Introduction

Shanghai and Hong Kong maybe some of the fastest-growing cities in the world. Both of them may be part of larger China, one of the most important and significant economies in Asia. However, it is a fact beyond doubt that these two cities are rivals as far as the international economy is concerned. Both of these cities compete for the position of Chinese international financial hub. This competition and rivalry have attracted the attention of international investors. This is given the fact that the investors would like to invest their money in a location that will attract fewer costs and larger profits. This is likely to be the city that will emerge as the international financial hub for China (Chen & Orum 2).

Shanghai is undoubtedly the most populous city in the larger China. It can be conceptualized as a Chinese global city. Shanghai is a significant city in China considering the influence that it has on the country’s commerce, finance, and other attributes of the Chinese society, including culture and entertainment (Frommer 2).

Shanghai may not be one of the oldest cities in China. However, it is not exactly a recent city either. Historians are of the view that the first signs of human settlement in this area can be traced back to the year 5000 B.C (Frommer 7). It started as a small fishing village along the shores of Wusong Jiang creek. However, shanghai was recognized between the 5th and 7th centuries, when it was included in the map of the country (Eisfelder 23).

Tang dynasty was one of the first regimes in China to recognize the potential of this fishing village. In the year 751, this region was made part and parcel of the larger Huating county. The major reason why this regime recognized the existence of this region is given the fact that it was located near Hangzhou. The latter was the capital city of the southern song dynasty, a dynasty that spanned from 1127 to 1279. In the year 1292, shanghai ceased to be a mere commercial center or a Zhen. It acquired a new status as a major political center when it became a county center, or a xian (Danielson 579).

According to the latest census figures in this city, the population now stands at 19,213,200. This makes this city to be the third-largest municipalities in the people’s republic of China. It comes third only after Chongqing and Beijing. Successive census figures have pointed to the fact that the population in this city has been on a growing trend in the recent past. For example, it is estimated that since the year 1990, the population in this city has risen by about 25 percent (Danielson 579).

Experts around the world are in agreement that shanghai is one of the fastest-growing cities in the world. These experts are of the view that the rapid rise of this city as one of the world’s major globalizing cities is something that has not been recorded in the past. This point is supported by the fact that the economy of this city’s economy has a significant effect on the global economy in extension. For example, the stock exchange in this city experienced one of the major declines to be recorded in an Asian economy on 27th February 2007 (Deke & Tess 32).

This development affected other major economies in the world. One of the notable parties to be affected by this development was the Chicago Olympics committee. The latter had made a very serious bid to be the host of the 2016 summer Olympics. As part of their efforts in this bid, the committee decided to set up an international operations office in shanghai in February 2007 (Deke & Tess 30).

Many cities around the world, noting the meteoric rise of Shanghai as an international economic hub, have launched development plans that are aimed at turning to copy the development path that was followed by shanghai. In short, the events that have taken place in this city over the years have conferred upon it the status of a role model for many other cities around the world. A case in point is the city of Bombay, one of India’s significant economic hubs. Bombay has come up with a strategic plan that is aimed at making it achieve the status of current shanghai within the next few years (Chen & Orum 7).

The discourse above points to the fact that shanghai has emerged as one of the most significant cities in China and in the world in extension. This is notable given the fact that the city has evolved from a small fishing village to such an important aspect of the global economy. As such, the claim of this city to be China’s international financial hub can not be taken lightly.

On the other side of the ring in this contest for China’s financial hub in Hong Kong. This city, just like shanghai, has a relatively long history as part of the larger China. Historians are of the view that early life in this region existed as early as 6,000 years ago. This is when settlements started to appear along the shores of Hong Kong.

This city has developed from a coastal island on the southern coast of China (Fowler & Fowler 263). Despite the fact that this city has a long history as evidenced by archaeological findings, recorded or written history in this region started when it came into contact with imperial China and the British colony. Just like shanghai, it started as a fishing village that complemented its commercial activities by trading in salt and other such products (Fowler & Fowler 267).

Given the strategic location of the city, the Chinese government attached a lot of significance to Hong Kong as a strategic military base. This recognition has been instrumental in making this city one of the world’s financial centres. According to recent statistics, this city boasts of the world’s 6th highest gross domestic product (herein referred to as GDP). It also accounts for about 33 percent of foreign trade for the larger China (Westra 19).

As of the year 2008, the population of this city stood at 7,018,636. This signifies a growth rate of about 0.5 percent. The population size and the growth rate are low as compared to those of Shanghai as analysed earlier in the paper. But the picture is altered significantly when one puts into consideration the size of the city. Its total size is 422 square miles, and the population density stands at 6,735 per square mile (Rikkie 16).

The competition that this city has with Shanghai for the status of China’s international financial hub is also significant. This is given the fact that the economy of this city can compete with that of Shanghai, despite the fact that the two economies might be slightly different (Rikkie 23).

