Introduction

Greco-Roman antiquity is a bright page in the history of civilization, representing a mixture of knowledge, ideas, traditions, and customs that were formed from the fusion of the Greek and Roman peoples. When the Romans conquered Greece and began assimilating local culture, well-educated Roman citizens learned Greek and interacted with the newly conquered culture. It was not just a copy of the Greek and Hellenistic models, because as a result of the merger, a completely new, unique culture was formed. This new cultural model influenced all spheres of public life, including such a broad topic as the naming traditions in ancient Rome.

Names during the Republic Period

In the era of the Republic and later, the Romans bore three names. Praenomen corresponds to our familiar names: Marcus, Gaius, Lucius, etc. Nomen gentilicium indicates the clan to which a person belongs: it is something like our surname, but in a broader sense, it includes many other families and sometimes extends to thousands of people (genus – gens). Cognomen is a nickname that indicates any character trait or appearance of a person. For example, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa is a common Roman nomenclature (Diazilla, 2022). According to Rizakis (2019), traditional Greek names express the individuality of their owners. However, from the 2nd century BC, i.e., after the conquest of Greece by Rome, many noble Greeks began to use the Roman nomenclature in official honorific documents. Nevertheless, the Greek nobility still managed to apply their traditions to the Roman nomenclature (Kantola & Nuorluoto, 2022). Moreover, the Greeks continued to use their usual single names – praenomen in an informal context.

Slave Names and the Influence of Christianity

As in Greece, slaves could keep the names at birth in Rome. More often, however, slaves were distinguished by their origin in homes and estates, and then the ethnicon replaced the personal name: Sir, Gallus, etc. Enslaved people were often called puer – a boy – combining this designation with the name of the master in the genitive case (Lewis, 2018). Thus, the slave of Marcus became Marziporus, and the slave of Publius became Publiporus. Christianity, trying to break away from the pagan tradition of names, decisively introduced into the nomenclature unusual, artificially created, and sometimes quite bizarre constructions based on Christian ritual formulas or prayers. Here are some examples: Adeodata is “God-given,” Deogratias is “thanksgiving to God,” and even Kvodvultdeus is “what God wants.” Partly influenced by Christianity from the 3rd century AD, a new naming system emerged in ancient Rome – just a single name, Greek or Latin (Rizakis, 2019). Therefore, Christianity particularly caused the change of the usual Roman naming system.

Roman Names of the Late Empire

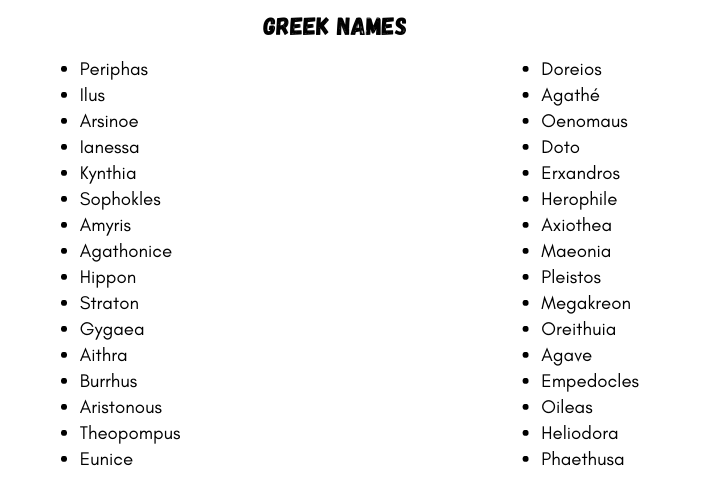

By the middle of the 1st millennium AD, the previously most common tria nomina gradually lost its relevance and was replaced by simple names following the example of the Greek ones. Thus, common Greek first names, like Agathe or Kynthia, were returned to use (Bilal, 2022). Kantola and Nuorluoto (2022) claim that by the time of the conquest of Rome by the barbarians, the triple nomenclature had been preserved only by representatives of the noblest families. However, parts of the names used in tria nomina have survived to the present day in a modified form and are still in use nowadays.

Conclusion

Throughout Antiquity, in different periods, there was the dominance of both the Roman naming system and the Greek one. In the end, it was the Greek model that was the winner. Most likely, this happened because of the greater convenience of using the double nomenclature compared to its competitor. However, the triple system is still preserved in some Eastern European countries, although it differs from the one used in ancient Rome.

References

Bilal, M. (n.d.).Greek names [Online image]. Greek names: 190+ ancient and classical Greek warrior names.

Diazilla. (n.d.). 8 Conferenza I classico (tria nomina)[Online image].

Kantola U., Nuorluoto T. (2022). Names and identities of Greek elites with Roman citizenship. In C. Krötzl, K. Mustakallio & M. Tamminen (Eds.), Negotiation, collaboration and conflict in ancient and medieval communities (pp. 20-26). Routledge.

Lewis, D. M. (2018). Greek slave systems in their Eastern Mediterranean context, c.800-146 BC. OUP Oxford.

Rizakis, A. (2019). New identities in the Greco-Roman East: cultural and legal implications of the use of Roman names. Proceedings of the British Academy, 237-57. Web.