Introduction

Since the beginning of the 20th century, globalisation has been the main driver for international trade. Even though the interaction of communities is not a new phenomenon, globalisation has stirred many debates, both politically and socially, about its potential ramifications to human societies.

To this extent, it is difficult to analyse the dynamics surrounding globalisation in one perspective because there are many views surrounding its existence (Study Mode 2013, p. 1). Besides basing its principles on a broad division of labour, globalisation has evolved into a sophisticated international wealth distribution system that transcends traditional structures of trade and economic development.

The globalisation debate has created two opposing groups who either advocate or oppose the practice. Proponents of globalisation support one hand of the debate when they say that we live in a globalised world (already) and an attempt to limit globalisation is futile.

The other side of the divide is comprised of people who oppose globalisation, based on the presumption that the world is not globalised yet, and attempts to forestall this development should be improved (Volkman 2006). The varied views of these opposing groups trace to the differences in the definition of globalisation that both groups have.

Differences in opinions regarding whether it is right to embrace globalisation or not spreads to different companies which also consider whether to embrace globalisation as part of their core business practices, or not. This paper focuses on one such company in California, which focuses on producing personal computers and other communication devices.

One group of consultants say the telecommunication company should keep all its activities within California, but another group of consultants say the company should distribute its activities equally in Asia, Europe, and America.

This paper explores both arguments by evaluating the impact of currency value, customer behaviour, value addition, competitive advantage, cooperative advantage, outsourcing, foreign direct investments, and the debates for globalisation and against globalisation.

Anti-Globalism Perspective

Supporters of the anti-globalism movement often highlight the excessive wield of political power by a few multinational companies as a criticism for globalisation. This excessive political power partly thrives from the deregulated financial market and the numerous trade agreements that support international trade.

Mainly, people who support the anti-globalism movement say the willingness to make supernormal profits by multinational companies mainly drives their quest to engage in international trade, such that, they overlook the well-being of their workers and other social and environmental concerns (Goodman 2005).

Some anti-globalism crusaders have also said multinational companies ignore the sovereignty and legitimacy of independent governments as they go about their business, globally. Such concerns have convinced many people to believe that globalisation is a bad thing.

Some people also believe that a few multinationals have turned globalisation to be an opportunity for a few individuals and interested parties to exercise some privileges that ordinary people cannot (Zanfei 2005). Such privileges include the free movement of people across borders, the exploitation of natural resources, and the exploitation of human resources.

One argument that stands out in this debate is the role of globalisation to cement the authority of industrialised nations over poor nations. For example, Sintonen (2002) believes that globalisation is unfair to developing nations because there is an unequal interaction between developed and developing nations.

Indeed, most developed nations wield a lot of power in both economic and political fronts. Therefore, developing nations always find themselves disadvantaged against most of the major world powers. Comprehensively, anti-globalism crusaders say globalisation is not healthy for the developing world.

Political Debate

The political debate surrounding globalisation has mainly centred on conservative and liberal sentiments towards the issue. A common argument advanced by conservatives is the protection of nationalistic sentiments (Akisik 2009). Indeed, politically, globalisation erodes the social fabric that characterises different societies.

This happens because politicians base their principles on the differentiation of basic social ideologies. The fact that nationalism outlines the foundation of modern society and social cohesion further exacerbates these fears (MrGlobalization 2011).

Therefore, some people fear that the elimination of these social and political structures may threaten national unity and patriotism. This is the main fear characterising the arguments against globalisation in the political front.

This argument closely resembles similar arguments, which preserve cultural identities because some people fear that globalisation erodes unique cultural and nationalistic values. To this extent, anti-globalisation sentiments try to protect nationalism and individualism.

The concept of individualism has also spread to corporate governance because some companies fear that going global erodes some of their core corporate values (Akisik 2009). This may be the main idea informing the hesitation by the California-based technology company to distribute its activities to Asia, Europe, and America.

Why Economists Resist Anti-Globalism

Analysts have a very different concept of globalisation when they review the same argument economically. By most measures, globalisation makes a lot of economic sense because it uplifts the economic well-being of societies (though unequally).