This research paper is going to look at the competition and rivalry that exists between these two cities as far as China’s international financial hub is concerned. The researcher will try to find out which of the cities deserves the title of China’s international financial centre. The researcher is going to support their assertion by analysis of literature that exists in this field (Dudley & Poston 14).

This paper is going to look at the historical backgrounds of both Hong Kong and Shanghai. The researcher will in particular look at the financial structure of the two cities. This is by paying special attention to several attributes of the two cities’ financial markets. This will include the exchange volume and the foreign investment into these two markets. The paper will also focus on the Chinese government’s financial policy regarding the two cities, including but not limited to the RMB Yuan (Schifferes 5).

The above are just some of the areas that will be addressed by this study. This study will assume a review of literature design. Given the fact that it will be hard for the researcher to conduct an experiment between the two cities and the investors within the two markets, this study will not be able to generate primary data. As such, the literature in this field, including the findings of studies carries out within this field, will be used as the major source of data for this study. The researcher will get information from sources such as online publications of the developments and performance of the two cities’ stock market (Martig 26).

Historical Backgrounds of the Two Cities

Shanghai: Historical Background

When the city of Shanghai is mentioned, many people think of the tepid and sluggish waters that flow in the river Whangpoo. This is the river that borders this city to the right. The city is located approximately 15 kilometres from the place where the Whangpoo River joins the larger river Yangtze. This is the river that has given Shanghai the prominence of being one of the most important port cities in the world. This is given the fact that river Yangtze joins the China Sea a few kilometres down the stream. The sea is located on the western side of the Pacific Ocean (Martig 26).

Initially, Shanghai had an oval shape, a shape that made it one of the most notable towns in China. It was initially a small city, about one and a half kilometres across its widest area. Just like the Chinese great wall, Shanghai built a wall around the city in the year 1553 (Martig 26). The wall was aimed at keeping Japanese pirates that were terrorising the merchants in the city at bay. The wall was a permanent feature of the city for a period of about 359 years. This was before it was pulled down in the year 1912 (Martig 29).

The significance of this city as a major trading centre was notable during the 1840’s. This was the period that British engaged China in the infamous opium wars. This resulted from the ban that China placed on its citizens against growing of this crop, since it was considered as a crop that did not add value to the economy of the nation. The Britons, being the largest consumers of this plant from China, engaged this country in this war arguing that China was sabotaging the British economy (Poshek & Deser 349).

During this war, the residents of Shanghai city were able to raise about three million silver dollars, the amount of money that was necessary to pay off the Britons for them to spare the city. Considering that this city had about 250,000 residents, the ability to raise such a huge amount of money was no small fete to these residents. It points to the fact that the residents might have been wealthy to be able to raise such a huge amount of money (Poshek & Deser 349).

One of the milestones achieved by this city in its progress to a notable port city in the world was in the year 1842 (Poshek & Deser 349). This is the year that this city was designated as a treaty port. This meant that foreigners could engage in trade in this port while enjoying extraterritorial rights. However, it is important to note that the designation of this city as such could not have been a voluntary act on the part of the Chinese government.

This is considering the fact that China was forced to sign the treaty by the British, who used their military strength to get their way with the Chinese authorities, especially after the first opium was between the two nations. However, this forcing of the treaty upon the Chinese does not change the fact that Shanghai was a very important trading point for the world, led by the British. In fact, the fact that the British went as far as to force this treaty upon the Chinese acts as a pointer to the significance that was attached to this city (Tsang 19).

As earlier indicated, the proximity of this city to the mighty Yangtze River has increased its importance in the world of port operations. This proximity made this city develop into a major trading and manufacturing port that was used by many economies around the world. This is especially so given the fact that the size of the Yangtze River made it possible for large ocean going vessels to navigate it with ease. The vessels could conveniently access Shanghai, one of the most densely populated river regions in the world today (Richburg 7).

The population of this city rose to about 4 million by the year 1930. This rise in population was a clear indication of the fact that people were recognising this as one of the major trading centres in China. The status of this city as an important international city at this time was signified by the number of foreign embassies and consular that operated in the city from the early 1930s. The operations of these foreign embassies were an indication to the fact that foreign countries had interests in this city that had to be protected (Devonshire-Ellis 9).

The growth of the city of Shanghai can also be attributed to major crises that had befallen the larger China and the world at large. The city actually benefited from these crises. A case in point is the repeated attacks that were orchestrated by Japan against China especially in the years 1932 and 1937 (Jason 71). These attacks uprooted a large number of people from the larger China. Given the secluded nature of Shanghai- given that it was not part of the mainland China that was under attacks from the Japanese, many people seek refuge in Shanghai. Another classic example is the influx of Jewish refugees escaping persecution from Hitler in Germany in the late 1930s.

