Introduction

This chapter contains a review of existing literature concerning hotel pricing strategies and customer booking behaviors. The analysis is centered on reviewing the main factors influencing pricing in the hospitality industry and their contribution towards understanding customer behaviors in hotel booking. However, before delving into the details of this analysis, it is (first) important to understand the critical forces influencing the hospitality industry.

E-Commerce

Many studies consider e-commerce to be a critical force defining how hotels interact with their customers (Chae, Koh & Prybutok 2014; Buil, Martínez & Chernatony 2013b). The growth of this form of technological advancement means that the hospitality industry has a new reality in the way it operates. More importantly, the growth of e-commerce means that stakeholders in the sector have to rethink how they do business with each other and with their customers. Studies that have investigated how companies operate on the online platform have shown that consumer-buying behavior is mostly influenced by functional, hedonic, innovation, and aesthetic needs (Chae, Koh & Prybutok 2014; Buil, Martínez & Chernatony 2013b).

Before the growth and spread of the internet in the hospitality industry, global distribution systems (GDS) played a key role in facilitating international commerce. According to Buil, Martínez, and Chernatony (2013b), the GDS played a functional role in the industry by coordinating the functions of brick-and-mortar businesses and travel suppliers. However, with the growth and development of e-commerce in the 1990s, hotels and travel agencies changed how they operate their businesses by embracing the virtual platform (Jang, Tang & Park 2013).

At the time, major global hotels embarked on an aggressive marketing campaign to popularise their brands online (such as through their websites) (Chen 2014). A more interesting trend that emerged at the time was the reclaiming of value chain controls by hotels from travel agencies, which were their main source of business. Afiouni, Karam, and El-Hajj (2013) refer to this trend as “disintermediation.” Today, hotels and airlines have fully embraced this trend because they reach out to their customers directly to improve their business-customer experience and enhance customer satisfaction standards.

Buil, Martínez, and Chernatony (2013a) say that online direct distribution is more important for hotels that have loyalty programs than those that do not have the same programs. This is because when customers visit their websites, they are rewarded for doing so (repeat business). At the same time, loyalty programs are important to these businesses because they allow them to maintain a database for improving their products and services further (Jang, Tang & Park 2013). Many hotels that develop individualized services commonly use this strategy (Afiouni, Karam & El-Hajj 2013). Moreover, most of them have used the same plan to forge relationships that are more intimate with their customers. Based on the success of such methods, several research studies have pointed out the need for hotels to use direct marketing platforms to build effective customer relationships, and bolster customer loyalty standards (Chae, Koh, & Prybutok 2014; Buil, Martínez & Chernatony 2013b).

Hua, Morosan, and DeFranco (2015) say that the growth and development of e-commerce have increased business opportunities in the hospitality industry. Online travel retailers have realized the potential that exists in this space and exploited it to account for about 50% of all online hotel bookings today (Chen 2014). Four main types of travel intermediaries have done so and they include virtual travel sites, meta-search engine sites, social media sites, and flash sales sites. Online travel agencies that have relied on e-commerce for growth include Orbitz.com, Expedia.com, and Hotel.com (Chen 2014). Other companies that have achieved the same level of success include Travelocity.com and Priceline.com. These online travel agencies operate using one of three business models: a commission-based model, a merchant framework, and the opaque selling model (Chen 2014).

Meta-search websites operate differently from online travel agents because they obtain information from a list of websites and package the same data to create a common database for customers to select a hotel, based on individual preferences. Google is one of the most commonly used meta-search websites for making hotel bookings, but others that provide the same service, and have a relatively significant following, include Kayak.com and Bookingbuddy.com (Hua, Morosan & DeFranco 2015). Generally, these websites streamline the search process for their customers. In other words, they not only allow users to view available accommodation facilities but also compare them with each other.

Social media websites are different from meta-search websites because they provide user-generated data. Many hotels ignored this platform for a long time because of its unregulated nature, but have recently reconsidered this decision. Consequently, many of them run social media accounts on various platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, to direct customer traffic to their websites and to address some of their customer issues online. TripAdvisor is one of the world’s most popular user-generated online platforms in the industry (Hua, Morosan & DeFranco 2015).

