. Similarly, solitary females account for about three percent of the estimated total (Stasha, 2022). Gents are still the most represented category facing house problems in the general population.

The factors that have been significant causes of the high number of veteran men and women lacking homes include being unmarried, high cost of living, low level of social support after discharge, and psychological disorders. With the males occupying the most extensive portion followed by the women, the rest, which comprises about one percent of the total population affected, are transgender and gender non-conforming (Stasha, 2022). The total number of veterans in the USA currently ranges between forty and forty-five thousand. Gents are about thirty-seven thousand, women four thousand, and the rest is shared between the minority genders (Stasha, 2022). In a recent report by USICH, among the displaced ladies, veterans are at a much higher risk of experiencing homelessness than non-combatants. There is an over-representation of this category of females. Generally, older individuals above fifty, irrespective of gender, are highly affected.

Race

War heroes facing difficulties in housing are more likely to be of Black origin or any minority group than whites. In a 2018 report by USICH, African Americans had four times the chance of lacking a home. About one out of five victims throughout the country belonged to other racial groups, such as Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians, compared to whites. Racial disparities continue to be a significant obstacle though plans are in place to end the crisis. About 43.2 percent of the affected are people of color compared to 18.4 percent of the total war hero community (Southards, 2022). African Americans make up about 33 percent of the general veteran residents (Young, 2021). The Department of Housing and Urban Development recently released an analysis that suggested the over-representation of Hispanic and Black veterans in the shelter facilities compared to the total number.

Hispanics and Blacks are twice as likely to live in poverty than their white counterparts. Racial discrimination is still a big concern even to the nation’s war heroes. Native Americans are identified to be possessing three percent of the victim population, and the multiracial close to five percent (Montgomery et al., 2020). When the total number is considered, white heroes have a very slim chance of being displaced despite holding an enormous number among the affected former service members. In a news article by Young, it is stated that inequality emerges in every corner of the country, with the minority being the most affected. Here a testimonial of an older disabled veteran is given. He claims the government does not offer support, which is the primary factor resulting in housing problems.

Ethnicity

The United States of America contains two main ethnic groups, the Latino and the Non-Hispanic. About three-quarters of the total number experiencing home challenges were of Non-Hispanic ethnicity. Similar occurrences got witnessed in sheltered and unsheltered facilities indicating biases. In a 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) report, the number of Non-Latinos affected was about thirty-three thousand; this totaled 88 percent of the affected community (Stasha, 2022). Those protected averaged ninety-two percent of the total, about thirteen thousand. The unshielded was about twelve thousand, 83.3 percent of the total folk (Stasha, 2022). In the overall homeless society across the country, they make up 65 percent (Montgomery et al., 2020). The US Department of Housing and Urban Development analyzed it in 2020 and came to similar conclusions. Their data showed that the number of destitute Non-Hispanics was the majority among the community as it incorporated other ethnic groups such as African Americans, the natives, and the whites.

Veteran Hispanics affected among the total public is about a quarter. However, the share is still disproportionate as they do not make up a big community in the United States. The 2019 report by AHAR indicated that war heroes of Latino origin comprised about 12 percent of the entire society affected by lack of housing (Montgomery et al., 2020). Similarly, they comprised about 8 and 17 percent of the sheltered and unsheltered number of veterans, respectively (Stasha, 2022). Latinos comprise only seven percent of the total old-time heroes but nine percent lack proper homes. From the data presented, the number seems low, but it is high as the share is not comparable to the population of the minorities in the country.

Socioeconomic

Poverty plays a big role in increasing the number of veterans facing homelessness in the United States. Compared to the ten percent poverty rate of the adult population in the country, war heroes comprise about six percent. Income-relatable variables and low pay in the army are identified as potential factors resulting in the high number of old soldiers facing housing issues. The older warriors above 65 were the highly represented category among the veterans with an income below the poverty level. They totaled about half a million, while those aged between 18 and 34 were slightly above one hundred and twenty thousand (United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, 2018). The data showed an increase in those below the poverty line as the age brackets grew. With the high representation in poverty, affording good houses has been a big setback to the war heroes hence getting displaced to the streets.

Social factors affecting the population include drug and substance abuse, which results in housing problems. There is isolation and a lack of support from family, friends, or the government, which increases the chances of the vets going homeless. They tend to have low marriage and high separation rates, with one out of a possible five living alone. In a 2012 Veteran Affairs (VA) report, mental health played a part as most displaced had psychological disorders. About 16 percent of war heroes have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression (United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, 2018). The major consequence is the high treatment funds needed and misuse through drug abuse

Trait Theory of Homelessness

Trait theory is used in the current research to set the foundation. This theory provides the notion that individuals differ based on the fervidness and strength of the trait dimension. The criteria for characterizing personality traits include individual differences, stability, and consistency. This theory has significantly impacted the identification of the broad trait, plus providing explanations regarding their existence. According to Fleeson and Jayawickreme (2015), traits are personal variation concepts that are important in differentiating people’s character and behavior. The authors also argue that for a personality theory to be complete, it has to provide universal aspects of human characteristics which make people alike (Fajkowska & Kreitler, 2018). The common traits include categorizing a group of people, people in a given culture having a similar trait up to a given degree, comparing different people with a common trait, and categorizing individuals to a certain dimension.

Trait theory is applicable in this study because it explains the characteristics of veterans that affect their conduct, making them vulnerable to homelessness. Veterans’ traits are fashioned by multiple behaviors that affect their reactions to the environment. Trait theory is dynamic, which makes it accountable for the changes in veterans leading to homelessness (Fajkowska & Kreitler, 2018). Additionally, behavior type is attributed to be reliant on a particular trait. These factors make it possible for Trait Theory to give a rationale for the behavior of veterans.

