Introduction

Hippocampus is a part of the limbic system. The limbic system comprises the subcortical structures and the cerebral cortex. The Cortical region includes the hippocampus, insular cortex, orbital frontal cortex, subcallosal gyrus, cingulated gyrus, and parahippocampal gyrus. The subcortical portion of the limbic system includes the olfactory bulb, hypothalamus, amygdala, septal nuclei, and portions of thalamic nuclei. The limbic system is normally looked at as the thinking portion of the brain and outputs to the nervous system.

The limbic system has its input and processing side as well as the output side that transmits the final decision to the nerves. The limbic cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus are considered the processing parts of the limbic system while the output part comprises the septal nuclei and the hypothalamus. Mostly the jobs done by the limbic system include species preservation and self-preservation reactions. They regulate both the endocrine and autonomic functions whenever there is an emotional stimulus.

Structure of Hippocampus

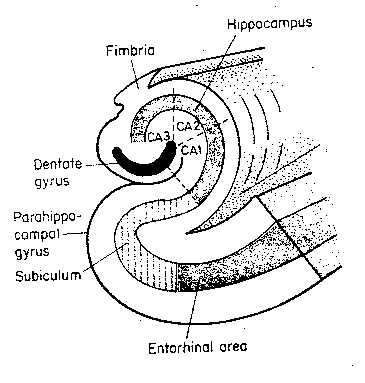

The structure of the Hippocampus can be looked at as a structure of three distinctive regions. Each one of these regions is formed by three different kinds of cells addressing three separate functions. (Figure 1). The dentate gyrus comprises granule cells while the CA1 and CA3 are comprised of pyramid cells. CA1 to CA4 form a part of the Cornu Ammonis (CA). Input to these neurons in CA1 comes mostly from the CA3 neurons which get their input from other CA3 neurons or from the dentate gyrus. The dentate gyrus in turn gets its input from the entorhinal cortex. In addition to this, the hippocampus gets its afferents from the septum and hypothalamus via the fornix.

This structure primarily helps the brain and the hippocampus in communicating with one another and in processing decisions. Communication happens in two phases. One, external when it is taken care of by the first messenger when the input comes from an external cell; two, when the input is internal and the message is transmitted from one to the other within a cell. Communication is achieved by using the synapse (Ben Best 1997). Every neuron in the human brain on average can handle 1000 different synapses.

Hippocampus connects through three synaptic circuits normally referred to as the Trisynaptic circuit. These pathways are underlying the entire communication system inside the hippocampus. Layer I and II of the dentate gyrus and the entorhinal cortex provide the perforant path which is a part of the Trisynaptic circuit. It was originally proposed that these specific portions of the hippocampus were found to be the one that promotes this communication which is essential for the memory and learning functions. Now, the stress is on the complete integrated three-dimensional functioning of the hippocampus (O’Reilly & Rudy June 2000).

The output from the hippocampus passes through two routes primarily. One, it passes through fornix. There are other fibers through which the hippocampus sends messages to the frontal lobe and then on to the entorhinal cortex. These would form the major after-process messaging of the hippocampus. Major functions of the hippocampus would, therefore, include several types of memory. In the case of implicit memory, it also helps in ‘learning’ where predefined decisions are stored for specific stimulants.

Learning and Memory

Many experiments have been carried out to ascertain the exact function of the hippocampus. However, some of the recorded effects of operations carried out on the human brain and its response to it have subsequently led to analysis of the effect and cause of specific problems. In one of the cases normally referred to as the case of “HM”, a patient with psychotic seizures was operated and his hippocampus was partially damaged. This led to a case of anterograde amnesia which was attributed primarily to the damage caused in the hippocampus. This and several other incidents revealed the close connection hippocampus had with memory. It was found that the hippocampus supports two main types of memory functions. One, the explicit memory, and the other the implicit memory; while the explicit memory is facts and numbers, the implicit memory is a derived memory based on incidents and experience (Swenson 2006).

The implicit memory helps the mind to come to a conclusion based on prior experience. Hippocampus supports both types of memories. Implicit memory is the one that is also called learning or thinking. In some cases, the established memories are moved to the frontal lobe and other associated areas in the cerebral cortex. A stroke resulting in the damage to the CA1 portion of the hippocampus also resulted in amnesia (Zola Morgan et al 1986; Horel 1994).

The initial thought of hippocampus being the central to learning and memory was found to have opposing pieces of evidence. There were also cases where damages done to the hippocampus during an operation did not create any large-scale amnesia as in the case of HM. Research on animals also indicates the role of the hippocampus to be of lesser magnitude than what was originally thought. However, it is now seen more as a part of the larger system of memory and learning control and there is certainly a role for the hippocampus but to what extent it could affect the learning and memory is not clearly established.

Many theories have been proposed by researchers on the subject of hippocampal function. Based on the memory type, David Olton (1977) proposed the Working or the reference memory system and the Declarative memory system. Many researches on animal performance using the hippocampus were performed and this resulted in many theories. This includes the following:

- Cognitive Map theory proposed by O’Keefe and Nadal (1978) and later researched upon by various authors also brings into focus the performance of the Hippocampus for the cognitive abilities of a person.

- Configural Association Theory proposed and developed by Ruth and Sutherland, further strengthened the concept of association with objects and events happening through the hippocampus.

- Path integration was proposed by Gothard et al (1996) and later extended by other researchers primarily bringing out a common and uniform path in communication that is in existence for realizing the actions of the hippocampus.

Work also centers around a more comprehensive theory that encompasses all that has been studied so far in connection with the hippocampus. This includes human lesion literature, experimental lesion literature, and hippocampal electrophysiology.

Conclusion

Hippocampus is in the path of processing and utilizing the learning process. It is also in the memory storage and retrieval process. This makes the hippocampus an important constituent of the circuit that is identified. However, the exact role or function of the hippocampus is still unclear. It can be taken as a supportive and important transition role. In the case of short-term memories, the hippocampus seems to be performing more elaborate roles whereas, in long-term memories, the information is passed over to other areas of the brain for processing. Hippocampus, therefore, is an important constituent of the memory and learning process.

Reference

Ben Best (1997) Learning Memory and Plasticity. Web.

Gothard KM. Skaggs WE. McNaughton BL. (1996). Dynamics of mismatch correction in the hippocampal ensemble code for space: interaction between path integration and environmental cues. Journal of Neuroscience. 16(24), 8027-40.

Horel J. (1994) Some comments on the special cognitive function claimed for the hippocampus. Cortex 30, 269-280.

O’Keefe, J. & Nadel, L. (1978). The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map, Oxford: Oxford U.P.

Olton, D.S. (1977). Spatial memory. In Atkinson & Atkinson (Eds.) mind and Behavior, Scientific American Special Issue , New York, Freeman Press, pp 171-181.

O’Reilly RC & Rudy JW (2000) Conjunctive Representations in Learning and Memory: Principles of Cortical and Hippocampal Function. Psychological Review, Vol 108, pp 311-345.

Swenson RS (2006) Review of Clinical and Functional Neuro Science. Dartmouth Medical School. Web.

Zola-Morgan, S., Squire, L.R. and Amaral, D.G. (1986). Human amnesia in the medial temporal region: enduring memory impairment following a bilateral lesion limited to field CA1 of the hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience, 6, 2950-2967.