These refugees usually found that Shanghai was their only hope. This is given the fact that their access to other nations around the world was especially restricted. This was especially so in those countries that diplomatic or trade ties with Hitler’s Germany. The trooping of foreigners in the city was instrumental in raising the population of the city. The economy of the city was boosted by this influx given that many of these people came and settled as merchants, taking advantage of the strategic location of the city in the international trade route (Jason 72).

Shanghai has also benefited from other major crisis around the globe. This is for example the great depression of the late 1920s (Arthur 90). This led to many people seeking refuge in Shanghai, coming here either to escape the vagaries of the depression or to start their lives afresh after been devastated by the depression. The city also offered refuge to many people escaping wars and political strife from several parts of the world. The attractiveness of this city to these foreigners was based on the fact that the city had enclaves that were under foreign administration after the city had entered into agreements with several foreign governments.

These foreign administrative areas offered residence to the citizens of that particular nation and others who came seeking refuge from the hostile environment in their home countries. These foreigners increased the population of the city, and their engagement in trade further improved the economy of the city. They also brought with them foreign ties that had been instrumental in rendering this city an international face as far as international trade is concerned (Arthur 90).

The rule of Mao Zedong and his allies in the communist party in the 1970s threatened the status of Shanghai and other Chinese cities as international business hubs. This is given the fact that Mao and his ilk advocated for communism and condemned capitalism. This made Shanghai and China at large to be very unattractive to the international investors, who were dominantly capitalists (Arthur 90).

However, with the death of Mao Zedong and the loss of influence that his allies had in China in 1976, a wind of change started to blow from the Yangtze River across the city of Shanghai (Yash 95). This is especially so given the fact that the Nixon administration in Washington had earlier initiated talks with the Chinese administration to re-establish economic ties that had been severed by Mao and his allies. This led to the signing of what came to be known as the Shanghai communiqué in 1972. This was one of the agreements that were instrumental in re-establishing the trade ties between the two nations. The fact that this agreement was signed in Shanghai is a pointer to the fact that the international community still regarded this city as an important trade destination (Yash 96).

The Hongqiao Development Zone was set up in 1982 by the Shanghai authorities. The aim of this zone was to attract foreign investors back to the city, the investors that had earlier fled during the Mao’s rule. In the year 1990, this city was chosen as the one to lead in the economic reforms that had been proposed for the country by the then Chinese leader, Deng Xiaoping, a former Shanghai mayor (Russell & O’Brien 309). The city was also slated to be a financial hub, with the identification of the Pudong New Area as the city’s financial centre.

These developments have led the city to be regarded as the busiest and largest port city in the world today. This as far as the volume of cargo that is handled in this port on an annual basis is concerned. No other port in the world, not even the port of New York, handles such a large volume of cargo in any given year (Russell & O’Brien 306).

The dominance of the Shanghai city as China’s economic hub is not in doubt. However, questions still linger whether this status confers upon this city the additional and automatic status of being China’s international financial hub as opposed to Hong Kong. This question can only be comprehensively addressed by analysing the financial structure of the two cities’ financial market structures. This will be done after a historical review of the city of Hong Kong is carried out.

Hong Kong: Historical Background

As earlier indicated in this paper, life forms in this area have been assumed by archaeologists to have emerged as early as 30,000 years ago. The settlements were especially concentrated around the Sai Kung and Wong Tei Tung areas. This suggests that these were one of the most ancient human settlements in latter day’s Hong Kong (Russell & O’Brien 306).

Hong Kong became part of the larger Chinese territory during the Qin dynasty. This dynasty was in existence between the years 221 and 206 BC (Russell & O’Brien 306). However, Nanyue was the ruler that was able to firmly make Hong Kong part of the Chinese dynasty. This was between the years 203 and 111 BC (Russell & O’Brien 306).

The population of the region is said to have started to increase during the reign of the Han dynasty. This was between the years 206 and 220 BC (Arthur 90). This is an indication that during this time, the Chinese authorities recognised the importance of this region and started paying more attention to it. As an economic and trading hub in the Chinese dynasty, Hong Kong traces its history 2,000 years ago (Arthur 90).. Archaeologists are of the view that the region was a thriving trading centre around this time, specialising in the manufacture and selling of salt. However, evidence to support this is largely tentative and inconclusive (Arthur 90).

Between the years 1800 and 1930, Hong Kong was a British colonial territory. This was brought about by the heavy reliance that British had on this region during this period. British were especially dependent on importation of tea from China at the start of the 1800s (Arthur 90).

However, there was imbalance of trade between China and the British, and the British Empire benefited from this imbalance. This is given the fact that the items that China needed from the British Empire, items such as silver for her industries, could not be readily be supplied by the empire (Jason 72). This is given that the items and commodities were themselves rare in Britain. The imbalance in this trade led to illegal activities. For example, unscrupulous business men took advantage of this to start bringing opium illegally to China (Jason 72).

