Introduction

As the intensity of global competition increases, many companies are forced to reevaluate their niche in the world marketplace. For some companies, this entails strengthening their domestic position against competing for foreign products. Other firms respond by aggressively expanding their operations into foreign markets. For the individual business firm, the rapid changes in the international economy offer both threat and opportunity (Axelsson and Hekansson 1986). Streamlining, downsizing, accelerating product development, and organizational restructuring are often responses to both internal takeover threats and foreign competition (Evans et al 2004). One outcome of globalization is that corporate structures are changing and newer forms of business relationships are evolving.

Company Overview

Foster’s is a global multi-beverage company selling beer, wine, spirits, cider, and non-alcohol beverages around the globe (Foster’s Home, 2007). The history of the company goes back to the 19th century when “Jacob Beringer established Beringer Vineyards in the Napa Valley and in 1888, the first Foster’s Lager was brewed and the original Mildara Winery was established” (Foster’s Home, 2007). Today, the company operates in Australia, Asia, and the Pacific, the Americas, Europe, Middle East, and Africa. The range of business responses to the threats and opportunities in the international economy is expanding as rapidly as the global marketplace itself. The task and goals of Foster’s are to respond to coming changes and restructure its activities in order to remain profitable and competitive.

Organization Issues

Foster’s is a typical marketing organization that has four basic functions:

- marketing planning,

- product and market management,

- advertising and promotion, and

- market and marketing research.

Marketing channel members have a great impact on how Fosters can or should manage these functions. It is therefore essential that the selection of channel members and the development of channel programs be consistent with the objectives of the marketing organization that will manage the channel. Product and market management organizations like Foster’s are given special attention as channel managers in the development and management of the marketing organization channel (Johnson and Scholes, 1998).

The basic marketing channel structure consists of three components: the product source is the beginning. Next, there are the intermediaries in the channel, which are selected from a list of wholesalers, brokers, agents, retailers, or branches, and finally, there are the users or consumers of the product or products. The indirect members, or facilitating agencies, comprise the remaining group of channel members (Jacoby et al, 1998). Everyone involved in the marketing channel, from product development, physical distribution, wholesalers, and retailers to brokers, agents, and users are necessary to complete the business transaction. Foster’s performs an essential function at its respective level in the marketing channel. Foster also has specific and different needs and considerations concerning what opportunity may be sufficiently motivational to get their cooperation.

In order to support product innovation and branding efforts, a strong promotion to the user (consumer) will pull through participation from the channel levels above. Also, a strong buying program for distribution will push itself all the way to the user (Hophe & Woolf, 2003). It is also possible to create such a high selling incentive for the producer’s sales force as to achieve the prime objective by a strong selling program. Usually, all levels are considered in the planning, even if only one is included in the promotion. Foster’s channel structure is influenced by many factors. The starting place for the consideration of channel structure is the user.

Building a new channel structure or selecting the use of an existing channel structure will start from the bottom (users) and work up to the manufacturer. Knowledge of the users in a market and their buying habits is critical to channel structure requirements (Harris, 1998). Of a primary impact on a channel, the structure is the total number of potential users and their location in the market (market size and density). All the functions of product source, wholesaling, and retailing must be satisfied whether the channel is short or long and whether it is direct or has many intermediaries (McDonald & Christopher 2003; Kotler, 1991).

Different functions and different divisions will have different time horizons because of unique functions and tasks performed by each division. For instance, the Production and Quality Department must stand behind their products with reasonable guarantees where they are applicable. This department will be involved in product organization from the first stage of product development (Tayeb, 2000). Channel intermediaries are expected to handle the product quality and guarantee questions at their level, but they must be assured that the manufacturer is behind them. The marketing and Advertising Department will have more time for planning and implementation than other departments.

Their functions include stimulation of the market which relates to advertising, promotion, and the maintenance of a favorable identity for the manufacturer’s brand of products to the users and to the entire marketing channel. Communications may include product information, order processing, shipping information, and all forms of business communications. Customer Services are to fulfill regulatory and legal needs at all levels in the marketing channel and provide training, technical product service, and all necessary customer services related to products and marketing mix actions (Peter& Olson, 1990).