Health Conditions Among Homeless Veterans

This chapter highlights health conditions among homeless veterans. Most of these individuals are exposed to medical conditions which significantly affect their physical and mental well-being. It is crucial for this research to show the health problems that homeless veterans encounter to provide possible ways of handling them. This chapter focuses on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, poly-trauma, chronic illness, substance use, mental illness, and comorbidity of mental Illness with substance use.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a form of mental illness triggered by past terrifying events that were either experienced or witnessed. PTSD affects many veterans that have traumatic experiences, especially ones in the homeless veteran population. Its symptoms can, at times, occur immediately after the traumatic event or can take years to manifest (Lucas et al., 2021). They can be classified into four main categories, including re-experiencing, avoidance, arousal and reactivity, and cognition and mood symptoms. Re-experiencing symptoms entails bad dreams, flashbacks, and frightening thoughts (Faria, 2018). Avoidance symptoms include avoiding things, people, places, feelings, or thoughts that bring up the traumatic experience. Arousal and reactivity symptoms comprise being easily startled, having difficulties sleeping, feeling on edge or tense, and frequent anger outbursts (Kennedy, 2019). Mood and cognition symptoms consist of unpleasant thoughts about oneself, which can lead to self-isolation, feelings of guilt, hopelessness, and shame, as well as lacking interest in engaging in activities (Jukić et al., 2020). These symptoms make it challenging for army veterans to maintain relationships and stable employment, making it difficult to afford housing hence leading to homelessness.

MST is referred to as sexual harassment or assault that happens to both veteran men and women during military service. It entails being forced into sexual activities either with promises of better treatment as a reward for sex or getting threats with negative consequences for refusing to provide sexual services (Lucas et al., 2021). Moreover, MST can also encompass individuals not being able to agree to sexual activities as a result of being asleep or intoxicated. Furthermore, MST can include unwanted sexual grabbing or touching or offensive remarks regarding a person’s sexual activities or body (Smith et al., 2020). All these MST encounters count as traumatic events that may have been experienced during service and can cause PTSD development, especially in homeless veterans that lack social support following isolation.

Male and female veterans who deal with PTSD and cannot have access to traditional housing do not necessarily come from a war zone. In most instances, veterans encounter trauma, even in non-combat situations like social isolation, sexual assault, or the effects of unmanaged substance use disorders (SUD) during army service (Kennedy, 2019). Possessing feelings of isolation can push veterans who struggle with PTSD to destructive self-medicating methods. Lack of effective treatment leaves veterans without help, even with isolation, alcoholism, or substance abuse. Self-medication using harmful means is common as a result of care and treatment neglect that many veterans with PTSD go through (Faria, 2018). Thus, with a lack of care and support, veterans with PTSD end up being involved in harmful activities that can drive them into homelessness.

PTSD symptoms make it challenging for military veterans to be able to sustain a solid family and peer relationships, which then hinders the social support situation in the form of strong social networks and positive reception for homecoming. Social support is an essential component among veterans that helps reduce the impact and brutality of PTSD symptoms as well as promote treatment outcomes (Kennedy, 2019). Upon discharge from the military, veterans that face conflict in their social setting have poor treatment outcomes (Jukić et al., 2020). Therefore, this leaves veterans suffering from PTSD in a challenging situation since strong social relationships help improve treatment outcomes. The symptoms of PTSD add to the dysfunctional and stressful family or social environment, especially in homeless veterans, which limits the development of familial support, thus hindering the process of healing.

PTSD can result in emotional numbing, which hinders the development of family functioning. As per Sippel et al. (2018), emotional numbing is the collective of symptoms that are manifested with reduced interest in significant activities, estrangement from peers, or feelings of detachment. Therefore, veterans that exhibit emotional numbing tend to have decreased levels of social support, which limits the healing process of PTSD. Moreover, emotional numbing can cause further emotional withdrawal symptoms among homeless veterans leading to social isolation creating difficulties with the treatment of trauma (Kennedy, 2019). Decreased interest in activities leads to low employment performance, such as low productivity. Additionally, PTSD makes it impossible for individuals to make regular appearances in the workplace, increasing the rates of absenteeism. Low productivity, combined with higher rates of absenteeism, makes it challenging for individuals to maintain their occupations due to poor work performance affecting their quality of life as they are unable to afford housing (Amosu, 2021). Furthermore, veterans experiencing PTSD lack time management ability and cannot form social interactions, which are essential factors needed in job performance.

Poly-trauma

Polytrauma is when an individual experiences severe injury in various organ systems and body parts, mostly associated with blast-related events. The sustained often have severe consequences such as significant disability or even death (Laughter et al., 2021). Some of the polytrauma conditions that patients can encounter include a case of traumatic shock or hemorrhagic hypotension and serious damage to not less than one vital function of the body. According to Wehman et al. (2019), at least one incurred injury has the capability of endangering the life of a polytrauma patient. These injuries mostly include burns, traumatic amputations, traumatic brain injury (TBI), damage to internal organs, as well as orthopedic trauma. Polytrauma injuries often result in cognitive, psychosocial, physical, and psychological impairments.

Military members are often exposed to injury-related events upon deployment into service, most of which non-deployed individuals and civilians cannot encounter. These events can include a warzone setting with controlled denotations, rocket-propelled grenades, as well as improvised explosive devices (Martindale et al., 2018). Compared to civilian and non-deployed settings, a deployed environment contains increased alterations in sleep patterns, physical stress as well as psychological stress, which greatly impacts the health of an individual. Moreover, the military culture limits reporting of polytrauma injuries such as TBI-associated symptoms, which may inhibit a return to active duty, which can prolong the development of the condition due to lack of the needed care.

The United States wars for Operation 58 Enduring Freedom–OEF and Operation Iraqi Freedom-OIF for Afghanistan and Iraq contributed to a significant number of TBI injuries. In these two wars, modern body armor was able to protect the U.S. military from explosion-related deaths using, but they still got brain injuries (Wehman et al., 2019). The Department of Veterans Affairs founded five Polytrauma Rehabilitation Centers (PRCs) in 2005 to aid in the rehabilitation and treatment of veterans experiencing TBI by enabling case management and offering in-patient care

In other instances, individuals having TBI alone instead of other mental conditions can have problems reconnecting into the community and increasing unemployment. These individuals find it difficult to form social relationships and manage independent living, which interferes with their quality of life and recovery process. Challenges in establishing social relationships translate into a lack of support and difficulties sustaining employment (Pugh et al., 2018). Therefore, veterans suffering from severe TBI find it challenging to transition from military life to a more civilian one the following discharge from service.