Realising the fact that these illegal dealings in opium and other items posed a threat to the stability of the Hong Kong society and economy, the administration took measures to try and curb the practice. A notable case of these efforts is when Commissioner Lin Zexu sought audience with the British queen Victoria. The commissioner stated the position of Hong Kong and China regarding their opposition to this illegal trade. Given the significance that the queen and her allies attached to this trade, a conflict eventually started. This culminated in the infamous opium wars of the early 1840s (Jason 72).

Given the military strength of the British army, a strength that was unmatched by the undeveloped military technology of China, the latter stood no chance in the ensuing conflict. China was decisively defeated in all the engagements and confrontations in these wars. In the year 1842, the strength of the British army was signified by the forced cession of Hong Kong to the British Empire. This was after the British and the Chinese authorities signed a set of new treaties in this year, treaties that China had to acquiesce to in order to avoid further losses from the war. This marked the beginning of the era of Hong Kong as a British colony (Jason 72).

The settlement and rule of the British in this territory did not go unchallenged. In the year 1899, one of several attempts by the natives to rebel against the occupation and rule of the foreigners was made. This was when the natives staged a protest in the Kam Tin area (Jason 72). Despite the fact that this uprising was not successful, its significance did not go unnoticed to the colonials.

During this period, Hong Kong was separated from mainland China not only geographically, but also philosophically. A western form of education was started by the colonialists. This development was especially significant in the period that mainland China was under a political upheaval that was brought about by the incompetence rule of the Qin dynasty.

The strategic location of this city has been both a blessing and a curse to its development. For example, its isolation from mainland China and easy access from the sea had made vulnerable to foreign attacks over the years. When the First World War broke out in the year 1914, many people fled the island fearing for their safety. Analysts put the number of those that fled the city to about 60,000. This was a significant number given the isolation of the city and the size of the population by then. The population stood at 530,000 in the year 1916, a few years after the beginning of the First World War. This increased to about 725,000 in the mid 1920’s, a clear evidence of the importance that people placed on this city despite her vulnerable geographic location (Jason 72).

After the British left the island in the 1930’s, another occupier in the name of Japan took their place. The strategic attacks and eventual occupation by Japan was brought about by several factors. This included the economic and political turmoil that mainland China was going through during the 1920s and 1930s. This, compounded by the geographical isolation of this city from mainland China, hampered the ability of the Chinese to protect and claim this region after the departure of the British.

The rivalry between the allied forces on one hand and Japan on the other caught Hong Kong Island in the middle. The Japanese were able to attack and drive away the allied forces from the island, paving the way for the Chinese occupation between the 1941 and 1945 (Poshek & Deser 348).

Economically, the period of Japanese occupation marked one of Hong Kong’s low moments. There were high levels of inflation, and the authorities introduced strict food rationing policies. The trade was negatively affected, given the fact that the international community and the locals found the environment in Hong Kong during this time to be so hostile for any meaningful business ventures.

Hong Kong dollar, the currency that was used during the British occupation, was phased out by the Japanese. They replaced it with the Japanese military yen. This was the currency that was issued by the occupiers’ imperial army. This was one of the factors that led to high levels of inflation, given the fact that this currency had no reserve (Poshek & Deser 349).

The rule of the Japanese came to an end by the close of the world war in the year 1945. By this time, it was estimated that the population of this city had dropped to about 600,000 residents. This is as compared to the number of residents in the city in the early years before the occupation by the Japanese, for example the 725,000 estimates of the year 1925 (Poshek & Deser 341). Analysts put the population of the city immediately before the occupation of the Japanese at about 1.6 million, further signifying the negative impact of the Japanese occupation.

However, just like in the case of Shanghai, Hong Kong was to benefit from the political and economic turmoil that were to embroil mainland China in during the reign of Mao Zedong and the communist party. For example, following the economic censorship that came with the introduction of the Great Leap Forward of the Mao’s regime, many people fled to Hong Kong (Poshek & Deser 349).

From the start of the 1950s to the early 1990’s when the British came back to control the island, an economic boom was evidenced. For example, those refugees from mainland China brought with them capital and skills that were important in the re-building and growth of the economy. This led to the establishment of manufacturing industries in this city at this time.

This growth in the city’s economy was momentarily disrupted when there were talks between the British and the administration in the mainland China touching on the handing over of this city to the people’s republic of China. This was in the early 1980s. During this time, this city had earned itself the recognition of being one of the wealthiest cities in Asia. It was proposed that the city will be handed over to the Chinese administration in 1997 (Martig 26).

Naturally, this development triggered a panic button on the part of the investors in the city. This is given the fact that the investors were basically capitalists. The handing over of their territory to communist China was unsettling to them. This led to huge capital and human resource flight. The fled was to the United States of America, Canada and other states that were considered to be safe from the influence of the communist movement.

