Abstract

This study aims to find out the preference of consumers when made to choose between luxury brand clothing or cosmetics in their purchase and use. It focused on the preference of women aged 18 to 35 who use the internet on what to spend for more: luxury brand clothing (with possibility of an alternative for counterfeit) or cosmetics using a survey questionnaire. The objectives were concerned with the respondents’ preference on a given period. It used purposive sampling of female internet users to gauge their spending over a limited period of time on cosmetics and luxury brand clothing (or counterfeit).

This paper shall use primary and secondary data. The primary data consists of surveys on 100 females, 18-35 years old who are active internet users. A set of questionnaire was sent to them with close-ended questions and choices of answers. The secondary data focuses on published and previous literatures and studies with regards to luxury brand, fashion marketing, strategies, cosmetics, and even counterfeit products.

The findings of this study suggests that the majority of the respondents preferred to spend more on clothing, although luxury brand clothing preference was notable only to a minority of the respondents. While there are those who have also spent some amount for cosmetics, preference for clothing was more evident. However, it was noted that counterfeit products have an effect on the purchase decision of surveyed consumers.

Introduction

Fashion and the way individuals look have become a basic and important factor in their existence. While individuals find ways to improve and enhance the way they look basically through the necessary use of clothing previously understood for basic protection, today, clothing has emerged as an immediate expression of the personality as well as other aspects about an individual. This has resulted into the boom of the fashion industry which now has unprecedented scope and no sign of limitation.

On the other hand, cosmetology and the use of cosmetics reigned in so much research and marketing considerations as the quest for physical excellence and improvement of looks become the trend. People of all ages, races and beliefs were not spared especially when globalisation has taken a giant step towards converging the marketplace. While traditional cosmetics had been limited to facial colour improvisations which were generally disposed off over a short or limited period of time, more forms that are semi-permanent as well as permanent cosmetics have emerged.

There is consistent evidence in research that what is beautiful is good as well as physically attractive is valued positively. It follows that good-looking people are associated with desirable personality traits and are also treated more favourably by others (Eagly, Ashmore, Makhijani & Longo, 1991). These suggestions were perceived by the majority as generally acceptable and that both manufacturers in the clothing and cosmetics industries only have to agree. Marketers likewise have taken various methods and strategies to maximise gains in line with physical appearance and beauty.

Both luxury brand clothing and use of cosmetics serve as factors to achieve goals that may include improved physical looks, higher self-esteem, as well as expression of individualism or lifestyle. It has never been clear, however, whether consumers would prefer to use one medium over the other to achieve the goals mentioned. Fashion and clothing have been extensively accepted as a lifestyle and personal expression. There has been minimal information on how consumers may prefer one over the other or that clothing and cosmetics fare against one another amongst consumers.

This study shall focus on gaining information among respondents and presumably consumers about their preference on spending, expenditure, or choice when made to pick between cosmetics or luxury brand clothing. It is, however, clearly defined and limited in this study that cosmetics may be luxurious brands but that luxurious brands shall be indicating fashion or clothing only.

Another consideration of this study, is the extent of influence counterfeit clothing has on cosmetics and luxury brand clothing consumption. Counterfeit have been in existence for quite some time but it has never been as lucrative and destructive to legitimate brands as today. Globalisation has brought forth a worldwide exchange and trickling down of fashion from one point to another previously in a manner of time and decades. Today, trickling down of fashion from the purveyors, that is a strata of society looked up on, to the masses have been described as a matter of minutes. It is of note that counterfeit also had the same path as luxury brands and affects negatively legitimate design and labels.

This study will determine among 18-35 year old females whether they prefer to spend on luxury brand clothing (counterfeit) or will rather buy and use cosmetics over a period of time. Result would provide an insight to the ever tightening competition in the consumer market with regards to physical appearance and lifestyle expression.

Aim of the Study

This study will try to investigate if consumer preferences are different when making purchase decisions of luxury brands within the fashion and cosmetics industries. Likewise, it will also consider the impact of fake luxury items on the decision making process.

Objectives

The objectives of this study are:

- To establish a definition of luxury goods

- To investigate the purchase decision process when buying luxury brands

- To assess if there are differences on consumer behavior when purchasing clothing versus cosmetics

- To explore consumer willingness to buy and use fake articles

Research Questions

This study used the following guide questions to reach its objectives:

- What is luxury brand?

- What are cosmetics?

- What is counterfeit?

- What are the trends in luxury fashion?

- What are the strategies used in marketing cosmetics or luxury fashion?

- What are the perceived customer attitudes when it comes to purchase on fashion or cosmetics?

Relevance of the Study

The resulting information to be gained in this study will provide an insight among marketers within the fashion and cosmetics industries as to the existence or absence of competition among them when it comes to consumer decision.

The clothing and cosmetics industries have been hand-in-hand in most or the majority of market positioning, target, communications, and even branding and association. It is therefore necessary to obtain an insight if there exists any form of competition between luxury fashion clothing and cosmetics in order to carefully address marketing and communications concerns. Likewise, this research will also provide decision-makers information about the impact counterfeit may have on luxury brand clothing, as well as its impact on the purchasing decision of consumers on clothing and cosmetics.

Review of Related Literature

Introduction

Lifestyle is a continuing way of how individuals or groups may do and express their preferences generally through consumption and activities. In defining their preferences, a certain lifestyle of consumers is expressed. The purpose of this research is to provide an overview on how female consumers express their lifestyle through preference of luxury brand clothing over cosmetics consumption.

Through published studies and earlier researches, this paper shall proceed to define key terms fashion, clothing, cosmetics and luxury, counterfeit, as well as trends in marketing, strategies to get to the customer, branding, positioning among others. These are all tools and ways to which the objective to gather the preference of the consumer when made to choose between luxury brand clothing, cosmetics, or even counterfeit, will be achieved.

Brands

Keller (1998) suggested that successful brands depend upon the creation of high levels of brand awareness as well as distinctive and positive brand images. Brand image is the role of brand names and its aspects serve as cues that provide perception of product attributes, benefits, affect and overall quality (Cote, Leong and Scmitt, 2003). It facilitates recall and inference of previously learned brand attributes or associations used by consumers to evaluate a product under consideration or in the consumers’ choice. Brand cues such as name, logo, packaging design among other readily perceived attributes usually provides basis for discrimination among consumers, but memory in associating this brand cues also come from prior learning of product quality (Alba, Hutchinson and Lynch, 1991)

Brands & Consumers

Prior knowledge about brands result from memory traces of prior consumption experiences as well as abstraction or summary evaluations which Chattopadhyay and Alba (1988) suggest as easier to remember. Learning from direct experience can be more effective as compared to secondary sources or indirect learning from advertising (Wright and Lynch, 1995).

Discrimination, however, between brands as perceived by consumers has been considered difficult even in cases where there exist substantial differences between competing brands (Hoch and Deighton, 1989). Consumers usually buy and use products sequentially and not simultaneously which does allow effective comparison and contrast for alternatives. Likewise, significant delays between consumption experiences and subsequent purchase occasions impede retrieval for brand quality so that confusion may be present in consideration of brand experiences.

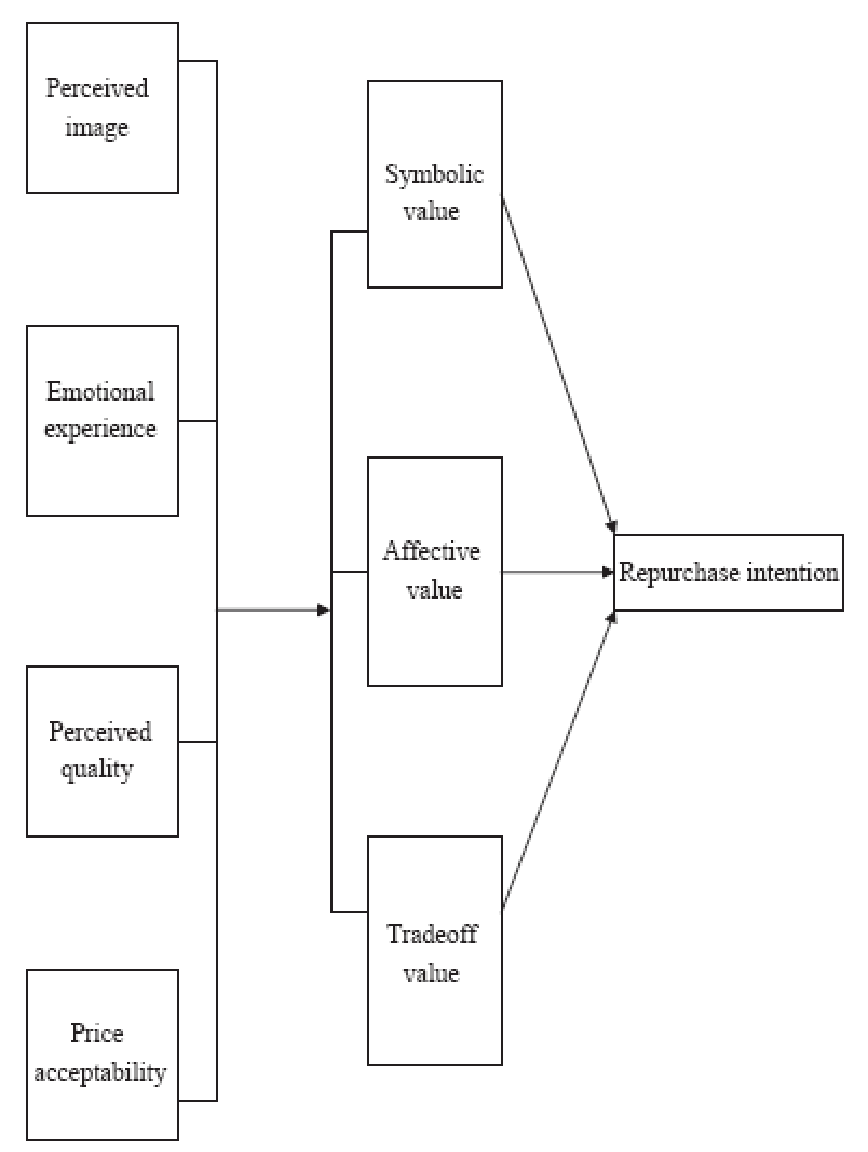

Tsai (2005) suggested that in consideration of repurchase intention, brand dimensions of perceived image, emotional experience, perceived quality and price acceptability as well as symbolic value, affective value and trade off value are generally considered. These are all considered in this research as there seem to be always a pattern on the choice of consumers with regards to purchase decision from first buying experience to a subsequent purchase for a certain product, brand or label.

Dunning (2007) provided that there is the role of self-image motives in consumer behaviour and that consumers are dynamic, motivated agents who evaluate themselves and the world around them consistent with a set of sacrosanct beliefs and self-motives. Belk (1998) supported that these beliefs and motives lead to consumer behaviours with the tendency to think of possessions as extension of the self. However, Dunning (2007) suggested people are aware of their choices and that self-beliefs reflect these choices.

Cosmetics

Cosmetics are generally understood as substances used to enhance, maintain an attractive appearance, or protect the human appearance or odour of the skin widely used all over the world today. These products include skin-care creams, lotions, powders, perfumes, lipsticks, fingernail and toenail polishes, eye and facial makeup, permanent waves, hair colours, hair sprays and gels, deodorants, baby products, bath oils, bubble baths, bath salts, butters and many other types of products. One kind of cosmetics is called “make-up” generally referring to coloured products that alter the individual’s appearance. Manufacturers today distinguish cosmetics as either decorative cosmetics or care cosmetics (Lewis, 2007).

It is estimated that the worldwide annual expenditures for cosmetics is about £9.5 billion (Mayell, 2004). The oldest and the largest of the major firms engaged in cosmetology is L’Oréal founded by Eugene Schueller in 1909 as the French Harmless Hair Colouring Company. According to Lewis (2007) the market for cosmetics was developed in the United States of America during the 1910s by Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubinstein, and Max Factor. These organisations were later expanded when Revlon was established just before World War II and Estée Lauder after the war.

