Introduction

Today, much attention is paid to the role of formal and informal education in children’s development. Their correct development is their opportunity to succeed in this life and take all options available (Ware & Beischel 2013). Therefore, educators try to introduce new techniques and investigate all fields of education in order to combine different fields, choose appropriate activities, and learn how to interact at different levels.

There are many methods that can be used by teachers in the classroom to promote student development and support the improvement of their skills and knowledge. Discourse analysis is a method used by language teachers to examine writing, spoken, and reading activities of students. This process involves looking at language form and function and analysing its main characteristics, cultural factors, and social norms.

Rationale

Discourse analysis may become an effective tool for teacher development (Rumenapp 2016). People live and communicate using different languages. A language cannot exist in isolation. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the factors that can influence the development of this process. With the help of discourse analysis, it is possible to determine the level of professionalism in the relationships between students and teachers through contextualising learning experiences and engaging students in a learning process (Domalewska 2015).

There is a thought that a gender is a factor that influences the relations between students and teachers in the classroom. Female and male teachers can demonstrate different approaches and levels of understanding of their tasks and opportunities. Students can also have different attitudes to the work of male and female teachers. Therefore, politeness strategies developed by the teachers of different genders may have different characteristics, and the task is to identify them.

Statement of the Problem

International education, multiculturalism in education, and online learning are the recent improvements in the academic field where students get new opportunities, and teachers are exposed to new standards. It is not always easy for teachers and students to understand what steps should be taken and what decisions have to be avoided in order to achieve positive results and observe effective changes.

In the UAE, a cultural factor plays an important role because the country’s traditions and social norms predetermine the relations that can be developed between students and teachers and the opportunities available. The examination of classroom discourse proves that politeness is integral in human relations, and teachers, as well as learners, have to know how to use it properly. The problem is that various factors may have a different impact on this issue’s understanding, and it is important to investigate it from various perspectives.

Purpose

In this paper, a certain attention will be paid to the development of politeness strategies in the classroom regarding the role of gender factor in teacher-student relations. The gender of teachers may determine the quality and appropriateness of interactions in the classroom, and the gender of students can influence the perception of language. Besides, there are many methods that can be used to improve discourse analysis through politeness strategies. Politeness is an intention to preserve needs, demonstrate personal attitudes, and avoid conflicts. Brown and Levinson are the developers of politeness strategies for language users and teachers (Diani 2014).

The goals of this paper include the development of a deep understanding of the politeness theory, the identification of discourse strategies with the help of which teachers may develop interactions with students, and the establishment of the gender factor as a crucial ingredient in the encouragement of politeness in the classroom discourse. It is expected to observe the results of such change in teacher-student relations and identify the impact and the role of politeness in classroom discourse, as well as the possible impact of the teacher’s gender.

Theoretical Framework

Politeness in the classroom may be discussed in terms of the theory developed by Penelope Brown and Stephen C. Levinson at the end of the 1970s. These researchers offer to consider politeness as a universal concept with the help of which it is possible to mitigate or minimise any face-threatening acts (also known as FTAs). One of the statements supported by their theory is that politeness has to be communicated by any possible means, and the absence of politeness in communication or the development of interpersonal relations has to be regarded as the absence of a polite attitude to a situation at all (Brown & Levinson 1987).

In their theory, Brown and Levinson suggest that there are four strategies that can be used to promote human politeness behaviour, including the bald on-record strategy, the off-record indirect strategy, the positive politeness strategy, and the negative politeness strategy (Brown & Levinson 1987). Each category has its own characteristics, and the task of this paper is to explain each of the theories clearly in order to comprehend which type is more appropriate for the classroom with teachers of two genders, male and female.

Brown and Levinson’s theory is a possibility to develop human actions into four different sections in regards to the presence of FTAs. The main statement of the chosen theory that a person has to be aware of face any time they start developing social relationships.

