- Background of Greece

- Background of Ireland

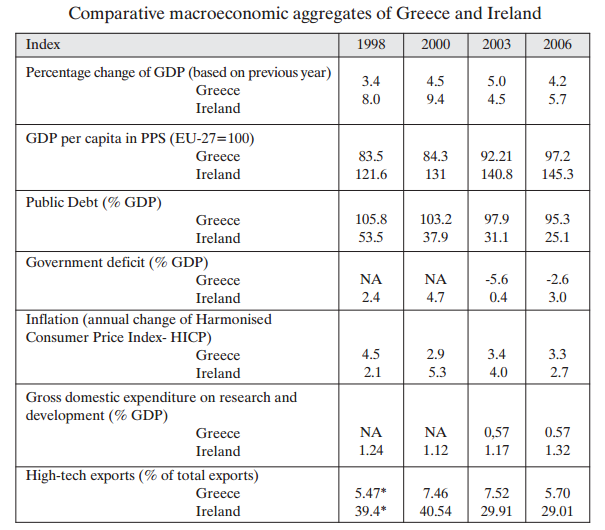

- Comparing the Macroeconomic Figures between the Two Nations

- Consequences of Bretton Woods on Greece and Ireland

- Dealing With the European Debt Crisis

- Role of Government in Achieving a Stable Financial Market

- Future Stance of Greece and Ireland

- The Way Forward for Greece

- Conclusion

- References

Background of Greece

Greece joined the European Union (EU) in 1981. During its early days in the EU, the Gross Domestic Product per capita (GDP) was 7.2555 dollars. Due to its low GDP, it joined the Cohesion Fund where a review on its economic progress was done in 2003 (Magoulios & George 2013). It was later disqualified from the Cohesion Fund. Instead, it joined a policy. Between 1960 and 1973, an imbalance in the labor market was blamed for their failing economies (Magoulios & George 2013). Greece’s geographical location is blamed for its low development rates. In essence, it is situated far from the European countries whose economies are performing well. The implementation of new technology in the Greek industry has also been at a slow pace, leading to a dawdling industrial growth.

Background of Ireland

Ireland joined the EU in 1973. When joining the EU, its GDP was 6.199 dollars. Before being a member of the European Union (EU), Ireland depended greatly on agriculture. Consequently, the EU introduced low corporate taxes and established an Industrial Development Agency (IDA Ireland). This body placed Ireland back on the global index of flourishing economies. Ireland has a small economy that is influenced by world markets and international trade.

Greece and Ireland had similar economic status. However, the growth in Ireland was more than that in Greece. The European Commission (EC) tracked the economic growth to the increased investment and fiscal consolidation. Fiscal consolidation refers to the steps taken by a government to reduce the amount of debt and deficits. According to Magoulios and George (2013), the Foreign Direct Investment in Ireland (FDI) led to an increase in companies, financial services, and employment opportunities.

Comparing the Macroeconomic Figures between the Two Nations

Governance between the two countries has differed considerably in recent times. For Greece, it was engaged in fighting a runaway debt since the 1990s (Taylor 2015). After 210, the government began borrowing sporadically again due to the availability of international funds. This situation saw the country fall deeper into debt. For Ireland, the government was tasked with proving to international investors and EU partners that it was not spending money irresponsibly. As a reason, the Irish government engaged in reduced spending to attract potential investors (FDI).

Magoulios and George (2011) have made a side-by-side comparison of the macroeconomic features of the two cohesion nations. Ireland demonstrates performance that is superior to that of Greece’s based on most indicators: GDP growth (except 2003), GDP per capita, deficit, and public debt(See Table 1). Regarding inflation, Greece experienced a lower index in 2000, but a higher one in 1998 and 2006 (Magoulios & George 2011).

Taylor (2015) observes that Ireland has a lower debt compared to Greece. When the crisis hit in 2008, Greece’s debt was already at 100% of the country’s GDP, predisposing the country to further debt that reached danger levels (Taylor 2015). Despite the already existing debt, Greece continued borrowing due to the availability of international funds. On the other hand, as of 2016, Ireland has improved considerably from its debt crisis while Greece has continued to plunge deeper into debt. Taylor (2015) observes that Ireland maximized the bailout funds extended to the country by the EU, thus cutting down its debt considerably.