The different products under cosmetics include lip improvement products lipstick, lip gloss, lip liner, lip plumper, lip balm, lip lustre, lip conditioner and lip boosters; foundations which is used to colour the face and conceal flaws to produce a desired impression, usually a mood like sporty or healthy, or even gloom that come in liquid, cream, powder or mousse form, and powder, or face illuminator used to set the foundation with a matte finish; rouge, blush or blusher, cheek stain used to colour the cheeks and emphasize the cheekbones and may be in powder, cream and gel forms; bronzer, used to create a more tanned or sun-kissed look; mascara and lash extender, lash conditioner used to enhance the eyelashes that comes in different colours and may be even waterproof; eye liner and eye shadow, eye shimmer and glitter eye pencils as well as different colour pencils that provide colour and emphasize the eyelids such as larger eyes as a sign of youth; eyebrow pencils, creams, waxes, gels and powders are used to fill in and define the brows; nail polish, used to colour the fingernails and toenails; concealer, usually a powder or a thick opaque cream used to cover pimples, various spots and inconsistencies in the skin; skin care products such as creams and lotions to moisturize the face and body, sunscreens to protect the skin from damaging UV radiation, and treatment products to repair or hide skin imperfections such as acne, wrinkles, dark circles under eyes (Lewis, 2007), and many other forms and categories that come out in succession in the market today.

Cosmetics are also be categorised by the form of the product and the area for application. These may be liquid or cream emulsions, powders, both pressed and loose, dispersions, and anhydrous creams or sticks (Lewis, 2007).

The recent years, however have seen not only the increase of over-the-counter cosmetic products as market for prescription or surgical cosmetic procedures boomed. Product and services range from temporary enhancements, such as cosmetic coloured contact lenses, tattoos, to major cosmetic surgery on nose, lips, dental, and other skin enhancement procedures. Techniques such as micro-dermabrasion and physical or chemical peels, remove the oldest, top layers of skin cells allowing younger layers of skin to appear, providing a more plump, youthful, and softer skin. Tattooing as a permanent application of pigments has also became a popular option (Lewis, 2007).

Cash (1985) suggested in a study that examined individual differences in a largely sex-specific facet of grooming, facial cosmetics use among 75 female college students, higher-quantity users were found to be more sex-typed on bipolar but not unipolar sex-role identity, somewhat more profeminist in attitudes, and less external in locus of control for achievement success. The study used the Cash Cosmetics Use Inventory, which assesses the quantity and the situational-dispositional pattern of cosmetics use. The subjects completed personality measures of sex-role identity, sex-role attitudes, social self-esteem, and locus of control. The study found that women who were more situationally variable in their pattern of use did not differ in sex-role identity but were more liberal in sex-role attitudes and more internal vis-a-vis affiliative outcomes.

Workman and Johnson (1991, p 63) found in another study on a single factor experiment with three levels of cosmetics from heavy, moderate to none, “85 undergraduate females viewed one of three coloured photographs of a professional model wearing either heavy, moderate, or no cosmetics and indicated impressions of her attractiveness, femininity, personal temperament, personality, and morality by checking 7-point Likert-type scales.” The study also revealed no significant difference on impressions of personal temperament or personality traits based on cosmetics use concluding that cosmetics use significantly affect impressions of attractiveness, femininity, and morality.

As early as 1952, it has been noted that cosmetics use result in negative impressions (McKeachie). Young women that used lipsticks were perceived by young male students as more frivolous, less talkative, more anxious, less conscientious, and more interested in the opposite gender as compared to young women without lipstick. This, nevertheless, has been changed over time as 30 years later, cosmetics provided positive effects as those wearing facial make-up had been rated as clean, tidy, feminine, physically attractive and mature looking. On the personality side, they were also perceived as more secure, sociable, interesting, poised, confident, organised and popular. The positive perception was suggested to be attributed to physical appearance of the person (Graham and Jouhar, 1981).

Use of cosmetics throughout the years, however, provided two opposing impacts both on user and viewer. Cash et al (1989) a change in perceived physical appearance in the context of self-applied cosmetics was noted as males judged women from photographs as more physically attractive. Women also believe to be more attractive when wearing their customary cosmetics. However, increased attractiveness has been found to have a negative impact on perceived personality in cases where heavy make-up is used. Johnson and Lewis’ 1988 study found that wearing even moderate make-up triggered negative opinions as being less moral and less romantic. However, it was also suggested that cosmetics use has a different meaning for different social or age groups (Huguet, Croizet and Richetin, 2004).

The modern beauty industry, however, emerged with the diffusion of personal hygiene care and beauty ideals as globalisation also diffused distribution channels and ways of purchasing among consumers.

Luxury Fashion

It is recognised that the total luxury market is growing to US$2 trillion by 2010. However, the market is still basically controlled by some 35 companies from Europe and the US (60%) led by brands Giorgio Armani, Gucci, Versace and Christian Dior (Just Style, 2006). Luxury fashion represents about 5 percent of the total luxury market translating to about US$50 billion led by LVMH, Gucci group and Christian Dior Couture (Just Style, 2006).

The UK clothing and fashion industry remain as one of the more palatable as the market maintains some £32 billion in 2002 alone. LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton posted a 2005 revenue rise to €13.90 or £9.57 billion from the previous year’s €12.48. Next, in September 2006, reported as first half pre-tax profits of £1.519 billion, 45 percent coming online. Gucci, under the Paris-based PPR SA that also houses Yves Saint Laurent, Fnac and Surcouf, is included in the report of PPR SA with a 2006 July-September revenue of €4.26 billion or $5.35 billion (AP, 2006).

British, UK or London fashion have always been set apart despite the forces of non-UK brands, specifically European or American, and segmentation has actually been categorised as: McFashion, UK or London style, international superbrands, and the micro markets (Priest, 2005). Coined by Lee (2003) after the McDonald marketing phenomenon of uniformity and predictability, McFashion has been classified as disposable, quick fix international fashion, trendy, and affordable by the mass market.

Other qualities of McFashion may include star qualities that shine and busts in a short period, or those which fill high street cheap chic stores working to formulas. These had been described as the speedy trickle down version of high couture exemplified by celebrities that are replicated, but not exactly copied to give room for versatility, in a matter of ten minutes (Lee, 2003, and Jackson, 2006). Brands of this nature include items that are found and purchased at Gap, H & M, Zara, Marks and Spencer, Arcadia group, Asda, Tesco, Sainsbury, Primark and New Look (Priest, 2005).

International superbrands include designer brands that are familiar in most major cities of the world that include Giorgio Armani, Yves Saint Laurent, Gucci, Guess, Burberry, Louis Vuitton, and Veneta Bottega, Chanel, among others and are at the opposite side of the polarised UK market. As couture is the word, it has been suggested to be incorporated with designer label (Priest, 2005) with the message that the label is critical, super-luxury, rarity and quality. Despite its characteristics, these designer labels remain big business with high stakes as influenced by class, film and music stars, sports personalities and everything glamour. Driven by the media circus, couture and ready-to-wear shows, international houses acknowledge of limited loyal customers, barely 200 with majority of sales as wedding dresses (Priest, 2005).

It has been reported that UK men and women spent £1.4 billion on these items in 2002 yet its value kept rising up to 40 percent with prices at premium. Women accounted for 57 percent of purchase. Interestingly, rarity on designer labels is slowly if not yet phased out as Tim Jackson (2002) from the London College of fashion quoted foremost names in fashion superlabels Tom Ford of PPR acknowledging globalisation as inevitable, John Marc Simon of Comite Colbert and Daniel Triboulliard specify China, Taiwan and Korea as the major destinations of the majority of luxury labels.

In these instances, acceleration of new wealth in new markets as well as the global fusion of what people and consumers watch on their movies, television and media emerged as the driving forces as growth is the main target of all major designer houses. Likewise, higher level of taste, education and worldliness as a result of education, travel and growing sophistication are the other forces that define new middle market customers that are ready to pay for premium, well-designed well-engineered and well-crafted good (Silversteine and Fiske, 2003).

Nevertheless, in the UK and London scene, fashion is still considered extraordinarily rich: a creative mix distinctively UK since the 1960s called “Swinging London” or “Cool Brittania” and other marketing slogans. UK’s design school products, acknowledged at around 3000 annually add up global influence in the fashion sense as most are not exclusive designers but design technologists, fashion buyers and purchasing agents, stylists, fashion journalists, pattern cutters, publicity communications specialists and a broad range of fashion and media-related jobs (Priest, 2005).

While others may start out new labels of their own, work on a freelance basis, others have tied up with merchants to go international or promote their own brands such as the case for Stella McCartney, Katharine Hamnett, John Rocha, Betty Jackson, Alexander McQueen, and Paul Smith (Priest, 2005).

There are also those that maintained low profile with constant and steady clientele, remained small, and can only be found in creative or trendy areas of cities in the UK rejecting commodisation of fashion. These designers and their outlets remained alternatives if not the constant drivers of style and unique creations as supported by a group of creative friends, journalists and those in-the-know. In fact, although this phenomenon, recognised to be around for forty years now, have shown local presence in most major cities but maybe falsely credited to be of London in origin (Priest 2005) as other cities, mirrored through media, are perceived with their own versions.

Priest (2005) further categorised London or UK fashion into another “micro markets’ with similarities to UK or London style fashion although placed in a bracket of “hedonistic, self-focused baby boomers, and they have forsaken the trappings of retirement for clubbing, hiking and pleasure seeking.” This segment is further described to react against brands and branding although influenced by brand values, preferring to be their own stylists as may be the result of education encouraging personal views and exposure, aim for personal gratification, style recognition, ethics and individuality (Priest, 2005).

This group has been recognised as mood consumers heavily influenced by the increased consciousness on health, well-being and spirituality, recognition of quality and craftsmanship, and the so-called “added value” or products that go well-beyond purchase and wearing.

Luxury Fashion Trends in the UK

With the rise of global marketing pushed harder by the broadband internet connection, mobility and growing economies outside the western sphere (Europe, Canada and the United States), various fashion and clothing trends that have been identified include the threat of low-priced new players against established fashion brands, the diffusion of established western markets, the global expansion of luxury brand consumers from an elite group to mass consumers, and the continued mobility of the fashion trendsetting elite beyond the clout of movie, recording and television celebrities.

Being able to identify signature designer details from precious metal on a handbag, lush fabric of a dress, or sole of a shoe without having to flaunt wearing and owning them has become the trend. “Stealth wealth” comes with the premise that if one is “truly among the fashion elite you don’t need labels or logos to showcase your style and wealth. The new mantra is: ‘If you’ve got it – don’t flaunt it,’” Jackson (2006) reported on luxury fashion trends.

Counterfeit

Counterfeit version of luxury brands and even the accessibility of these designer logos to the new rich masses from Korea, China to India, have made religious western fashionistas hide their designer looks from the mainstream who wants to scream about wearing them. Asia has accounted as much as half of the $80 billion global luxe industry and this did not only make designer labels accessible but are easily counterfeited as “genuine fakes” (Chadha and Husband, 2006) decreasing its appeal to trendsetters. Yale University professor Ravi Dhar accounts it as “It’s the same thing at play here […] It’s showing off by not showing off,” (qtd., Jackson, 2006).

This trend may have been a take-off from not-readily identifiable uber-premium designers like Bottega Veneta whose styles are not as readily identifiable and easily counterfeited such as Burberry and Louis Vuitton but this understated style becomes detectable only by fellow designer loyalists considered as part of the elite (Jackson, 2006). Burberry’s reportedly started downplaying its trademark plaid when British soccer thugs called “the Chavs” started being identified with the brand’s signature plaid, making Burberry’s high end customers in the UK shun the brand as they did not want to be associated with the subculture society (Jackson, 2006).

“Dressing the part” in purse parties no longer set apart a wearer of designer labels that are either easily and constantly counterfeited or easily bought at eBay. Logo-free items with subtle labelling but well-made and classic are preferred as the celebrity-obsessed culture takes cues from awards shows and entertainment rags. Radley Cramer, director of the fashion program at Marist College in New York was quoted saying, “If you go back 200 years in history, the royals would set the fashion standard and it would take about 10 years for the trends to trickle down to the masses […] Today, celebrities are the new royalty and the trends take 10 minutes to trickle down. Therefore, the trendsetters out there are constantly reinventing themselves,” (qtd., Jackson, 2006).

Prior to 2005, Thomas (2004) already noticed and predicted trends and fads in fashion highlighting the fact that “fashion is moving so fast that we need to decode quickly the distinctive details that create a new key piece. Today, designers present a fresh catwalk idea, and within a few weeks they are horrified to find that more than one high street store is already selling the cream of their designer collection ideas.” She added that in instances like this, the higher end gets the bulk of the problem as those who desire exclusivity loses the very thing that sets them apart from those who know nothing about fashion.

