Introduction

Humanitarian actions depend on the evidence-base greatly because required policies and responses cannot be developed effectively and ethically without solid ground (International Initiative for Impact Evaluation, 2016). Both the amount of knowledge and its quality are critical because “the international humanitarian community’s ability to collect, analyse, disseminate and act on key information is fundamental to effective response” (Clarke & Darcy, 2014, p. 5). In addition to that, such approach ensures professionals’ impartiality and delivery of the best interventions. Finally, the evidence is needed to ensure involved parties that resources were utilised efficiently and benefited vulnerable populations.

However, the evidence-base in international disasters and humanitarian crises fails to be as strong as expected. The accountability and effectiveness of humanitarian actions are poorly considered, which affects interventions and makes them less effective. Humanitarians fail to discuss evidence generation as a continuous process and often have problems with the consistent use of research methodologies. They do not pay enough attention to the direct interaction with vulnerable populations, which prevents them from meeting people’s needs (Wong, 2011). As a result, the effectiveness of humanitarian actions is affected adversely so that expected outcomes are not reached.

There is also a problem in the framework of accountability because stakeholders do not receive sufficient evidence that reveals how resources were utilised and what results were observed (ALNAP, 2015). Realising the existence of this issue, this paper will discuss the current state of the evidence-base for the accountability and effectiveness of humanitarian actions. It will pay attention to those problems that are often faced in the framework of Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance (ALNAP) (Polastro, 2014). Finally, some recommendations will be made on how to resolve them. Thus, strategies that should be used by humanitarians in order to increase the strength of the evidence-base will be described.

Accountability

Failure to create and utilise evidence effectively often leads to the lack of accountability. In general, the stakeholders of the humanitarian actions that include donor organisations, affected parties and civil society are willing to receive information which can prove how the resources allocated for assistance were used. They need to have access to the data that reveals how money was allocated and also to find out what outcomes were reached. In order to meet their expectations, professionals who deal with humanitarian assistance should present the information about their operations on a routines basis. Thus, they should not only prove that the needs they focus on are real but also reveal that the responses they made were the most effective and efficient ones. It is critical to ensure stakeholders that all choices and decisions were thoroughly considered and well-grounded. Professionals started to pay their attention to these issues in the 1990s, so that a wide range of technical initiatives has been already successfully implemented, and the quality of information as well as assessment mechanisms improved (Basher, 2015). Still, the base of evidence for those approaches that work successfully lacks accountability even today.

Technology is believed to provide a lot of improvement possibilities, but it also presupposes challenges. For example, data protection can turn into an obstacle. The Humanitarian Accountability Partnership that deals with the accountability of individuals who require humanitarian assistance should bear in mind that geo-tagging affects people’s privacy while digital recording also entails complications connected with the necessity to deal with large amounts of data. In addition to that, this organisation reveals one more issue and notices that beneficiary engagement is “extremely rare in an evaluation, even if the current trend is to push for beneficiary involvement at this stage” (Alexander, Darcy, & Kiani, 2013, p. 29).

Agencies that provide humanitarian aid often operate in those contexts that are politicised and insecure, which means that the allocation of assistance is not impartial but affected by the political goals. Taking this fact into consideration, it is significant for them to prove stakeholders that the resources were used as promised, which is not maintained currently. The difference between the quality and quantity of required and provided aid is also rarely provided, which proves the existence of accountability deficit (Featherstone, 2013).

Roddy, Strange, & Taithe, (2015) discussed humanitarian aid accountability in Great Britain at the end of the 19th century – beginning of the 20th century. They emphasised that even at that time crucial self-regulation in this sphere were maintained with the help of the press. Still, Arroyo (2014) refers to the 2010 Haiti Earthquake to prove that today there is a gap in this process. Professional underlines that International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs) fail to provide affected populations with the information about humanitarian operations. Even though these organisations implemented some mechanisms recommended by the Humanitarian Accountability Partnership, Haitians had very limited ability to receive an expected response.

The research revealed that “while in principle agencies have the best interests of affected populations as their aim, fragmentation and power asymmetries within the humanitarian sector create conditions wherein agencies define the limits of what they are responsible for and, consequently, what they can be held accountable for” (Arroyo, 2014, p. 110). Thus, humanitarians’ recognition of the responsibility is critical because it is the main element that ensures efficient implementation of initiatives and accountability enhancement. What is more critical, Tan and Schreeb (2015) claim that there is no internationally accepted definition of accountability that could be used by professionals as the basis.

Effectiveness

The most critical thing that is discussed in the framework of humanitarian assistance is its effectiveness because the very purpose of this aid is crucial as it deals with the lives of the affected populations. The effectiveness of the humanitarian aid can be considered when measuring the way provided assistance fulfilled the needs of the population and met agencies’ targets. In this way, it is important for donors to monitor who receives their money and how they are spent (Clarke & Darcy, 2014).

