Introduction

Concrete compressive strength testing is used to establish the characteristics of specimens when subjected to a weighing load. The strength is measured in N/mm2 or MPa. In most cases, such strengths are dependent upon the quantity and type of cement used in the concrete mix. The compressive stress of hardened cement is the most significant of all the characteristics. Therefore, cement is often verified for its strength in the laboratory before it is used in vital construction works. Specimens tested are usually cuboidal or cylindrical geometries in nature. Compressive strength is dependent on the water-cement ratio (WCR), mixing technique, placing, and curing. Strength tests are not made on neat cement paste because of difficulties of the excessive shrinkage and subsequent cracking of neat cement.

The general objective of this testing is to evaluate the reliability and protection of the constituents used to make the specimen. Materials used in load-bearing applications with strong compressive forces must have high structural integrity. The formula for compressive strength is the force exerted divided by the specimen’s cross-sectional area. Consequently, the specimen is likely to have low compressive strength to withstand high pressure. Therefore, the specific objectives for the laboratory experiment include three tests. First, test 7-days old cement pastes cubes in compression using 2-in cement paste cubes with varying WCRs (0.30, 0.50, and 0.70). Second, to test the 7-days old “small” concrete cylinders in compression using 2-in diameter concrete cylinders with varying WCRs (0.30, 0.50, and 0.70) using the hydraulic machine. The last objective was to test the 90-days old “large” three 4×8 concrete cylinders in compression, which had a WCR of 0.40.

Material and Methods

Materials

- Three each cuboidal or cylindrical Portland cement

- Water

- Weighing balance

- Glass cylinder

- “Small” concrete cylinders Cube mold (2” x 2” x 2”)

Pre-Labs Steps

- Upon the preparation of mix from the previous laboratory tests, the required number of molds sufficient to make 3 cuboidal and 3 “small” cylindrical ones were filled. Three 90-days old “large” three 4×8 concrete cylinders were also obtained from the laboratory test of a previous laboratory test. The tamping pressure was then established sufficient enough to guarantee uniform filling of the molds.

- After completion of the filling, the molds were placed in moist air for 24 hours and later placed underwater for 7 days.

Procedure

- After completion of the curing period (7 days), the specimen was taken out from the water and kept in the air to ensure that the surfaces were dry and free from water.

- The bearing surface of the testing machine was then cleaned.

- Weighing loads were then applied to the specimen faces that are in contact with the plane surfaces of the mold.

- The specimens were placed in a testing machine below the center of the upper bearing block.

- The movable parts of the bearing were then rotated gently by hand so that it touches the top surface of the specimen.

- The total maximum loads specified by the testing machine were recorded and the comprehensive strengths were calculated in pounds per square inch. (The load were applied with the rate in the range of 200-400 lbs/s) with careful noting of any unfamiliar features in the type of failure.

Results

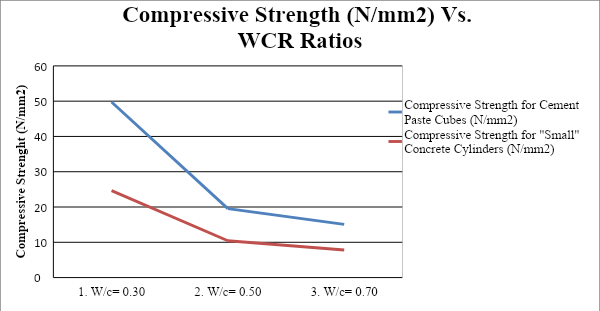

After completing the compressive testing for the concrete cubes on day 7 from curing of the concrete in the moisture room, compression testing data from the different WCRs were used and combined with current data to generate tables (Table 1-4) and the line graphs (see Figure 1). Appendix 1 also designates the sample results of the cubes and cylinders upon compression up to the maximum load before failure. The graph was used to identify the existence of an association between the maximum load of the mix designs and the water-cement ratio of the cement paste cubes, “small” concrete cylinders, and “large” concrete cylinders.

Table 1. Dimensions and maximum load for cement paste cubes and “small” concrete cylinders.

