Health equity is the long-lasting theme of discussion within the research community. Numerous studies have analyzed the disparity in the health sector through various lenses, but the correlation between quality of life and people’s living displacement became a subject to a recent debate. In many cities around the United States, certain areas’ average life expectancies are 20-30 years lower than those living in mile proximity (Graham 2016). This fact opens a new direction for the discussion of the residence environment and healthcare.

The research from Atna Foundation has found that such disparity is evident across multiple geographies. The average life expectancy for babies delivered to mothers in New Orleans varies by up to 25 years between communities just a few miles apart (Graham 2016). Newborns in Montgomery County, Maryland, and Arlington and Fairfax Counties, Virginia, may expect to live 6–7 years longer than babies born in the District of Columbia (Graham 2016). Life expectancy in Roxbury, Massachusetts, is 59.9 years, but it is 91.9 years in the Back Bay district, which also stands a few miles away (Graham 2016). This data is not surprising considering an unequal distribution of healthcare professionals across the US borders and the environmental conditions of different neighborhoods. The impact of a zip code on the health of its residents is multifaceted. A citizen’s health is directly influenced by where the residence in a variety of ways, from air pollution and contaminants to the availability of healthy products for consumption, nature, and medical treatment. However, it is also a subtle signal of socioeconomic characteristics, such as race and wealth, that are linked to health and lifespan.

Projection of the healthcare workforce at a national level, particularly in primary care, hides significant regional variance. Some places struggle to offer basic healthcare services, while others have a surplus of professionals (Naylor et al. 2019). The high concentration of providers in urban and/or wealthy regions, contrasting with a relative undersupply in rural and/or low-income areas, is a typical condition within the United States (Naylor et al. 2019). The spread of surgical services in the United States exemplifies this point. Similarly, as cities become more urbanized, the number of primary care physicians rises, from 39.8 per 100,000 population in non-metropolitan regions to 53.3 in big center metropolitan areas (Naylor et al. 2019). Recruiting, career development possibilities, financial incentives, infrastructure and personnel, workload and autonomy, and the professional work environment are all factors that influence the choice of physicians’ practice.

Analysis of Healthcare Data

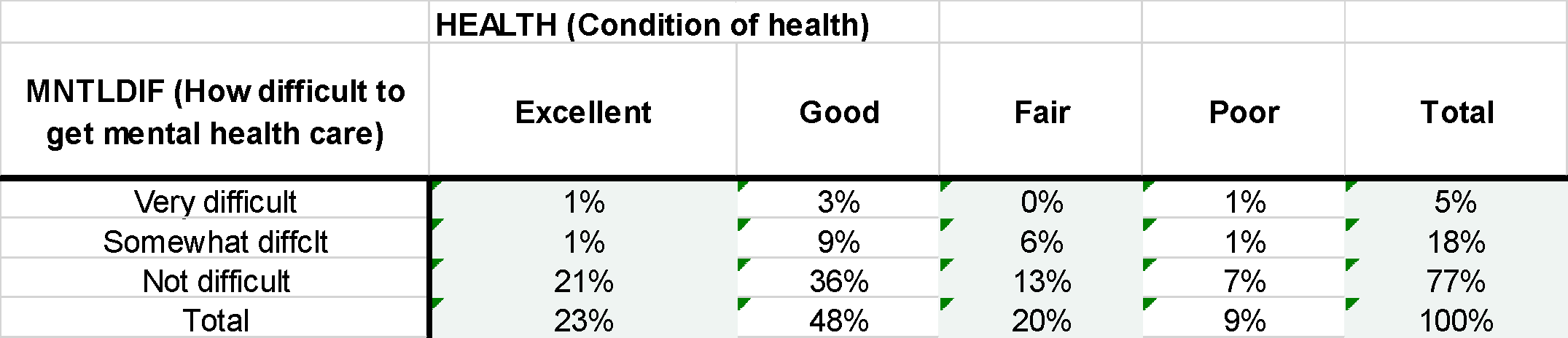

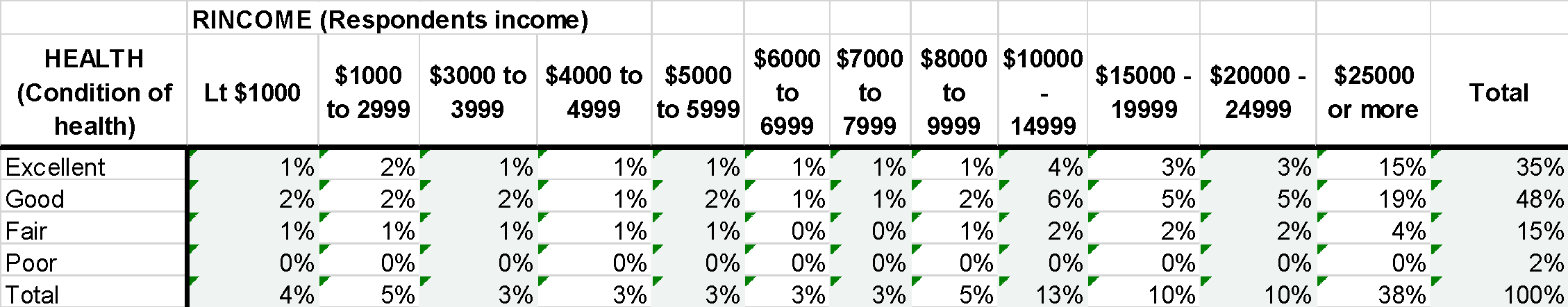

The health of the American community is interdependent with access to healthcare facilities. The analysis of GSS data in Table A demonstrates a correlation between the difficulty to access mental health care and personal health. The respondents were asked to answer a question “Would you say your own health, in general, is excellent, good, fair, or poor?” As it is evident from the table, the majority of respondents characterized the difficulty to access mental health care as “not difficult” — 77%, among those over 57% of respondents that consider their health as good or excellent. The review of respondents’ income and condition of health in Table B could indirectly point to the interconnectedness of access to healthcare facilities. 38% of respondents stated their income in 1997 to be over $25000. This population segment also accounts for most people that perceive their health to be of higher quality. The analysis of these variables could help further knowledge in the social sciences by providing the direction for leveling possible causes for the disparity in quality of life.

References

Graham, Garth N. 2016. “Why Your ZIP Code Matters More than Your Genetic Code: Promoting Healthy Outcomes from Mother to Child.” Breastfeeding Medicine 11(8): 396–97.

Naylor, Keith B., Joshua Tootoo, Olga Yakusheva, Scott A. Shipman, Julie P. Bynum, and Matthew A. Davis. 2019. “Geographic Variation in Spatial Accessibility of U.S. Healthcare Providers.” PLOS ONE 14(4).