Employment is an essential aspect of the community, accompanied by more financial freedom, quality of life benefits, high self-esteem, a sense of contribution to society, and access to social groups or circles. According to Wehman et al. (2019), members of the veteran population that manage to maintain a stable work possess greater motor and cognitive independence and decreased self-report depression, anxiety, neurobehavioral symptoms, and anxiety-associated symptoms compared to ones with an unstable source of income. The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in 2017 that almost 24% of veterans, amounting to 4.9 million individuals, suffer a documented deployment-related disability (Wehman et al., 2019, p. 276). 4.3% of these individuals continued being jobless, with further unemployment rates influenced by the type of injury and age bracket. For instance, 59% of the unemployed post-service members were aged between 25 to 54.5 years (Wehman et al., 2019, p. 276). In addition, only 20.5% of service members and veterans experiencing TBI in a sample of 293 individuals were employed one-year post-injury, and resumption to duty was longer estimated at 6.5 months (Wehman et al., 2019, p. 276). Therefore, it is evident that vocational support services are necessary to help match the distinct needs of homeless veteran populations.

Active-duty service members and veterans face diverse barriers to community reintegration after an encounter with polytrauma-related TBI, just like non-military groups. These challenges are attributed to TBI experiences of unknown severity, especially in Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) or Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) combat Veterans (McGarity et al., 2017). Comorbidity with other psychological conditions also hinders veterans from successfully reconnecting with society, particularly in ones that result from deployment and combined with TBI problems (McGarity et al., 2017). With a history of traumatic brain injury, post-deployment adjustment challenges can also make it difficult for veterans to reintegrate into society (McGarity et al., 2017). Therefore, the challenges encountered in community reintegration result from TBI, psychological comorbidities as well as adjustment difficulties after discharge from service.

Chronic Illness

The common health conditions experienced by homeless veterans include cancer, diabetes, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hypertension. Moreover, veterans can be plagued by frostbite, ulcers, and malnutrition which are mostly associated with the general features of homelessness (Weber et al., 2018). The growing population of homeless veterans poses a significant challenge for the general public health department and healthcare professionals to effectively deal with their complex and multidimensional health needs.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is regarded as a key cause of increased mortality rates in the homeless population. The management of CVD is significantly challenged by adverse social circumstances as well as the collection of complex comorbidities often witnessed in homeless populations (Baggett et al., 2018). Thus, the management of CVD requires a multidisciplinary, creative, and flexible approach that can accommodate all the associated factors to help enhance the effectiveness of the management process. As per Baggett et al. (2018), the prevalence of hypertension is comparable in both homeless and non-homeless populations. However, hypertension in homeless veterans is mostly untreated or undiagnosed, which is attributed to poor blood pressure management than in the non-homeless population (Baggett et al., 2018). In the same case, diabetes prevalence is similar in both the general and homeless populations, but challenges to glycemic management in the latter lead to terrible condition control and severe complications.

Homeless veterans also suffer from HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV). As per Noska et al. (2017), 1.42% of a population of 1,791,065 veterans are positive for HIV. In addition, 5.8% tested for HCV in 3,120,350 veterans, while 0.84% of 1,506,051 veterans were positive for HBV (Noska et al., 2017). These numbers depict that HIV, HBV, and HCV prevalence in veterans is significantly higher compared to the general U.S. population. Homeless veterans suffering from HIV, HCV, and HBV are able to easily access healthcare services that can better align with their needs. However, this is not always the case, as some individuals are not able to receive treatment and management services due to various factors such as eligibility and transportation costs.

They possess differential access to the needed care, which affects their capability to manage their chronic illnesses, which is influenced by various factors. Most homeless veterans find it challenging to get a hold of health insurance, particularly in nations that have not yet embraced the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion which limits access to medications associated with chronic illnesses (Tannis & Rajupet, 2021). Additionally, access to adequate healthcare services among veterans is attributed to a lack of affordable medical care, transportation barriers, and service fragmentation in healthcare providers and institutions.

Lack of affordable, stable housing also influences the increased complication levels in chronic health conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. The severe complications experienced include death following ischemic heart disease as well as more hospitalizations as a result of diabetic problems (Tannis & Rajupet, 2021). These chronic illnesses are characterized as ambulatory care-sensitive conditions (ACSCs). ACSCs are considered medical issues normally treated mainly in non-acute environments such as in physician clinics and offices (Tannis & Rajupet, 2021). However, if they are poorly managed, complications can increase the likelihood of resulting in unnecessary hospitalizations. Some of the most common ACSC issues include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, asthma, hypertension, and congestive heart failure.

The increasing respiratory illness problems, such as asthma among homeless veterans, are attributed to environmental allergies, extreme temperature conditions, and pests due to the poor quality of transitional housing settings. Moreover, transitional living arrangements among homeless individuals expose veterans to second-hand tobacco smoke, which can accelerate chronic health risks (Tannis & Rajupet, 2021). Additionally, homeless individuals spend more time in open spaces, which exposes them to environmental particulate matter and air pollutants which increases the likelihood of COPD and asthma development among veterans.

In an attempt to address the increasing rates of chronic health conditions among veterans, President Barrack Obama and former Veterans Affairs Secretary Eric Shinseki established a goal in 2009 to reduce and curb chronic homelessness. The program was focused on outreach, prevention, education, treatment, community partnerships, employment and benefits, and housing which would provide support to deal with associated illnesses as well as homelessness (Weber et al., 2018). The set plan was aligned with the importance of curbing nationwide homelessness in the U.S. veteran population and making contributions to improve their quality of life.