Indeed, globalisation creates several economic benefits, such as, capital mobility, development of infrastructure, development of sophisticated financial products, liberalisation of economies, and the growth of companies. These reasons have prompted many economists to resist the anti-globalism movement.

Why the Californian-Based Company Should Remain Local

Changing Customer Behaviour

The introduction of globalisation has brought new challenges regarding transcending social and cultural differences. Indeed, different societies around the world have unique differences in their social and cultural compositions, which affect their customer behaviours (McLaughlin 1996).

Therefore, for instance, there is bound to be significant differences in the customer behaviours of European, Asian, and American shoppers. These differences pose a challenge to companies that intend to market their products across different geographic regions. This challenge manifests because different customer groups respond to the same product differently.

Therefore, while a product may report higher sales in America and Europe, it may report poor sales in Asia. This difference has forced many companies to tailor-make their products to meet the social and cultural dynamics of their target market (Iqbal 2006).

However, this process requires additional resources in manufacturing and marketing. Therefore, companies that experience these challenges face rising production and manufacturing costs, which erode their profitability.

Therefore, in the context of this study, different consumer behaviours (brought by differences in social and cultural dynamics) impede the market opportunities for the California-based technology company to transcend its traditional market.

Therefore, the difference in consumer behaviour hampers the distribution of the company’s activities across Asia, Europe, and America. To this extent, limiting the company’s activities within California seems like a safer option.

Nevertheless, researchers have explored the concerns regarding globalisation and cultural differences. Even though there may be a popular perception that cultural differences impede globalisation, many people ignore the power of globalization to overcome this challenge.

Bobek (2005) contends that globalisation has the power to disrupt fragile societies and traditional identities to create a more “globalised” system of multiculturalism. People who support the anti-globalisation movement have used this power to say globalisation threatens the existence of unique cultural identities (Alvarez 2010).

The fear that consumer cultural differences may slowly disappear and traditional customs and practices eliminated by the spread of globalisation informs their fear.

Economically, the elimination of cultural differences may be a good thing because it also means the elimination of different consumer behaviours. In a highly globalised society, it is easy to sell one product to a large consumer group without having to embrace different cultural dynamics.

Nonetheless, this fact does not mean globalisation does not tolerate cultural dynamics because it does. For example, it is easy to find different cultural cuisines (such as Mexican, Thai, or Indian food) in an urban restaurant. Similarly, even in a globalised system, cultural differences in education, media and finance are still upheld (Harney 2006).

Therefore, even though cultural differences may lead to differences in consumer behaviour, it still does not dampen the prospects of a flourishing global society because globalisation has the power to overcome differences in customer behaviour to create a multicultural system where people consume goods and services with minimal behavioural limitations.

Therefore, through this analogy, differences in customer behaviours may not necessarily inhibit the spread of company activities beyond California.

Why the Californian-Based Company Should be Global

Fluctuations of Currency Value

Different factors affect currency values. However, the principle factor affecting a currency’s value is the currency’s demand. Currency value determination is important in international trade because different countries (or regions) trade in different currencies.

For example, the exchange of dollars and Euros characterises the trade between Europe and America (a trader may exchange one Euro for one and a half dollars).

The impact of currency values in international trade cannot be underestimated because the value of a currency normally determines a country’s import and export volume (Hamel 2012, p. 1). For example, when the British sterling pound has a high value, Britons are likely to demand more goods and services from the international market.

The high demand for goods and services may increase their volume of imports. Similarly, if the U.S. dollar decreases in value, foreign goods are likely to be more expensive for Americans and this may reduce America’s import volume in the future (Mraovic 2010).

Conversely, a poor dollar value is likely to make U.S. goods more attractive to the international market. Therefore, a low dollar value is likely to improve the attractiveness of U.S. exports.

The influence of international currency values on the activity of international companies also takes the same form as the examples described above. The main difference between local companies and international companies stem from the influence of currency fluctuations on company activities.

