Executive Summary

The area of recruiting and staffing was chosen for the analysis of recent trends and subsequent provision of recommendations for change. First, talent management strategies were recommended, such as creating a talent pool and identifying talent needs in the current operation. Second, it was established that mutually perceived trustworthiness is an important factor in the relationship between an applicant and a hiring organisation, which is why it was recommended to monitor the quality of the information provided by the organisation to applicants. Third, several practices were identified and described that should be avoided in the interviewing process. Finally, the ethical boundaries of searching for applicant information that recruiters should consider were defined.

Introduction

Like other areas of human resources management practice, the area of recruiting and staffing is constantly revised today. Due to technological development as well as advancements in management in general, human resources management practitioners face various needs related to improving their practices. For an organisation, it becomes crucial to be innovative in terms of its human resources management practices, and such innovation is impossible without proper research and information analysis (Bratton & Gold 2012).

To improve organisational practices related to recruiting and staffing, it is necessary to review recent trends and themes in this area, and such themes include talent management principles, trustworthiness, widespread interviewing mistakes, and searching for applicant information online.

Literature Review

Principles of Talent Management

For businesses today, it is of paramount importance to attract creative employees who are capable of not only complying with their job descriptions but also making extra contributions to their work. Within recent decades, the concept of talent management has been developed in this context, and many academics and professionals have addressed the issues of how talented employees can be recruited and how it can be ensured that an organisation gains maximum benefits from their talents.

Stahl et al. (2012) collected primary data in a series of in-depth case studies with 37 international corporations. The inclusion criteria were the organisations’ large scope of an international operation, established reputation, and successful long-term performance.

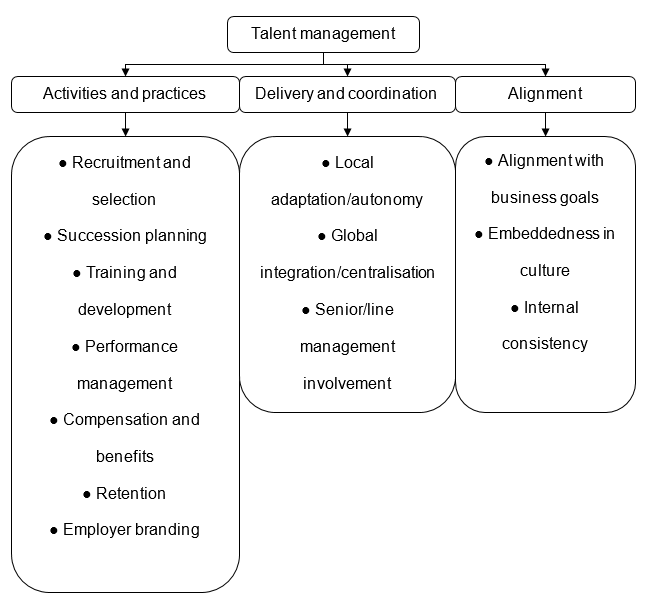

The authors further analysed various themes that emerged from the responses of those organisations’ representatives. It was primarily established that the area of talent management incorporates three major components: activities and practices, delivery and coordination, and alignment (Figure 1). In compliance with the CIPD guidelines (Talent management 2017), Stahl et al. (2012) emphasise the importance of embedding talent management principles in the value system of a firm; i.e., talent management should be part of the corporate culture and ethics.

In the context of the issue of interest; i.e., recruiting and staffing, talent management starts with the process of identifying the areas of an organisation’s operation that require specific talents. From this perspective, a firm should not merely hope that a talented employee will contact them, be hired, and improve internal processes with his or her exceptionally excellent skills and abilities. Instead, a firm should plan its staffing by identifying job positions and specific responsibilities that need to be filled with and performed by talented employees, respectively, and the essence of the expected talented should be defined.

The key consideration in this regard is that a position and a person who is to fill this position are properly prepared for one another, and necessary adjustments are made to ensure that maximum performance can be expected. The respondents in the study conducted by Stahl et al. (2012, p. 30) referred to this consideration as ‘the right people in the right place,’ and the cultural fit was a major criterion for assessing the effectiveness of staffing.