Chronic illness is persistent among homeless veterans as they are exposed to harsh conditions. In a study conducted by O’Toole et al. (2018) with 266 veterans, 83 in Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT) and 183 in Homeless Patient Aligned Care Teams (H-PACT), 86% of the veterans reported not less than one chronic health condition. Findings indicated that 33.1% of veterans suffered from hypertension, 24.2% experienced asthma or emphysema, 33.1% had hypertension, and 25.3% had liver cirrhosis or hepatitis problems (O’Toole et al., 2018).

Substance Use

One commonly abused drug is an opioid treatment which is mostly prescribed to help veterans manage chronic pain or service-related injuries. Opioid addiction in military veterans starts with a pain description due to an injury obtained during deployment (Osborne et al., 2022). However, since opioids are addictive in nature, especially when coupled with mental health problems experienced by veterans, they tend to overuse the drug promoting its abuse. Therefore, military veterans can develop a dependence on opioids which can then influence addiction leading to substance use. Moreover, some veterans tend to use marijuana in an attempt to reduce PTSD symptoms. According to Hill et al. (2021a), more than half of the states in the U.S. legalized the possession and sale of cannabis both for recreational and medicinal purposes. Faria (2018) claims that substance abuse has been directly associated with homelessness, suicide risk, trauma, physical health problems, difficulties sustaining relationships and work, and mental health disorders among veterans. In veteran populations, drug use can include prescription or illicit.

This liberalization of marijuana laws may have extremely influenced U.S. military veterans considering they are more likely to report the use of medical cannabis as compared to civilians following their experiences with traumatic events (Davis et al., 2018a). Moreover, homeless veterans tend to have increased rates of psychiatric disorders which are associated with cannabis use. As per Hill et al. (2021b), excessive cannabis use can be harmful when abused for longer periods of time. Marijuana is associated with medical problems such as impaired or short-term memory, chronic bronchitis, impaired motor coordination, and lack of ability to successfully perform complex psychomotor activities such as driving.

During military service, some service members drink in culture to celebrate combat victories with regard to their social settings or to mask the trauma they are experiencing. Alcohol is considered a customary culture in the military. As per Gibson et al. (2021), military members drink on diverse occasions, either leisurely or socially, to depict their celebration of an event, such as a promotion, or to foster camaraderie and unity in their battalions. Furthermore, military bases promote easy access to alcohol at reduced prices which fosters its consumption which can quickly turn to dependence even after discharge from service. On the other hand, combat exposure and deployments lead to increased rates of alcohol consumption in military service (Osborne et al., 2022). Veterans tend to utilize alcohol as a mechanism for coping after their experiences with traumatic and stressful events during and after their time of service. Some veterans also use alcohol to self-medicate the issues associated with mental health issues such as depression or PTSD.

Following the military’s strict rules to zero tolerance policies concerning substance use which is enforced by random and frequent testing, illicit drug use is low in the military than in the civilian population. However, this is not the case with alcohol or tobacco, which are more acceptable in society or the military culture (Faria, 2018). Moreover, opioids are prescribed by medical practitioners to help service members cope with pain to foster faster recovery to enable them to return faster to active duty in the war effort (Colloca et al., 2021). With time, the military members will then develop a dependence on these drugs to help them manage their pain which promotes increased substance use even years after discharge.

Homeless veterans experience social pressures that force them to bury negative emotions like depression by silently enduring them and masking them with drinking. This then leads to dependence on alcohol to make them feel better and, over time, can shift to alcoholism (Colloca et al., 2021). Alcoholism is where individuals will continue to drink even with the associated severe consequences to their own lives and those of others, especially when one is trying to hie a traumatic. According to Colloca et al. (2021), when veterans use drugs or alcohol to help deal with their emotions, they tend to exhibit significant personality changes. This is specifically evident in individuals suffering from traumatic brain injury (TBI), PTSD, or experiencing some kind of physical pain, mostly from injuries.

Veterans can also hide behind the wall of substance abuse following their inability to connect socially. Upon discharge from the military, veterans can face difficulties in reconnecting with their peers or families and end up engaging in substance abuse to mask this problem (Faria, 2018). Veterans often experience a unique kind of stigma that differentiates them from the civilian populations (Faria, 2018). This is mostly worsened by the lack of communication between civilians, veterans, and military personnel, also known as the civilian-military disconnect. When veterans return from combat deployments, they often feel misunderstood and alienated, making it difficult for them to connect socially. They end up using substances to fill this void of loneliness.

Furthermore, veterans can experience stigma influenced by their fellow peers or authority figures regarding seeking treatments for either PTSD, depression, or other illnesses as they will be considered weak for needing medication. Following this, veterans and military personnel will tend to turn to substance use for self-medication to maintain how they are perceived as strong by others (Faria, 2018). In addition, veterans who have experienced trauma find it difficult to maintain a steady income source, leading to frustrations and turning to substance use to help deal with these problems.

Mental Illness

The prevalence of mental illnesses such as anxiety, depression, and psychosocial distress is significantly high in the homeless population. A study by O’Toole et al. (2018) found that 78.1% of 266 veterans suffered from at least one mental health problem with reported at least one mental health condition, with 63.2% suffering from anxiety, 50.8% having PTSD, and 69.2% experiencing depression. Baggett et al. (2018) argue that a quarter of homeless individuals suffer from chronic mental illnesses such as severe depression, schizophrenia as well as bipolar disorder (Baggett et al., 2018). Apart from disrupting veteran lives, these chronic mental illnesses hinder cardiovascular disease (CVD) manifestation and diagnosis by obstructing reporting of symptoms and executive ability to complete diagnostic tests and interfering with motivation or capacity to find medical care. Mental illness in homeless veterans is influenced by diverse factors related to military service, including environmental stressors as well as traumas and injuries incurred over wars (Pasinetti et al., 2021). Moreover, individuals suffering from chronic mental illnesses tend to smoke a lot in an attempt to curb their symptoms which can aggravate the cardiometabolic risk factors, including diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia, which enhance the development of CVD.