For the evidence to be effective, it should be of high quality. This characteristic can be ensured if such dimensions are taken into consideration as:

- Accuracy: the evidence should correspond with the real events. It should reflect the situation with no changes and include true to life measurements;

- Representativeness: professionals should do their best to ensure the connection between the representative of a group and the group itself so that the condition of one person can reflect the larger population;

- Attribution: the analysis should reveal connection between conditions or events so that the results of an action can be discussed;

- Generalizability: evidence should ensure the possibility to respond to different situations on its basis;

- Clarity: all information regarding the source of the evidence, the reason and the time when it was collected should be available (ALNAP, 2016).

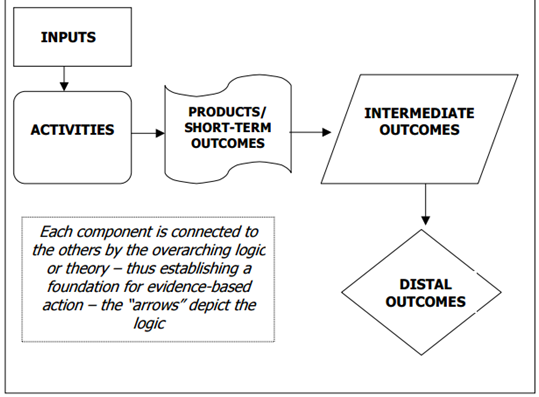

From the nursing perspective, the problems in the evidence-base can be solved when referring to the logic models offered and successfully utilised by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Using the basic program logic model as an example and a starting point, humanitarians can have an opportunity to improve their evidence and outcomes reached (see Fig. 1).

Birnbaum, O’Rourke, Loretti, and Daily (2014) believe that following an appropriate model, professionals can have an opportunity to deal with the principal branch of disaster research. They connect successful intervention with the effective evidence and believe that having high-quality data humanitarians can “(1) decrease the human, environmental, and economic losses; (2) decrease morbidity; (3) decrease pain and suffering; and (4) enhance the recovery of the affected population” (Birnbaum et al., 2014, p. 1). The guideline provided by Kulling, Birnbaum, Murray, and Rockenschaub (2010) should also be utilised.

Of course, humanitarian aid turns out to be rather effective in the majority of cases. It influences an adverse situation significantly, providing the recipients with the opportunity to improve the quality of life for affected populations. If such outcomes were not reached, there would be no sense in the continuation of these procedures. However, some challenges are still faced by humanitarians and other stakeholders. Humanitarians can hardly assess the success of their actions because they face problems with reaching affected populations. Increasing the number of attacks does not allow professionals to increase the relevance of aid and its effectiveness (Featherstone, 2013).

Trying to attract humanitarians’ attention to the problems connected with the poor evidence-base, Lam, Torres, Zoleveke, and Ondrusek (2016) presented a report about the response to Category 5 Tropical Cyclone (TC) Winston that hit Fiji. Professionals noticed that the communication between involved organisations sometimes led to confusions and misunderstanding, which means that there was no opportunity to obtain high-quality evidence. Even though the aid was delivered immediately and assisted the population, problems with the usage of assessment tools were reported. There were numerous new elements that were unknown to the agencies because they had no effective evidence-base that could be used to obtain required information and share knowledge obtained in practice. The human resource also occurred be a problem. Personnel turnover prevented involved parties from receiving required information and lead to operational issues (Lam et al., 2016).

In this way, reports provided by ALNAP do not only reveal successful operations and best practices that allowed humanitarians to provide required care but also identify spheres that require immediate improvement. Smith and Flatt (2011) believe that effective evidence can ensure appropriate allocation of financial aid and non-profit assistance. But professionals are not able to work efficiently because they lack evidence. Parties involved in these processes fail to cooperate effectively. They have no network that can be used to share knowledge and search for important data. The existing evidence-base is poor, and it does not include the information obtained directly from the affected populations, which means that professionals are not able to check whether their goals are well-aligned with the recipients’ needs. Thus, evidence that is available lacks quality and strength, which is a great drawback that proves that there is a necessity to implement new strategies to enhance the situation.

Strategies that Could Help to Raise the Strength of the Evidence-Base

For humanitarian aid to be properly planned and allocated, it is critical for professionals who deal with programming to have good evidence as the basis. That is why organisations within the humanitarian system do their best to improve and strengthen the evidence-base. It would be advantageous if this sectors robust methodology, efficiency, collaboration, continuity, and concentrate on inclusion and ownership.

A lot of information that is used as evidence when discussing humanitarian issues is obtained from research studies conducted with the help of qualitative methods. Unfortunately, the selected methodology is often poorly understood and applied, which means that agencies need to improve this area and became more rigour. In addition to that, limitations can be overcome if a mixed method is used to develop evidence because it was generated to fill the gaps of the separate ones. To ensure the strength of evidence, humanitarian actors should be encouraged to describe their methodology in the research paper. In this framework, it is also significant to make organisations cooperate.