Thomas (2004) emphasised that there exists logo fatigue as also acknowledged elsewhere (Klein, 2000) and that only China and Japan desire for logos in dressing. “Only chavs really wear logos,” Thomas added with the vindication that craft should be individual, personalised and customised in order to “empower the consumer with some measure of self-selection and personal designing input…”

For formality, counterfeit goods are considered reproductions that look identical to legitimate products in appearance, packaging, trademarks and labelling (Ang, Cheng, Lim and Tambyah, 2001). The difference is that counterfeits were made to deceive although several terms may be confused with counterfeit, such as pirated goods, imitation goods and grey-area goods as Prendergast, Chuen and Phau (2002) suggests that counterfeit goods are copies made and sold to deceive consumers into believing the products are authentic, pirated or “bootlegged.”

As such, consumers may purchase products with the knowledge that they are fakes. On the other hand, imitation goods are copies that are similar but not identical to the authentic items and imposter fragrances may be categorised as such as these imitate designer fragrances that sell at much lower prices. These are called knock-offs. Gray-area, meanwhile refers to goods that are genuine trademarks and are sold outside authorised distribution channels.

According to the ICC Counterfeiting intelligence Bureau (2004), counterfeit product sales reached an estimated US$376.2 billion and have cause hundreds of thousands of job loses worldwide. Green and Smith (2002) reported that companies such as Louie Vuitton, Cartier, and Gucci expend a great deal to combat counterfeiting.

Market Segmentation

This paper will also explore on market segmentation as defining the markets of both luxury brand, counterfeit and cosmetics could provide a deeper understanding on strategies applicable on the process of marketing these products.

Market segmentation, positioning and the marketing mix all play pivotal roles in consumer marketing, specially luxury fashion, and those who counterfeit them, as well as cosmetics. For enterprises, locating and targeting unique market segments is a necessity in order to become competitive in the marketplace (AMA, 2005). Creative market segmentation strategies allows a business organisation a strategic advantage over its competition as underserved niche are uncovered, and gunning marketing and financial resources into that niche (Neal, 2005). Each segment responds differently from others to the variations of marketing mix. Four basic criteria were set by Green and Tull (1978) as follows:

- That the segments must exist in the environment and not be a figment of the researcher or management’s imagination

- That the segments are repeatedly and consistently identifiable

- That the segments must be reasonably stable over time

- And that one must be able to efficiently reach these segments through specifically targeted distribution and communication initiatives.

As such a firm is expected to either adopt the mass-market strategy or a market segmentation strategy and never anything in-between (Neal, 2005). In the process, senior management is involved in the strategic decision in the effective market segmentation where alternative marketing strategies are executed in pricing, promotion, and distribution systems. Likewise, it is not enough that research and development can execute product or service variations. The whole process involves manufacturing to produce the variations, finance to report costs, profits and margins, with the marketing research able in monitoring and measuring customer response (Neal 2006).

For most firms, the practice is to develop market segments for each product category, discern current and proposed positions within each of the segments, then select its target market based on the opportunities that exists in each segment (Neal, 2005). It is also necessary that a firm sets initial forecasts of market demand before fine-tuning its marketing mix to achieve optimum results in positioning and penetration. The basis for segmenting a market may include: “Product class behaviours; Product class preferences; Product class-related attitudes; Brand selection behaviour; Brand-related attitudes; Purchasers’ attitudes toward themselves and their environment; Demographics; Geographics; and Socioeconomic status,” (Neal, 2005).

There are two methods for market segmentation:

- A priori segmentation – this grouping may result from a company tradition, recognised industrial groups or other internal or external criteria where a firm chooses to break customer groups by a generally accepted classification procedure related to variation in customer purchase or use of a product category. Samples include: “Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) groups; Geographic regions or sales territories; Basic demographic groups (e.g., sex, age, household composition); Purchase or usage groups (e.g., heavy users, light users, nonusers); VALS (SRI’s Values and Life Styles classification system); and PRIZM, or similar geodemographic classification systems,” (Neal, 2006).

- Post hoc segmentation is based on the results of research study undertaken for the purpose of market segmenting formed by aggregating buyers who respond similarly to a set of basis questions with a selected basis variables that may include: “Product attribute preferences; Values; Product purchase patterns; Product usage patterns; Benefits sought; Brand preferences; Price sensitivity; Brand loyalty; Socioeconomic status; Deal proneness; Lifestyles; Self-image; Attitudes and opinions toward one’s environment; and Dealer loyalty,” (Neal, 2005).

As market segmentation involves partitioning a large market into smaller groups, firms and business organisations in the luxury fashion and cosmetics may deal with each segment by specifically providing which is most needed by the customer in a certain segment, allowing price and product changes a reasonable range for the segment to avail. In some instance, the firm may also pursue just one segment or all of the segments with enough profitability. Appropriate segment is evaluated against the organisations own strengths weaknesses and strategic objectives (Dutka, 2006).

Two segmentation techniques are as follows:

- Perceptual Mapping – it is a tool to discover how consumers differentiate products or organisations where relations are portrayed by the relative position of points on a two-dimensional map. Distance between points indicates the degree of relationship between the variables while points that cluster reveal those which are closely related.

- Decision Tree Analysis – uses cross tabulations to examine results of a particular survey question and can be very complex in determining specific categories as analysis must identify as many practical and potential combinations. Isolation of relationships follow and is tested by a statistical method to ensure that the data conveys real insight (Dutka, 2006).

Positioning

Burberry back in 1998 had its annual profit drop from £62m to £25m that led to criticisms of Burberry as an outdated business with a zero fashion cachet. But the company made a u-turn with significant improvements in its business performance through re-positioning strategy (Moore and Birtwistle, 2004).

Positioning is considered an art of tailoring the image and presentation of a product or service to appeal to a selected or targeted market segment (Dutka, 2006) enabling marketers to draw a direct link between product attributes and specific customer needs instead of crafting a general appeal. Positioning strategies already existed for decades and is closely related to market segmentation as the process involves identification of potential customers. It is used in today’s diverse marketplace as an essential marketing tool for success. Coco Chanel was identified to have used product positioning as early as the 1920s with self-styling promotion using neutral tones of beige, sand, cream, navy and black coupled with soft fluid jersey fabrics in simple shapes (Thomas, 2004).

Product positioning reduces costs for ineffective marketing and advertising to remain competitive in the increasingly complex business environment.

In positioning, association or brand association may matter. Fashion brands gain competitive advantage with the associations they have, from the retail shop to the buyer or wearer, and in a common department store or retailer shop, through design aspects within the concession shop (Gretz, 2000). Design has been used as a key solution in providing differentiation from other concession shop products within the store. Elements include store façade, interior, décor, lighting, atmosphere, fixtures, and design of hangers. Details become necessary for brands to become highly visible (Gretz, 2000).

Concession and host retailer also develops alliance that affect the brand image of luxury fashion. From the start, manufacturers chose the appropriate retailers that must carry their brand names lest a negative association could impact to its existing and prospective consumers. Composite brand alliance was defined as an indirect form of brand extension (Park et al, 1996) while a close relationship between brands combined with the impersonal business relationship shape the interaction between brands and shaping awareness in co-branding (Uggla, 2001).

Marketing Mix

The marketing mix is an approach in crafting and implementing marketing strategies emphasising the blending of factors to obtain organisational and consumer objectives (Borden, 1964) as inspired in a James Culliton article. The target market in cosmetics, luxury fashion and even counterfeit industries, is foremost considered in blending the elements by understanding the wants and needs of the market or customer.

“When building a marketing program to fit the needs of his firm, the marketing manager has to weigh the behavioural forces and then juggle marketing elements in his mix with a keen eye on the resources with which he has to work,” (Borden, N. 1964 pg 365). Certain marketing mix is usually prepared for every product offering or each market segment which is also dependent on the organisation. McCarthy (1960) suggested the following as the most common variables in the marketing mix:

- Product is the luxury fashion brand

- Price is usually exorbitant for the masses

- Place or distribution is through retail shops that is frequented by trendsetters and the fashion elite

- Promotion is the communication between the organisation’s product to its target consumers using marketing strategies and advertisements.

Marketing Luxury Fashion

There are a variety of ways to build a luxury fashion brand but the consumer play a major role in its success or failure. McRobbie (1998) delineated two pillars of the British fashion as the art school establishments and fashion media represented by women’s fashion magazines. So that the thousands of fashion design graduates of London have two ways to go: build their own names or tie-up with established fashion houses. In this instance, the consumer was not included in the picture as she noted how many have gone bust after a year or two. But trends identified as the British or UK fashion which may be categorised in this instance as “independent” by this researcher taking from the so-called “indie” label of the recording industry, as well as the micro market (Priest, 2005) created a niche for small and struggling designers with the value only superbrands could muster and equal.

Luxury fashion has always been identified with established brands, as most talented names also start out with established brands prior to branching out on their own, or until a designer name that is about to make it are bought by established fashion houses. But brands notwithstanding, certain qualities are always associated with luxury brands: craftsmanship, comfort, durability, and style. Other qualities may depend on place or country of origin, material, and subliminal messages that are part of the branding as Kotler (1994) defined:

- Attributes – such as expensive, exclusive, well-made, modern, classic, durable or comfortable

- Benefits – which include functional as the garments may be worn for years, and styled to last for several seasons, as well as emotional benefits of the feeling of wealth and security, affluence, importance and admiration, pleasure and high self-esteem

- Values – such as classic, quality, artistic or traditional

- Culture – as that of English tradition, the monarchy, class system and pride in history and craftsmanship, or the Italian style and originality of design.

- Personality – of which a brand projects age, maturity, occupation, wealth, social status, or aristocracy

- Use – conveys profession, age, career or position, social status, and even personal or professional achievement.

This illustrates that luxury fashion brand is more than a name, and has achieved the status of an identifier where individuals wearing or preferring certain brands or style develop a bond which may not be achieved in any other way. As clothes were acknowledged as a form of non-verbal communication since it has become so visible component of the individual’s daily device, Kaiser (1990) suggested that it helps individuals organise and make sense of his or her social experiences.

In establishing luxury brands especially for new players, repurchase intention marks an apparent motivational state of consumers to repeat a buying behaviour and that there is a designated consequence of perceived value (Chang and Wildt, 1994). This led to brand marketing and communication efforts to enhance perceptions of brand purchase value to elicit favourable repurchase behaviour (Munger and Grewal, 2001).

While it was postulated that the economic value of functionality and substitutability was once considered as the prime model for trade-off purchase (Dodds, Monroe and Grewal, 1991), other marketing researchers (Fournier, 1991, Belk, 1995) argued that contemporary consumer behaviour should be closely associated with post-modernism as a socio-cultural phenomenon, or individuals consuming is not for basic needs but in pursuit of self identity, social groups and culture or even subculture. Further, it links consumer purchase behaviour to symbolic meanings of products in relation to the self, social and cultural context where individual consumers exist.

Nevertheless, emotion is still considered as a factor in the stream of consumer behaviour (Elliott, 1997 and Shawarz, 2000) putting emotion or affect ahead of cognition as a main factor in consumer behaviour. That consumers have a general propensity to seek out affective situations, enjoy emotional stimuli, and exhibit a preference to use emotion in interacting. A holistic approach was also proposed for the investigation of brand purchase value (Mano and Oliver, 1993 and Schmitt, 1999) while others link it to a multi-dimensional construct affected by symbolic, emotional and cognitive factors ( Sweney, Sotar and Lester, 1996).

Sai (2005) suggested the above structure to validate consumer purchase behaviour. It is to be noted that people buy luxury products because they cost more and does not necessarily proven as better in aspects than the cheaper brands (Dubois and Duquesne, 1993) but Silverstein and Fiske (2003) argued that luxury brands are used to enhance one’s social status and that even middle class attain the perception of prosperity, individual wealth as well as differentiation from others.

Summary

Basing on the present literature, many factors, strategies and conflicts are considered by marketers of cosmetics and luxury brand clothing, and even counterfeit providers, when it comes to dealing with consumers and market positioning. Consumers are constantly seeking ways to express their lifestyle through preferences and this is highlighted most obviously by their physical appearance, directly impacted by clothing and cosmetics.

However, it is of note that while both cosmetics and clothing are defined self-expression of lifestyle as well as used to providing a positive image on a social aspect, they are not necessarily given an equal ranking on importance. It is of note that clothing provides a basic purpose while cosmetics provides complementary one as maintenance or enhancement of physical appearance. It seemed that while clothing provide and define a physical appearance, cosmetics add up or improve what already exists.