An appropriate identification of a face is a necessity in interactions with each other. A face-threatening act is defined as an activity that may result in damage to the face of an addressee that is made to meet the wants and needs of a hearer. People are taught how to avoid such acts and change their utterance or literal meaning (Lutz 2016). It is not enough to demonstrate respect and expect that people can support each other’s images. It is necessary to understand what kind of words and behaviours may change human relations and promote different understanding of the matter.

For example, there are bald on-record strategies with the help of which people should not do many things to minimise threats to their opponent’s face. Such strategies are similar to orders or requests that may sound impolite. Still, in some situations, such approach turns out to be the only appropriate solution. Imperative syntax can be used to underline urgency or irreversibility of the request. Off-record indirect strategies are the opposition to the above-mentioned strategies because they are free from any pressure.

Sometimes, instead of asking for help, people like to describe their situations and give hints so that their hearers can understand what kind of response should be given. There are also positive and negative politeness strategies according to Brown and Levinson (1987): positive strategies are characterised by friendly and trustful relations with people, and negative strategies can be used to underline some kind of imposing on people.

This theory is a core of the work with the help of which it is possible to understand what politeness strategies are appropriate in the classroom discourse and which strategies are more appropriate for female and male teachers.

Literature Review

Importance of Discourse Analysis

Discourse analysis is an important teaching and learning activity in terms of which the examination of language can be developed (Cole, Becker & Stanford 2014). It is necessary to investigate different forms of language and analyse functions a language can perform in order to provide learners without enough information for communication and skills’ improvement. Interactions between learners can occur in written and spoken forms. Therefore, learners have to understand what linguistic features are important, and what steps should be taken to consider the role of social and cultural factors (Beaulieu & Boylan 2016).

There are many forms that can be used to develop an appropriate discourse analysis in the classroom. Van Dijk (1993) offers paradigms, philosophies, and theories with the help of which national differences, personal interests, and interpersonal relations can be explained. When educators choose a discourse analysis technique, they have to know that this choice predetermines their further abilities to monitor and improve (if necessary) all classroom interactions.

Peculiarities of Classroom Interactions

The success of classroom activities depends on how well teachers can investigate all learners and make a correct technique for discourse analysis (Ryu & Lombardi 2015). However, teachers are not the only participants in classroom interactions. This process is a mutual cooperation between students and teachers. Therefore, the role of students cannot be neglected. Classroom discourse may affect different aspects of a learning process (Smart & Marshall 2013).

Students can promote a successful development of such relations demonstrating their positive emotions and intentions to cooperate with a teacher in case the later uses appropriate strategies in classroom discourse (Tobin et al. 2013). Emotions, fears, unwillingness to cooperate, and a lack of knowledge are the factors that may influence classroom activities. The task of a teacher is to identify possible threats in work with students and decide which solutions and approaches can be offered to minimise negative outcome and challenging tasks. Students have to feel confidence and comfort when they participate in classroom discussions, and teachers have to stay polite and ready to answer all possible questions.

Politeness in Classroom Interactions

There are many theories and methods that can promote discourse analysis in the classroom, and teachers have to investigate students’ peculiarities, academic goals, and opportunities to identify the steps to be taken. Classroom communication is based on teachers’ and students’ understanding of cultural and social norms (Aleksandrzak 2013). However, regardless the style of communication, the models of teachings, and the knowledge of students, it is necessary for all participants to be polite and follow the norms of communication demonstrating respect, recognition, and understanding.

Brown and Levinson are the authors of politeness strategies with the help of which they identify teachers’ and students’ perceptions of social distance, age differences, and even limitation and use of power (Senowarsito 2013). Politeness is the necessity to save “faces” of all participants of communication and interactions in the classroom and minimise the number of impolite beliefs that can influence a further development of the relations (Kurdghelashvili 2015). There are certain threats that can be observed in the classroom, and Brown and Levinson (1987) identify them as FTAs that may infringe on the needs of participants of communication to maintain their self-esteem, be respected, be heard, and be understood.

There are many examples of how FTAs may occur, including a simple request to get a piece of paper, discuss a recent language experience, or share a personal opinion on other people’s actions. It is hard to avoid FTAs in classroom discussions, and participants have to use strategies to avoid possible complications or the development of negative relations between teachers and students. Female teachers are proved to be more delicate and eager to solve conflicts with students in comparison to male teachers (Monsefi & Hadidi 2015). Therefore, a gender can play an important role in the development of polite relationships between students and teachers. However, not much research has been done in this field.