Members of the marketing channel must all perform their functions properly and in harmony with the other channel members. Because marketing channels with many members are more difficult to manage, manufacturers try to keep the channel as short as possible. However, even if the channel goes directly from the manufacturer to the user, none of the necessary functions of the wholesaler and retailer are eliminated (Sterman, 2000). Manufacturers, in this case, must themselves assume responsibility for the performance of these functions. So long as there is a competitive or economic justification for the existence of an intermediary member in the marketing channel, it will exist. Wholesalers and retailers that fulfill the economic role of accepting the transfer of some of the marketing costs in the channel from the manufacturer will perform a necessary service and will earn their profit according to the extent of the services they perform (Elliott & Cameron, 1994).

Organizational Type

The problem of the design of an organization is usefully informed by considering these basic properties, but it is not fully solved with the knowledge of them. Foster’s structure reflects the intended design, the past structures, and various social forces that influence beliefs about appropriate forms. Foster’s has a horizontal structure with functional differentiation, and formalization (Schuler, 1998). It is possible to say that formalization is often considered as an indicator of bureaucratization and thus to be an impediment to participation.

But a different view has also been expressed: formalization provides also protection from managerial whims and arbitrariness by giving employees clear-cut responsibilities. Since 2000, Foster’s has restructured its main activities in order to “allow the divisional MD’s to focus more completely on the market outcomes which deliver the financial goals, while at the same time forming a core central group to deliver the full service provider strategic concept. Within this structure management responsibilities will also change” (Foster’s Home 2007; Robbins, 2004).

Current Financial and Market situation

Foster’s is a market leader which operates in 155 countries around the world. The company obtains a strong market position with a pre-tax profit of 929.70 million in June 2007 (Foster’s Yahoo Finance, 2007). Wine and beer markets propose great opportunities for further development and growth. Australia is the biggest market for Fosters. “Foster’s Australian favourites include the nation’s No.1 beer, Victoria Bitter, Australia’s leading premium beer, Crown Lager, and the region’s finest wine brands including Wolf Blass, Penfolds, Rosemount, Yellowglen and Lindemans.” (Foster’s Home, 2007).

Africa and Asia represent a highly dynamic environment that requires continuous optimization of a product mix and new ways to attract customers. The market share is not large in these continents (5% of total operations). In Europe and the Americas, Foster’s obtains a strong brand image in the industry proposing high-quality products. Nevertheless, the weakness is competition and product substitution. The current company’s situation in the Americas is marked by high competition in the industry. Spirits, non-alcoholic drinks, cider, and pre-mix 4,5% of the market share and 35% of the total company’s operations (Boone& Kurtz, 1992).

External Factors and Market challenges

Taking into account these facts, it is possible to say that a brand policy of using local names will contribute to a domestic identity. The other alternative is to continue the foreign identification of the product and attempt to change buyer attitudes toward the product. Over time, as consumers experience higher quality, the perception will change and adjust. It is a fact of life that perceptions of quality often lag behind reality. In Australia, competition from new entrants and existing firms within industries provides the rationale for business strategy at the firm level. Foster’s business literature has responded to this dynamic need by proposing a variety of generic strategies for enterprises to maintain (market share in the Australian industry and maximize profits (Cairns 2003).

Silent external forces include FDI and MNCs (multinational corporations) entering the country. Also, Foster’s is affected by cost leadership (involving actions like investment in scale efficient plant, designing products for easy manufacture and R&D), differentiation (emphasizing branding, brand advertising, design, and service), and focus (stressing market niches) (Rousseau, 1997). Subsequent business strategists have refined these firm-level tactics and combined them under various slogans. Foster takes competitiveness and productivity to be synonymous. Product differentiation is the main factor that affected the Australian market (Crawford 2003; Mitzberg, 1987).

During distribution, the design delivers advantages for the company because of ‘ease of commercial effort.’ A convincing product needs less sales effort, gives free publicity, motivates the sales force (gives them self-assurance), and might even motivate others in the company. Another important aspect of the contribution of design for the company can be a ‘higher sales-price, ‘ if the design’s added value and differentiation enable the product to be positioned at a higher price point.