This paper shall proceed to determine consumer decision when faced to choose between cosmetics and luxury brand clothing, in the presence of counterfeit.

Methodology

This study used survey method question on a purposive sampling of female internet users aged 18 to 35. The method hoped to provide a clear distinction on the preference of the respondents in order to achieve the objectives of this study. A list of electronic mail addresses were purchased from vendors. The list specifically asked for are females at age group 18 to 35. 200 e-mail addresses was provided of which originally sent an emailed inquiry prior to sending out the questionnaire. The original target quantity of respondents was 200, but due to limited resources and time, a total of 100 respondents who were able to finish and submit their answers properly were considered the final. Careful consideration as to the research method used was given in order to satisfy research objectives (Saunders et al, 2000).

Since permission was sought to each participant prior to sending out the questionnaire, and since the participants are considered matured at the age given, sufficient ethical consideration had been carefully applied in this research.

Data was gathered through collection of the respondents’ feedback or answers. These were tabulated as soon as it was deemed sufficient, or that all questions were properly answered in the given limited choices. Those which did not meet the criteria — incomplete answer to questions — were removed from the final list.

Research Philosophy

This section will discuss the research plan in details including the research philosophy, the research approach and research strategies used. Saunders et al. (2003) defined the research process ‘onion’, consisting of five different layers. This study shall provide a mix of research strategies to obtain its objectives.

The research philosophy may be framed within an interpretivistic or phenomenology philosophy, exploring, “The subjective meanings motivating people’s actions,” (Saunders et al 2003: 84). Inductive reasoning applies to situations where specific observations or measurements are made towards developing broader conclusions, generalizations and theories (Saunders et al. 2003, pp.87-88). An inductive research approach is considered the most appropriate for an interpretivistic research philosophy.

Therefore, this research will follow an inductive approach which will enable a greater understanding of the meanings humans attach to events “in which you would collect data and develop a theory as a result of your data analysis,” (Saunders et al, 2003).

In addition, an exploratory research strategy will be used in order to create a deeper understanding of consumer preferences with regards to the use of fake cosmetics as opposed to fake fashion. “Exploratory studies are a valuable means of finding out what is happening; to seek new insights; to ask questions and assess phenomena in a new light,” (Robson, 1993; 42).

Survey Method

The survey is a non-experimental, descriptive research method which is considered very useful when a researcher wants to collect data on phenomena that cannot be directly observed. Surveys are used extensively in research to assess attitudes and characteristics of a wide range of subjects, from consumer to business as well as business to business interaction, among others. In a survey, the researcher or researchers sample a population, which means that not everybody are expected to participate within a given area, locality or group of population. According to Basha and Harter (1980), “a population is any set of persons or objects that possesses at least one common characteristic. In this instance, there are at least three common characteristics of respondents, being their age categorised under an age group bracket of 18 to 35 years old, internet users, and all females.

Five preliminary steps were taken in embarking upon this research project:

- choose a topic

- review the literature

- determine the research question

- develop a hypothesis and

- operationalisation or figuring out how to accurately measure the factors this research wish to measure, that is the preference of the respondents on choosing between luxury brand clothing or cosmetics purchase and use (Meyer, 1998).

Likewise, for this research survey, two additional considerations were of prime importance: representative sampling and question design.

Cross-Sectional Survey

This study further uses the cross-sectional survey. This is used to gather information on a population at a single point in time, being started in November for the preliminary communication with the prospective respondents. However, it is to be noted that the questionnaire have indulged the subjects to recall their spending habit during the months of September, October and November. This was necessary to provide a limited time frame inclusive of the survey questionnaire. The survey ended in December, all at the same time when a minimum target of respondents was able to provide completed answers to the questionnaire sent to them.

The cross-sectional research have the data gathered from the research participants at a single point in time or during a single, relatively brief time period typically collected from multiple groups or types of people in cross-sectional research. This goal was achieved by not necessarily limiting the participants to their location, group affiliation, and other identifying status.

Purposive Sampling

Purposive sampling is a non-probability sampling strategy that targets a particular group of peoples, in this case, females aged 18 to 35 and internet users. This was chosen on the premise that the ideal population for the study is large and locating and recruiting would be very difficult due to limited resources and time, and of which purposive sampling was left as be the best option.

In this process, for almost a minimum period of fourteen (14) days, the researcher sent letters through electronic mail (e-mail) in a list of e-mail addresses obtained from legal vendors for voluntary online respondents (QuestionPro, 2007).

The list has 200 female respondent e-mail addresses with their age range limited between 18 to 35 years old. The first letter was sent inquiring whether or not the respondent would be available and willing to answer a questionnaire about their expenditure, plan and preference on purchasing luxury brand clothing and cosmetics. About 183 sent back a reply stating their willingness. Consequently, the questionnaire was sent to the 183 with a given time frame to return their answers. Only 113 were able to send back their answers but after careful consideration, only 100 respondents were considered for final presentation due to the completion of their answers as well as determination of purchase action.

Other consideration on the study was the time-frame used in the questionnaire. The last three (3) months was used covering the months from August to October as basis for determining purchase or consumption practice on the respondents as this will gauge the active consumer from the passive. The given period may also determine a sequence and pattern as well as a definitive preference.

The age group of 18 to 35 has been chosen as this group represents independent, self-sustaining and with their own income. This means that the age group decides on their own in their buying or purchase habits. The female gender was chosen as previous studies already pointed out how females are more picky or meticulous as well as conscious with what they wear or how they look over males. Likewise, online users were preferred over other group of population as these are quite easier to communicate with, speedier, and more practical to deal with. These are the underpinning rationale for choice of demographics.

Limitations of the Study

Since the respondents were only 100 females that generally represent the whole and a wide range of females using or not using luxury brand clothing and cosmetics, a bias may be obtained where consequential preference of the majority of the respondents may not represent the general majority within or beyond the age group as well as the consumer population in general.

This limitation, however, has been previously considered and may not directly affect a consensus as each of the respondents are picked randomly with only age and gender as consideration and may have come from a wide variety of peoples, cultures and classes. Another bias provided for was using the internet for respondents. It is very possible that the respondents; population would be limited to people with internet access. It was opined that “Internet users are not representative of the general population, even when matched on age, gender, etc.. This can be a serious problem, unless you are only interested in people who have Internet access.

In many business surveys this limitation might not be a problem,” (Survey System, 2008). This problem is addressed with the rationale that the internet has grown exponentially the fast few years that many class of consumers are fairly represented. Likewise, with the products concerned only on luxury fashion, cosmetics and even counterfeit, it is to be understood that the general internet users have or are regularly exposed to these products as these are now available extensively online.

Two limitations were also presented as for using questionnaire. Emailed questionnaire is structured and limited. It was not possible for the researcher to probe the respondents’ answers. (Stat Pac, Inc., 2008). However, it is to be understood that the opinion of the respondents when it comes to luxury fashion, cosmetics and even counterfeit are not necessary to reach the objectives of this study.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire used in this survey collects data on the spending habits of the 100 female respondents at the age range 18 to 35 years old. A consideration has been for the subjects to recall their last three months spending habits on cosmetics, luxury brand clothing, or even counterfeit. Likewise, the questionnaire also addressed the conscious preference of the respondents on which to spend for when pressed to choose one of the three items identified. Designing good questions proved to be much more difficult as already noted by many researchers before. But Busha and Harter (1980) provided a guideline with the following suggestions that this researcher tried to address:

- When the nature of a survey does not warrant usage, avoid slang, jargon, and technical terms.

- As much as possible, develop consistent response methods.

- Make the questions impersonal as much as possible.

- Avoid biasing later responses by the wording used in earlier questions.

- Try to sequence questions from the general to the specific.

- If closed questions are ever used, develop exhaustive and mutually exclusive response alternatives.

- Try to place questions with similar content together in the survey instrument.

- Provide questions that are as easy to answer as possible.

- In using unique and unusual terms, use clear definitions.

- An attractive questionnaire format that conveys a professional image is very acceptable.

The Questionnaire went as follows:

- Age:

- If given a choice to spend on any of the three items below, which would you give preference (please number from 1 to 3, with 1 as the most preferred purchase)

- Cosmetics

- Luxury brand clothing

- Counterfeit brand of good quality at much lower price.

- If you were to choose between luxury brand clothing and counterfeit of almost indistinguishable difference with the original, what will you choose?

- Luxury brand clothing

- Counterfeit brand of good quality at much lower price.

- When would you prefer to buy luxury brand clothing (please check one)?

- All the time I buy clothing

- At least 5 times a year

- For very important occasion only (at least 2 times a year)

- Never.

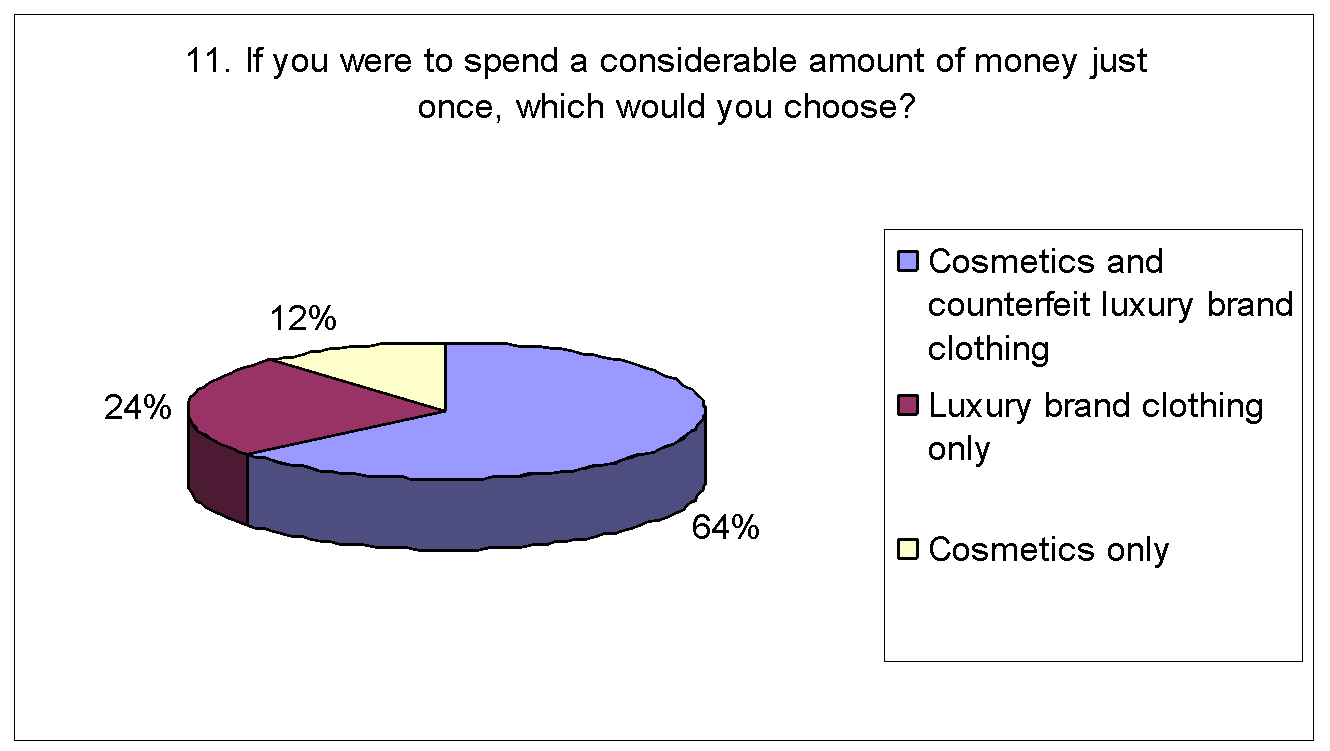

- If you were to spend a considerable amount of money just once, which would you choose?

- Cosmetics and counterfeit luxury brand clothing

- Luxury brand clothing

- Cosmetics only.

Closed-ended questions are used in the survey to determine specifically the choice answer of respondents in order to provide a solid structure to which the result may be based. In addition, closed-ended questions also are easier to analyse of which all answers are given a number or value so that a statistical interpretation can be assessed. In addition, the simplicity of closed-ended questions, make it more specific and likely to communicate similar meanings. In comparison to open-ended questions, respondents use their own words making it difficult to compare the meanings of the responses Allan and Skinner (1991).