There are four main types of strategies with the help of which teachers understand what kind of work they have to do, what expectations can be established, and why certain rules and norms have to be followed. Bald on-record strategies introduce a group of actions which are defined as the most impolite approaches in communication because it usually implies an immediate completion of the order, the inability to say no or reject doing something, and the urgency of the request.

Teachers try to reduce the number of such strategies and phrases which have to be mentioned explicitly and bluntly. However, this type helps to create pressure on students and achieve the desired results in a short period of time (Senowarsito 2013). This type of politeness strategy is the representative of a “negative” face groups when the expression of restraint and independent is an obligatory task that has to be performed (Stromer-Galley, Bryant, & Bimber 2015).

Other three politeness strategies introduce a group of activities which promote a positive face when less social distance occurs between a speaker and a hearer (Peng, Xie & Cai 2014). With the help of such strategies, teachers can demonstrate their respect to students and underline their urgency in the classroom. At the same time, they can teach students how to ask for something in a polite way and achieve positive results (Manik & Hutagaol 2015).

Positive politeness strategies are used when a speaker wants to underline a high level of respect to a hearer. In such situations, teachers may begin their conversation with a question and the intentions to find out if everything is ok. Students are usually willing to cooperate with teachers who choose this type of politeness. Still, there is a need not to cross the line when a teacher can become a friend but not an educator. If a teacher allows such situation happening, it can be hard for them to put some demands on students when it is necessary.

There are negative politeness strategies with the help of which teachers can develop their relations with students. This type of communication is based on the recognition of the fact that some imposing occurs. Still, there are no other ways to omit it or neglect (Manik & Hutagaol 2015). There are certain tasks that have to be performed, certain completions that should be done, and clear instructions to be followed. Teachers may admit that such requirements may challenge students in order to underline some kind of compassion and understanding (Zhao, Ferguson & Similie 2017).

Finally, there are off-record indirect strategies which take of any portion of pressure from a speaker and a hearer. As a rule, such strategies are appropriate for the classroom where first meetings with students occur (Senowarsito 2013). Teachers should provide students with options and not impose on them certain obligations in order to develop trustful and productive relations. According to this strategy, a speaker tries to give a hint and provide a hearer with an opportunity to understand what kind of work or conclusion should be made (Zhao, Ferguson & Similie 2017). Such autonomy of hearers may lead to both, positive and negative, results in case a teacher fails to gain control over a situation when it is necessary.

Methodology

A mixed method was used to underline the main research question if a gender factor could influence the development of politeness in classroom discourse. It was necessary to combine qualitative and quantitative data in order to answer the main research concept that is the appropriateness of politeness strategies in the classroom discourse. The combination of qualitative and quantitative methods helps to support new steps and improvements through the available numerical information (Creswell 2014).

Quantitative Research: Part One

First, a questionnaire was developed to gather the opinions of students and their knowledge of politeness concept. More than 50 students from different classes in the same college were asked to participate in the survey that helped to discover their knowledge of the main politeness terms and methods that could be used to promote polite and informative communication.

It was necessary to consider several inclusion criteria, like a cooperation of students with both, male and female teachers, age measurements (students aged 15-18 years were chosen because they are able to grasp new information quickly, develop critical thinking, and understand the importance of polite and culturally appropriate communication in the classroom. Regarding such criteria and students’ willingness to cooperate, 30 students were chosen for the study.

There were five questions before the main part of qualitative research and five questions after an experiment that is going to be described in the section below. 30 students were asked to answer those survey questions in order to gather the information that they knew and compare it to the information that they had to know at their level of education. The questions that were offered before the experiment turned out to be an effective tool to identify the measurements that had been already identified by their teachers. The peculiar feature of the two-part questionnaire (another that was after the experiment) was the possibility to clarify the importance of new strategies and students’ readiness to identify their demands and abilities to follow teachers’ instructions and approaches.