So-called national stereotypes and buyer attitudes toward particular countries of origin can affect the way in which export prices are interpreted in foreign markets. Customer reactions to price and the judgments that customers make will be conditioned by their perceptions and attitudes toward the country of origin of imported goods. For example, if the image of the exporting country held by buyers is favorable and the price of a product can be high. Many customers prefer to buy German beer and Italian and French wine instead of national products (Porter 1980; Prahalad & Hamel, 1994; Foster’s Home, 2007).

Foster’s Strategy for International Markets

Strategic alliances are the main strategic approach used by Foster. A primary reason for such partnerships is to create synergies not present when each of the partners acts alone. Strategic alliances are cooperative, flexible arrangements, born out of the mutual needs of firms to share the risks of an often uncertain marketplace by jointly pursuing a common objective. Strategic alliances are typically characterized in one of two different ways. The first, called a vertical, complementary, or x-type, involves agreements to cooperate in complementary activities (McDonald and Christopher, 2003).

For instance, one firm may concentrate on the design and development of the product, while the other manufactures it. Strategic alliances are the dominant mechanism used to participate in those national markets not fully open to foreign firms. Thus, in many parts of Asia and Eastern Europe, a tie-in with a local company is a prerequisite for doing business in that country. This is particularly true in countries with heavily planned economies. In these instances, it is not a matter of carefully weighing the pros and cons of building your own factory or acquiring an existing one versus teaming up with a local company (Ennew et al, 1993).

Formal governmental directives often limit foreigners to minority ownership of local enterprises, or the power of private distribution systems may yield the same result. In Indonesia, for example, all foreign investment must be in the form of joint ventures with local partners, who eventually need to own a majority share. “Foster’s Brewing Group announced today that it will acquire a 50% interest in a Japanese wine club, Wine Buzz KK, as part of its global multi-channel wine marketing strategy” (Foster’s Home, 2007).

One of the principal advantages of engaging in strategic alliances is that they give access to new or foreign markets that otherwise may be effectively closed because of the high cost of entry, governmental barriers to foreign firms, or a network of domestic enterprises that does not welcome newcomers. Alliances between companies of different nations provide opportunities to deal with whatever country has the more favorable governmental environment.

Goods can be manufactured in the country with the lowest taxes, regulatory restraints, or labor costs. Strategic alliances may be an important response to the high cost and riskiness of product development, but they are more often seen as a strategy for penetrating markets. Any number of considerations may lead a firm to consider engaging in such arrangements, however. In essence, alliances may be viewed as a means of providing the firm with a global presence when more attractive strategies are not feasible. Flexibility is one of the main operational advantages of interfirm alliances. This is particularly true for firms unable to keep up with rapidly changing consumer preferences, but which seek to meet customer demands.

Organizational Structure and Challenges WITH NEW OFFERINGS

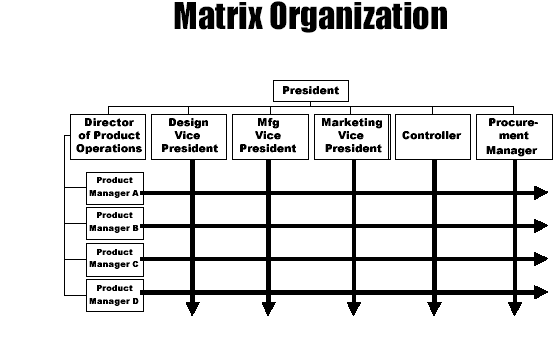

The matrix structure will benefit Foster and add flexibility. Using matrix structure, management typically finds ways to go beyond what is already established. Members are maximally autonomous, but they build on and extend each other’s work. In principle, such groups are temporary systems set up to achieve particular goals; competencies are overlapping, and size is limited. Matrix groups may produce a variety of products and may choose their own procedures and even input needs. A matrix structure tends to be widely dispersed. Long-term, directive correlations that are accepted by members focus their efforts on particular aims; correlations of this kind exist in the professions (Crawford, 2003)

The main challenges with the new product line will involve competition, price level, and customer loyalty. The new product should combine features of innovative design and unique brand image which has a great impact on the decision to purchase. Strategic benefit can therefore be gained through the integration and coherence of the organizational market and new product strategies. This integration process can be achieved by the generation and sharing of a common ‘vision’ (Dow, 1999; Crawford, 2003). This vision, a form of strategic knowledge positions and guides future work, enabling all functions to pull in the same direction, while operating reflectively and creatively. This shared vision can be reinforced through familiarity with a shared set of values that underpin all of the activities in the organization.