Therefore, depending on the activities of these companies in the international market, currency fluctuations may erode profitability or reduce the production costs of these companies.

By focusing on the case study in this paper, if the California-based technology company distributes its activities across three continents, it may take advantage of the lowest currency values to reduce some of its production costs. For example, low currency values in developing countries are attractive to international companies because they reduce their wage bill (Pakravan 2011).

Therefore, the Californian technology company may reduce its wage bill by using relatively cheaper labour in developing countries to reduce its overall production costs. Indeed, limiting its activities within California means the company will pay higher wages to its workers because of the high value of the U.S. dollar (compared to some developing markets abroad).

Therefore, exporting some of its production processes abroad reduces the company’s wage bill. Such cheap labour may come from Asia or certain parts of Europe.

Many technology companies have taken advantage of such opportunities to reduce their production costs. Apple Inc. is one such company, which has exported some of its production processes to overseas markets (notably China) (Prestowitz 2012, p. 1).

Even though the company has come under intense criticism from Americans for exporting American jobs to overseas markets, Apple Inc. has said that bringing the jobs back to America will increase its wage bill so high that it will make the company less competitive in the end (Prestowitz 2012).

Apple is however, not the only company that takes advantage of the difference in currency value to increase its competitiveness, European carmakers have also exported some of their production processes overseas to reduce their wage bills.

For example, Mercedes Benz and BMW have exported some of their manufacturing activities to Asia and Africa, then re-exported back the finished products to Europe to exploit the differences in currency value as a measure of reducing their production costs.

Many more companies are following this example because globalisation has opened new opportunities for companies to reduce their production costs by taking advantage of differences in currency values. The California-based company also needs to exploit this opportunity by distributing some of its activities overseas to increase its market competitiveness.

Value Addition

Globalisation complements a company’s value addition process. Value addition mainly occurs through the trade of intermediary inputs. As Johnson (2011), observes, this market segment (trade of intermediary inputs) accounts for about two-thirds of all international trade.

Intermediary trade supports value addition through globalisation because globalisation thrives on the principle that one location does not have all the competencies and positive attributes needed to make a product or deliver a service (Steingard 1995). The absolute advantage theory explains this principle.

Adam Smith (the founder of the theory) explains that a company can realise business success in another country if it establishes its absolute advantage. For example, countries that have natural advantages like a better geographic location, cheap labour, fertile land, and production resources (like human resources) have a strong business advantage over other companies that do not have these resources.

For example, the California-based technology company may use some of its core competencies to gain a strong business advantage over its main competitors (David 2010). These advantages define its absolute advantages to use over its competitors.

The main weakness of the absolute advantage theory is its failure to analyse countries that have no absolute advantage (at all). In the same regard, this theory does not give any provision to countries that have all absolute advantages (this has been its primary basis of criticism) (David 2010, p. 11).

Therefore, international trade thrives on the basis that one country (or company) may demonstrate key weaknesses and competencies in providing a product or service. Consequently, through international trade, consumers may combine the advantages of different countries in producing one product (McPhee 2006).

Therefore, instead of limiting a company’s production process to the key competencies of one region, it is better to incorporate the key competencies of different countries in producing the same product.

When applying the same concept in the context of this paper, it is vital to point out that limiting all company activities within California prevents the possibility of the company to add value to its products.

In fact, by limiting all its activities within California, the company would not enjoy the key competencies of other locations, such as, Asia or Europe. This way, the company would not enjoy value addition opportunities.

Countries that enjoy value addition services also enjoy the increased fragmentation of production processes across different geographic regions, thereby taking advantage of the opportunity to add value to their products.

For example, a technology company that has fragmented its production processes to incorporate Korean production processes enjoy the embodiment of Korean value processes as it exports its products to Europe. Therefore, a fragmented production chain means there is a hidden structure of value addition, which companies and countries enjoy through international trade.

A careful analysis of this value addition process is often vital to understand how different countries link in the international trade system.