The closed-ended question also fits it on the survey as closed-ended questions take less time of the interviewer, the participant and the researcher, and makes it a less expensive survey method. It was also suggested by Allan and Skinner (1991) that the response rate is higher with surveys that use closed-ended question as compared with those that use open-ended questions.

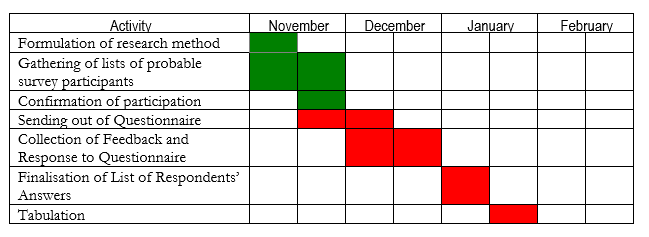

Research Time Frame and Schedule

The following Gantt chart provides an overview of the research process from the gathering of lists for probable participants until a complete survey was finalised.

Research Ethics

Research experts posed that several ethical issues must be considered when designing research that will utilize participants who are human beings as follows:

- The researcher should consider the safety of the research participant. This may be accomplished through careful consideration of the risk and benefit ratio, using all available information to make an appropriate assessment.

- The researcher must obtain informed consent from each research participant. This was obtained in writing through electronic mail in the case of this research. The participants were given enough time to reply to the email inquiry and the researcher was able to gather about 180 or so willing respondents. As the respondents were not at all pressured to reply, they were allowed opportunity to carefully consider the risks and benefits as well as to ask pertinent questions. There were those who asked if there would be other requirements except for the age and gender issues which were promptly replied by this researcher. Likewise, the researcher have emphasized that the email addresses and the answers will be kept confidential to protect the identity and privacy of the respondents.

- The researcher also enumerated how privacy and confidentiality concerns are approached. It is necessary that researchers are sensitive to not only how information is protected from unauthorized observation. They are also informed if and how the respondents may be notified of any unforeseen findings from the research that they may or may not want to know.

- The researcher also considered how adverse events will be handled with regards to the participants’ protection for privacy and their participation in the survey (Saunders et al, 2003, p. 131, and the University of Washington, 2007).

All these issues were considered prior to the dissemination of the first letter of intent among the obtained list of respondents. As the list provider was responsible in filtering the list of female participants’ email addresses, it was taken into good faith by the researcher that all respondents were females. Only their age was asked stated in the questionnaire in order to ascertain their qualification for the set age range. It was also included in the letter of intent that all participants’ addresses and responses will never be taken out public, nor would be disseminated elsewhere. The respondents email addresses would be deleted to the address book of the researcher once the completed answer sheet were emailed back.

The email addresses were promptly deleted once the final list of respondents’ answers was collected. This ensures that no more communication shall follow and the electronic communications between researcher and respondents was automatically halted. Since then, no form of contact had been made between the researcher and the respondents.

Ethics refers to “the appropriateness of your behaviour in relation to the rights of those who became the subject of your work” (Saunders et al, 2003, p. 178). The communications with respondents that closely followed Saunders et al (2003) recommendation with regards to ethical consideration are presented under Appendices.

Reliability and Validity

It is important to consider the reliability and validity of this study as there is the need to know whether the goals are being attained and that whether the measures used is consistent with what this study aims. Reliability is understood as the extent to which an experiment, test, or any measuring procedure yields the same result on repeated trials as the lack of agreement of independent observers to replicate research procedures, or the ability to use research tools and procedures that yield inconsistent measurements could lead to unsatisfactory conclusions. This will also unable to reach theories or make claims about the generalisation of the research. Reliability is critical for many parts of peoples’ lives, including manufacturing, marketing, information, amongst others (Huit, 1998).

Reliability, likewise, has been defined in terms of its application to a wide range of activities with four key types: Equivalency Reliability, Stability Reliability, Internal Consistency, and Interrater Reliability (Huit, 1998).

Validity has been defined as the degree to which a study reflects accurately or assesses the specific concept being measured or studied. Validity is concerned with the research’s success at measuring what was set out to be measured. Researchers are concerned with both external, meaning the extent to which the results of a study are generalisable or transferable (Campbell and Stanley, 1966), and internal validity referring to: the design and care with which the study was conducted; and the extent to which the researchers have taken into account alternative explanations for any causal relationships they explore (Huitt, 1998).

Summary

The whole primary research process of conducting survey and gathering the response of the respondents took place as carefully planned. All agreements between researcher and respondents were applied to ensure their privacy and protection. All data were collated and tabulated as necessary in order to provide the necessary goal of obtaining the preference of respondents with regards to purchase and use decision with luxury brand clothing, cosmetics and counterfeit.