Table 2. Dimensions and maximum load for “large” concrete cylinder

Based on the data provided in Tables 1 and 2, the following compressive strengths were obtained using the following formula:

Compressive strengths= Load (N)/ Dimensions Area (mm2).

Table 3. Compressive Strengths for Cement Paste Cubes and “Small” Concrete Cylinders

Table 4. Compressive Strengths for “Large” Concrete Cylinders

From Table 3 above, the following graph was obtained as shown in Figure 1 below.

Table 5: The Average, Standard deviation, and Coefficient of Variation of Compressive Strengths of the “large” Concrete Cylinders

Discussion

Concrete dependability and performance for construction work depend on such factors as the shape of the concrete used, WCR ratio, and the number of days the cement takes to cure. For instance, concrete is a substance, which can be cast in many attractive shapes and various forms. However, the durability of such construction material depends on the compressive strength. Compressive strength plays an essential function in the stability of structures. From the above data (see Figure 1), the WCR is inversely correlated with the strength of concrete. In this case, if the WCR ratio increases then the strength decreases and vice versa. When the WCR is low, the cement is probably containing unhydrated cement particles that remain within it. For this reason, the lower the WCR the lower it can gain water after the first 7 days, thus the higher compressive strength.

The effect of the WCR ratio is different for various concrete shapes. For instance, as shown in (see Figure 1), the compressive strength for cement paste cubes is higher than the compressive strength for “small” concrete cylinders. According to Qasim (2018), the compressive strength of concrete cylinders is lower than the compressive strength of concrete cubes of the same WCR ratio and belonging to the same curing period. In the experimentation of cube and cylinder shapes, the molds are influenced by parallel stresses all through their length compared to the cylinder which has an unaffected focal area that is unaffected by parallel stresses. In this sense, the experimental data is in agreement with the standard situations based on scientific research. According to Qasim (2018), the strength of the cube of the controlled specimen will be different from the standard strength of the cylinder. However, Talaat et al. (2020) note that it is mostly accepted that concrete cylinders yield more reliable results than a cube, regardless of the testing circumstances which is attributed to the better compaction and uniformity (see Appendix 1).

However, such testing of concrete cylinders has varied challenges emanating from such factors as size, shape and friction. For instance, because of the cylindrical shape and size of the concrete, increased frictional forces resulted in concrete uniaxial compression and demand for more capping. The compressive strengths of the “large” concrete cylinders with the water-to-ratio of 4.0 and 90 days old have a mean (x̄) of 17.2778. In this regard, the sampling distribution of the sample means of compressive strengths is approximately normal. Since n=51.8335≥17.2778, the central limit theorem applies. Arguably, though the sample of the concrete strengths is skewed to the right, the sample average value is normally distributed because the sample size is large. The data set for the compressive strength established a standard deviation of 5.2173 (small value), which designates that the compressive strengths are clustered closely around the mean. Moreover, the lower the value of the coefficient of variation, the more precise the sample estimate. In this regard, the CV of 0.309, where 1> 0.309, stipulates a relatively high variation, thus more precision. Therefore, the “large” concrete cylinders were likely to be made from the same material.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the effect of the WCR ratio is different for various concrete shapes. For instance, as indicated in (see Figure 1), the compressive strength for cement paste cubes is higher than the compressive strength for “small” concrete cylinders. Notably, as the WCR ratio increases the compressive strength also decreases. When the WCR is low, the cement is probably containing unhydrated cement particles that remain within it making the crushing load to be more. In the “large” concrete cylinders, the experimental data is suggestive that they were made from the same material because of the small CV of 0.309, which is less than 1.

References

Talaat, A., Emad, A., Tarek, A., Masbouba, M., Essam, A., & Kohail, M. (2020). Factors affecting the results of concrete compression testing: A review.Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 1(1), 1-17. Web.

Qasim, O. A. (2018). A review paper on specimens’ size and shape effects on the concrete properties. International Journal of Recent Advances in Science and Technology, 5(3), 13-25. Web.

Appendix 1

Failure Acquired For Cubes and “Small” Concrete Cylinders under Compressive Load