Both countries were engaged in severe austerity programs. Wren-Lewis (2015) observes that Ireland succeeded in turning around its debt to the extent of gradually increasing international trading confidence. However, due to how austerity programs are designed to work, the country experienced an increase in unemployment (Wren-Lewis 2015). For the same period, Greece had higher employment and value-added rates within the primary sector.

However, Ireland responded faster relative to Ireland, thus resulting in a value-added industry that was twice that of Greece (Magoulios & Exarchos 2011). Magoulios and Exarchos (2011) observe that Greece’s value-added share, as well as unemployment, outweighed Irish regarding the tertiary sector(transport, communications, and trade).In 2003, Greece’s annual productivity per worker [EU =100] was at 97.8% while it stood at 129.2%for Ireland. The overall productivity of the economy of Greece was 87.3% while the same for Ireland stood at 121.1% (Magoulios & George 2011).

In recent times, investors have expressed concerns that Ireland could be the next Greece (Ross 2016). However, Ireland has attempted to adjust its government spending to retain investors. Additional efforts included rescuing banks that were on the verge of collapsing and raising domestic taxes. These actions were part of the country’s wider austerity program. Critics such as Ross (2016) argue that poor people have not benefited, despite the economic recovery. Greece’s debt-to-GDP has been on a steep rise since 2007 when it was just 103%. At the end of 2015, it stood at 176.9%.

All EU countries share a common monetary policy. Taylor (2015) argues that the current monetary policy has not augured well with the weaker economies. Under this EU monetary policy, the Euro is overvalued by 20%, which has served to raise Greece’s inflation even further (Taylor 2015). In contrast, Ireland has fared well, despite the possible inflation caused by the overvaluation of the Euro (Taylor 2015). Regarding foreign exchange (fx), both countries have different approaches. Greece’s fx is fixed. In contrast, Ireland’s fx is flexible (managed), a situation that allows a higher volume of foreign direct investment into the country (Soetendorp 2014).

Consequences of Bretton Woods on Greece and Ireland

The efforts to restore the financial system of Greece led to it joining the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in 1953. Coupled with joining the Bretton Woods, it also liberalized its imports and exports, improved its fiscal policy, abolished systems of market control, and/or improved the public investment program. Thus, the public’s confidence in the national currency was restored due to the developments. After joining the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rates system, the Greek economy registered a 7.9% growth rate (Argitis & Michopoulou 2012). This figure was the second-highest ever-recorded growth rate in OECD countries.

Later, Greek’s economy suffered heavily from the disintegration of Bretton Woods. According to Argitis and Michopoulou (2012), high inflation rates led the bank of Greece to erect quantitative limits on the loans given to the public. The disintegration of the Bretton Woods system of exchange rates led to Ireland joining the European Monetary System (EMS) in 1979. Through EMS, all currencies used the Deutschmark as an anchoring point. The result was the decreasing inflation rates in Ireland (Rao, Tamazian, & Kumar 2010).

Dealing With the European Debt Crisis

Ireland is often given as an example when demonstrating how successful an austerity program can become. A country under an austerity program is supposed to adopt certain conditions, as required by the EU. Ireland had to reduce government spending, a strategy that reveals why unemployment rose by 2.7% between 2009 and 2012 (Taylor2015). A reduction in government spending in Ireland led to unemployment, accompanied by reduced prices and wages.