Cooperative Advantage

Globalisation has changed the dynamics of the way businesses operate. It is, therefore, unsurprising that many companies fear the impact of globalisation.

Indeed, globalisation has introduced a new business environment that thrives on efficiency, supply chain optimisation, and cooperative advantages. With the new rules of business engagement, Britt (2007) says, businesses need to collaborate with one another to gain some cooperative advantage. Globalisation offers businesses this opportunity.

For example, European car automakers are seeking new partners to help them improve their core business advantages. Even though some European car automakers have a high engineering precision and top-notch manufacturing, they are still exploring new opportunities for improving their business processes through collaborating with other companies around the continent.

Through these partnerships, a Finland-based company assembles the Porsche Boxter (which is a German product), while a company based in Austria assembles some BMW car brands (also a German product). This way, German car automakers improve their cooperative advantages.

The California-based technology company may equally exploit such market opportunities to improve its cooperative advantage. Indeed, some overseas technology companies may improve the company’s core business processes by polishing its production processes.

This way, the company may improve its cooperative advantage and join the league of other international companies in exploiting such opportunities.

Competitive Advantage

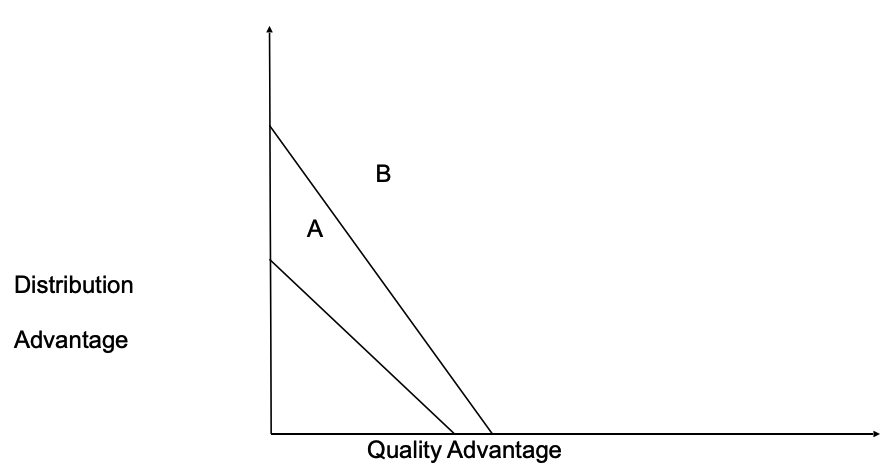

Competitive advantage refers to the ability of a company (or country) to position itself well within its environment. The competitive advantage theory best explains this phenomenon because it supports the best use of resources at a local, domestic, and global level (Goel 2009, p. 1). For example, from the diagram below, two different companies show different competencies – distribution advantage and quality advantage.

Assuming that letter ‘B’ represented the California-based company and the letter ‘A’ represented its main competition, the above diagram shows that the technology company has a better distribution and quality advantage over its main competitor.

Therefore, company ‘B’ would have a stronger competitive advantage over its competition. Therefore, the company should receive most manufacturing opportunities.

The competitive advantage theory, therefore, supports the idea of a globalised manufacturing process, which also complements the idea of the diversification of company processes across different geographic regions (Vaccaro 2009).

Foreign Direct Investments (FDI)

Global companies are the main drivers of international trade through their high foreign direct investments. In fact, Estrin (2012) says foreign direct investments are the main drivers of a globalised society. Recently, researchers have explored the impact of FDIs on different economies and the impact of such investments on the local economy and the investing companies.

These literatures show that most multinational companies that invest in overseas markets do so, not because of the political or economic advancement of their target markets, but because of their internal strategies.

However, the literatures also show that FDIs expand the outreach of such multinational companies, for instance, by expanding their markets. This way, companies improve their profitability and market networks (Murphy 2008).

The California-based technology company may similarly take advantage of such opportunities to expand its core market base and eventually improve its operations by expanding its activities beyond California.