These values are usually tacit. Making them more explicit can encourage individuals and teams to be confident that any innovations that they generate will be broadly in line with the activities of other teams and individuals, and the future direction of the entire organization. For Foster’s, I would propose a matrix chart because it will help the company to control expectations of the customers and product quality, improve international operations and marketing initiatives (Chart 1). Also, this chart allows flexible sharing and frequent changes in changing environments, allows functional and product development. This is an ‘ideal’ chart for the company with multiple products.

In sum, the proposed organizational structure will help Foster’s to compete on the global scale and remain profitable. There is a great similarity between the domestic threat of hostile takeovers and the loss of market position owing to new foreign competition. In both cases, the firm is forced to review its strengths and weaknesses and rethink its long-term strategy and its organizational structure.

Bibliography

- Axelsson, B., Hekansson, H. 1986, “The Development Role of Purchasing in an Internationally Oriented Company”, in Research in International Marketing, Turnbull, Peter W. and Stanley J. Paliwoda, eds. London: Croom Helm.

- Boone, L.E., Kurtz, D.L. 1992. Management, 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Cairns, G. 2003, “Seeking a facilities management philosophy for the changing workplace”, Facilities, Vol. 21, num. 5/6, pp. 95-105.

- Crawford C. Merle. 2003. New Products Management. Irwin-McGraw Hill. 7th ed.

- Dow, D. 1999. “Exploding the Myth: Do All Quality Management Practices Contribute to Superior Quality Performance?” Production and Operations Management, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 1-25.

- Ennew, C. T., Reed, G. V., Binks M. R. 1993. “Importance-Performance Analysis and the Measurement of Service Quality.” European Journal of Marketing, 27, pp. 59-70.

- Evans, Martin, O’Malley, L., and Patterson, M., 2004. Exploring Direct & Customer Relationship Marketing, 2nd edition, London: Thomson.

- Foster’s Home. 2007. Web.

- Foster’s Yahoo Finance. 2007. Web.

- Hophe G., Woolf B. 2003. Enterprise Integration Patterns: Designing, Building, and Deploying Messaging Solutions. Addison-Wesley Professional.

- Johnson, G., Scholes, K. 1998. Exploring Corporate Strategy. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall.

- Jacoby, J., Johar, G.V., Morrin, M. 1998, Consumer Behavior: A Quandrennium. Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 49, pp. 34-37.

- Harris, T. 1998, Value-Added Public Relations: The Secret Weapon of Integrated Marketing. McGraw-Hill.

- Kotler, P., 1991. Marketing management, 7 th edition, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- McDonald M., Christopher M. 2003. Marketing: A complete Guide. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mitzberg, H., 1987. Five Ps for strategy. California Management Review. Fall.

- Peter, J., Olson, J. 1990. Customer behaviour and Marketing Strategy, Homewood, Illinois Irwin.

- Porter M.E. 1980. Competitive Strategy: techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York, Free Press.

- Prahalad, C.K., Hamel, G. 1994. Competing for the future. Boston: Harvard Business school Press, 202-207.

- Robbins, S. 2004, Organizational Behavior. Prentice Hall. 11 Ed.

- Rousseau, D.M. 1997, Organizational Behaviour in the New Organizational Era. Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 48, p. 515.

- Schuler, R. 1998, Managing Human Resources. Cincinnati, Ohio: South-Western College Publishing.

- Sterman, J. D., 2000. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World, Irwin McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Tayeb M., 2000. International Business: Theories, Policies and Practices, Harlow, Pearson Education.

- Elliott, G.R., Cameron, R.C. 1994. Consumer perception of product quality and the country-of-origin effect. Journal of International Marketing, Vol. 2, num. 2, pp. 49-62.