Lastly, flash sale platforms offer customers limited products for a subsidized price and for a limited time (Chiu & Chen 2014). Usually, these offers last for up to 48 hours, and they are often given to customers who have registered accounts on the platforms. Some of the most common websites that fit this description include Groupon-Getaways and Living Social-Escape. Many hotels collaborate with such companies for several reasons, including increasing off-season occupancy rates and enhancing the profile of their properties (usually to appeal to new market segments) (Chae, Koh & Prybutok 2014; Buil, Martínez & Chernatony 2013b).

The Impact of E-Commerce on Hotel Pricing

Customers are often on the lookout for deals that give them value for their money. This point of view suggests that the perception of hotels and their customers regarding product value and risks are the main forces influencing pricing strategies. Studies also show that consumers often have different risk reduction strategies that they employ while shopping online because of the uncertainty associated with making virtual reservations (Hua, Morosan, & DeFranco 2015).

For example, some customers are hesitant to make reservations because of the belief that better deals will show up if they wait. Based on this analysis, many hotels are starting to realize that they are working with a group of well-informed customers who are always out to exploit suppliers’ pricing strategies. Based on the realization that the number of tech-savvy customers is slowly rising, many hotels are under pressure from experts who suggest they should use a dynamic pricing strategy across all their distribution channels (Hua, Morosan & DeFranco 2015). However, Monga and Kaplash (2016) caution that the application of this dynamic pricing strategy requires a full realization (by hotels) that it involves the interplay between a customer’s perceived value of the hotel’s products and the perceived risks of the hoteliers.

Several researchers have identified the dynamic pricing strategy as having the potential to increase hotel revenue because it not only attracts price-sensitive customers but also uses analytical pricing models that include different types of information, including the history of customers and their characteristics, to ascertain the right price (Monga & Kaplash 2016). This pricing model also focuses on real-time reservations, which are critical in the establishment of customer behavior in the long run.

Online Consumer Decision-Making Processes

According to the consumer decision-making model (CDP), hotel guests often undergo three key stages before they decide to purchase a good or service. The first one is “need recognition,” whereby they establish why they want to purchase in the first place (Afiouni, Karam & El-Hajj 2013). The second stage involves searching for information, whereby they seek to find alternatives in the market that would allow them to fulfill their desired needs. The third stage of the purchasing process involves the evaluation of alternatives. The three steps of the purchasing process are considered part of a wider cognitive process that explains the decision of customers to make a purchase.

The growth of the internet has affected how the traditional CDP works because it has influenced how customers gain access to information regarding their purchasing decisions. In one study, researchers pointed out that most customers believe the internet influences their decisions to reserve hotel rooms at least 40% of the time (Riley 2015). Since the internet and technological advancements are not static, experts believe that online consumer behavior is set to become more complex (Afiouni, Karam & El-Hajj 2013).

Different factors influence the consumer decision-making process. At the top of the list are economic issues, such as the time spent searching for the best deals online and its associated monetary costs (Riley 2015). The second issue is computing requirements, which encompass search-engine optimization needs and the involvement of online third-party agents in hotel booking (Riley 2015). The last consideration is psychology, which influences how guests undertake their search processes. Based on the multiplicity of these factors, Chen (2014) says it is important to understand the complexity of customer purchasing decisions

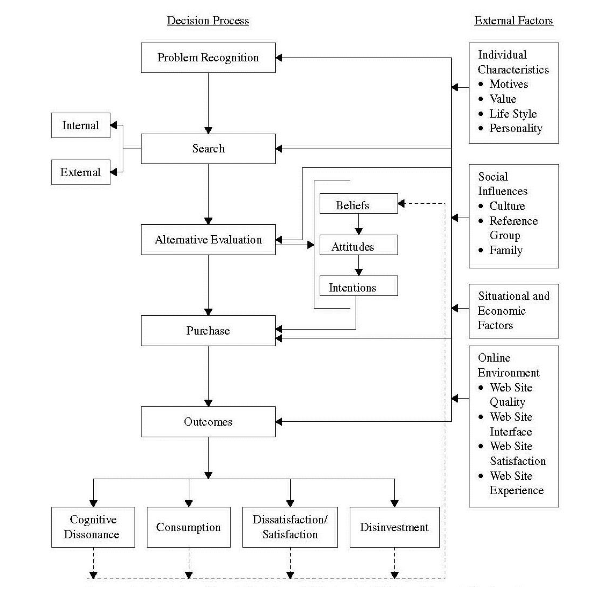

Bambauer-Sachse and Massera (2015) presented a model for understanding online consumer behavior by re-examining traditional CDP. Using his model, the researcher demonstrated that consumer behavior was partly influenced by external factors, including individual characteristics and social influences when making online purchasing decisions (Bambauer-Sachse & Massera 2015). Other contributors to the process include situational and economic factors that influence decision-making processes in the online environment. The diagram below shows the makeup and structure of this model.