Depression is a major mood depression condition affecting both the veteran and general populations. The prevalence of depression in a lifetime is approximated to be 21% of the total population (Shawler et al., 2022). Incidence in females is estimated at 25%, while that of males is at 12% (Shawler et al., 2022). Veterans from the Gulf War report have double the risk of developing depression disorder compared to the general population. The likelihood of developing depressive symptoms rises with an increase in conflict experiences as members are deployed into service away from their families and friends and subjected to new stressors. 15% of battalions returning from service reported experiences with depressive-related symptoms in 2012 (Shawler et al., 2022). With the prolonged war in Afghanistan, the growing homeless veteran population with combat experience presents the need for the availability of mental healthcare services to help individuals manage their symptoms (Finnegan & Randles, 2022). Service providers must take into consideration that upon discharge from the war, veterans come back with physical injuries as well as psychological issues such as depression and acute stress disorder, which can interfere with their daily activities.

Additionally, the military setting promotes the progression and development of depressive symptoms. The military environment separates individuals from their families and social support systems, thereby increasing the stressors of deployment combat and pushing individuals to put themselves in harm’s way in service of their country (Shawler et al., 2022). Therefore, active duty exacerbates the risk of depression among veterans as well as active military members. For instance, military medical facilities reported an increase in diagnosed depression rate of 15% following placements in Afghanistan and Iraq (Shawler et al., 2022). Such a high prevalence necessitates an increased need for healthcare services, especially for homeless veterans, to help deal with problems associated with mental illnesses.

Comorbidity of Mental Illness with Substance Use

Comorbidity is where two conditions, such as substance use disorder (SUD) and a specific mental health illness, coexist together in an individual. The presence of substance use disorder (SUD) and mental illness, also referred to as co-occurring disorders, is particularly among the homeless veteran populations. This is to mean that many people with drug addictions also suffer from an underlying mental health condition (Hill et al., 2021a). The changes that occur in the brain following substance use occur in the same areas affected by anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia. Whereas comorbidity is a complex link, there are mental health issues that promote the risk of experiencing substance abuse among homeless veterans. According to Ecker et al. (2020), individuals suffering from mental illnesses tend to seek help from drugs and alcohol to help them deal with the pain associated with their mental health problems. Moreover, self-medicating efforts to help relieve symptoms or manage stress make veterans more susceptible to substance use.

Cannabis is one of the most abused drugs in the world, particularly among homeless veteran populations. Increased marijuana use is linked with exposure to traumatic events and related psychiatric problems, including anxiety, suicide ideality, and mood (Hill et al., 2021b). As per Ecker et al. (2020), 80% of homeless veterans that use cannabis also suffer from at least one mental health disorder, and this comorbidity was accompanied by more utilization of mental health services among this group. In support of this, Lucas et al. (2021) argue that PTSD is a common health condition observed in the U.S. military, especially in the groups that are mostly exposed to combat. To deal with the symptoms, the veterans are inclined to use marijuana to help them forget the traumatic events in an attempt to improve their quality of life.

A person’s vulnerability to substance abuse can, at times, be attributed to genetics. A large part of this susceptibility results from complex interactions among various genes or between genetics and environmental influences (National Institute of Drug Abuse, 2020). For instance, increased use of cannabis in the adolescent stage is linked with the risk of developing psychosis in adulthood, particularly in individuals that carry a specific variant of the gene for catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) (López-Martín et al., 2022). COMT is an enzyme that damages neurotransmitters like norepinephrine and dopamine, which then influences immediate psychotic or cognitive effects associated with cannabis use.

Environmental influences also contribute to the occurrence of comorbidity in mental illness and substance use among homeless veterans. The environmental factors linked with the risk of mental illnesses and substance use include trauma, severe childhood experiences, and chronic stress. Military personnel experience serious trauma as well as stress following the nature of their army roles (Thomson, 2021). Stress is a common risk factor associated with diverse mental health such as depression and anxiety. Therefore, this provides a common neurobiological link between mental conditions and substance use disorders (Ding et al., 2018). Moreover, extreme exposure to stressors enhances relapse to drug use following recovery periods. The stress mediators always intercede in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which can affect the brain circuits responsible for regulating motivation (Hinds & Sanchez, 2022). Additionally, higher stress levels decrease prefrontal cortex activity and enhance the responsiveness in the striatum, which improves impulsivity and reduces behavioral control, fostering vulnerability to substance use disorders. Emotionally and traumatized individuals such as veterans tend to suffer more from PTSD and are inclined to use drugs in attempts to avoid tackling trauma and its consequences and reduce the associated anxiety.

The second pathway to comorbidity is that illnesses can influence the occurrence of substance use. People that suffer from mild, severe, and subclinical mental issues tend to self-medicate using drugs. Some of the drugs may be able to reduce the symptoms associated with mental illnesses such as PTSD but can also aggravate these symptoms (Williamson et al., 2021). For instance, frequent use of cocaine can exacerbate bipolar disorder symptoms and promote the development of the condition (Lortye et al., 2021). Veterans mostly use cocaine to help deal with the discomfort brought about by trauma which can then promote dependence over time. Therefore, when a person suffers from a mental condition, the accompanying changes in brain activity may foster susceptibility to problematic substance use by decreasing the uncomfortable symptoms of the mental illness and fostering their rewarding effects.

Lastly, substance use and addiction can create a pathway for the development of mental illnesses. According to Stoychev (2019), substance abuse can result in changes in some regions of the brain, disrupted in other mental conditions like mood, anxiety, and schizophrenia. Drug use before the manifestation of the first mental illness symptoms can lead to changes in brain function and structure that trigger a causal predisposition for the development of the mental issue. For instance, recreational cannabis use is linked with an increased likelihood of psychosis development.

