Article Summary

The subsidy of public goods by government

According to Johnson and Whitehead (2001) article titled “the subsidy of public goods by government”, the rush to build arenas and sports stadiums were witnessed in the 1990s. Most governments opted to subsidize the cost of constructing both stadiums as well as arenas to facilitate their respective utilization by professional players.

The claim to subsidize such projects was based on the justification that the projects would create positive externalities and preciously demanded public goods. However, measuring benefits accruing from the projects proved to be a daunting task. The total expenses incurred on the completed projects in addition to the decade planned expenses totaled to $9 billion. The local governments in conjunction with the state provided over 80% of the total funding.

In 950s, the stadium construction boom trend had initiated. In fact, a majority of key sports clubs including sixteen baseball teams were playing in privately held buildings. In 1989, most football, hockey, baseball and basket teams enjoyed playing in publicly held stadiums. Even though building the arenas and sports stadiums became trendy and similarly admired amongst various states alongside local governments, the projects have not confirmed their financial worthwhile.

Researchers such as Fort and Quirk (1992) showed in the publication that most sports buildings that were publicly funded failed to perpetually produce enough income to enable the proprietors cover the overall opportunity costs (Johnson & Whitehead, 2001). Actually, more failures became eminent when the return on the deemed viable investments could not cover the operational variable costs.

The article thus reported the application of a valuation technique dubbed as contingent valuation method which was used to determine the produced worth of two of public goods ensuing from two recommended projects in Kentucky. The two projects included a league baseball stadium and a novel basketball arena.

Neither of the proposed projects could satisfactorily produce publicly demanded goods to vindicate the initiated government or public financing. While the outcomes could not be generalized, they helped in shading light on certain major issues that were involved by demonstrating the viability of applying the above named technique to assess subsidized stadiums (Johnson & Whitehead, 2001).

The impact of government subsidy on the supply and demand of commodities

Governments have opted to build several arenas and stadiums to attract new teams and prevent the exit of the already existing teams. Advocates of public sports ground and stadiums argue that positive externalities that accrue from teams and stadiums make it possible for the generated benefits to surpass the incurred costs.

However, since most benefits emanate from the externalities, there are no hopes that savvy private investors generate ample gain to validate the construction of a stadium. Therefore, if the governments fail to subsidize the construction of stadiums and other public sports grounds, then a state, a city or even a nation would be worse off by loosing their teams as a consequence.

Basically, there are two kinds benefits that sports teams create as a result of ensuing positive externalities. These include the direct benefits and indirect benefits (Gwartney et al., 2010). The direct benefits that teams generate come as a result of the production of public goods from the participating teams.

The notable public goods and services created are both non-rivalry as well as non-excludable and they include fans loyalty, the public spirit and civic pride. All these exist because of the teams’ presence. Through subsidizing the cost of constructing stadiums, the accruing public goods and services will increase while the general public will endlessly share their triumph hopes, exult in team’s victory, and talk about their adored teams.

Since the community will be drawn together and determination will be shared, the demand for such sporting facilities will increase (Mankiw, 2011). Moreover, given that the cultural importance of sports will increase and thus exceeding the economic significance of the perceived business,

the governments will be forced to subsidize the construction of more stadiums since the accruing external benefits surpass the incurred costs. Hence, through subsidizing the construction of stadiums, the government will increase the demand for such sporting facilities.

When subsidy plans are implemented, the supply of sports ground and stadiums will also increase thus increasing the indirect benefits which will be in form of aggregate income. For example, if more tourists are drawn by the newly constructed stadiums, the production town hotel and restaurant services, meals, and various other income generating activities will increase.

By means of the multiplier effect, tourists’ activities and services offered in such towns will generate more income. A great deal of the generated income will nevertheless accrue to the operating companies and local firms as instead of the participating teams (Gwartney et al., 2010).

The demand and supply graphs

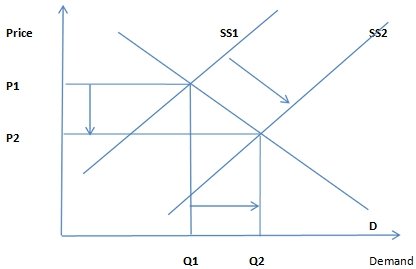

The change resulting from government subsidy

A subsidy basically implies that the government off sets part of the total cost that could have been incurred by the consumers on certain publics commodities (Gwartney et al., 2010). For example, when the governments of various countries decide to pay part of the total cost incurred in building stadiums, more stadiums will be built.

The resulting effect will be a positive shift in the supply curve (ss) from the original SS1 to SS2. This will in return result into lower public goods prices while the quantity demanded will increase. See the diagram below for the expected changes resulting from government subsidies.

Government Subsidy Diagram

Government subsidy causes a rightward shift in the supply curve from SS1 to SS2 and increases quantity demanded from Q1 to Q2. However, the generated revenue decreases as a result of a decrease in price levels from P1 to P2.

References

Gwartney, J. D., Stroup, R. L., Sobel, R., S. & MacPherson, D. (2010). Macroeconomics: Private and Public Choice. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Johnson, B., K. & Whitehead, J., C. (2001). Value of public goods from sports stadiums: The CVM approach. Contemporary Economic Policy. Web.

Mankiw, N., G. (2011). Principles of macroeconomics. Mason, OH: South-Western, Cengage Learning.