According to Akhter (2011), limiting the company’s activities within California is an old strategy that past companies adopted to maintain a strong market position in their home markets.

For example, companies used to establish semi-autonomous positions in several industries within their home markets to maintain strong market dominance over similar companies operating in the same market.

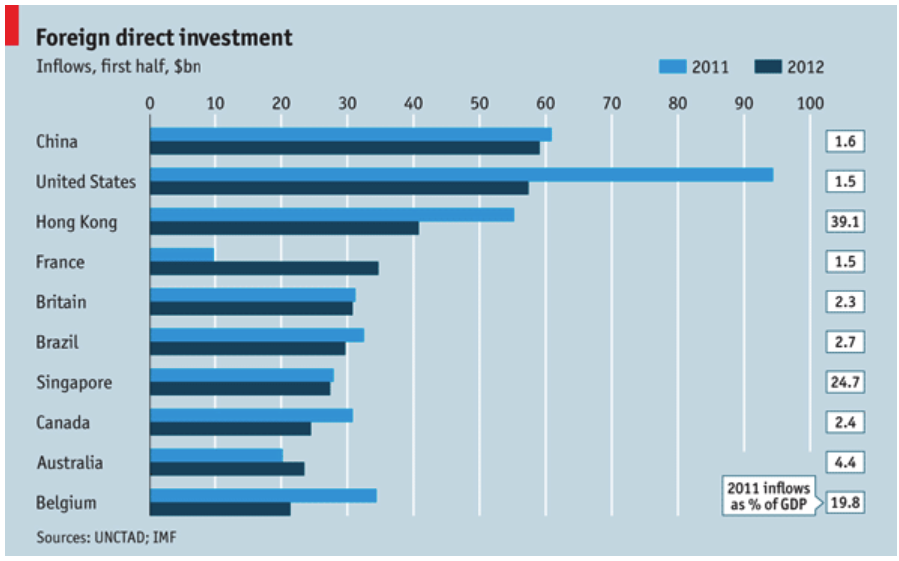

For a long time, America has been the greatest beneficiary of the global FDI. However, with the changing economic policies of different countries, and the persistent economic problems facing developed nations, China has overtaken America as the biggest recipient of global FDI.

Globally, FDI is decreasing. In fact, the U.N. conference on trade and development recently said it reduced its forecast for FDI in 2012 by about $1.6 trillion (The Economist 2012). FDI into wealthy countries decrease annually, but FDI into developing countries increases every year.

The Economist (2012) says that currently, developing countries account for more than half of the world’s FDI. The chart below shows the changing trends of FDI worldwide.

As observed from the above diagram, China leads in foreign direct investment worldwide. Through these FDIs, companies may increase their markets and expand their operations worldwide. These investments improve their operational efficiencies and increase their profitability.

Outsourcing

“More than 75% of the world’s 2,000 largest companies are engaged in offshore outsourcing” (Weier 2007, p. 1). This is a statement made by Weier (2007) to show the extent of off shoring activities in the global marketplace. He also believes that the number of companies engaged in outsourcing activities may rise to about 40% in the next decade.

The main driver pushing multinational companies to engage in outsourcing is the opportunity to save costs. However, as companies continue to rely on their overseas markets for revenue growth, many managers are re-evaluating where they think it is economically sustainable to place their employees (Flatworld Solutions 2012, p. 1).

Many I.T. companies are expanding their information technology operations into overseas markets (notably India, China, and other parts of Asia). The California-based technology company similarly needs to follow the same trend because there are several advantages that the company could derive from this strategy.

Besides the cost advantages associated with outsourcing, the company may similarly obtain high-quality services to improve its core operations. Complementarily, as the company expands its operations, it may benefit from outsourcing by focusing on its core business activities (Bucki 2012, p. 1).

For example, in a rapidly expanding growth period, the company may experience an increase in its back-office operations, which may compromise the core business services that helped the business rise in the first place.

It is, therefore, wise to outsource some of these back-office operations in overseas markets so that the company concentrates on its core business services. This way, the company may maintain its profitability and competitive advantage in the future.