Research Methodology

Research methodology forms the basis of data collection in research as it highlights the steps that the researcher took. This chapter highlights areas covered before, during, and after data collection. It outlines the research philosophies selected, the approach used, and the search strategy employed in finding literature materials. The methodology used is critical in informing the findings, and the conclusion is drawn from the previous research.

Research Type

Research categories are categorized into explanatory, descriptive, and exploratory. Explanatory research is a type of research where the information available is limited, and it explores the existence of a particular topic. Furthermore, it focuses on predicting the occurrence’s future outcome (Dudovskiy, 2022). This type of research can also be described as cause and effect as it checks on trends in the available literature data that have not been explored. Descriptive is a category of research focusing on understanding the “what” as it has a basis in literature. Exploratory is a research type that investigates a topic that has not been clearly defined in the literature. It is used to investigate the existing problem despite not being able to provide conclusive arguments on the findings (Thomas & Lawal, 2020). This research begins with a general idea of the issue being investigated. This type of research is flexible as the researcher can change depending on the available data (Dudovskiy, 2022). It seeks an explanation of why and how based on insights from the literature. The current study utilizes exploratory research to explain the determinants of homelessness among veterans, the health conditions surrounding them, and how they handle them.

Research Philosophy

Research philosophy is a way in which data about a given topic is supposed to be collected, analyzed, and used. The selection of the research philosophy in the current study is directed by the research questions being investigated and the type of research. It guides the research questions to be examined and the critical decisions that the researcher is supposed to make. Selecting a research philosophy is critical as it maintains the study’s credibility. However, researchers have an opposing view on the type of research philosophy that should be used when investigating a particular concept. This makes the current study have a philosophical stance applied in the present study.

Ontology

Ontology research philosophy focuses on the existence and nature of being. It is perceived as research thinking on the fundamental nature of reality, specifically the social reality. The beliefs are usually described using dichotomy, where objective reality uses independent observers while subjective reality applies group negotiations (Shaw, 2018). This results in the realistic or objectivist and anti-positivist ontology. The anti-positivist ontology is most prominent in social theory despite facing variations across time and regions. Ontology helps inform social research as most ontological questions are applied (Vogl et al., 2019). For instance, the positivist may query the cause and effect, while the anti-positivist queries the variation in meaning and explanation. Researchers have to incline to a philosophical stance to avoid the research being incoherent.

The objectivist perspective is that social entities exist independently and are not affected by social actors. Constructivism or subjectivists believe that the existence of a social phenomenon is directed by the actions taken by the social actors (Shaw, 2018). The study utilizes constructivism based on the perspective that the knower makes the world (Vogl et al., 2019). Homelessness among veterans is a result of multiple factors that social actors control. This makes this standpoint critical in understanding the causes and health issues among homeless veterans.

Epistemology

Epistemology is a philosophical branch that focuses on the way knowledge was gathered and the type of sources that were used. When conducting research, the view of the world affects the interpretation of data by the researcher, making it necessary to have a philosophical standpoint from the onset of research. Epistemology refers to the underlying assumptions in knowledge and how the researcher discovers the present world (Shaw, 2018). It makes it possible to make sense of the data as it involves nature and form. This philosophy has two branches which include positivism and interpretivism. The principle of positivism focuses on knowledge and the world. It involves data collection based on statistics of the gathered data.

The positivist approach uses hypotheses and deductions as it perceives the data objectively. It involves generalization as collected data is used to inform specific characteristics of the general population. Interpretivism focuses on answering a research objective in a positivist world where the researcher believes there is a need. In this subbranch, the researcher plays a role in research through data interpretation (Shaw, 2018). In interpretivism, the researcher is influenced by the environment and acknowledges reality. This philosophical perspective is subjective, making it impossible for generalizations as it is accompanied by biasness. The current research opts for interpretivism as it seeks to identify the issue surrounding homeless veterans based on the available research materials.

Research Approach

The research approach can either be deductive or inductive. The deductive approach employs theory formulation using a hypothesis where the researcher uses a hypothesis. The inductive approach utilizes data collection, which the researcher analyzes to develop a theory based on findings (Woiceshyn & Daellenbach, 2018). The inductive approach is usually employed in qualitative research, while the deductive approach is used in quantitative analysis. Quantitative research usually employs the deductive method to inform the existing data. Qualitative research is generally driven by perspective and ideas leading to the inductive development of the theory (Bonner et al., 2021). Deductive methods begin with the generalization of concepts and seek instances where they can be applied to a specific view. The variation between qualitative and quantitative applications of the research approach is determined by testing, theory building, and scientific reasoning (Woiceshyn & Daellenbach, 2018). The current research utilizes an inductive approach by collecting relevant data on homelessness among veterans. After collecting suitable and enough data, the researcher identifies patterns in the existing data, coming up with a theory that explains data patterns. This results in a transfer from data to theory as per the findings depicted by the data collected.

Research Method

In research methodology, the research method can be either quantitative, qualitative, or mixed method research method. The quantitative research method is used when collecting numerical data (Borgstede & Scholz, 2021). It is used in the identification o numerical patterns in the data, testing causal relationships, and making predictions. It is used to identify the relationship between variables in a population to make inferences from the data (Ahmad et al., 2019). Qualitative methods inform beliefs, attitudes, behavior, and experiences as they involve collecting non-numerical data (Borgstede & Scholz, 2021). Mixed method research uses qualitative and quantitative methods to collect numerical and non-numerical data. The current study uses qualitative meta-analysis where relevant published materials are included in this research.