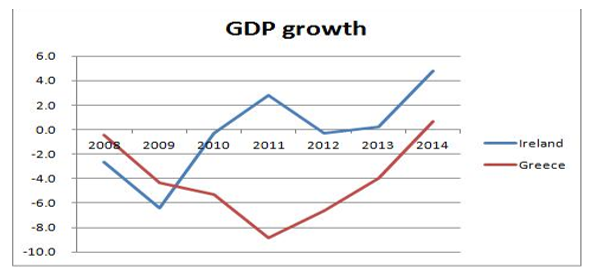

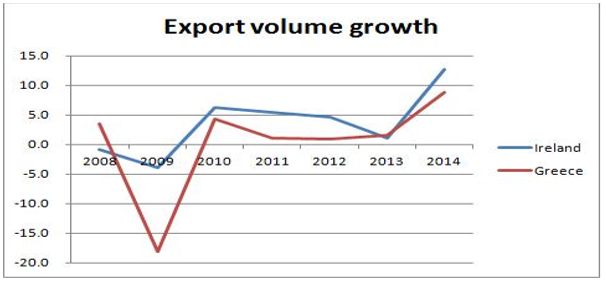

Ireland’s current strong growth and falling unemployment reflect the successful application of the austerity program. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) places Ireland’s growth in 2014 at 5%, which can be largely attributed to the 12% increase in the volume of exports (Wren-Lewis 2015). Despite a similar austerity program being extended to Greece, the country was unable to step out of its debt crisis. Figure 1 below is an illustration of the two countries’ economic growth [Data from OECD’s Economic Outlook). While the 2009 recession affected most countries, the experience was bad for Ireland but even worse for Greece.

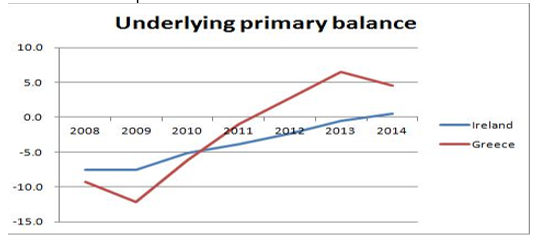

The question that arises is, ‘why did Greece fail to recover from the debt crisis?’ Wren-Lewis (2015) argues that the reason for Greece’s failure to rise above the crisis can be attributed to the fact that the country was subjected to more austerity. Figure 2 below indicates that the fiscal contraction for years 2009-2013 was 2.7 times greater in Greece when compared to Ireland.

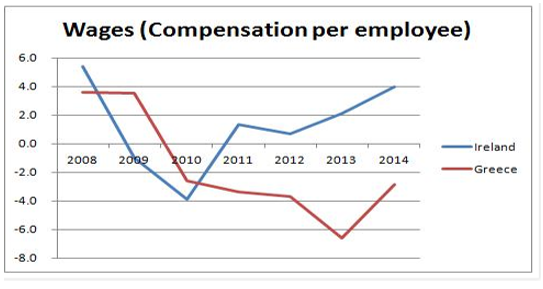

While this measure is not ideal since the effect of tax can be eased, the figures representing government spending [OECD data] reflect a similar trend. As shown in Figure 3, both cases reveal an ‘internal devaluation’, as it was observed in the case of Ireland. Therefore, Greece experienced a similar fall in wages and prices, as the Irish experienced it.

Figure 4 indicates a comparison of the export volumes between Greece and Ireland. Ireland indicates a massive increase in the volumes of exports while they remained much the same for Greece. The small volume of exports by Greece may partly explain the anomaly concerning Ireland’s growth, even though both countries applied for similar austerity programs.

Greece exports much less than is expected, considering the ‘gravity’ model, which economists rely on to determine a nation’s export capacity. According to Böwer, Michou, and Ungerer (2014), Greece controls 16% of the world’s shipping industry, thus placing the nation in a great position to export its products. However, the country has not been keen to focus on this advantage. This situation portrays an institutional weakness. Additionally, Ireland is a more open economy compared to Greece, meaning that the former receives more foreign direct investment relative to the latter.

Role of Government in Achieving a Stable Financial Market

Ireland has been engaged in a strategy that aims at a gradual exit from the EU-IMF of financial aid. The country has been keen on recovering from the financial crisis that had bedeviled its economy for nearly a decade. Stull (2014) observes that part of Ireland’s efforts to attain a debt-free economy includes restructuring the country’s bank sector. This plan is expected to rebuild trust in Ireland’s banks, hence strengthening its position in disseminating financial services. Debt restructuring is another approach that is aimed at helping insolvent companies that have prospects of future survival (Stull 2014). The government has also enacted the Irish Strategic Investment Fund (ISIF), a law aimed at increasing the finances that are directed toward SMEs.

Greece for its part has increased the role of its central bank to safeguard depositors and/or protect the economy from a further crisis (Stournaras 2016). In 2008, a law was passed that allowed capital to be extended to Greek banks, as well as allowing the banks to issue government-guaranteed bonds. These bonds are then used in refinancing operations. The government has also put in place provisions that are aimed at preventing liquidity problems from turning into solvency problems (Stournaras 2016).

Future Stance of Greece and Ireland

Greece’s economy is projected to improve after the recession that affected its financial systems. Analysts track it to the reduction in political turmoil and a growing tourism sector. The high unemployment cases are expected to reduce. The low investment and lack of confidence from the public have been tracked down to high public debt. The government projects a reduction in poverty and inequality after the implementation of the Guaranteed Minimum Income policy (Stournaras 2016). Barriers to the competition are likely to be removed in a bid to spur growth. After the release of the 2017 budget plan, Greece is set for economic growth as it recovers from the seven-year economic slump.

After its recovery from the financial crisis, Ireland is expected to continue registering economic growth. Domestic industries will improve, and hence the expected increase in the rate of employment. As the labor market tightens, the wage rates will receive a boost. The government’s goal of maintaining a balanced budget will remain on track while relying on the growth of revenues and low-interest costs. The government is expected to employ structural reforms in a bid to get people back to formal employment. The public is not well-informed on Knowledge-Based-Capital (KBC) investment, a situation that has led to low productivity levels (Morgenroth 2010). However, the increase in the use of KBC by multinationals is likely to increase productivity rates countrywide.

The Way Forward for Greece

Greece has invested in research and development to strengthen its industries. Through research and development, the country has innovated high-value products that will sell in the international market. The quality of human capital has also been strengthened to improve the economy. There is harmony in the research institutions in collaboration with the government. Government funding has greatly improved the ability of research institutions to carry out explorations.

Local support structures for SMEs are also built and developed in line with the research and development agenda (Magoulios & George 2011). Employment subsidies are directed to the youths who are most disadvantaged. Legislation on employment protection is at the infancy stage to abolish dualism. Dualism should be replaced with single contracts with fewer possibilities of dismissal (Magoulios & George 2011). Consequently, the minimum wage will attract the public to joining formal employment.

Conclusion

Greece and Ireland are categorized among the poorest members of the European Union, referred to as the cohesion nations. After the 2008 economic recession, the EU extended funds to the two countries to help the recovery of their economies. In return, the two governments were required to enforce austerity measures to reduce government spending. However, critics of the success of the Eurozone austerity in Ireland have argued that the economic spur does not resonate with the poor citizens.

Hence, despite the recovery from debt, low-income Irish people are still living in poverty. This observation indicates a low HDI. Nevertheless, unemployment rates in Ireland have dropped greatly, pointing to a promising future. In contrast, Greece continues to experience high unemployment rates and poverty by citizens. Therefore, Greece’s HDI is reflective of the country’s public debt. Greece can benefit from adopting Ireland’s approach to the austerity program.

References

Argitis, G & Michopoulou, S 2012, Financialization and the Greek Financial System, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece, Athens.

Böwer, U, Michou, V & Ungerer, C 2014, ‘The puzzle of the missing Greek exports’, Economic papers, vol. 518, no. 1, pp. 1-40.

Magoulios, G & George, E 2011, Α Comparative Analysis between the Economies of Greece and Ireland, University of Piraeus, Greece, Athens.

Morgenroth, E 2010, ‘Exploring the economic geography of Ireland’, Journal of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 42-74.

Rao, B, Tamazian, A & Kumar, S 2010, ‘Systems GMM estimates of the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle for the OECD countries and tests for structural breaks’, Economic Modeling, vol. 27, no. 5, pp.1269-1273.

Ross, S 2016, Ireland economics: 3 troubling similarities to Greece. Web.

Soetendorp, B 2014, Foreign Policy in the European Union: History, Theory & Practice. Routledge, London.

Stournaras, Y 2016, The impact of the Greek sovereign crisis on the banking sector: challenges to financial stability and policy responses by the Bank of Greece, University of Piraeus, Greece, Athens.

Stull, G 2014, ‘Future Directions for the Irish Economy: Conference Proceedings’, Economic Papers, vol. 524, no. 1, pp. 1-112.

Taylor, C 2015, Cliff Taylor: A tale of two economies – could Greece learn from Ireland? Web.

Wren-Lewis, S 2015, Ireland and Greece. Web.