Comparative Advantage

If the California-based Technology Company intends to distribute its activities across the globe, it may face stiff competition from other companies in the international market. The importance of the comparative advantage theory surfaces in this regard.

The comparative advantage theory complements the need to have a robust global technology strategy to elevate the company to global competitiveness. Specifically, the theory explains why the company needs to re-invent itself in the global market.

The comparative advantage theory refers to a country’s ability to produce goods and services at relatively lower costs than its competitors do (Goel 2009). Usually, marginal and opportunity costs establish the level of comparative advantage that an organisation (or country) has over another.

This theory largely explains the differences in international trade by demonstrating how different countries benefit from trade (even if one country produces a bulk of the goods or services). Usually, the gains derived from such international transactions become the ‘gains of the trade’ (Maneschi 1998).

The law of comparative advantage, which stipulates the importance of countries to sustain their comparative advantage by re-inventing themselves in the global market, demonstrates the importance of the comparative advantage theory (Goel 2009). Particularly, this understanding closely refers to the need for the California-based technology company to distribute its activities in the international market because the company may easily sustain its comparative advantage by re-inventing itself in the international market.

This relationship explains the association between the comparative advantage theory and globalisation because globalisation also encourages companies to penetrate new markets through globalisation.

Analysts draw close similarities between globalisation and the comparative advantage theory because companies sustain their comparative advantages by re-inventing themselves on the global map (Goel 2009).

Furthermore, experts draw a strong link between globalisation and its ability to increase a company’s operational efficiencies.

After carefully scrutinising the structure and concepts of the comparative advantage theory, we see that the theory encourages companies to operate as if there were no international barriers to trade (Maneschi 1998).

Conversely, if this theory applied to the California-based technology company, the comparative advantage theory would stipulate that the Californian Company should expand without succumbing to the barriers of trade.

Practically, it is difficult to defend this philosophy because there are substantial barriers to trade on the international market. For example, some countries still have protectionist policies that act as impediments to international trade.

These impediments highlight the difficulties that the company may face as it ventures into the international market (for instance, the dominance of other technology companies pose a barrier to the entry of foreign companies).

Furthermore, different countries have different economic environments that pose varied dynamics of international trade. Some of these dynamics are unfavourable to international trade (Goel, 2009).

Besides the challenges of having a complementary economic environment, critics of the comparative advantage theory say that even if the theory is applied effortlessly, so companies that have a stronger comparative advantage produce goods and services (instead of companies that do not share this advantage), the flow of capital is not going to be equitable (Maneschi 1998).

This observation contradicts suggestions advanced by proponents of globalisation who show that international trade is a zero-sum game where everybody benefits equally. Equitable capital distribution only occurs in perfect markets, but perfect markets do not exist. This criticism forms part of the challenges of distributing the company’s activities across Europe, Asia, and the U.S.

Conclusion

Like many social and economic issues, globalisation may polarise societies. Indeed, globalisation has its pros and cons.

The suitability of globalisation to different company contexts, however, forms the basis for this study and as many successful technology companies do, this paper proposes that embracing globalisation is the best strategy for the Californian-based company.

The company may enjoy the many advantages of this strategy, including comparative advantages, cooperative advantages, competitive advantages, and value addition (Khilji 2005).

Maintaining the company operations in California helps to avoid some of the pitfalls of globalisation (like the depreciation of currency value, loss of corporate values, and changing consumer behaviours), but the benefits derived from globalisation transcend some of these key challenges.

In fact, this paper demonstrates that globalisation accommodates some of society’s different dynamics, such as, cultural differences. There are, therefore, minimal arguments that oppose the decision to distribute the company’s operations across different geographic regions.

Through this understanding, this paper proposes that the California-based company should embrace globalisation by distributing its activities across Europe, Asia, and America.

References

Akhter, S. 2011, ‘An empirical note on regionalization and globalization’, Multinational Business Review, vol. 19 no. 1, pp. 26 – 35.