Concerning recruitment, various approaches were proposed by the respondents. The approach referred to the most was the talent pool strategy: based on this, companies recruit ‘the best people’ (Stahl et al. 2012, p. 29) and later place them into positions based on current staffing needs. This strategy is seen by multinational corporations as a more flexible one compared to the approach in which a specific person is recruited for a specific position; having a talent pool, a firm can more easily make adjustments to its operation because it knows that its workforce is capable of handling the change.

Concerning the channels of recruitment, some authors have proposed to extensively use social networking services (Micik & Eger 2015). This approach complies with the recommendation proposed by Stahl et al. (2012) to employ modern technologies in various aspects of talent management, including recruitment and staffing.

Trustworthiness

A specific perspective on the process of recruiting was adopted by Klotz et al. (2013): the perspective of trustworthiness. Various academic and professional studies (the former include research sources, and the latter include professional websites and best practice sources) have noted that applicants’ and hiring organisations’ perceived trustworthiness of one another is a factor in the recruitments and selection processes.

However, no studies before the one conducted by Klotz et al. (2013) had explored the notion specifically in an integrated manner. The authors primarily address the process of information exchange: applicants and hiring organisations exchange large amounts of information, and successful recruitment- and selection-related outcomes can only be expected in case both parties perceive the information they receive as relevant, accurate, and complete. Interestingly, the study focuses not only on the hiring organisations’ processing of information but also on the applicants’, while the latter perspective is often overlooked in human resources research.

The authors generally conclude that a high level of thrust between applicants and hiring organisations is needed in order to not only make the recruitment and selection processes smoother but also make it more effective. Interestingly, Klotz et al. (2013, p. S116) discovered that ‘[i]nterviewers with a high propensity to trust [were] more effective at correctly detecting dishonest (i.e., low integrity) interviewees than interviewers with low trust propensity.’

Although the conclusion is counterintuitive, as it suggests that trusting people more helps one avoid being deceived, it has been confirmed in academic research in the area of human resources management. In compliance with this conclusion, Walker et al. (2013) suggest that the lack of trust toward the applicant can prevent organisations from sustaining effective recruitment practices.

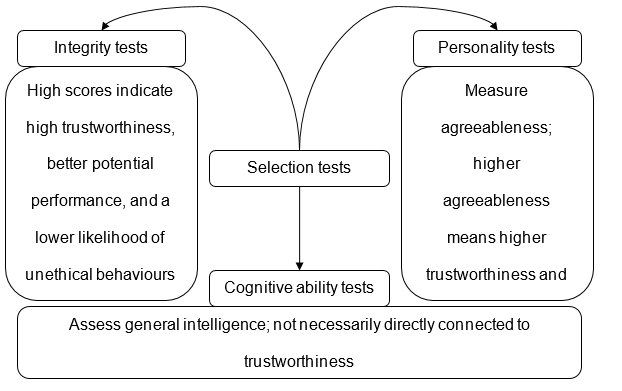

It is important to note that trustworthiness is a factor, the importance of which does not decrease after the pre-entry period. The relationship of mutual trust established during the recruitment and selection processes will further affect the way a hired employee adapts to the working conditions and performs. Klotz et al. (2013) propose various selection tests that can be administered by recruiters to assess the trustworthiness of applicants (Figure 2).

Moreover, the very process of administering selection tests further develops the applicant’s perceptions of hiring organisations’ trustworthiness and professionalism. In compliance with these conclusions, the CIPD refers to the role of trustworthiness in leadership (Experiencing trustworthy leadership 2014). In this context, it is recognised that leaders are competent (i.e., capable of leading people) only if their potential followers trust them and express readiness and willingness to be led. Therefore, if an applicant initially develops a perception that the hiring organisation is not fully truthful during the recruitment period, he or she can be expected to perform worse as an employee at the organisation than he or she could perform if the organisation were perceived as trustworthy.

It is evident that, in their recruiting and staffing efforts, organisations should ensure that the information provided to applicants is accurate and complete. Also, organisations should trust applicants and consider any information provided by the accurate and complete as well. However, it does not mean that organisations are not entitled to search for additional information (Sánchez Abril, Levin & Del Riego 2012); quite the opposite, the processes of collecting and processing relevant information play a pivotal role in virtually any area of human resources practice.

Interviewing Pitfalls

Interviewing is arguably the central element of the recruiting and staffing processes because an interview is a moment at which critical information is collected, and further decision making will be largely based on this information. Many academic and professional research findings are dedicated to best interviewing practices (Harrison 2013); however, to ensure that the interviewing process is effective, a recruiter should review not only recommendations as per practices to which it is necessary to commit but also recommendations as per practices that should be avoided. Arthur (2012) addresses the latter category of practices, and valuable conclusions can be drawn from the author’s suggestions.