Data Collection Procedure

Search Strategy

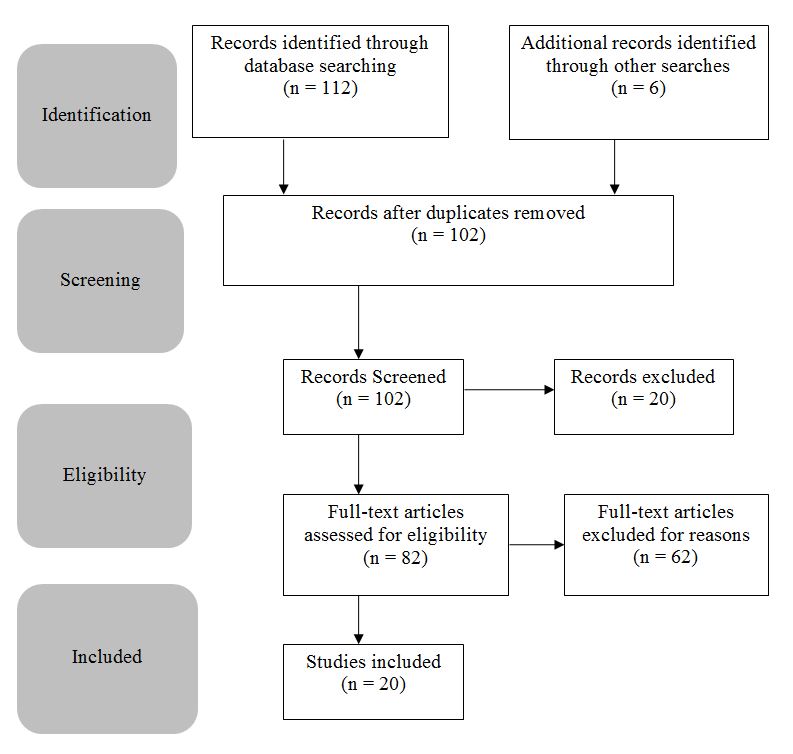

The current study used various keywords such as “veteran homelessness,” “Health conditions in homeless veterans,” “chronic illness in homeless veterans,” “mental health issues in veterans,” “polytrauma among veterans,” and “PTSD in homeless veterans.” Other keywords include “Causes of homelessness in veterans” and “risk factors in homeless veterans.” The researcher used the keywords to explore various online libraries such as PubMed, Google Scholar, World Public Library, Science Direct, Scopus, and Digi Library. Other websites, such as governmental and department of veteran affairs publications, are also scooped for relevant research materials. The selection was limited by the period based on the available materials in the investigated area. The research was refined, leading to the identification of 112 articles. Six more articles were collected from the school library resulting in 118 articles. These articles were then checked for duplication reducing the final number to 102 research materials. The remaining articles were screened, and 20 were removed as irrelevant. Eighty-two articles were then checked for eligibility by checking their abstracts, resulting in the removal of 62 materials.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria include and exclude research based on the researcher’s set criteria to ensure that the research is within the scope. Research materials that provided information on homeless veterans and health conditions were included. Articles that did not include homeless veterans or those that mainly focused on general homelessness were not excluded. Furthermore, materials within the last five years were prioritized, with some inclusion in those published up to 2015, depending on their relevance. This provides the current research with recent information on homeless veterans. Unpublished articles, research summaries, reports, and abstracts were also excluded. Only materials which were published in the English language were included.

Data Analysis

The research approach selected by the researcher guides the qualitative analysis. It determines whether a complex technique can be used (Purssell & Gould, 2021). The methods used in the qualitative analysis include discourse analysis, thematic analysis, narrative analysis, explanation building, and content analysis. The research approach and the technique used in data collection limit the current research to utilize thematic analysis (Woiceshyn & Daellenbach, 2018). The method entails searching datasets to identify repeated patterns in various research. The method includes data interpretation when creating codes and developing themes. In secondary research, thematic analysis involves three stages. The first step is the line-by-line coding text from the research material (Purssell & Gould, 2021). The second step is the development of descriptive themes, which will be included in the analysis, and the last step is the creation of analytical themes, which the researcher uses to develop hypotheses, explanations, or interpretations (Purssell & Gould, 2021). The final stage is critical in synthesizing findings (Purssell & Gould, 2021). This thematic analysis is significant in concluding the patterns generated in the data.

Findings and Analysis

This chapter highlights the findings of the literature materials which are included in the current study. It groups the findings of the materials based on the themes that are generated. This section is crucial in informing the research questions as it provides information that answers the research question as per the research materials that have been selected. Thematic analysis helps organize this section based on related findings.

Determinant of Homelessness Among Veterans

Veterans that receive a discharge with dishonorable discharge are more likely to become homeless as compared to their counterparts with honorable status. A less noble release from service interferes with veterans’ VA benefits which deny them housing support promoting homelessness in veterans. These individuals lack VA support following lack of eligibility due to misconduct during military service (Tsai & Rosenheck, 2018). Separations from the military due to misconduct issues are associated with severe outcomes such as homelessness in veterans.

Misconduct issues make it challenging for individuals to reconnect with civilian life, which can often lead to social isolation and, eventually, homelessness. Moreover, early discharge from the military following misconduct issues interferes with eligibility for receiving VA support such as housing and healthcare services, thereby impacting the quality of life of individuals. Additionally, misconduct problems can be associated with a variety of risk factors that influence the likelihood of homelessness among veterans, such as substance and alcohol abuse, history of criminality, and unemployment (Gundlapalli et al., 2015). It is also related to post-deployment financial instability, mental health issues as well as adverse deployment experiences such as trauma. Getting stable employment can be a challenging issue for the veteran population, especially if the individuals report a history of misconduct during their period of service.

Adverse trauma-related placement experiences that can result in mental illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder and depression make it difficult for an individual to successfully reintegrate into the community and maintain social relationships and employment. Following this, a dishonorable discharge from service translates to no VA benefits, which then enhances homelessness in the veteran population (Gundlapalli et al., 2015). Additionally, a lack of VA healthcare services can make it challenging for individuals to manage their chronic illnesses, such as PTSD, with the capability of interfering with an individual’s life, such as difficulties in maintaining employment. With a lack of a stable source of income, veterans will find it hard to afford housing and other basic needs such as food which will eventually push them into homelessness. Moreover, separation from the military following misconduct without retirement benefits, such as a retainer benefit, can put individuals at financial instability or disadvantage, meaning they cannot be able to manage their housing.