Akisik, O. 2009, ‘Globalization, US foreign investments and accounting standards’, Review of Accounting and Finance, vol. 8 no. 1, pp. 5 – 37.

Alvarez, M. 2010, ‘Istanbul as a world city: a cultural perspective’, International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, vol. 4 no. 3, pp. 266 – 276.

Bobek, V. 2005, ‘The signification and the feasibility of measuring globalization of economy’, Industrial Management & Data Systems, vol. 105 no. 5, pp. 596 – 612.

Britt, D. 2007, Impact of Globalization in Creating Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Web.

Bucki, J. 2012, Top 7 Outsourcing Advantages. Web.

David, P. 2010, International Logistics the Management of International Trade Operations, Cengage Learning, London.

Estrin, S .2012, Foreign direct investment in transition economies: Strengthening the gains from integration. Web.

Flatworld Solutions 2012, Benefits of Outsourcing. Web.

Goel, D. 2009, Theory of Competitive Advantage. Web.

Goodman, M. 2005, ‘Restoring trust in American business: the struggle to change perception’, Journal of Business Strategy, vol. 26 no. 4, pp. 29 – 37.

Hamel, G. 2012, How Do Currency Rates Affect the Markets?. Web.

Harney, S. 2006, ‘Regulation and freedom in global business education’, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, vol. 26 no. 3/4, pp. 97 – 109.

Iqbal M. 2006, ‘Globalization at crossroads of warfare, revolution, and universalization: The Islamic panacea, stratagem and policy instruments’, Humanomics, vol. 22 no. 3, pp. 162 – 177.

Johnson, R. 2011, The value-added content of trade. Web.

Khilji, T. 2005, ‘Why Globalization Works’, Journal of Economic Studies, vol. 32 no. 3, pp. 294 – 296.

Maneschi, A. 1998, Comparative Advantage in International Trade: A Historical Perspective Edward, Elgar Publishing, London.

McLaughlin, C. 1996, ‘Strategies for globalizing service operations’, International Journal of Service Industry Management, vol. 7 no. 4, pp. 43 – 57.

McPhee, W. 2006, ‘Making the case for the added-value chain’, Strategy & Leadership, vol. 34 no. 4, pp. 39 – 46.

Mraovic, B. 2010, ‘The geopolitics of currencies and the issue of monetary sovereignty’, Social Responsibility Journal, vol. 6 no. 2, pp. 183 – 196.

Mr Globalization 2011, Nationalism and globalization. Web.

Murphy, J. 2008, ‘Management in emerging economies: modern but not too modern’, Critical perspectives on international business, vol. 4 no. 4, pp. 410 – 421.

Pakravan, K. 2011, ‘Global financial architecture, global imbalances and the future of the dollar in a post-crisis world’, Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, vol. 19 no. 1, pp. 18 – 32.

Prestowitz, C. 2012, Apple has an obligation to help solve America’s problems. Web.

Shaw, C. 2005, Building Great Customer Experiences, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Sintonen, T. 2002, ‘Racism and ethics in the globalized business world’, International Journal of Social Economics, vol. 29 no. 11, pp. 849 – 860.

Steingard, D. 1995, ‘Challenging the juggernaut of globalization: a manifesto for academic praxis’, Journal of Organizational Change Management, vol. 8 no. 4, pp. 30 – 54.

Study Mode 2013, Extent of Globalisation. Web.

The Economist 2012, Foreign direct investment. Web.

Vaccaro, V. 2009, ‘B2B green marketing and innovation theory for competitive advantage’, Journal of Systems and Information Technology, vol. 11 no. 4, pp. 315 – 330.

Volkman, R. 2006, ‘Dynamic traditions: why globalization does not mean homogenization’, Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, vol. 4 no. 3, pp. 145 – 154.

Weier, M. 2007, The Second Decade Of Offshore Outsourcing: Where We’re Headed. Web.

Zanfei, A. 2005, ‘Globalization at bay? Multinational growth and technology spillover’, Critical perspectives on international business, vol. 1 no. 1, pp. 5 – 17.