First of all, an applicant should not be interrupted by the recruiter. As it was established above (2.2. Trustworthiness), it is important that the information supplied by the applicant to the hiring organisation represented by a human resources manager (as well as information supplied by the organisation to the applicant) is not only accurate but also complete. Therefore, applicants should not be deprived of an opportunity to say everything they want to say unless what they say is blatantly irrelevant.

Second, it is not a favourable practice for a recruiter to either agree or disagree with an applicant; instead, it is recommended to ‘express interest and understanding’ (Arthur 2012, p. 197). Further, a recruiter should not try to impress an applicant (e.g., with the intention to build a perception of the hiring organisation as professional) by using terminology that the applicant may not know. Instead, understanding between the two parties should be pursued.

The author specifically stresses that the interviewing process is applicant-centred despite the fact that it may feature delivery of the hiring firm-related information. This is why the recruiter should not talk about himself or herself and should encourage the applicant to be more actively engaged in the process as opposed to merely answering questions. For example, welcoming questions from an applicant about the hiring organisation is a favourable practice; however, it is important to avoid a situation in which an applicant starts interviewing a recruiter; in this case, the effectiveness of the data collection process for the recruiter is decreased (Selection methods 2016).

Although much attention has been paid to the body language, Arthur (2012) recommends avoiding hasty decisions based on an applicant’s body language signs because such signs fall into the category of first impressions. First impressions can be misleading, and this is especially true if the recruiter’s possible biases and lack of proper information are taken into consideration.

In compliance with these recommendations, Armstrong and Taylor (2014, p. 99) recommend ‘avoid[ing] intrusive and hectoring questions in interviews.’ It is also stated that an applicant should not be criticised or compared to any employees of the hiring organisation (current, former, or prospective). In general, a recruiter should approach the process of interviewing as data collection first of all and should stay focused on receiving any information that can be further used to achieve recruiting and staffing goals.

Further Search for Information

Although interviewing is a data collection process in the framework of recruiting and staffing, a human resources manager does not necessarily stop data collection and turns to data analysis immediately after the interview. In recent years, academics and professionals have been paying more and more attention to the way recruiters further seek relevant applicant information. In this context, a particular practice that should be discussed is looking applicants up online and, especially, examining their profiles in social networking services. Slovensky and Ross (2012) argue that there are both advantages and disadvantages of this approach to collecting applicant information.

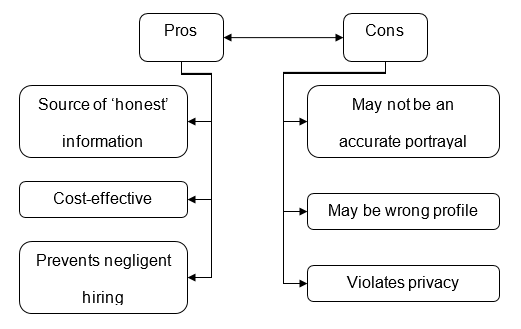

The authors suggest that the practice cannot be seen as fully effective and positive or fully inappropriate and harmful (Figure 3). If human resources managers wish to consider the information they obtain from applicants’ social media accounts, proper strategies should be designed to ensure that the practice complies with relevant ethical principles.

First of all, as it was established above (2.2. Trustworthiness), recruiters should trust applicants, and this implies that recruiters should consider the information provided by applicants relevant, accurate, and complete. However, it was also established that searching for additional information is not a reprehensible practice. In fact, Stevens (2013) confirms that the CIPD recommends practitioners to use various tools to ensure that hiring a particular person will not damage the hiring organisation, and relevant information in this regard can be found in social networking services. At the same time, the Institute warns human resources managers that there are factors of ethics in this data collection practice.

Specifically, if disclosing certain information found by a recruiter about an applicant online can violate the applicant’s privacy, the recruiter should refrain from supplying such information to other managers. Also, if the applicant is not informed by the recruiter that social media profile checks are carried out and is not given an opportunity to respond to the recruiter’s findings (Stevens 2013), the CIPD states that the recruiter’s actions may be regarded as illicit. In this case, legal complications for the hiring organisation may follow.