According to the diagram above, processes that involve problem recognition, search engine optimization, alternative evaluation, purchase, and outcomes guide the decision-making process. Different external factors support this decision-making process and they include individual characteristics, social influences, situational and economic factors, and the online environment. Generally, these findings show that the consumer decision-making process has evolved into a complex and dynamic system, especially when it is analyzed in the context of the virtual environment.

In terms of making online purchases, Becerra, Santaló, and Silva (2013) contend that a customer’s experience and the heterogeneity of hotel products have the greatest effect. Comparatively, Becerra, Santaló, and Silva (2013) say that many consumers attach both informational and transactional aspects of consumer purchasing decisions to their online booking decisions (especially when evaluating travel products). Although most customers spend a lot of time evaluating existing travel and accommodation options, their decisions are mostly informed by informational aspects of their purchases. Notably, consumers are keen to analyze all existing information before they make their purchases online (Vimi 2013).

Evaluation and Comparison Process

Several researchers have investigated, evaluated, and compared the experiences that customers undergo before making online bookings (Orisys Infotech 2018; Reis & Judd 2014). For example, Dolansky and Vandenbosch (2013) have shown that the process is subject to many individualistic and context-specific factors. Researchers who hold similar views have commonly cited the rational choice theory as an instrumental framework for identifying the right booking options to pursue (Adhikari, Basu & Raj 2013). This theory proposes that the process of evaluating consumer alternatives is premised on their ability to weigh the cost and values of all options available (Orisys Infotech 2018; Reis & Judd 2014).

The same theory postulates that consumers should use rational and logical processes when making their buying choices (Dolansky & Vandenbosch 2013). However, different observers have also pointed out that the consumer buying process is a complex one because it involves emotional cues that affect people’s perceptions of the value of products they intend to buy (Adhikari, Basu & Raj 2013). Many researchers have contextualized these feelings as part of cognitive systems that influence the buying process (McGuire 2015; Bambauer-Sachse & Massera 2015). The same concepts have been highlighted as utilitarian and hedonic shopping values, which affect consumer buying behaviors. They have also dominated consumer research studies by explaining how hotel guests make purchasing decisions (McGuire 2015; Bambauer-Sachse & Massera 2015).

Studies by Falk and Hagsten (2015) have investigated how utilitarian and hedonic values influence consumer perceptions through sales promotions and found that utilitarian benefits are often functional and cognitive, while hedonic values are experiential. The same researchers suggest that customers often use the two types of values when evaluating hotel bookings (Falk & Hagsten 2015). For example, promotional benefits in hotel bookings that convey utilitarian values may appeal to a selected group of customers because they provide monetary savings and increase the value of products they are getting (Falk & Hagsten 2015). Comparatively, promotional campaigns that have hedonic values have emotionally gratifying and emotional benefits.

Some researchers also argue that utilitarian values are associated with consumption utility values (Johnson & Cui 2013). News, anticipation, and memory utility benefits are also associated with utilitarian values. Comparatively, consumption utility is primarily linked to the perceived value consumers get from the consumption or purchase of goods and values (Falk & Hagsten 2015). For example, it could manifest when guests book a hotel room through coupon redemption. Comparatively, news utility refers to the perceived value customers get from receiving timely and informative messages. For example, advertisements for monetary savings fit the description of this type of utility (Falk & Hagsten 2015).

Comparatively, anticipation utility refers to people’s perceived consumption value. For example, desired discounted levels fit this description. Lastly, memory utility refers to customers’ experiences, which often create assimilation effects that could be linked to their current experience of the booking process (Johnson & Cui 2013). At the center of investigations that strive to understand consumer behavior when making online purchases is a growing body of literature that is premised on new and existing theories that have also tried to investigate the same behavior.