Qualitative Research

After survey questions and a certain portion of answers had been developed and obtained, an experiment was introduced. It was expected to engage two teachers (male and female) using different politeness strategies (positive politeness, negative politeness, bald-on-record, and off-record). Two teachers from the same school agreed to participate in the experiment and demonstrate their approaches in cooperating with students. Both teachers used four different strategies during one week. The researcher observed the results and made notes. Every new day was a new method of communication with students.

Politeness was not the main topic of the week. Still, students were able to learn some new politeness strategies in their communication with teachers and classmates. Teachers were informed about the necessity to use different methods of communication and various politeness strategies in order to observe different reactions of students in the manner of speaking and the tasks given.

Quantitative Research: Part Two

The final part of data collection included five survey questions to be answered after the experiment was introduced. Students had to share their opinions about the strategies chosen by their teachers and their personal attitudes to the ways of how classroom discourses were developed. Besides, students were asked about the differences that could be observed between what male and female teachers said to them.

Analysis and Evaluation

In this study, the researcher took three stages in a data gathering process. First, a short questionnaire helped to clarify what students know about the importance of politeness in the classroom and if they differentiate teachers in regards to their gender. The opinions were different because a certain group of students (both, male and female) admitted that they were eager to cooperate with female teachers due to the styles of work and attitudes developed by these teachers.

In their turn, male teachers were introduced as confident and definite people with clearly identified purposes and methods of work with students. In other words, the questionnaire showed that female teachers were focused on the development of trustful relations with students and the necessity to explain everything. Male teachers, in their turn, had clear instructions and guidelines to be followed and no necessity to give additional explanations or hints in case students were provided with clear and informative guides.

At the same time, the majority of students demonstrated their high respect for male teachers. The reasons for such respect remain to be unclear: if students were afraid of their male teachers, or if their intentions were true and non-biased.

The second part of the work was the development of an experiment in terms of which two teachers, female and male, had to implement different politeness strategies in the classroom. During a whole week, both teachers chose different styles of communication and used negative and positive politeness to give tasks, ask for homework, and demand some extra work to be done. The results showed that bald-on-record strategies led to positive results and the completion of tasks in a short period of time.

In case students were asked about their willingness or free time to work additionally, many students explained their reasons for why they could not work and rejected to work. When teachers used impolite but clear requirements and expectations, only a few students refused to complete the work explaining their inability as the lack of time or the presence of plans that had been made far before the situation occurred. Positive and negative politeness was positively accepted by students and demonstrated how teachers, regardless of their gender, could gain respect and recognition among students.

Finally, the second questionnaire showed that students’ perceptions of teachers had nothing in common with a gender factor. The only thing that mattered in the case was the choice of strategies. Both teachers were accepted by the same students not because of their gender differences but because of the tactics used. If students were able to recognise their teachers’ mood, they could make use of their emotions, personal attitudes, or the presence/absence of personal needs. Still, in each situation, students demonstrated their intentions to complete all tasks and develop productive and trustful relations with their teachers, underlying the existing hierarchy.

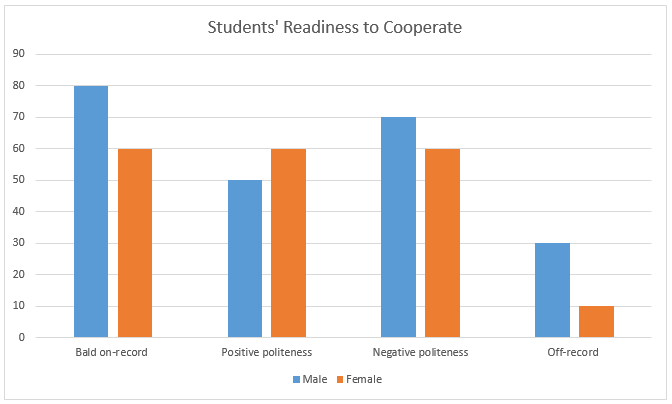

The results of students’ readiness to cooperate with teachers can be observed (Figure 1). The investigation shows that students are ready to work with teachers when they use bald on-record strategies. When teachers use off-record strategies, students do not find it necessary to listen to the orders and follow their own needs and demands. The differences between male and female teaching are minimal proving the fact that a gender factor does not play a huge role in the classroom discourse when different politeness strategies are used.

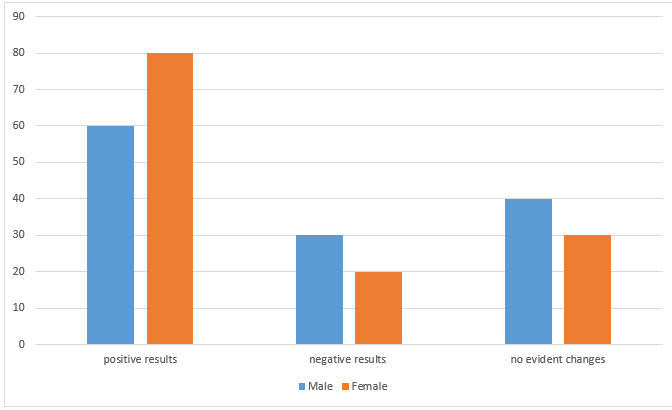

It was also proved that cooperation between students and teachers had different results (Figure 2). For example, a female teacher showed her personal interest in solving students’ problems and explaining all issues. A male teacher was not interested in the development of trustful relations with students because his goal was the development of professional relations under which students were informed about their tasks and goals and had to complete the required amount of work. Therefore, more positive results were observed in the work of a female teacher with students.

Discussion

The goal of this study is to understand the relationship between a gender factor and politeness strategies that can be developed in classroom discourse. Regarding the answers of students and the work of several teachers, the role of a gender factor has been minimised due to the effects of politeness strategies that can be used. As a rule, each teacher has their own style and certain methods of work with students. If some changes occur without any reasons, students can demonstrate different emotions and attitudes to these changes, and it is hard to make some predictions or control each interaction (Tobin et al. 2013).

The results of the questionnaires and the experiment are similar to the thoughts developed by Diani (2014) and Kurdghelashvili (2015) who believe that politeness plays an important role in an education process because it helps to define the priorities in the relations between students and teachers and promote clear explanations and guidelines that have to be followed in the classroom.

Genders of teachers are not proved as an integral factor in the development of the relationships between students and teachers. As a rule, students have to respect any teacher regardless of their gender and follow the orders and requests given. However, it was clarified that students were able to develop clear perceptions of their teachers and their styles of work with students.

For example, when a teacher prefers to be strict and rigorous, such steps as asking additional questions or being interested in students’ opinions or willingness to work as a part of a politeness strategy can cause certain doubts and even confuses students. Therefore, students do not like to observe some changes in teachers’ work but prefer to cooperate with their teachers in the same style.

Still, there are some students who were ready to share their opinions and explain why a female teacher could be a more appropriate use of politeness strategies. Female teachers prefer to investigate conflicts and provide clear and just conclusions only after all perspectives and options have been evaluated and find that it is difficult to come to a consensus with male students (Beaulieu & Boylan 2016). It means that female teachers may reduce the number of FTAs and short the distances between them and their students (Monsefi & Hadidi 2015).

The only limitation of the task is the inability or even poor attention to the relations of students to two different teachers. A certain attention was paid to the opinions and attitudes of students from their own perspectives, as well as the activities and the development of the relations between students and teachers. The fact that students cannot identify the difference in their relations with teachers of different genders was omitted.

Conclusion

In general, politeness theory developed by Brown and Levinson in 1987 was proved by the results of the recent study. Still, though politeness strategies were proved as preferred ones over negative strategies, this investigation showed that modern students find it necessary to follow the orders of their teachers that are given in an impolite way.

Insignificant differences were observed between positive and negative politeness because in both cases students are able to develop their self-images in regards to the standards of the facility. An adaptation of negative politeness strategies can lead to the achievement of effective academic results, and positive strategies lead to the reduction of FTAs in the classroom.

The achievements of the work done by male and female teachers are impressive because students do not recognise the differences between genders but focus on the methods and styles of the work they prefer. Besides, students demonstrate their abilities to recognise the mood of their teachers and the necessity to follow their orders in case they are given clearly even in an impolite way. Therefore, the role of a gender factor in the development of politeness strategies in classroom discourse can be minimised in order to clarify what other knowledge and abilities can influence a successful promotion of teacher-student relations.

Reference List

Aleksandrzak, M. (2013). Approaches to describing and analysing classroom communication. Glottodidactica: An International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11(1), pp. 129-145.

Beaulieu, R & Boylan, MA 2016, A critical discourse analysis of teacher-student relationships in a third-grade literacy lesson: dynamics of microaggression, Cogent Education [online]. vol. 3, no.1. Web.

Brown, P. & Levinson, S.C. (1987). Politeness: some universals in language usage. Cambridge: CUP.

Cole, R.S., Becker, N. & Stanford, C. (2014). ‘Discourse analysis as a tool to examine teaching and learning in the classroom’, in D.M. Bunce and R.S. Cole (eds), Tools of chemistry education research. Washington: American Chemical Society. 61-81.

Creswell, J.W. (2014). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Diani, G. (2014). ‘Politeness’, in K. Aijmer and C. Ruhlemann (eds). Corpus pragmatics. Cambridge: CUP. 169-194.

Domalewska, D. (2015). Classroom discourse analysis in EFL elementary lessons. International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, 1 (1), pp. 6-9.

Kurdghelashvili, T. (2015). Speech acts and politeness strategies in an EFL classroom in Georgia. International Journal of Social, Behavioural, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering, 9 (1), pp. 306-309.

Lutz, E. (2016). Politeness: a comparison of two pragmatic approaches towards polite acting in speech. München: GRIN Verlag.

Manik, S & Hutagaol, J 2015, An analysis on teachers’ politeness strategy and student’s compliance in teaching learning process at SD Negeri 024184 Binjai Timur Binjai-North Sumatra-Indonesia. English Language Teaching, vol. 8, no. 8, pp. 152-170.

Monsefi, M & Hadidi, Y 2015, Male and female EFL teachers’ politeness strategies in oral discourse and their effects on the learning process and teacher-student interaction. International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 1-13.

Peng, L., Xie, F. & Cai, L. (2014). A case study of college teacher’s politeness strategy in EFL classroom. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4(1), pp. 110-115.

Rumenapp, JC. (2016). Analysing discourse analysis: teachers’ views of classroom discourse and student identity. Linguistics and Education, 35, pp. 26-36.

Ryu, S & Lombardi, D 2015, Coding classroom interactions for collective and individual engagement, Educational Psychologist, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 70-83.

Senowarsito 2013, Politeness strategies in teacher-student interactions in an EFL classroom context. TEFLIN Journal, 24 (1), pp. 82-96.

Smart, JB & Marshall, JC 2013, Interactions between classroom discourse, teacher questioning, and student cognitive engagements in middle school science, Journal of Science Teacher Education, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 249-267.

Stromer-Galley, J., Bryant, L. & Bimber, B. (2015). Context and medium matter: expressing disagreements online and face-to-face in political deliberations. Journal of Public Deliberation, 11(1), pp.1-24.

Tobin, K., Ritchie, S.M., Oakley, J.L., Mergard, V. and Hudson, P. (2013). Relationships between emotional climate and the fluency of classroom interactions. Learning Environments Research, 16(1), pp. 71-89.

van Dijk, T.A. (1993). Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 4 (2), pp. 249-283.

Ware, ME & Beischel, ML. (2013). “Career development: evaluating a new frontier for teaching and research”, in M.E. Ware and R.J. Millard (eds). Handbook on student development: advising, career development and field placement. New York: Routledge. 132-134.

Zhao, K., Ferguson, E. & Similie, L.D. (2017). Politeness and compassion differentially predict adherence to fairness norms and interventions to norm violations in economic games, Scientific Reports [online]. vol.7, no. 3415. Web.