Slovensky and Ross (2012) conclude that, before making the decision to consider social media as a source of information in the selection process, human resources managers should ensure that it is possible to collect relevant information via social networking services in the given case and it is, moreover, necessary to do so in order to avoid negative outcomes for the hiring organisation. At the same time, applicant information obtained from social media should not be regarded as the main source of data, on which the decision-making process will be ultimately based.

Instead, the primary source of information is the applicant himself or herself, as he or she provides relevant information directly to the recruiter according to the latter’s inquiries. Therefore, the use of guidelines on how to assess an applicant based on his or her behaviours online, such as the guidelines provided by Stoughton, Thompson, and Meade (2013), are not considered compliant with best practices in human resources management.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Four issues in recruiting and staffing as an area of human resources management practice have been addressed: how talents can be attracted, how trust between applicants and hiring organisations can be gained and granted, how the interviewing process should be organised and conducted (and how it should not), and how the additional search for applicant information can be performed. Conclusions drawn from the review of literature allow providing important recommendations to the organisation’s management and leadership as well as to the human resources management departments; these two parties are identified as major stakeholders from the perspective of the presented business report.

First of all, it is recommended to adopt the talent pool strategy along with the talent needs identification approach. This way, the organisation will be able to hire people of various talents and later apply their talents to areas, in which specific professional needs are defined. Although seemingly separate processes, recruiting talents and identifying needs for talents in the existing job positions are highly interconnected, and this is why it is recommended that one person or one team of people are assigned to perform these talent management activities.

Second, it is recommended to modify the way information is exchanged between applicants and recruiters. Applicants’ information should be trusted and considered accurate and complete; for its part, the hiring organisation should ensure that it provides accurate and complete information, too, and strives for gaining potential employees’ trust as opposed to trying to impress them or show them how professional the organisation is.

Third, it is recommended that recruiters commit to the prescribed interviewing practices; particularly, avoid such practices as asking irrelevant questions, letting applicants ask such questions, or letting applicants control interviews. Finally, recruiters should commit to ethical behaviours (avoiding breaches of privacy) in terms of collecting any applicant information that is not delivered by applicants themselves. It can be expected that following these recommendations will make the organisation’s recruiting and staffing processes not only more compliant with standards but also more effective.

Reference List

Armstrong, M & Taylor, S 2014, Armstrong’s handbook of human resource management practice, 13th edn, Kogan Page Publishers, London.

Arthur, D 2012, Recruiting, interviewing, selecting & orienting new employees, 5th edn, American Management Association, New York, NY.

Bratton, J & Gold, J 2012, Human resource management: theory and practice, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Experiencing trustworthy leadership. 2014. Web.

Harrison, SR 2013, ‘Cream of the crop: interviewing and selecting for success’, Thomas M. Cooley Law Review, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 107-128.

Klotz, AC, Motta Veiga, SP, Buckley, MR & Gavin, MB 2013, ‘The role of trustworthiness in recruitment and selection: a review and guide for future research’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. S104-S119.

Micik, M & Eger, L 2015, ‘Recruiting talents with social media’, Actual Problems in Economics, vol. 165, no. 1, pp. 266-274.

Sánchez Abril, P, Levin, A & Del Riego, A 2012, ‘Blurred boundaries: social media privacy and the twenty-first-century employee’, American Business Law Journal, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 63-124.

Selection methods. 2016. Web.

Slovensky, R & Ross, WH 2012, ‘Should human resource managers use social media to screen job applicants?’, Managerial and Legal Issues in the USA, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 55-69.

Stahl, G, Björkman, I, Farndale, E, Morris, SS, Paauwe, J, Stiles, P, Trevor, J & Wright, P 2012, ‘Six principles of effective global talent management’, Sloan Management Review, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 25-42.

Stevens, M 2013, CIPD launches guide to vetting candidates on social media. Web.

Stoughton, JW, Thompson, LF & Meade, AW 2013, ‘Big five personality traits reflected in job applicants’ social media postings’, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, vol. 16, no. 11, pp. 800-805.

Talent management. 2017. Web.

Walker, HJ, Bauer, TN, Cole, MS, Bernerth, JB, Feild, HS & Short, JC 2013, ‘Is this how I will be treated? Reducing uncertainty through recruitment interactions’, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 56, no. 5, pp. 1325-1347.