Theoretical Analysis

Transaction and Acquisition Utility Theory

Proponents of the transaction theory postulate that consumer behavior is often influenced by several types of activities that have different consequences, depending on the type of decision made (Dixit 2017). The decision-making process is modeled around a framework, which Lee and Jang (2013b) call a “mental accounting system.” Many researchers say the framework is informed by transaction and acquisition utility systems (Dixit 2017). The transaction utility is defined by the difference between the selling and reference prices. Generally, it refers to feelings of pleasure or disappointments that customers may feel when making a deal. Thus, the value of transaction utility largely refers to the ability of customers to understand whether they are getting a good or bad deal through a purchase. Comparatively, acquisition utility refers to the economic value of a transaction.

Transaction and acquisition utility theories have been widely used to understand consumer-buying behaviors. Notably, marketers have used them to understand how different groups of consumers react to different promotional messages. The same researchers have investigated why certain groups of customers do not positively respond to different promotional messages (Hung & Li 2016). Research studies investigating coupon usages have also adopted the two theories to understand how customers perceive purchase values and how they are prone to the deals they make (Dixit 2017).

Nonetheless, researchers such as Lee and Jang (2013a) say traditional theories have failed to explain customer groups that respond well to certain promotional messages, and why they may fail to do so in others. In line with this view, Liang (2014) says customers are often influenced by specific experiences and have different perceived values of products and services when making purchasing decisions. In other words, both utilitarian and hedonic benefits are always in play.

Amaro and Duarte (2015) adopted the transaction utility theory to understand consumer buying behaviors in the online marketplace. The theory was used to understand how customers perceive the value they would get from their online purchases and the nature of their purchase intentions. Their study showed that both monetary and non-monetary values influenced how consumers made their purchasing decisions (Amaro & Duarte 2015). In other words, the two elements were intrinsic motivators to their consumer decisions. Another theory that has been used in a similar context is the goal-setting theory.

Goal-Setting Theory

The goal-setting theory traces its roots in the field of human resource management, where researchers strived to understand the relationship between goal attainment and job performance (Chakrabarti, Barnes & Berthon 2014). This theory postulates that customers’ values and intentions are cognitive processes that influence their behavior. Specifically, the theory encourages the development of goals because it helps people to realize their intended objectives and avoid undesirable outcomes (Chakrabarti, Barnes & Berthon 2014). At the same time, the satisfaction that one gets when achieving a certain goal is the motivation for continuing to pursue them.

The goal-setting theory has been applied in consumer psychology to understand customer-buying behaviors among different groups of consumers. Rong-Da Liang (2014) says that online purchase is an example of goal-oriented behavior among customers. Although many consumers often have a specific desire to pursue a certain goal, their actions normally follow a predetermined behavior, which ultimately contributes to satisfying their desires. Therefore, goal setting is deemed a satisfying behavior that motivates consumers to make specific purchasing decisions.

Theory of Planned Behaviour

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is linked to the goal-setting theory because they both focus on the “expected” value of consumer behavior and actions (Farah 2017). The same analogy is true for the theory of reasons action (TRA). Both models are designed to predict voluntary behaviors, which are influenced by two determinants of human behavior: the attitudes of a consumer when influencing his/her buying decisions, and the social or subjective norms that influence the same buying decisions (Londoño-Roldan, Davies & Elms 2017). The TRA has been further modified to investigate perceived behavioral controls as another determinant of consumer buying behavior. The TPB, which is an extension of TRA, shows how a consumer’s judgment about his/her purchasing decision may ultimately affect the entire purchasing process (Farah 2017). Generally, these insights reveal that a customer’s attitudes, subjective norms, and perceptions of behavior control all have a profound impact on their behavioral patterns of purchasing.

Researchers have used the TPB and TRA theories to examine different social marketing concepts (relating to consumer behavior), but most of their research has been focused on understanding how consumers buy familiar and unfamiliar products (Londoño-Roldan, Davies, & Elms 2017). Several pieces of literature have also shown the efficacy of the theory in the examination of traveler behaviors and destination choices, while others have demonstrated its usefulness in understanding how customers use coupons online and adopt e-commerce (Farah 2017).