A history of criminality can negatively impact an individual’s opportunity to be employed or maintain a job which lowers their disposable income and interferes with their ability to maintain proper housing. Moreover, most veterans self-medicate to help deal with or manage chronic pain and health conditions which in turn can promote addiction to substances such as opioids. With a lack of VA support following misconduct upon discharge, veterans cannot be able to afford their housing and medical services. Due to this, veterans tend to encounter competing priorities where they are forced to compare the costs of seeking housing and healthcare to what is needed to meet their basic needs, such as food (Shulman et al., 2018). Homeless veterans are more inclined to secure essential priorities that rank higher on their needs lost and then solve ones that are not that argent, such as medical care.

Sexual Trauma

Some veterans in both male and female genders indicate having suffered military sexual trauma (MST) over their period during service. MST is associated with severe outcomes upon discharge from service, including depressive symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder. Moreover, MST experiences are accompanied by lower quality of life and poor family relationships. These outcomes have the potential of an individual’s life, such as difficulties maintaining employment and social relationships, especially when not supported by the VA. A lack of employment can hinder an individual’s ability to maintain proper housing to keep them off the streets. Moreover, MST results in psychosocial consequences such as lack of social support, revictimization, and involvement in criminal activities, as well as post-military adversity (Brignone et al., 2016). These factors increase the risk of housing and financial instability, which can easily force veterans into homelessness. Without a lack of social support and care, individuals find it challenging to treat and manage their illnesses, such as PTSD and depression, which obstruct their efficiency in carrying out their daily activities, such as work.

Military sexual trauma is regarded as a significant factor in influencing potential problems to successfully reconnect into society. MST can force individuals into substance and alcohol abuse and develop mental health problems like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, psychosis and distress, and more serious mental health comorbidity (Kessler & Gearhart, 2021). Individuals neglect seeking treatment for these conditions following discrimination associated with their experiences which can then escalate and significantly obstruct their daily lives.

Moreover, MST is associated with avoidance symptoms, where individuals tend to avoid thoughts, people, feelings, or places that might remind them of their traumatic events related to sexual assault and harassment. This can make them lose opportunities that could have improved their lives. In addition, MST is accompanied by unpleasant thoughts towards oneself, resulting in hopelessness, shame, feelings of guilt, self-isolation, and lack of interest in participating in activities (Jukić et al., 2020). These symptoms influence people’s motivation to find job opportunities that can help them improve their quality of life and evade homelessness.

Race

Most of the minority groups in the U.S. report higher rates of homelessness compared to the whites hence attributed to a disproportionate share of the population. Homelessness among veterans is regarded as a significant public health issue, especially among African Americans and Hispanics. African American veterans particularly experience unique difficulties in getting access to adequate medical care services to help meet their necessary health needs (Crone et al., 2021). As much as homeless veterans may attain eligibility for VA support services, they may still choose not to utilize them, especially among African American individuals (Derderian et al., 2021). Moreover, they tend to receive less follow-up care following diverse factors such as unavailability of timely appointments, staffing issues as well as prioritization of some veterans.

Distrust is another factor that can hinder African American individuals from accessing the necessary services to help address their housing and health services. These veterans tend to lack confidence in the system to be fair in providing services to all involved individuals (Crone et al., 2021). Moreover, the African American portion of veterans tends to isolate themselves in society following problems with reintegration back into society hence lacking the support needed to help them maintain their employment and housing. These veterans tend to self-isolate as they feel unwelcome in society following discrimination.

Black Americans are overly represented in the veteran as well as the non-veteran homeless groups. Community integration remains a challenging aspect for a majority of veterans even after they have been provided with housing, and African Americans tend to experience further barriers following systemic racism. It is associated with a person’s objectivity level to be involved in vital functions such as social relations, work as well as independent self-care (Markowitz & Syverson, 2019). The African American community continues to face implicit biases, which makes it difficult for individuals to reconnect with family and society (Roberts & Rizzo, 2021). Moreover, African American individuals tend to be viewed as being more dangerous as compared to Whites, which contributes to social distancing by others impacting successful community integration.

Additionally, African American veterans face racial discrimination, especially in employment and housing, which then leads to increased poverty hence spiking homelessness. Black veterans experience racism even before discharge which is extended to post-deployment in VA benefits, hindering them from receiving the needed support to improve their quality of life after service. This enhances the risk of housing instability due to the lack of a stable income leading (Markowitz & Syverson, 2019). Therefore, black individuals are more likely to face financial disadvantages due to discrimination and racism.

As much as the military is becoming more diverse, its leadership is mostly white. Following this, black military members face more barriers to advancement due to a lack of mentorship, segregation history in the military, racism, and lack of promotion opportunities (Montgomery et al., 2020). Moreover, African Americans and Hispanics tend to be investigated more as compared to whites. This reduces the likelihood of not receiving eligibility for VA services following dishonorable discharge from service, enhancing the possibility of homelessness.

Moreover, issues in receiving VA benefits are influenced by disparities where African American individuals are more likely to have their claims regarding disability issues denied compared to other ethnic groups. The military services tend to collect ethnicity, race, and gender data concerning investigated and disciplined members following violations of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) which influences the outcomes of the case outcomes (Kessler & Gearhart, 2021). On the other hand, the Hispanic groups are underrepresented in the homeless veteran population, but a history of incarceration limits their opportunities for employment and VA support leading to the house and financial instability.

Health Conditions

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is the primary health condition affecting many homeless veterans. As identified, it is triggered by past experiences, most of which are terrifying encounters witnessed or experienced by the victims of the war. The symptoms of this health condition have been categorized into four distinct categories: cognition, mood, reactivity, and re-experiencing (Lucas et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2020). The victims are also likely to seclude themselves and get isolated from the rest of the public. According to Faria (2018), frequent flashbacks of past events deprive them of sleep hence the feeling of edge leading to unpleasant thoughts. Each of the symptoms leads to the emergence of the other making it difficult for the veterans to live normally.