Hong Kong ushered in the 21st century as a Chinese territory. Many people who were hitherto against the handing over found themselves having to adjust to the new conditions. By the year 2003, the population of this city had reached approximately 6,800,000 (Martig 26). The economy of the city has continued to grow, making the city to emerge as one of the most important Chinese economic centres. The city has also made steps to become the regions international financial hub. For example, in the year 2003, Two International Finance building, one of the tallest in this city, was commissioned. This was succeeded by the latest International Commerce Centre, a building that was completed in the year 2010. These are just some of the notable efforts by this city to become the region’s international financial centre (Martig 26).

The discourse above also points to the fact that, just like in the case of Shanghai city, the claim that Hong Kong city has to the status of China’s international financial hub can not be ignored. This leads to the analysis of which between these two cities has a justifiable claim to this title.

Hong Kong and Shanghai’s Financial Structure

Preamble

In the previous section, the researcher looked at the historical backgrounds of the Shanghai and Hong Kong cities. The historical backgrounds traced back the roots of the cities from the early civilisations of the cities, the colonial administrations of the cities to the current status of the cities under the people’s republic of China. The aim was to contextualise the two cities within the discourse of this paper. The discourse set the stage for the analysis of the two cities claim to the status of being the Chinese international financial centre.

In this section, the author is going to provide the reader with the financial structure of the two cities. The history of the two cities’ as far as their financial structure is concerned will be provided. The aim is to provide the reader with a context of the two cities’ claim to this status.

Shanghai’s Financial Structure

The financial structure of this city can be conceptualised from the perspective of the city’s stock exchange market. The people’s republic of China has three autonomous stock exchanges operating within it. These are the Shanghai stock market, the Hong Kong and Shenzhen stock markets. The latter two are open to the foreign investor. However, the one in Shanghai is yet to embrace the investment of the international business man (Rikkie 20).

Taking market capitalisation as the yard stick, the Shanghai stock market is the sixth largest globally. The capitalisation of this market stands at 2.4 trillion US dollars. This is as at August 2010. The Chinese mainland government has a tight and close control over this market. This is one of the reasons why it is not yet open to the international investor (Russell & O’Brien 308).

The Shanghai stock market operates on a non-profit basis. It is under the direct control of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (herein referred to as CSRC). The market was reopened in the year 1990, after having been closed down briefly.

However, it is important to note that the history of this stock market is fairly long. It can be traced back to the treaty of Nanking, a treaty that was signed in the year 1842 (Yash 97). As earlier indicated in this paper, this was the treaty that led to the end of the first opium war. This treaty defined the conduction of trade between China and the rest of the world.

The securities market in this city began in the late 1860s. On June 1866, trading can be referred to as the first form of shares in this city appeared in form of securities. This was made possible by the city’s international settlement that provided the suitable conditions for such form of trade. This was in form of several banks that were in operation, a legal structure that governed the joint stock entities and an interest on the part of the investors and the trading houses.

The forms of securities that were traded in this city varied depending on the prevailing economic activities. For example, in the year 1891, the major economic activity in Shanghai was mining. This led to a rise in the number of mining shares that were traded between the business men in this city, majority of who were foreigners. The same year, the stock market in the city was founded under the name of Shanghai share brokers’ association. This was China’s organised stock exchange market. This association was however registered as another form of entity in the year 1904. it was registered in Hong Kong as the Shanghai stock exchange, and thus was formed the current Shanghai stock market (Schifferes 2).

The operations of this market were marked by differing rates of success over the years. This is especially so as the city emerged as an international manufacturing and trading centre. The manufacturing companies and the merchants, majority of who were foreigners drawn from various parts of the world, formed the backbone of the securities market, providing market for the securities. The market saw the traders buy and sell stocks, debentures and governments bonds. This form of operation was not unlike the operation and conduction of any modern stock market (Arthur 95).

However, the onset of the First World War and the eventual occupation of Shanghai by the Japanese was a dark moment for the Shanghai stock market. When the Japanese troops captured and started ruling this city’s international settlement in the year 1941. The stock market was halted immediately after the occupation. The closure was in operation until the year 1946. In this year, the market was opened, but it was closed down three years later (Dudley & Poston 28).

The year 1949 saw the onset of the communist revolution in China. As expected, the communism dogma did not favour the stock exchange market. This is given the fact that the investors in the stock market are basically capitalists, aiming to make profits from their investments. This is against the spirit of communism, which advocates for equal distribution of resources. As a result of this revolution, the Shanghai stock market was closed down again in the year 1949 (Richburg 7).

The Shanghai stock market remained closed throughout the reign of Chairman Mao Zedong and the communist party. The political and economic conditions during this time could not support a securities market. It was only after the Cultural Revolution came to an end and Deng Xiaoping took the reigns of power were efforts made to revive the stock market.

After the rise of Xiaoping to power, efforts were made to re-establish economic ties with the western and capitalist world. Economic reforms were introduced starting from the 1980s. The securities market in this country developed as the economy of the country grew with the rest of the world. This development was made possible by the opening up of this country’s economy to the socialist and capitalist economies of the world. This led to the reopening of the Shanghai stock market on 26th November 1990 (Rikkie 20).

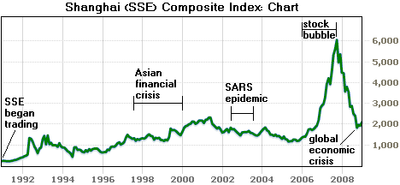

The performance of this market from the year 1992 to the year 2008 can be deciphered from the chart below:

Structure of the Shanghai Stock Exchange Market

Before looking at the performance of the stock market, it is important to first look at the structure of the Shanghai stock market. The structure of this market will provide a context within which the performance analysis will be carries out.

The securities that are listed in this market include three main categories. These are stocks, bonds and funds. There are various forms of bonds that are exchanged in this market. These are for example the treasury bonds, corporate bonds and the convertible corporate bonds among others. This market’s Treasury bond is considered to be the most active and most traded in the whole of China.

The structure of the stock market is further structured to two types of stocks that are offered in the market. These are the A shares and the B shares.

The differentiation between the A and B shares is in the currency that they are priced in. the former are priced in the local Renminbi Yuan currency. This is as opposed to the latter, which are priced in United States of America dollars. “A” shares are reserved to the domestic investors initially, and the international investors were not allowed to trade on them. However, since the year 2001, the B shares are open to both the local investors as well as the international or foreign ones (Rikkie 17).

Reforms that have been carried out in this market since late 2002 have allowed the trading in “A” shares by the foreign investors. This allowance to trade is however limited. It has been allowed to take place under the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (herein referred to as QFII). The program was officially launched in the year 2003. To date, about 98 foreign investors had been cleared to trade in these A shares. The quota that has been achieved under this program stands at 30 billion US dollars as to date. The administration has made plans to merge the two forms of shares so that they can trade without the distinction in the future (Tsang 19).

Just like in other stock markets in the world, the Shanghai stock market operates between Monday and Friday of every week. A typical morning begins with a centralised competitive bidding that runs from 9.15 to 9.25 in the morning. This is followed by a consecutive bidding that starts from 9.30 and runs to 11.30 in the morning. In the afternoon, the consecutive bidding goes on from 1.00 to 3.00 in the afternoon. The market does not operate over the weekend and on other holidays that are identified by the Shanghai stock exchange (Arthur 99).

Performance of the Shanghai Stock Market

By early 2008, there were 861 companies that were listed in this market. The total market capitalisation at the same period stood at RMB 23,340.9 billion. This translates to about 3,241.8 billion US dollars. This is considering the fact that 1 US dollar exchanged for about 6.82 RMB at the time (Rikkie 18).

The table below depicts the performance of the Shanghai stock market in the year 2007:

Table 1: Trading Summary for the Year 2007

Adapted from: Richburg 5

Like in other stock market in the world, the Shanghai stock exchange makes use of an index to track the performance. This market makes use of the Shanghai composite. It is used to reflect the performance of the market in a given period of time. Both the A shares and B shares are used in compiling the composite index. December 19 1990 is usually used as the base day when compiling the performance indicators for the market. The aggregate of a given day’s market capitalisation is referred to as the Base Period (Rikkie 18).

From the above analysis, it is noted that the financial market of this city is one to reckon with. This makes it one of the most important financial centres in the country. However, before looking at the financial structure of Hong Kong city, a decision can not be made to confer the status of the international financial centre for China to this city.

Hong Kong’s Financial Structure

Just like in the case of Shanghai city, the financial structure of Hong Kong’s city will be analysed using the structure of the Hong Kong stock market.

This is Asia’s second largest stock market as far as market capitalisation is concerned. It is only second to the Tokyo stock exchange in Japan. This means that it is larger than the earlier analysed Shanghai stock market. By the end of August 2010, there were 1,356 companies that were trading in this market. This is as compared to the slightly more than 800 companies that are listed in the Shanghai stock exchange. The market capitalisation at the same time stood at 2.3 trillion US dollars. The market is held by the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Company (Fowler & Fowler 268).

The history of the stock exchange is equally as long as that of the Shanghai stock exchange. It can be traced back to the late 1800s. The first kind of a securities market in this city was started in the year 1891. however, history has it that the informal trading in securities in this town started as early as the year 1861, just like in the case of Shanghai securities market. This is an indication of the fact that the histories of the Shanghai and the Hong Kong securities are intertwined and related. The two stock markets have coexisted at various points in their history. However, between the years 1947 and 1969, the Hong Kong stock market was the major player in the market (Fowler & Fowler 270).

The stock market, like in the Shanghai stock market, opens from Monday to Friday. The market opens at 9.30 in the morning, and the opening and bidding price for the securities is reported twenty minutes after that. The morning session continues between 10.00 in the morning and 12.30 in the afternoon. In the afternoon, the market operates between 2.30 and 4.00 pm, when it finally closes for the day (Fowler & Fowler 270).

This market has however been faced by cases of market manipulation accusations. However, an investigation to some of those accusations revealed that it was the operation mode of the market of that was to blame, but not the deliberate acts of any human actors. It was revealed that the method that was used by the market to calculate the opening prices for the stocks led to fluctuations in the prices, fluctuations that made the investors and other market players suspicious. This was especially the method that was introduced and was in operation from mid 2008 (Fowler & Fowler 270).

To deal with these fluctuations, there were proposals to cap the fluctuations at 2 percent during the trading sessions. However, this did not work as expected, and the closing session formula was totally abandoned in March 2009.

It has been argued that the market should cut back on the amount of time that is spent as a lunch break during a normal trading day. The lunch break goes for two hours, as compared to that of Shanghai stock market that is much shorter. In fact, it is said that this market has one of the longest lunch breaks when compared to other markets in the 20 major stock exchanges in the world, of which Hong Kong stock market is a member. A proposal was made in the year 2003 to shorten this lunch break. However, stiff opposition from the stock brokers operating in the market led to the abandoning of the idea (Westra 22).

This analysis also points to the fact that the Hong Kong stock market, or the city’s financial structure, is as significant as that of the Shanghai economy. So far, the question as to which city should be crowned as China’s international financial centre remains unanswered. This means that a direct comparison has to be carried out between the two cities.

China’s International Financial Centre: Is It Shanghai or is it Hong Kong?

The competition between these two cities has been fierce. Sometimes, the competition is explicit and covert, for example when public figures from either side make public declarations making their stand known. A case in point is Tu Guangshao, one of Shanghai’s deputy mayors. On 26th July 2010, this official was quoted as saying that it is paramount for the China government to officially declare the city as her international financial centre (Devonshire-Ellis 9). The vice mayor went as far as to state that the Chinese government should promote Shanghai city over that of Hong Kong in the international market, using it to capture the attention of the international investors to China (Devonshire-Ellis 11).

This debate has polarised both of the cities, putting them at opposing sides of the debate. It is not only the business community and residents of the cities that are sucked into the whirling pool that is this debate. The controversy extends to the residents and the business community in mainland China. This is given the fact that these residents, depending on their personal and business interests, advocate for either of the two cities to be declared as the international financial centre for their country. This means that the debate is far from being resolved, if at all it will be resolved (Westra 22).

There are those sober minds advocating for the adoption of the Shanghai city, minds sober enough to admit the fact that the city of Shanghai is not likely to catch up with that of Hong Kong till the year 2020 (Devonshire-Ellis 11). This is as far as the infrastructure and the size of the economy is concerned. However, the same elements claim that the Shanghai city has a larger potential than that of Hong Kong, and this alone should make it the automatic international financial centre for China. They cite the rate at which Shanghai’s economy has grown over the past few years. These are individuals such as the Shanghai communist party leader. This is Yu Zhengsheng (Devonshire-Ellis 9).

Tu authored one of the most influential reports that support the case for Shanghai in 2008. According to this report, it is Shanghai and not Hong Kong that has the ability to handle the rigors of an international financial centre in the long term. Some of the recommendations in this report included measures that should be adopted by the Chinese government to make this city an international financial destination by the year 2020. The report was so influential to the extent that it was officially adopted by the state council in the year 2009 (Devonshire-Ellis 9).

Currently, according to this report, China appears to have two financial centres. These are Hong Kong and Shanghai. According to the same report, the Chinese government has to make a decision and select one of the cities as the designated financial hub. This is given the fact that in the long run, it is not possible for the country to keep the two centres together. It will appear that one of the centres might be neglected and this might affect the Chinese competitive edge in the international financial market. As such, a conscious and deliberate decision has to be made by the Chinese authorities to adopt and promote one of these cities as the international financial market (Devonshire-Ellis 7).

The report is of the view that the best decision to make under the circumstances would be that which will recognise Shanghai as the designated centre. It is important to note at this juncture that while the final resolution of this report was in favour of Shanghai, not all the authors were in agreement. There were some dissenting voices that were concerned on the suitability of this city as the Chinese flag bearer in the international financial market (Devonshire-Ellis 4).

In his personal capacity, Tu is of the view that the decision to designate Shanghai the international financial centre for China can be justified from the perspective of the international community. His aggressive campaign is not unlike that of other officials from the Shanghai side of the divide. Regarding the views of the international community, Tu claims that the investors view Hong Kong and Shanghai differently. For example, the international investor does not see Hong Kong as the major financial centre fit for the international market. They regard as a regional giant that is fit only to serve the Asian regional market. This is especially so given the fact that the international investor views Hong Kong as being a part of the larger mainland China, and in extension, as having all the trappings and attributes of a controlled Chinese economy (Devonshire-Ellis 16).

In the eyes of the international investor, Shanghai is the ultimate Chinese international financial centre that is bound to meet their requirements. The Shanghai economy, together with the riding infrastructure, is an indication of how the international community looks at China.

At the risk of appearing to have been influenced by the contents of the Tu report, this author is of the view that Shanghai really deserves to be the international financial destination for China. The author is in agreement with most of the arguments that are fronted by the vocal Shanghai politicians and their sympathisers. However, the author feels that Shanghai needs some workings on several of its aspects to finally gain the full trust of the Chinese government and the international community of investors.

There is a fact that should be kept in mind by all those advocating for the adoption of Shanghai as the international financial centre for China. First, it should be noted that the city is not yet an international financial centre as of now. This is despite the fact that Tu and his ilk would like to make one believe otherwise. There are also some limitations and restrictions that are put on the Shanghai financial market that acts as a hurdle in the development of the city.

This is for example the policy that has been adopted by China regarding the RMB Yuan, the major currency in Shanghai (Devonshire-Ellis 9). The government has restricted this currency, and it cannot be internationally exchanged. This means that unless the government rescinds this decision and makes it tradable on the international arena, there is no way that Shanghai is going to attain the status of an international financial hub. This is especially so given the fact that the Hong Kong dollar is tradable on the foreign market (Devonshire-Ellis 7).

There is also the issue of the control that the mainland Chinese government has on the Shanghai stock market. For example, foreign investors can not access the stocks of mainland Chinese companies on the Shanghai bourse. The Chinese government also holds a substantially large share of the market capitalisation on the Shanghai bourse. This has led to claims of manipulation of stock and vested interested from the international community. Unless the government of mainland China changes this, the international community will continue regarding the status of Shanghai as an international financial hub sceptically (Devonshire-Ellis 2).

Conclusion

It is a fact beyond doubt that Hong Kong has a fairly larger economy as compared to that of Shanghai. However, an analysis of the situation will reveal that Shanghai is the best option as far as a Chinese international financial centre is concerned. In the long term, Shanghai has a larger potential to take this role as compared to Hong Kong. This is especially so given the fact that the international community regards Shanghai favourably.

However, the Chinese government must ensure that some sweeping changes are introduced into the Shanghai financial market. This includes easing of control over the securities’ market, especially when it comes to the currency regulations. Unless these changes are carried out, Shanghai, despite her huge potential, will not be able to attain and maintain the status of Chinese international financial centre.

Works Cited

Arthur, Starling. Plague, SARS, and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006. Print.

Chen, Xiangming, and Orum, Anthony M. “Shanghai as a New Globalising City: Historical, Theoretical, and Analytical Lessons for and From Shanghai.” Google, 2009. Web.

Danielson, Eric N. Shanghai and the Yangzi Delta. New York: Free Press, 2004. Print.

Deke, Erh, & Tess, Johnson. Shanghai Art Deco. Hong Kong: Old China Press, 2007. Print.

Devonshire-Ellis, Chris. “Chris Devonshire-Ellis: China’s Financial Centre, Shanghai or Hong Kong.” China-Briefing, 2010. Web.

Dudley, So, & Poston, Nan. The Chinese Triangle of Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong. New York: Greenwood Publishing, 2001. Print.

Eisfelder, Horst. Chinese Exile: My Years in Shanghai and Nanking. London: McGraw-Hill, 2008. Print.

Fowler, Jeaneane D., & Fowler, Merv. Chinese Religions: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press, 2008. Print.

Frommer, Fredrick. “History for Shanghai.” Nileguide, 2010. Web.

Jason, Wordie. Streets: Exploring Hong Kong Island. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2002. Print.

Martig, Naomi. “Hong Kong vs. Shanghai: The Race has Just Begun.” Google, 2010. Web.

Poshek, Deniel, & Deser, Bient. Political Change and the Crisis of Legitimacy in Hong Kong. Hawaii: University of Hawaii, 2002. Print.

Richburg, Keith B. “Shanghai Poised to take on Hong Kong as China’s Financial Hub.” WashingtonPost.com, 2010. Web.

Rikkie, Yeung. Moving Millions: The Commercial Success and Political Controversies of Hong Kong’s Railways. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008. Print.

Russell, Peter & O’Brien, David. Judicial Independence in the Age of Democracy: Critical Perspectives from Around the World. Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 2001. Print.

Schifferes, Steve. “Hong Kong v Shanghai: Global Rivals.” BBC, 2007. Web.

Tsang, Xengrim. Macau, The Imaginary City: Culture and Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Print.

Westra, Nick. Hong Kong as a Cantonese Speaking City. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, 2007. Print.

Yash, Pal G. Autonomy and Ethnicity: Negotiating Competing Claims in Multi-ethnic States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Print.