TRA and TPB theories largely help us to understand how cognitive processes inform consumer behaviors and how the same models help people to perceive the consequences of making purchasing decisions, which ultimately influence their behavioral patterns. The biggest criticisms voiced against the two theories center on their inability to explain the main causes of the cognitive influences that affect human behavior (Farah 2017). Nonetheless, most studies that have investigated consumer behavior show that it is goal-oriented (Ivanov 2014). The goal-orientation process is defined by people’s quest to attain specific desires and their intention to disassociate themselves with undesirable outcomes.

Van Oest (2013) says that, in an attempt to get what consumers want, they need to trade something of value. For example, consumers have to spend long hours researching the best deals on the internet before they settle for something that they want. Although achieving a specific goal is at the center of consumer purchasing decisions, TRA and TPB models were not inherently designed to accommodate any of these goals. Consequently, the component of goal attainment was ignored in their application. Thus, the two models have not been voiced as viable frameworks for understanding goal-oriented behaviors (Van Oest 2013). They are also weak in describing the psychological processes behind goal intentions.

Model of Goal-Directed Behaviour

Based on the weaknesses of the TRA and TPB models, some researchers developed the model of goal-oriented behavior to understand human purchasing decisions (Li 2015). Like the TRA and TPB models, this framework strives to explain human intention and behaviors when making purchasing decisions. However, these two sets of theories differ on the premise that the model of goal-directed behavior suggests that human intentions are hinged on a volatile desire to achieve a specific goal, while the TRA and TPB do not (Li 2015).

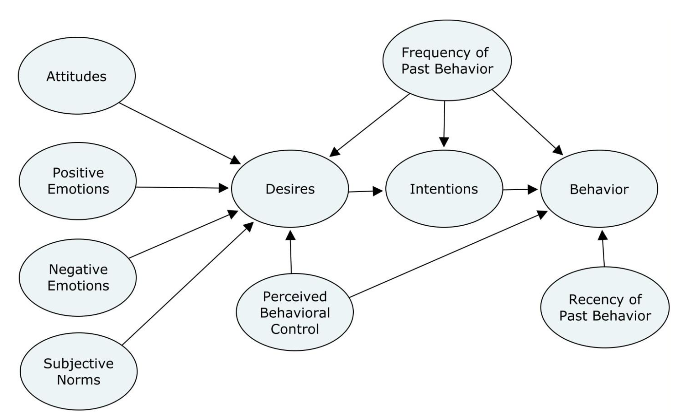

From a psychological perspective, motivation explains an elicit intention by customers to achieve a specific goal by following a particular behavior. Therefore, under the right conditions, a person’s motivation will be ignited, subject to his/her personal beliefs, intrinsic attitudes, and emotions. Consequently, in a customer’s decision-making process, an individual’s motives will be directed towards the achievement of specific intentions. However, the need to do so has to be recognized first. This analysis shows that a specific motive is often targeted towards the achievement of a known intention. Figure 2 below demonstrates the main tenets of the model of goal-directed behavior.

According to the model highlighted above, human desires could be explained using one of three methods: human emotions, subjective norms, and personal attitudes. Human desires play a mediating role in understanding how the three factors mentioned above influence customer purchasing behaviors. Perceived behavior control also has a similar effect. Nonetheless, the model of directed behavior postulates that the nature and frequency of past human behavior significantly affect current consumer behaviors (Chen 2014). An individual’s intentions and future behaviors are also bound to be affected similarly. The concept of “recent past behavior” also postulates that a customer’s current behavior will most likely shape his/her future purchases (Chen 2014). Based on the insights highlighted here, this theory provides a perfect bridge for understanding how human behaviors and intentions interact. In this regard, it accentuates the tenets of the TPB and TRA models because it provides a more powerful explanation of consumer purchasing decisions.

Wearne and Morrison (2013) investigated the role of the goal-directed model in understanding the relationship between the image of a shop and the number of customer visits it registered. The moderating variables were anticipated emotions and desires (Wearne & Morrison 2013). Additionally, the results of the investigation showed that desire and positive emotions were directly correlated to the frequency of customer visits (Wearne & Morrison 2013).

A different researcher investigated the efficacy of the model of goal-directed behavior in understanding customer loyalty standards in a business-to-business context and found that consumer desires were largely influenced by human attitudes and positive anticipated emotions (Chen 2014). Subjective norms were seen to have the same effect as well (Chen 2014). Recent studies have also used the same theory to investigate consumer behavior in the hospitality industry and their findings have revealed that desire is a vital impetus in the intention formation process (Van Oest 2013).

Although the model of goal-directed behavior has been credited for expanding people’s understanding of the relationship between customer attitudes and paradigms, it has not been extensively used in consumer and marketing research. Presently, few research studies investigate how the model affects purchasing decisions in the hotel industry. The current study exploits this research gap by using its salient features to explain consumer behavior and buying intentions. The goal of using this theoretical approach is to provide a holistic framework for understanding the buying behavior of Chinese customers in their hotel booking decisions. The conceptual framework for this investigation appears below.

Conceptual Framework

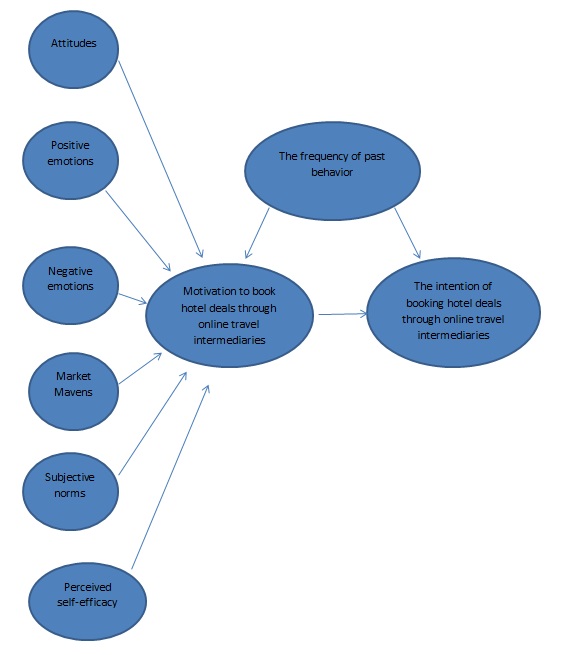

Based on the findings of this study, several pieces of literature have shown that a customer’s motivation to secure hotel deals is partly influenced by his/her attitudes, emotions, market mavens, subjective norms, and perceived self-efficacy (Jang, Tang & Park 2013; Chae, Koh & Prybutok 2014). The frequency of past behaviors also moderates the relationship between customer motivation and the intention to book a hotel. Collectively, these dynamics form the main tenets of the conceptual framework, which outlines the study’s framework of analysis (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill 2007). It appears in figure 3 below.

As seen from the conceptual framework above, the current study will investigate Chinese consumer behaviors by investigating how their attitudes, emotions, market mavens, subjective norms and perceived self-efficacy influence their decision to book hotels (Viglia & Abrate 2014). Past behaviors will also be used as a moderating factor to understand how an intention to reserve a hotel room will translate to a confirmed purchase. This conceptual framework is based on the findings of this literature review.

Summary

This chapter has explored the theoretical and empirical foundations of consumer behavior in contemporary research studies. It has shown that the main models underlying this relationship are the theory of planned behavior, the model of goal-directed behavior, the goal-setting theory, and transaction and utility frameworks. These frameworks have been instrumental in highlighting the main factors influencing consumer-purchasing behaviors.

Key motivating factors that influence their actions have been highlighted in the conceptual framework and they include consumer attitudes, people’s emotions, market mavens, buyers’ subjective norms, and their perceived self-efficacy. Although this literature review explains what other researchers have noted about consumer purchasing behavior, their reviews fail to note how different customer segments respond to the same influences, subject to economic, social, and political contexts. This paper fills this research gap by exploring the behavior of Chinese consumers when making hotel bookings.

Reference List

Adhikari, A, Basu, A & Raj, S 2013, ‘Pricing of experience products under consumer heterogeneity’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 6-18.

Afiouni, F, Karam, C & El-Hajj, H 2013, ‘The HR value proposition model in the Arab Middle East: Identifying the contours of an Arab Middle Eastern HR model’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 1895-1932.

Amaro, S & Duarte, P 2015, ‘An integrative model of consumers’ intentions to purchase travel online’, Tourism Management, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 64-79.

Bambauer-Sachse, S & Massera, L 2015, ‘Interaction effects of different price claims and contextual factors on consumers’ reference price adaptation after exposure to a price promotion’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 63-73.

Becerra, M, Santaló, J & Silva, R 2013, ‘Being better vs. being different: Differentiation, competition, and pricing strategies in the Spanish hotel industry’, Tourism Management, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 71-79.

Buil, I, Martínez, E & Chernatony, L 2013a, ‘Examining the role of advertising and sales promotions in brand equity creation’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 115-122.

Buil, I, Martínez, E & Chernatony, L 2013b, ‘The influence of brand equity on consumer responses’, Journal of Consumer Marketing, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 62-74.

Chae, H, Koh, C & Prybutok, V 2014, ‘Information technology capability and firm performance: contradictory findings and their possible causes’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 305-326.

Chakrabarti, R, Barnes, B & Berthon, P 2014, ‘Goal orientation effects on behavior and performance: evidence from international sales agents in the Middle East’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 317-340.

Chen, H 2014, Consumer behavior of hotel deal bookings through online travel intermediaries. Web.

Chiu, H & Chen, C 2014, ‘Advertising, price, and hotel service quality: a signaling perspective’, Tourism Economics, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 1013-1025.

Dixit, S 2017, The Routledge handbook of consumer behavior in hospitality and tourism, Taylor & Francis, London.

Dolansky, E & Vandenbosch, M 2013, ‘Price sequences, perceived variability, and choice’, Journal of Product and Brand Management, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 314-321.

Falk, M & Hagsten, E 2015, ‘Modelling growth and revenue for Swedish hotel establishments’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 59-68.

Farah, M 2017, ‘Application of the theory of planned behavior to customer switching intentions in the context of bank consolidations’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, vol. 35, no. 1, pp.147-172.

Hua, N, Morosan, C & DeFranco, A 2015, ‘The other side of technology adoption: examining the relationships between e-commerce expenses and hotel performance’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 109-120.

Hung, K & Li, X (eds.) 2016, Chinese consumers in a new era: their travel behaviors and psychology, Routledge, London.

Ivanov, S 2014, Hotel revenue management: from theory to practice, Zangador, New York, NY.

Jang, S, Tang, C & Park, K 2013, ‘The marketing-finance interface – a new direction for tourism and hospitality management’, Tourism Economics, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 1197-1206.

Johnson, J & Cui, A 2013, ‘To influence or not to influence: External reference price strategies in pay-what-you-want pricing’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 66, no. 2, pp. 275-281.

Lee, S & Jang, S 2013a, ‘Asymmetry of price competition in the lodging market’, Journal of Travel Research, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 56-67.

Lee, S & Jang, S 2013b, ‘Is hiding fair? Exploring consumer resistance to unfairness in opaque pricing’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 434-441.

Li, X (ed.) 2015, Chinese outbound tourism, CRC Press, New York, NY.

Liang, A 2014, ‘Exploring consumers’ bidding results based on starting price, several bidders and promotion programs’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 80-90.

Londoño-Roldan, J, Davies, K & Elms, J 2017, ‘Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior to examine the role of anticipated negative emotions on channel intention: The case of an embarrassing product’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 8-20.

McGuire, K 2015, Hotel pricing in a social world: driving value in the digital economy, John Wiley & Sons, London.

Monga, N & Kaplash, S 2016, ‘To study consumer behavior while booking a hotel through online sites’, International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 158-164.

Orisys Infotech 2018, Trends in the hotel & travel industry booking and consumer behavior. Web.

Reis, H & Judd, C 2014, Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology, 2nd edn, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Riley, C 2015, Hotel bookings: research shows two major booking behavior changes rising among guests. Web.

Rong-Da Liang, A 2014, ‘Exploring consumers’ bidding results based on starting price, number of bidders and promotion programs’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 80-90.

Saunders, M, Lewis, P & Thornhill, A 2007, Research methods for business students, 4th edn, Prentice Hall, Harlow, EN.

Van Oest, R 2013, ‘Why are consumers less loss averse in internal than external reference prices’, Journal of Retailing, vol. 89, no. 1, pp. 62-71.

Viglia, G & Abrate, G 2014, ‘How social comparison influences reference price formation in a service context’, Journal of Economic Psychology, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 168-180.

Vimi, J (ed.) 2013, Cases on consumer-centric marketing management, IGI Global, New York, NY.

Wearne, N & Morrison, A, 2013, Hospitality marketing, Routledge, London.