They should share knowledge and experiences of the usage of qualitative and quantitative methodologies (Chan & Burkle, 2013). For such a purpose, special networks or inter-organisational groups can be used. ALNAP or ACAPS, for example, can synthesise the best practices in the sphere and provide training materials created on their basis. It will be beneficial if bodies for quality assessment are established. They can check whether reviews meet all need requirements and are trustworthy. Thus, humanitarian organisations should pay more attention to research methodology. They need to encourage and promote strategic partnership and training so that the gaps in this area can be filled. The standard of evidence creation should be enhanced so that it becomes stronger.

Taking into consideration the fact that the process of evidence gathering is resource-consuming, it is significant to prove that time and money are used efficiently (Scott, 2014). Donors and humanitarian organisations need to consider whether the benefits obtained from the results exceed overall expenditure. It will be better if they are both direct and long-term because more substantial improvement can be made in this way (Blanchet & Martin, 2011).

The effectiveness of the evidence and its quality can be affected greatly by the collaboration between the organisations that operate in the humanitarian system (Akl et al., 2015). It will be better if they pay more attention to the verification procedures and implement efficient cross-checking and quality control. What is more, it is significant to implement initiatives that can ensure their readiness to undertake responsibility. Donors should cooperate to identify the best ways to fill the evidence gaps that exist within the humanitarian system. They can use inter-agency networks and platforms to reach one another without any complications. In addition to that, they should develop international standardised frameworks for assessment and evaluation (ALNAP, 2012; Curmi, 2013). The collection of evidence should be maintained when budgets are considered, and the usage of system bodies (such as ACAPS and ALNAP) maximised.

One more sphere for the improvement of the evidence-base deals with continuity. The thing is that evidence generation is usually treated as a short event but not a long lasting process. As a result, it is obtained episodically and its effects over time are not discussed appropriately (DARA, 2013). This drawback also occurs because of the high personnel turnover rates that are observed in many spheres today. Such gaps can be filled if humanitarians utilise assessment and monitoring systems that strengthen one another.

As a rule, those individuals who deal with humanitarian actions pay little attention to the way data is collected and generated. Being affected by a crisis, they are more targeted at the immediate reaction. That is why, they rarely ask questions about the issue and obtain the information not from the participants of the event but from the international organisations, so they tend to meet their needs but not those of the particular populations. During assessments, they find out what aid is needed with no prioritising. In a similar way, the results of the assessment tend to be not very critical.

Trying to find out whether some even is a crisis or not, humanitarians do not really use the answers of the involved people as the basis and refer to the organisational views. Thus, it is critical to ensure that humanitarian organisations pay more attention to the reasons why they collect data and who it is for. They need to consider the usage of civil society organisations and involvement of the affected population in the process of data gathering. Humanitarian actors should reveal local knowledge and its connection with the recommendations clearly (Clarke & Darcy, 2014). It is critical to approach informed consent and inform participants on how the information they provided was used and what decisions were made in regard to it.

In this way, it is also significant to make sure that important evidence is used during humanitarian decision-making because the lack of attention paid to the needs assessment, for example, can lead to adverse effects made on the individuals affected by disasters. So professionals who create evidence should consider the accessibility of the information, timeliness, circulation through media and clear steps of decision-making procedure that can ensure that evidence can be successfully implemented for some incentives (Bradt, 2009).

Conclusion

To provide humanitarian assistance, professionals need to gather appropriate evidence because, being based on it, actions are more likely to be effective and accountable. They need to pay much attention to the evidence-base greatly because with its help they can ensure positive outcomes and appropriate actions. Humanitarians need to consider the amount of evidence and its quality because it should be enough to use for an efficient decision-making regarding a large population. Professionals should be impartial for them to be able to allocate aid appropriately. Using the information from the evidence-base, they can benefit vulnerable populations. Still, existing gaps prevent humanitarian agencies from utilising strong evidence.

The accountability and effectiveness of humanitarian actions are not good enough. Humanitarians still do not have a clear understanding of the concept of accountability with leads to the fact that it is often poorly maintained. Professionals are not able to gather enough data to prove their actions and measure positive changes. The effectiveness of humanitarian assistance also suffers. A lack of appropriate evidence means that humanitarians are not able to find out what exactly is required by the affected population. As a result, their actions fail to meet the expectations of the recipients. Moreover, then a lack of the information about the outcomes prevents them from obtaining an opportunity to improve the situation.

Unfortunately, the implementation of the efficient evidence-base is not well-considered yet, and the debate about it is in the initial phase. Still, some attempts to bridge the existing gap are made. In addition to them, it can be strengthened when professionals receive guideline regarding the usage of methodology. Agencies should cooperate and provide required training programs to improve their evidence-base.

References

Akl, E. A., El-Jardali, F., Karroum, L. B., El-Eid, J., Brax, H., Akik, C., & Oliver, S. (2015). Effectiveness of mechanisms and models of coordination between organizations, agencies and bodies providing or financing health services in humanitarian crises: A systematic review. PLoS One, 10(9). Web.

Alexander, J., Darcy, J., & Kiani, M. (2013). The 2013 humanitarian accountability report. Web.

ALNAP. (2012). