Abstract

Gestational diabetes is a prevalent obstetric problem. The outcome may affect both the mother and the neonate. This essay aims at providing a brief, yet, comprehensive review on gestational diabetes, clarifying the key caring components, discussing the role a midwife can play as a part of a health care team, and finally inferring the challenges that face midwives dealing with this condition.

Introduction

Although childbirth is a natural process; yet, midwifery is the art and science of practicing care to assist females at all stages of the childbirth process (pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum) (Liburd 1999). The word challenge carries many connotations, it points to the demanding task of proving, as well as winning a situation against opposing or difficult circumstances (Soanes and Hawker 2008).

Vibeke and colleagues (2009, p. 1349) defined gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) as glucose intolerance detected for the first time during pregnancy. They considered GDM a significant forecaster for type II diabetes mellitus (DM) since females with GDM are sex times prone to develop type II DM than non-GDM mothers.

Professional midwifery aims to enhance maternity care through capitalizing on maternal and fetal outcomes. This concept reveals a promising model of maternity care systems where midwives are key members of primary care providers and a significant link between community care providers and the healthcare system (ICM 2003). This essay aims to look at the problem of GDM and accept the challenge of clarifying a management framework from a midwifery viewpoint.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

Glucose is an important metabolic substrate for the fetus as it is for the mother. Since it crosses the placental barrier by facilitated diffusion, GDM is a risk to the mother and the fetus. (Habermann and Ghosh 2008).

Etiology and pathogenesis

Diabetes is the result of inadequate insulin supply to meet the needs of the tissues for blood glucose regulation. Regarding GDM, two specific points are worthy to mention; first, pregnancy is associated with increased insulin resistance starting in the second trimester, progressing through the third trimester to reach levels similar to type II DM. Insulin resistance in GDM is likely to be the result of a combination of lifestyle factors (nutrition and overweight) and the insulin-desensitizing effect of chorionic gonadotrophins (placental hormones). This is evidenced by the fact that GDM subsides in many cases after delivery (Buchanan and Xiang 2005).

Second, to compensate for increased insulin resistance in pregnancy, the pancreatic B cells increase their insulin secretion. Therefore, changes in blood sugar levels during pregnancy may be small especially when compared with the larger changes in insulin resistance (Buchanan and Xiang 2005).

The American Diabetes Association (2003) identified three risk groups of GDM and recognized the assessment clinical characteristics for each one. First, the high-risk group where only one of the following criteria is sufficient: marked obesity, DM in a first-degree relative, history of glucose intolerance, current glycosuria, or history of delivery to an overweight child (macrosomia). Low-risk group mothers should have all the following criteria to be at risk of GDM: age less than 25 years, no history of macrosomia, no history of glucose intolerance or glycosuria, and normal pregnancy weight.

Prevalence

Dabella et al (2005, p.579) suggested that 3-8% of all pregnant mothers in the USA show GDM; however, the impression is this rate is increasing because of increased obesity prevalence. Further, the authors stressed that different ethnic show different prevalence rates, being more common in African Americans, Hispanic and Native Americans.

In the UK, Hanna et al (2007, p. e 64) noticed that different studies reported different prevalence rates ranging from 3-4% to 2-9%, the reason is that rates vary in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. However, they noticed that areas with the highest prevalence of GDM do not automatically match those with the highest rates of DM in the general population.

Link and McKinlay (2009, p. 288) inferred socioeconomic status shows a stronger association with GDM than racial or ethnic factors. They clarified that continuing stress on biomedical factors of different races or ethnic groups would circumvent efforts of socio-medical interventions.

Diagnosis

Clinically, cases of GDM may show symptoms similar to those of type II DM like thirst, increased urination frequency, fatigue, frequent infections, unexplained weight loss, and nausea and vomiting. However, these symptoms can be attributed to pregnancy or the condition is asymptomatic and detected only on screening. Therefore, although screening is recommended at 24-28 weeks of pregnancy; yet, it is advisable to consider each case separately based on the classification of risk provided by the American Diabetes Association (2003), (Boinpally and Jovanovich 2009).

GDM is screened by oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) of either the 1-step or 2-steps method. One-step OGTT is a glucose load of 75-100 grams of glucose taken orally after a fasting period without previous plasma screening. The two-step approach to administer a first 50 grams OGTT if the glucose level result equals or more than 130mg/dL, the test is followed by a one-step OGTT to confirm the diagnosis (Boinpally and Jovanovich 2009).

OGTT is recommended mostly between 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy, however, some authorities recommend in addition a first antenatal visit screening test, while others recommend screening at 20, 28, and 34 weeks gestational age. This discrepancy is because GDM may progress as pregnancy advances (Coustan 1995).

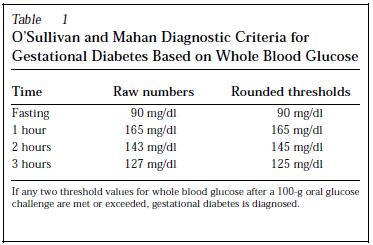

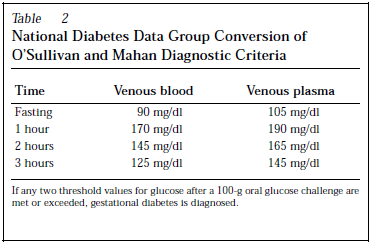

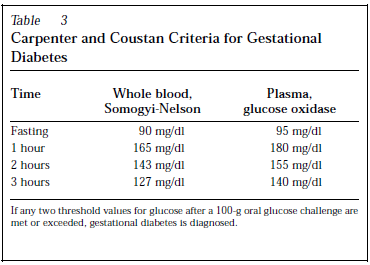

Diagnostic criteria varied in different studies but the commonest in use are O’Sullivan and Mahan Diagnostic Criteria, National Diabetes Data Group Conversion of O’Sullivan and Mahan Diagnostic Criteria, and Carpenter and Coustan Criteria for Gestational Diabetes.

Maternal and fetal outcomes

Mothers with GDM are more prone to develop type II DM after delivery; further, they have high recurrence rates (30-69%) of developing GDM in subsequent pregnancies. There is a strong association between GDM and hypertension; therefore, GDM mothers are liable to develop further complications of pregnancy like preeclampsia (Evans and Patry 2004).

There is a belief that GDM is associated with higher rates of fetal death; however, there are no well-designed trials to support this opinion. The characteristic fetal complication of GDM is macrosomia defined as an infant born weighing more than 9 lb (8.8-9.lb). Evidence shows that the prevalence of macrosomia is 14 to 23% in GDM mothers.

The main complication associated with macrosomia is shoulder dystocia (obstructed labor secondary to impaction of the anterior shoulder under the maternal symphysis pubis). This complication may lead to fatal injury or serious maternal hemorrhage secondary to injury or uterine atonia (Evans and Patry 2004). Another serious fetal complication is neonatal hypoglycemia which may lead to neonatal coma or death if not detected (Evans and Patry 2004).

Philips and Jeffries (2006 p. 701) showed that shoulder dystocia occurs in 3% of deliveries to mothers with GDM, and in this group, 71% of the infants are admitted to a neonatal nursery. They also showed that if a GDM mother is not given care, the risk of serious pregnancy complications rises threefold that in non-GDM mothers.

Management outline

There are two essential cornerstones for proper management, first, is lifestyle interventions which include diabetes nutritional therapy and encouraging exercise. The second is achieving a normal blood glucose level through medication therapy. For this purpose, insulin is still preferred over oral hypoglycaemic agents mainly because of its large molecular weight which prevents crossing the placental barrier to the fetus. Of importance is to look for impending complications or coexisting medical disorders like hypertension (Habermann and Ghosh 2008).

Key GDM caring components

Before discussing the key care components, it is essential to clarify that management of GDM needs a team approach of which a nurse-midwife is an indispensable member. The care plan should be tailored individually considering factors like the mother’s age, work schedule and environment, lifestyle pattern, social situation, personality, cultural norms, and the presence of diabetes complications or coexisting disease. The care planning process should include evaluation of the patient’s individual education needs and identify the potential of the mother’s self-management (Belfiore and Mogensen 2000).

The American Diabetes Association (2007) identified seven pillars for diabetes care, initial evaluation, glycemia control, medical nutrition therapy (MNT), diabetes self-management education, encouragement of physical activity, psychosocial assessment and care, and referral for diabetes management. The report emphasized the team approach for providing care and that the best possible diabetes care needs an organized systematic approach with the effective participation of each member of the healthcare team.

Midwifery care to mothers with gestational diabetes

Cheung (2009) summarised the area a midwife can participate in providing healthcare to a GDM mother as patient education, dietary and exercise therapy, diabetes self-management education.

Patient education

Patient education about diabetes is essential in GDM as during pregnancy the healthcare team is working on two patients simultaneously; the mother and the fetus. An education program should focus on the importance of maintaining treatment and changing the lifestyle, it should also focus on possible complications if management is neglected. The program should have a goal e.g. reduce the risk of complications, decrease hospitalization to control diabetes, or constant reevaluation of the treatment plan. On implementing an education program there should constant evaluation of the outcome based on the benchmarks determined earlier (Pagano et al 2006).

Kim et al (2007) considered GDM a teaching moment where patients are receptive to education to decrease the risk of GDM. In their series, they found that patients who had GDM in a previous pregnancy remembered health care providers’ advices facilitated by brochures or lab slips on screening. They inferred that in cases of the previous history of GDM, preconception preventive counseling is an important area to look at. Understanding the working environment, cultural, social, and patient’s self-care behavior is essential to reduce escape from educational settings (Gucciardi 2008).

Encouraging exercise and physical activity

The American Diabetes Association report (2007) acknowledged exercise as an important means of controlling diabetes and preventing possible cardiovascular complications. The report suggested an exercise dose of 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity exercise or 90 minutes per week of intense exercise. Regarding frequency, the report suggested that exercise should be maintained at least three times per week with no more than two consecutive days without exercise. In absence of cardiovascular complications, patients are encouraged to practice resistance exercise gradually increasing to reach 8-10 minutes three times per week.

Downs and Ulbrecht (2006) examined exercise beliefs and behaviors in postpartum females who had GDM in a recent pregnancy. They inferred the main motive during pregnancy was to control GDM, while in the postpartum, it was weight control. Only 7% of exercising females in the postpartum were aware this may prevent type II DM. The husband or partner encouragement had the strongest influence, while the main barrier during pregnancy was fatigue and during the postpartum was lack of time. This information would enlighten designing proper exercise education programs.

Dietary management

Dietary therapy aims to provide enough mothers and fetuses nutrition in terms of calories and various food elements; however, the diet must be planned to allow weight gain yet maintain suitable blood glucose levels avoiding the risk of complications e.g. coma or kentonuria. Regarding weight, a gain diet should be planned according to body mass index (BMI) allowing lesser weight gain for females with higher BMI indices. How nutrients are distributed all through the day is controversial (Di Cianni et al 2008).

The indication for medical treatment whether insulin or oral hypoglycaemics is when the patient fails to achieve a balance between nutrient needs and glucose level. Medical nutrition therapy should be looked at as a self-management therapy; therefore, GDM patients need education and support for a successful outcome (Reader 2007).

Diabetes self-care management

Diabetes self-care management means providing the patient with information and education on how to self-monitor blood glucose, dietary counseling, how to achieve a healthy lifestyle. Therefore, a midwife may be able to fulfill these goals and the health care team may then need a dietitian and or a diabetes educator (Cheung 2009).

Cultural support

Providing support that crosses cultural diversity and considers psychosocial factors influences, to a great extent, the patient’s acceptance of health care services especially in a culturally diverse population. This is by no means an easy task as the difficulty is not societal diversity but within a specific group, the degree of culture absorption and changeability (acculturation) varies (Mendelson et al 2008).

Mendelson and colleagues (2008) inferred that acculturation has an impact on pregnancy beliefs and practices in different ethnic groups. The authors suggested a tendency towards living by two cultures (biculturalism) rather than absorbing the new cultural value and coming up with a unified culture.

Conclusion

Midwives face three challenges regarding gestational diabetes, first, can they meet the basic belief of the midwifery care model that is childbirth is a natural procedure and they should only interfere when necessary? Second, can they provide GDM patients’ care as a part of a team whose primary concern is the patient’s welfare? Third, can they be practical; yet creative to cross barriers and provide better health care to GDM mothers.

References

American Diabetes Association (2003). Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care, 26(Suppl. 1), S5-S20.

American Diabetes Association (2007). Position Statement: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 30 (Suppl. 1), S4-S41.

Belfiore, F., and Mogensen, C. E (2000). New Concepts in Diabetes and Its Treatment. Basel: Karger.

Boinpally, T., and Jovanovich, L (2009). Management of Type 2 Diabetes and Gestational Diabetes in Pregnancy. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, 76, 269-280.

Buchanan, T. A., and Xiang, A. H. (2005). Gestational diabetes mellitus. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 115(3), 485-491.

Cheung, M. W (2009). The Management of Gestational Diabetes. Vascular Health and Risk Management, 5, 153-164.

Coustan, D (1995). Gestational diabetes. In Diabetes in America (2nd edition). [NIH Publication no. 95-1468]. US Govt. Printing Office. Washington, DC.

Dabella, D., Snell-Bergeon, J. K., Hartsfield, C. L., Bischoff, K. J., et al (2005). Increasing Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) Over Time and by Birth Cohort: Kaiser Permanente of Colorado GDM Screening Program. Diabetes Care, 28(3), 579-584.

Down, D. S., and Ulbrecht, J. S. (2006). Understanding Exercise Beliefs and Behaviors in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care, 29, 236-240.

Evans, E., and Patry, R (2004). Management of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Pharmacists’ Role in Patient Education. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 61(14), 1460-1465.

Di Cianni, G., Fatati, G., Lapolla, A., Leotta, S. et al (2008). Dietary therapy in diabetic pregnancy: recommendations. Mediterr J Nutr Metab, 1, 49-60

Gucciardi, E (2008). A Systematic Review of Attrition from Diabetes Educational Programs: Strategies to Improve Attrition and Retention Research. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 32(1), 53-65.

Habermann, T. A. and Ghosh, A. K (2008). Mayo Clinic Internal Medicine Concise Textbook. Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic Scientific Press.

Hanna, F. W. F., Peters, J. R., Harlow, J., and Jones, P. W. (2007). Discrepancy between Postnatal and Antenatal Management of Gestational Diabetes in the U.K. Diabetes Care, 30(7), e64.

ICM (2003). The essential competencies of midwifery practice. Geneva: International Confederation of Midwives.

Kim, C., McEwen, L. N., Kerr, E. A., Piette, J. D., et al (2007). Preventive Counselling among Women with Histories of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes are, 30, 2489-2494.

Liburd, A. (1999). The use of complementary therapies in midwifery in the U.K. Journal of Nurse Midwifery 44(3), 325–9, 183–188

Link, C., and McKinlay, J. B (2009). Disparities in the Prevalence of Diabetes: Is It Race/Ethnicity or Socioeconomic Status? Results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Ethn Dis, 19, 288-292.

Mendelson, S. G., McNeese, D., Koniak, D., Nyamathi, G. A., et al (2008). A Community-Based Intervention Program for Mexican American Women with Gestational Diabetes. JOGNN, 37, 415-425.

Pagano, M., Luressen, M., and Esposito, E (2006). Sustaining Diabetes in Pregnancy Program: A Continuous Quality Improvement Process. The Diabetes Educator, 32(2), 229-234.

Philips, P. J., and Jefferies, B (2006). Gestational diabetes: Worth finding and actively treating. Australian Family Physician, 35(9), 701-703.

Reader, D. M (2007). Medical Nutrition Therapy and Lifestyle Interventions. Diabetes Care, 30 (Suppl. 2), S188-S193.

Soanes, C. and Hawker, S (2008). Oxford Compact English Dictionary of Current English (third edition). London: Oxford University Press.

Vibeke, A., van der Ploeg, H., P., Cheung, A., W., Huxely, R., R. et al (2009). Sociodemographic Correlates of the Increasing Trend in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Large Population of Women between 1995 and 2005. Diabetes Care, 32, 1349-1352.