Health Belief Model (HBM) is broadly applied in health promotion because it effectively influences people’s behavior by revealing their actions’ value. It has been developed in the 1950s by Hockbaum, Kegeles, Leventhal, and Rosenstock to explain the health services’ operation based on the goal-oriented decision-making model (McKenzie et al., 2013). HBM is crucial for public health because an individual’s actions towards healthy or preventative practices depend on modifying factors such as demographic and sociopsychological variables, mass media, and society’s awareness (McKenzie et al., 2013).

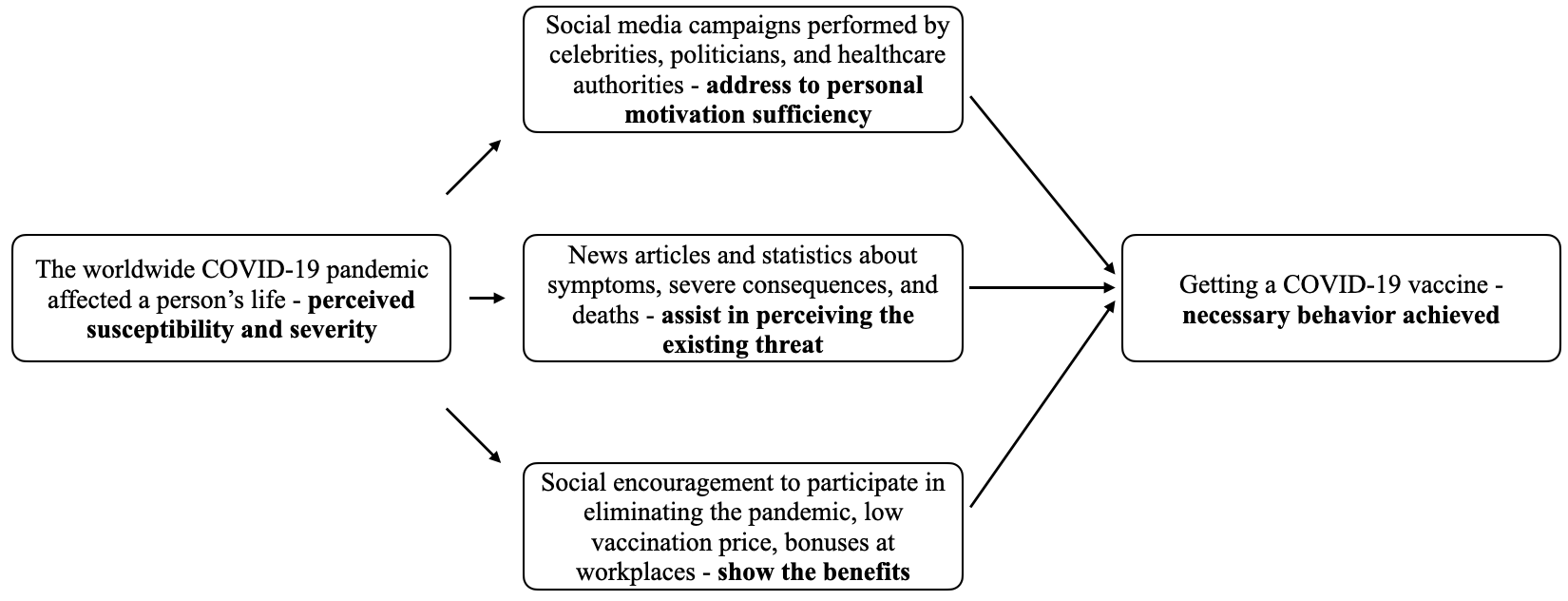

The concept is based on a person’s sufficient motivation to affect an issue, the existence of a threat, and the realization that the benefits are worth the cost (McKenzie et al., 2013). HBM is beneficial for detailed explaining individual behavior in detail based on psychological properties and structures, however, it overlooks macro-structures that constrain personal thoughts and motivations (Kim & Kim, 2020). In theory, the necessary behavior will be achieved when those three facts are addressed simultaneously.

The brightest example of influencing decision-making in public health is the recent COVID-19 vaccination promotion. Mercadante and Law (2020) state that “testing HBM with the willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine displayed that perceived benefits were significantly related to a “definite intention.” Besides, the demand in taking preventative action is broadly promoted in social media. Numerous campaigns describe the individual threats of avoiding immunization, and public health representatives encourage people worldwide to participate in eliminating the pandemic (Mercadante & Law, 2020). Kim and Kim (2020) claim that “when people are confident that a protective behavior is effective, and perceive low costs to adopting the precautionary behavior, they are more willing to adopt the recommended behavior.” The conceptual model below is based on the U.S. citizens’ behavioral patterns towards receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.

Perceived susceptibility and severity of an issue in HBM is defined as a factor that forces a person to seek preventative or helpful actions to take. In relation to getting the COVID-19 vaccine, all the citizens are aware of the pandemic, and its consequences affected everyone’s life. However, the biases about immunizations and the virus’s novelty decrease the willingness to prevent or eliminate the health issue (Kim & Kim, 2020). Consequently, the primary construct is the motivation sufficiency which must be increased by showing a person the social authorities’ example and displaying becoming vaccinated as proper civic behavior.

Identifying the possible threat is one of the concepts applied in HBM to move a person towards performing specific actions. Indeed, describing danger can be enforced by revealing the statistics about COVID-19 death cases and publishing information about the disease’s challenging course and consequences in the news. In addition to the motivation and understanding the danger of improper behavior, a person needs to realize that the benefits are worth the cost to take action. Thus, the vaccination’s promotion must address the low cost of the shot, social and workplace encouragement to cease the infection spread (Scherr et al., 2017). c

References

Kim, S., & Kim, S. (2020). Analysis of the impact of health beliefs and resource factors on preventive behaviors against the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8666. Web.

McKenzie, J. F., Neiger, B. F., & Thackeray, R. (2013). Planning, implementing, and evaluating health promotion programs: A primer (6th ed.). Pearson.

Mercadante, A. R., & Law, A. V. (2020). Will they, or won’t they? Examining patients’ vaccine intention for flu and COVID-19 using the Health Belief Model. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. Web.

Scherr, C. L., Jensen, J. D., & Christy, K. (2017). Dispositional pandemic worry and the health belief model: promoting vaccination during pandemic events. Journal of Public Health, 39(4), 242–250. Web.