Data Presentation

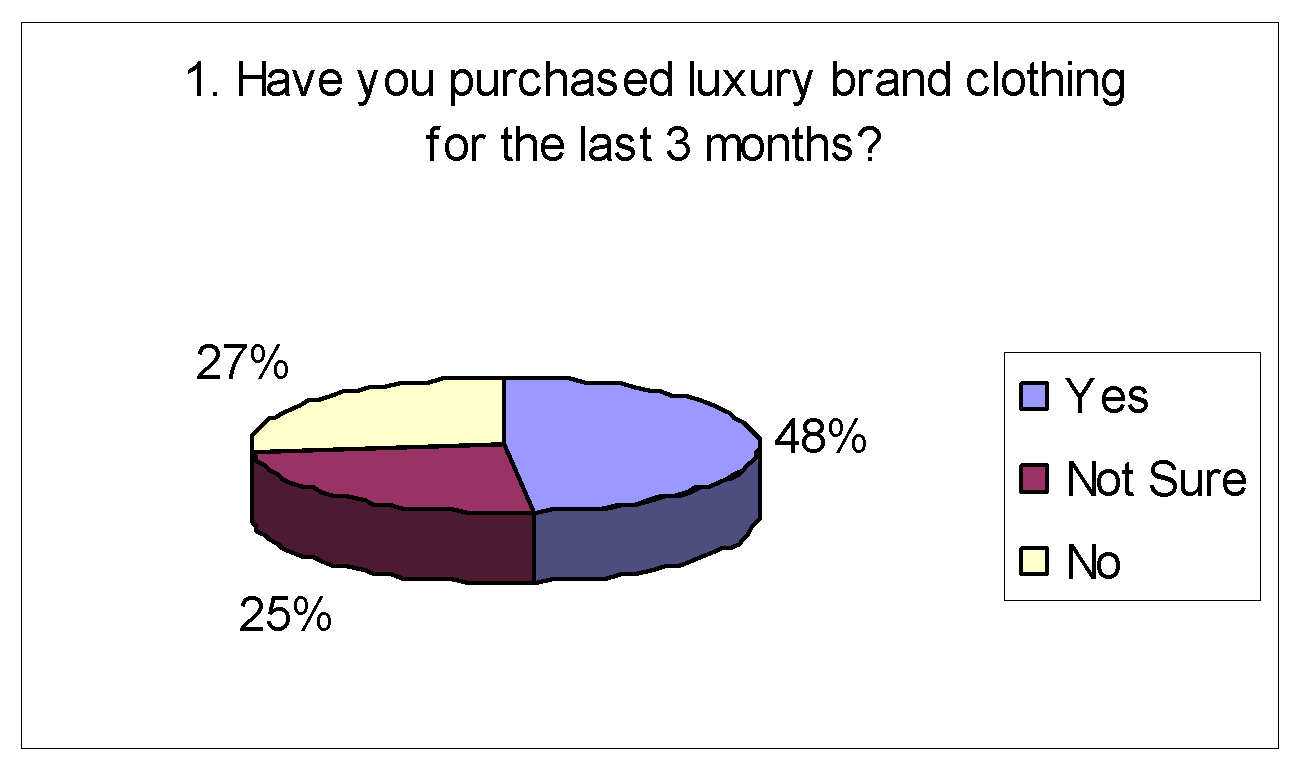

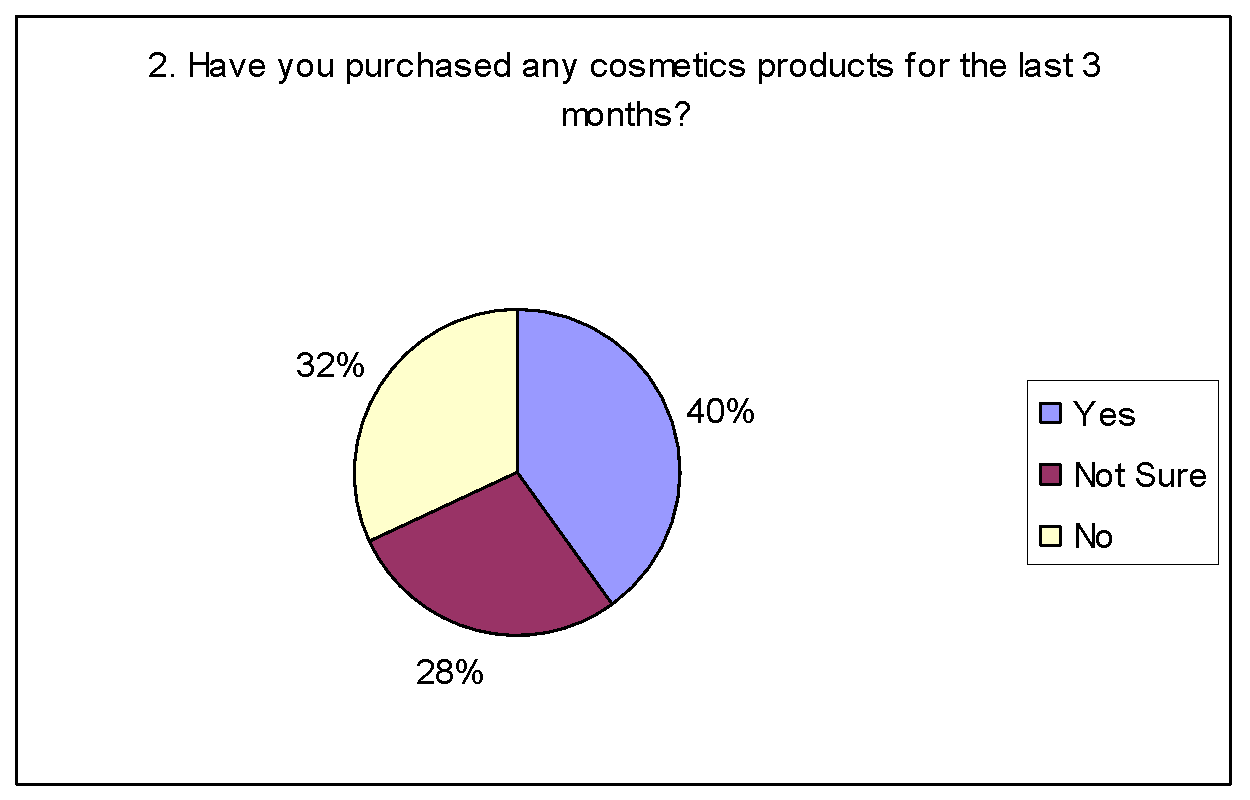

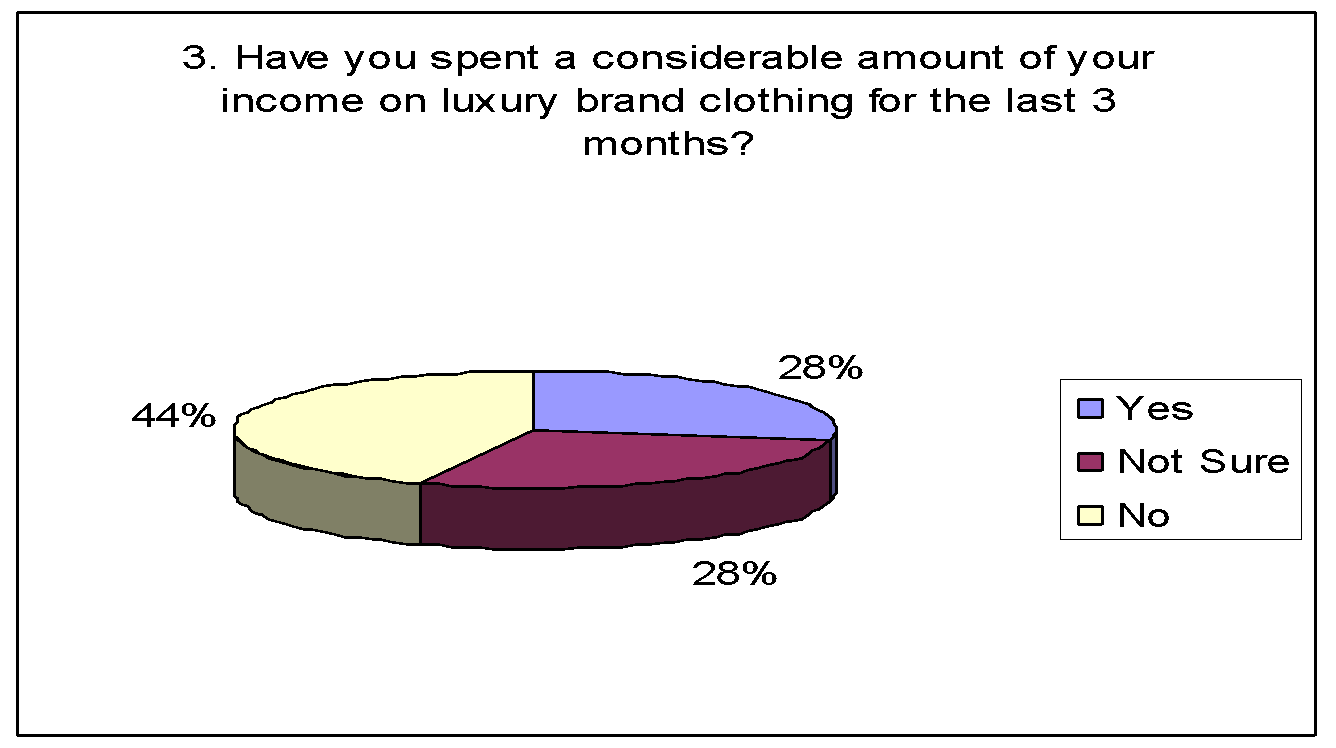

When asked whether the respondents purchased luxury brand clothing for the last 3 months, 48% said they did, while only 27% said no. As for purchase for any cosmetics products for the last 3 months, 40% said they did, while only 32% said no. As for spending a considerable amount on their income on luxury brand clothing for the same time frame, 28% said they did while 44% said they did not.

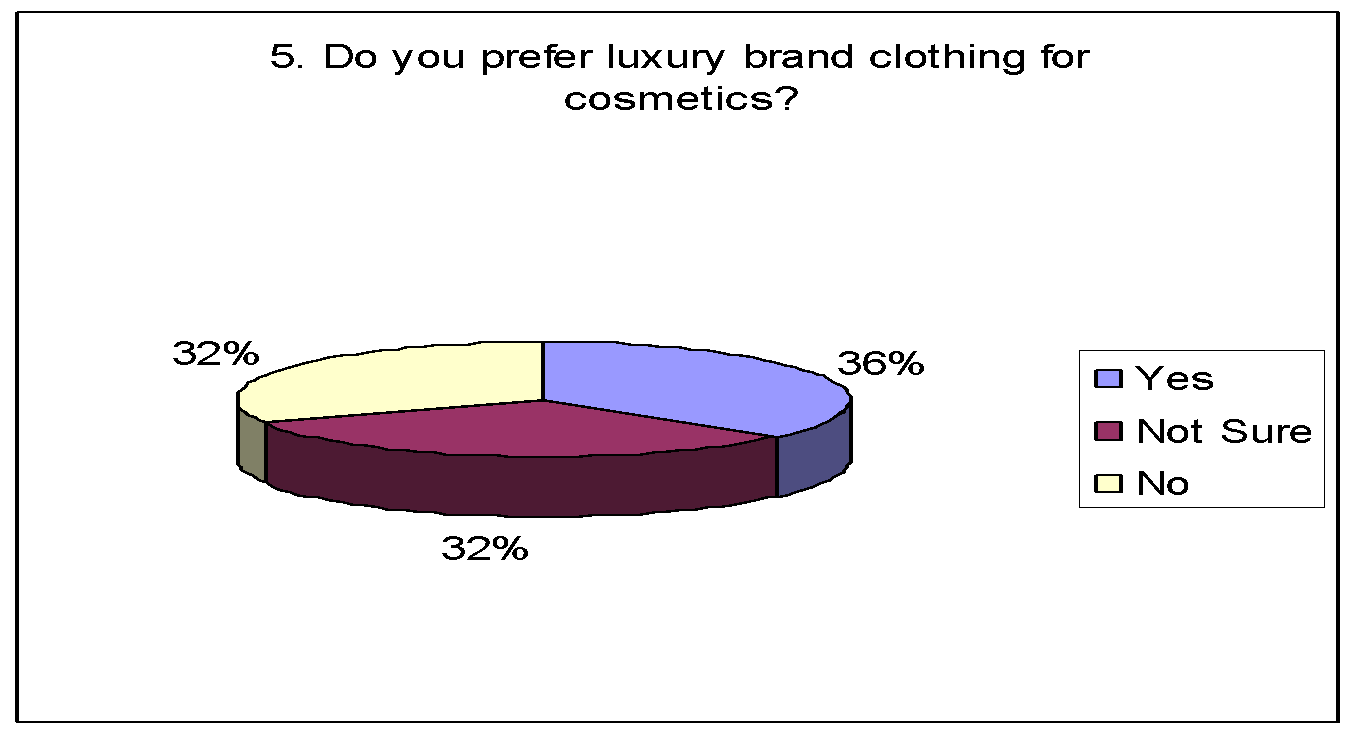

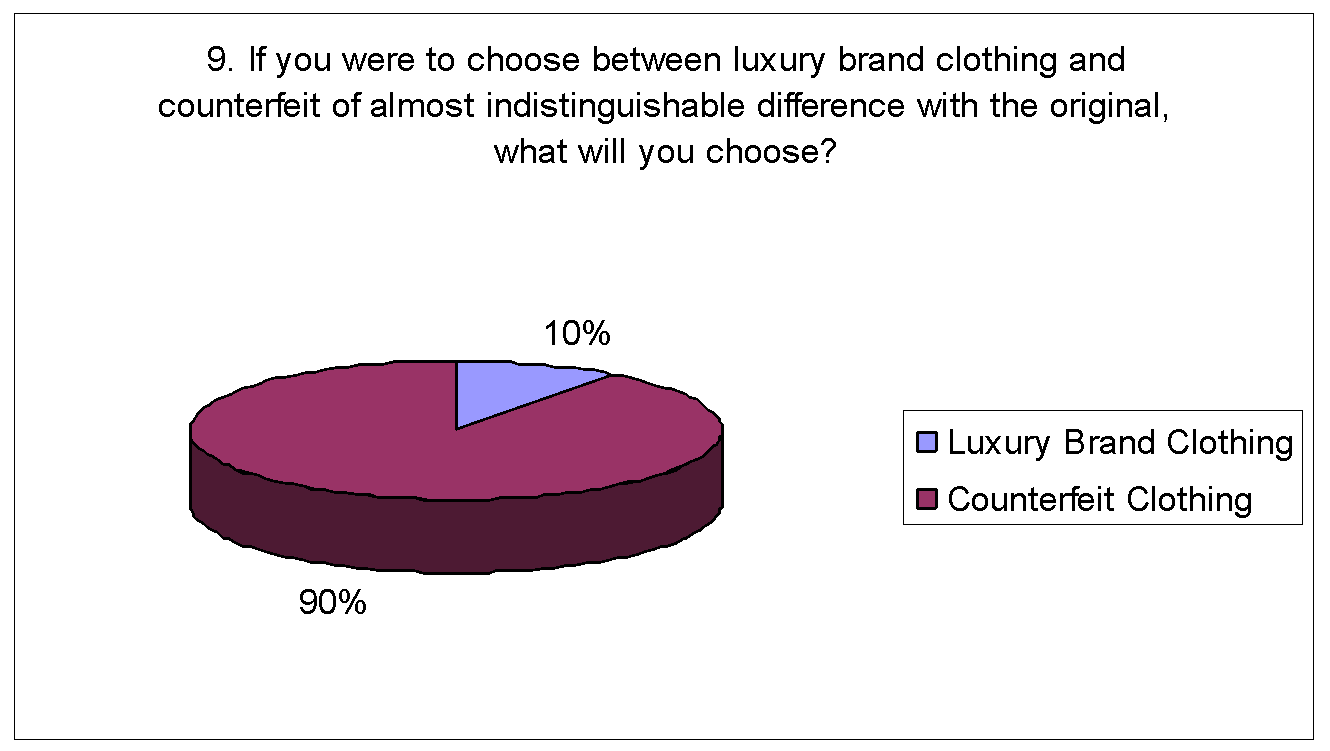

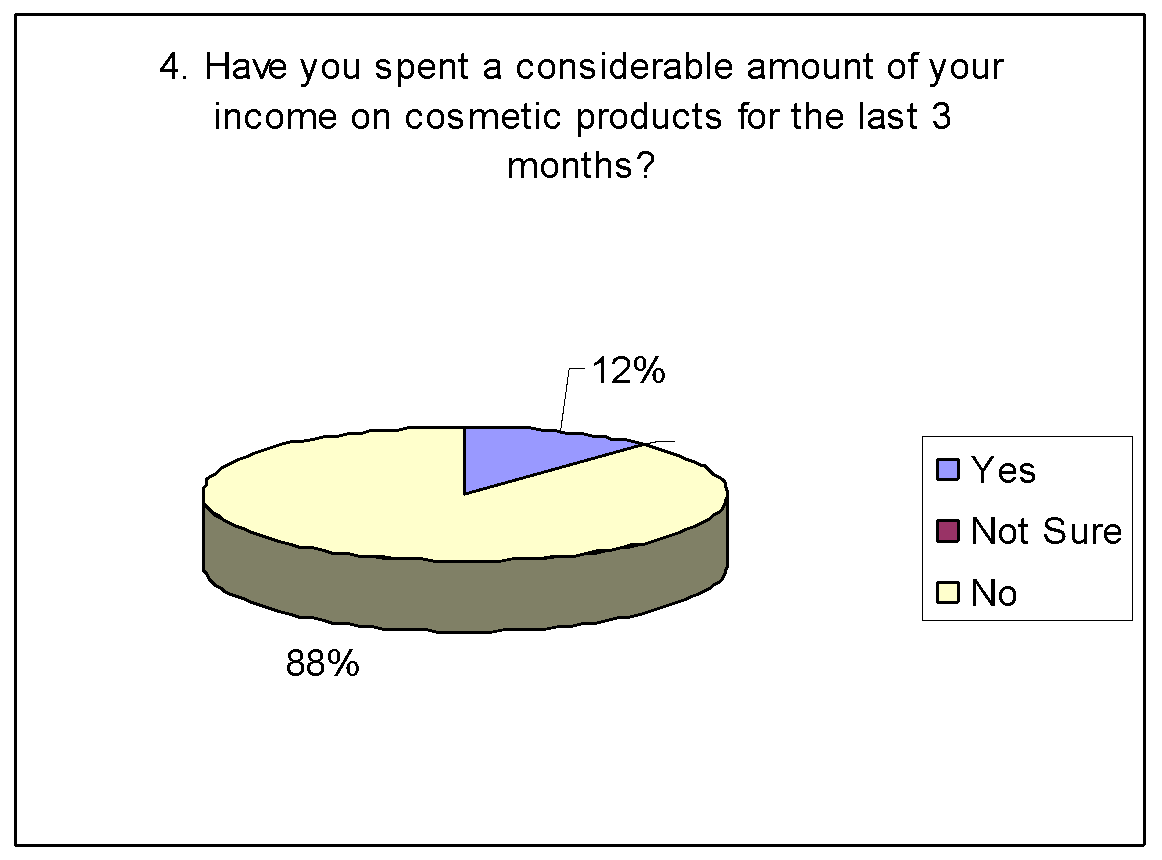

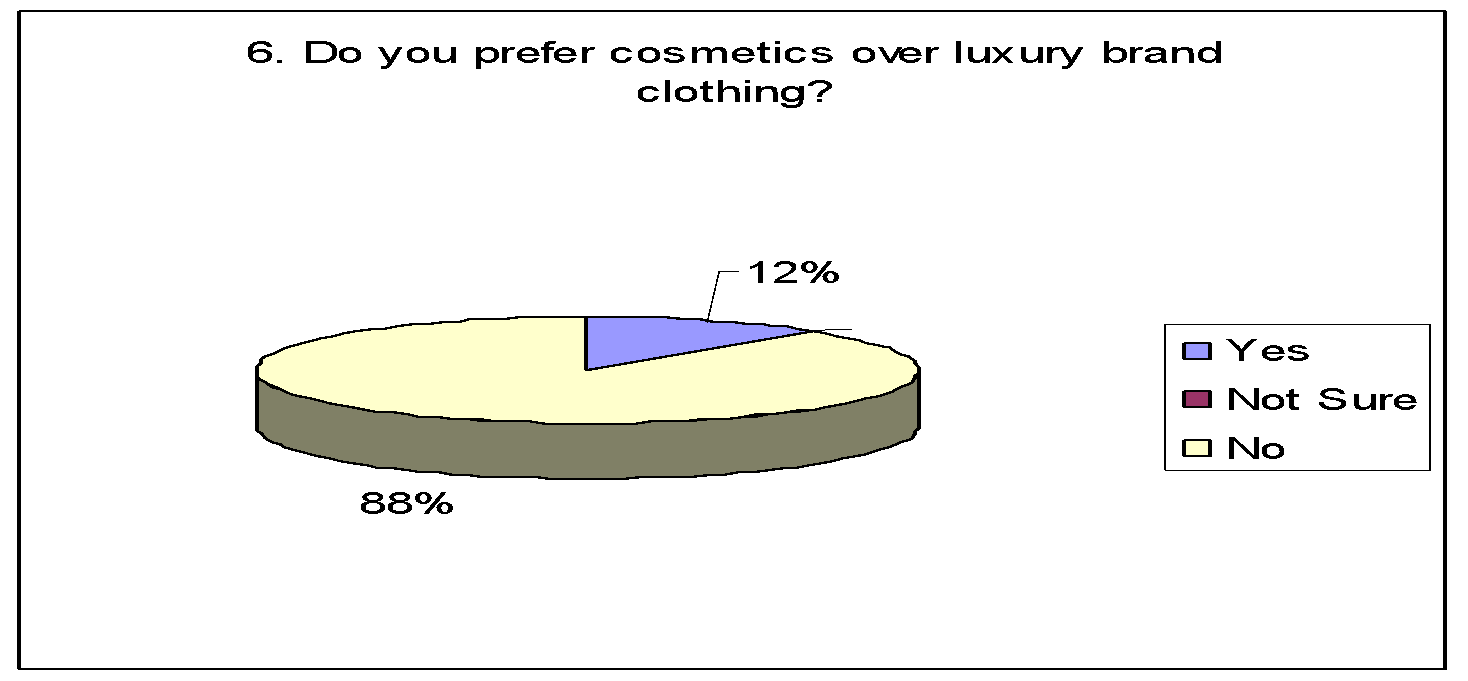

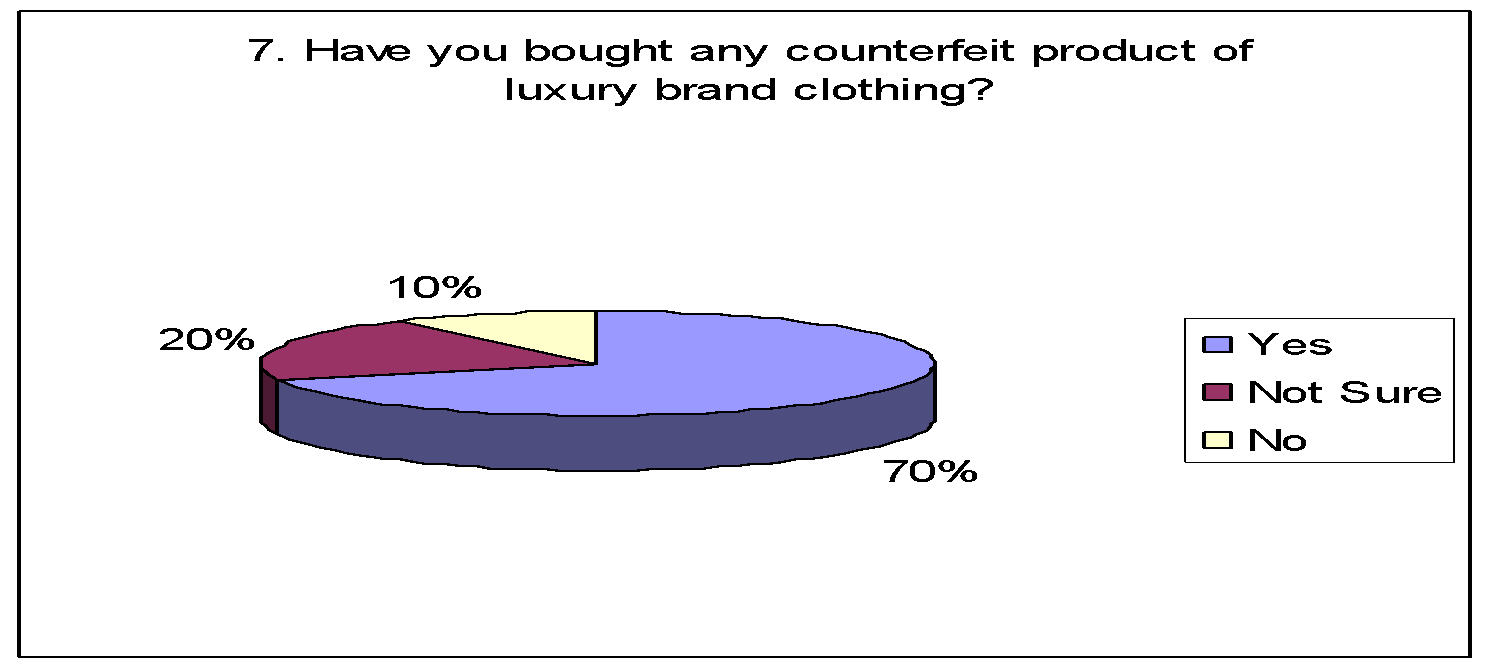

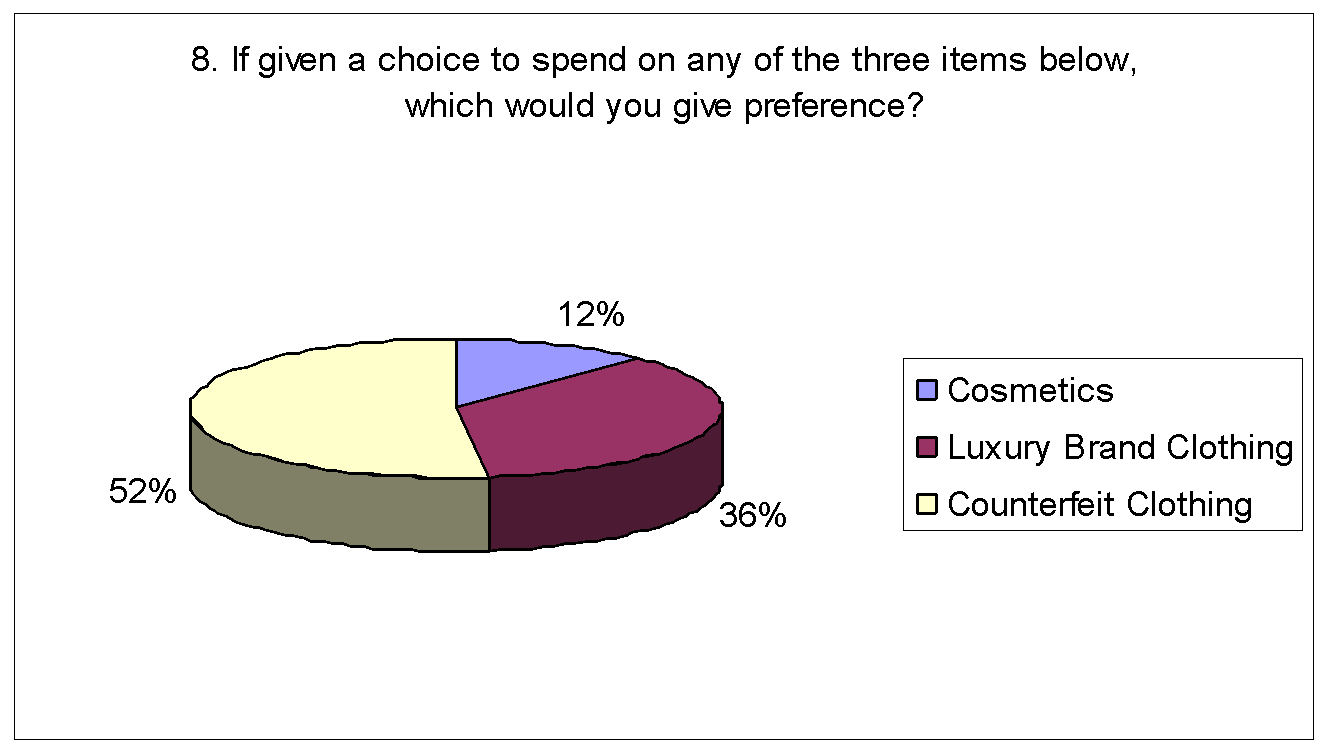

About 12% spent a considerable amount of their income on the same time frame for cosmetics, while 88% said they did not. As for the direct question on preference between luxury brand clothing against cosmetics, 36% said they go for luxury brand clothing while 32% said no. 12% preferred cosmetics over luxury brand clothing. As for counterfeit, 90% admitted to have purchased counterfeit while 10% said they never bought counterfeit.

Figure 2 provides an immediate overview on preference of the females at age group 18-35 on luxury brand clothing over cosmetics use.

The following is a tabulation of percentage of the answers of the 100 female respondents:

Table 1.

- If given a choice to spend on any of the three items below, which would you give preference (please number from 1 to 3, with 1 as the most preferred purchase)

- Cosmetics 12 (1)

- Luxury brand clothing 36 (1)

- Counterfeit brand of good quality at much lower price. 52 (1)

- If you were to choose between luxury brand clothing and counterfeit of almost indistinguishable difference with the original, what will you choose?

- Luxury brand clothing 10

- Counterfeit brand of good quality at much lower price. 90

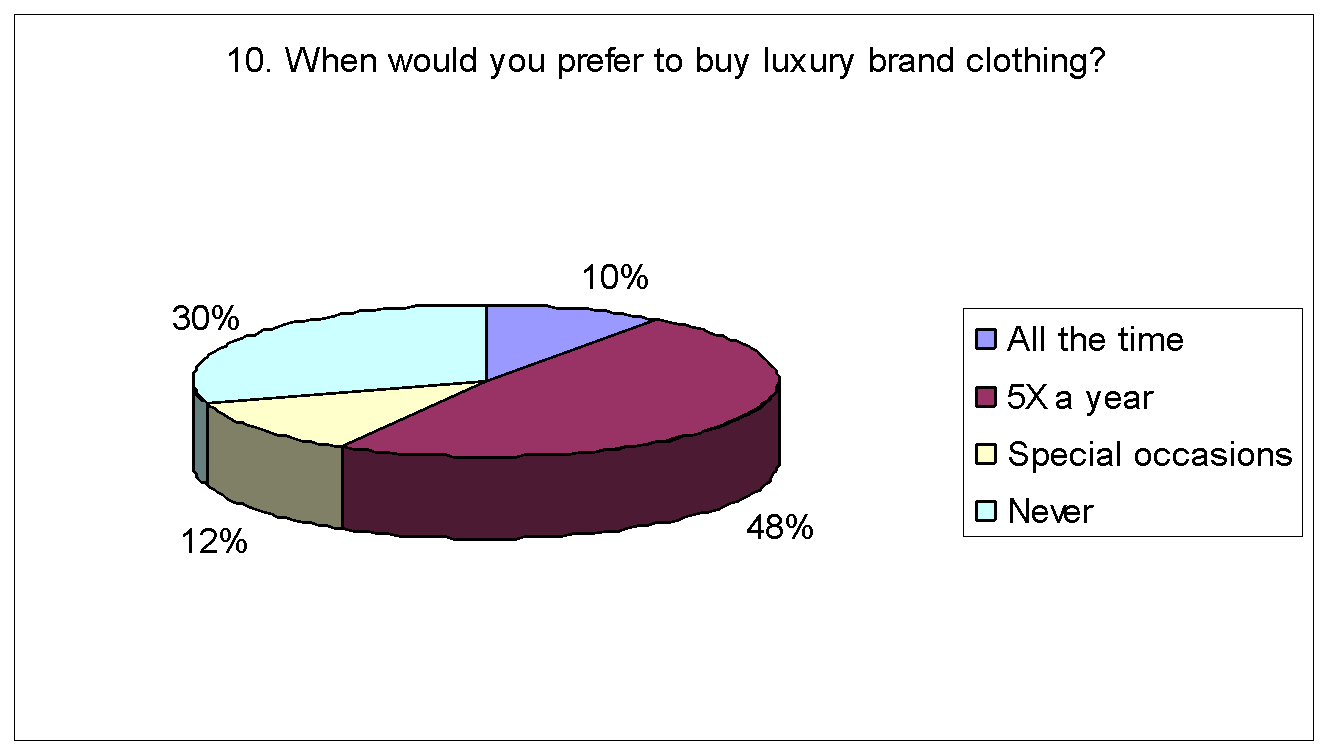

- When would you prefer to buy luxury brand clothing?

- All the time I buy clothing 10

- At least 5 times a year 48

- For very important occasion only (at least 2 times a year) 12

- Never. 30

- If you were to spend a considerable amount of money just once, which would you choose?

- Cosmetics and counterfeit luxury brand clothing 64

- Luxury brand clothing only 24

- Cosmetics only. 12

As for the preferences, 52% said they will spend on counterfeit, 36% on luxury brand and 12% prefer cosmetics. 90% have admitted to choose counterfeit closely resembling quality and material of luxury brands while 10% remain loyal to their luxury brands. 10% also admitted to always buying luxury brand clothing. When asked where to spend a considerable amount of money for just once, 64% would spend on cosmetics and counterfeit brand, 24% would spend on luxury brand clothing while 12% would spend on cosmetics.

Figure 3 provides a summation on the negative effect of counterfeit over luxury brand clothing.

To clearly provide an overview of which was the most preferred in the respondents’ expenditure, resulting pie graphs are provided below.

Analysis

In consideration of the respondents’ answers on the survey, it was evident that counterfeit products have an influence in the decision-making process of purchasing. In fact, the overwhelming majority of all respondents prefer counterfeit over luxury brands when faced to choose between the two (90%). When cosmetics are included in the choice, counterfeit brand also prevails (56%).

Nevertheless, a consistent percentage showed loyalty on luxury brands and would choose luxury brand clothing over cosmetics or even counterfeit. Also, a majority at 36% prefer luxury brand clothing over cosmetics. Same percentage of 36% also showed consistence when given the chance to spend on luxury brands, cosmetics or counterfeits.

Another consistency in the survey is the preference of 12% to have spent on cosmetics over the last three months. Overall, there is a relative influence on the purchase and use decision of cosmetics and luxury brand clothing. But more importantly, counterfeit affects the decision-making process of the majority of consumers in this survey.

The survey results suggests that luxury brand clothing, whether legitimate or counterfeit, is preferred by more consumers of the given age group and gender. This could imply that clothing is a preferred self expression or lifestyle as much as it is a basic necessity for protection. This could be understandable as it should be noted that cosmetics serve as an enhancement and not a basic necessity as much as the protection gained from clothing, therefore, it is much preferred by consumers.

Discussion

The key data of findings of the study provided that there is much preference for spending and use of clothes, luxury or counterfeit, than spending and use of cosmetics. It is also found that counterfeit greatly affects consumer decision when it comes to buying luxury brands and cosmetics.

The findings relate to objectives through provision of solid evidence among online women consumers aged 18 to 35 that there is a higher preference for purchasing physical and bodily appearance-related products such as clothing and accessories. This paper sought to investigate the purchase decision process when buying luxury brands of which the respondents showed was clearly influenced by the presence of clothing, genuine luxury brands or counterfeit. It is noted in this study, however, that luxury brand users are loyal and would stick to genuine articles. In assessing if there are differences on consumer behavior when purchasing clothing versus cosmetics, it was also found that while there is general preference for clothing, loyalty is established between luxury brand users and cosmetics users, so that buying attitude is consistent.

In exploring consumer willingness to buy and use fake articles, the study yielded mixed but related answers: the majority opt for counterfeit when they have a choice; a solid group opts for genuine luxury brands, and another solid group prefer buying cosmetics.

In investigating different consumer preferences with regards to the use of fake cosmetics as opposed to fake fashion

All of the findings supported what was researched. While a consumer behaviour model would help to find these matches, this study suggests that the necessity of clothes not only forms of protection but also as form of expression and personality enhancement made it a preferred buy among consumers. Cosmetics, as earlier noted in the review of related literature, basically provides enhancement and maintenance of physical appearance, without a very solid necessity or practicality.

What were found in this study also solidly relate to literature that clothing fashion is a bigger and much more exploited industry than the cosmetics industry although both are related to physical appearance and marketed hand-hand. The paper provided sufficient answers to the research objectives as well as tied the findings with the literature previously presented with the objective to investigate the purchase decision process when buying luxury brands.

Conclusion

This study was able to establish through the mentioned literature on luxury clothing that luxury goods or brands are those which are patented, authentic and genuine trademarked products which targets the market segment with the highest income group, as well as having expensive costs as compared to same brands or products existing in the market.

The purchase decision process for many consumers when purchasing luxury brands was associated with premium first-hand experience as well as careful scrutiny and established reputation of a retail outlet. However, other factors may be considered, among them the desire to be identified to a certain group or class, popular perception about a brand, media message on a certain luxury brand, among others. As for cosmetics, the desire to enhance one’s physical self, as well as the promise of brands or products through media messages, advertising and communications serves as the factors that persuade consumers to buy or purchase the brand or products.

In consideration of the above findings, this study found that there are a defined percentage of women who prefer to spend on luxury brand clothing as much as there is also a definite percentage who had spent on cosmetics over a given period. A trace of luxury brand loyalty can also be interpreted in the survey.

However, expenditure of women has shown preference on clothing, luxury brand or counterfeit, when it comes to choice between cosmetics and clothing. Counterfeit existence in the market shows a big influence in the buying preference of the majority as they admitted to prefer almost the same or the so-called “genuine fakes” merchandise over luxury brand clothing.

Clothing definitely is the preference for lifestyle expression among the sample of women surveyed. This may be due to the fact that clothing still serves as a necessity, a product that keeps the body safe from outside elements such as weather. Likewise, clothing is used regularly on whatever occasion or reason due to its basic service to the user. On the other hand, consumer may do without cosmetics as not all events in their daily existence require its use. Toiletries, however, are of a different plane. Individuals may proceed with their ordinary and regular routine without having to enhance their physical appearance, while individuals need a form of clothing at most of their daily schedule, from sleeping, waking, to economic or leisure activities. These may explain the prevalence of consumer preference on clothing against cosmetics purchase or use.

As for purchase between counterfeit clothing and cosmetics brands, literature provided that most cosmetics products popularly imitated which are designer perfumes are most often marketed as imposters and are clearly acknowledged by consumers as such. This study, however, did not take into consideration the preference between luxury brand clothing or luxury brand cosmetics. As for counterfeit clothing, it was established that majority of the respondents have an idea about their counterfeit purchase as they admitted to have preferred counterfeit closely resembling originals despite the prior knowledge. The high result of the preference however, indicates a negative impact on legitimate luxury brands that needs to be highlighted.

Recommendation

Since there is a definite limitation as to the population of this survey, it is highly recommended that further study in consideration of income, gender, or even race and age of respondents be undertaken and considered. It is highly probable that the majority of respondents in the survey were part of a segment market that may not be on the segment of luxury brand buyers as well as those who may not prefer use of cosmetics. Various and more extensive studies are needed to clearly identify problems that occur within the purchase decisions on luxury brands, counterfeit and cosmetics amongst various market segments. Definitely, each has a market segment that may not necessarily be the segment of another.

Cosmetics, likewise has grown exponentially when it comes to kinds and quality so that it is also necessary that a defined “form” or “kind” of cosmetics be established on further research on the matter. Cosmetic surgery, semi-permanent as well as permanent cosmetics and toiletries form various groups that may have different groups of consumers. These considerations against preference, event or situation should be carefully considered in order to gauge a clearer picture on the consumer preference.

Bibliography

Alba, J.W., Hutchinson, J.W. and Lynch, J.G., Jr. (1991). “Memory and decision making.” In TS Robertson & HH Kassarjan (eds) Handbook of consumer Behaviour (pp 1-19). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Allan, Graham, & Skinner, Chris (eds.) (1991). Handbook for Research Students in the Social Sciences. The Falmer Press: London.

American Marketing Association (AMA). (2005). Segmentation. Web.

Ang, CH., Cheng, P.S., Lim, EAC., and Tambyah, S.K. (2001). “Spot the difference: Consumer response towards counterfeits.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 18 (3), 219-235.

Associated press (AP). (2006). “PPR quarterly revenue rises 5.8 percent.” Businessweek.

Belk, RW. (1995) “A hyper-reality and globalisation: Culture in the Age of Ronald McDonald.” Journal of International Consumer Marketing 8 (3/4) pp 23-37.

R.W. Belk, K.D. Bahn and R.N. Mayer (1982). “Developmental recognition of consumption symbolism.” Journal of Consumer Research 9, pp. 4–17.

Borde, N. (1964). “The concept of the marketing mix.” Journal of Advertising Research 4, pp 2-7.

Busha, Charles H. and Stephen Harter (1980). Research Methods in Librarianship: Techniques and Interpretation. Academic Press, Inc.

Campbell, R. and Stanley, P. (1966). “Factors in Purchase Decision.” In Attitudes and Behavior (Calder & Ross, eds) 83-91. General learning Press.

Cash, Thomas (1985). “Not Just Another Pretty Face: Sex Roles, Locus of Control and Cosmetics Use.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 11 (3) 246-257.

Cash, T.F., Dawson, K., Davis, P. Bowen, M. & Galumbeck, C. (1989). Effects of cosmetics use on the physical attractiveness and body image of American college women.” Journal of Social Psychology 129, pp 349-355.

Chadha, Radha and Paul Husband. (2006). Cult of the luxury Brand: Inside Asia’s love Affair with Luxury. Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Chang, TZ and Wildt, AR. (1994). “Price, product information and purchase intention: An empirical study.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22 (1) pp 16-27.

Chattopadhyay, A. and Alba, J.W. (1988). “The situational importance of recall and inference in consumer decision-making.” Journal of Consumer Research 15 (1), 1-13.

Cote, J., Leung, S. and Schmitt, B. (2003). “Building Strong Brands in Asia: Selecting the Visual Components of Image to Maximize Brand Strength.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 20 (4), 297-313.

Childres, Terry and Akshay Rao. (1999). “The Influence of Familial and Peer-based Reference Groups on Consumer Decisions.” Journal of consumer Research 19 (2) pp 198-211.

Daily Mail. “£1 in every £4 is now spent on ‘cheap’ chic from Primark.” 2006.

Dodds, WB, Monroe, KB and Grewal, D. (1991). “Effects of Price, brand and store information on buyers’ product evaluation.” Journal of Marketing research 28, pp 307-319.

Dubois, B. and P. Duquesne (1993). “The market for luxury goods: Income versus culture.” European Journal of Marketing 27, pp. 35–44.

Dunning, D. (2007). “Prediction: The inside view,” In Higgins & Kruglanski (eds) Social Psychology Handbook of basic principles. (2nd edition, pp 69-90). New York: Guilford.

Dutka, Allan. “Product Positioning Overview.” American Marketing Association. Web.

Eagley, A.H., Ashmore, R.D., Makhijani, M.G., & Longo, L.C. (1991). “What is beautiful is good but…: A meta-analytic view of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype.” Psychological Bulletin 110, pp 107-128.

Elliot, R. (1997). “Existential Consumption and Irrational Desire.” European Journal of Marketing, 31 (3-4) pp 256-289.

Fournier, S. (1991). Meaning-based framework for the study of consumer/object relations.” Advances in Consumer Research, 18, pp 736-742.

Graham, J.A. and Jouhar, A.J. (1981). “The effects of cosmetics on person perception.” International Journal of Cosmetic Science 3, pp 199-210.

Green, R.T. and Smith, T. (2002). “Executive insights: Countering brand counterfeiters.” Journal of International Marketing 10 (4), 89-106.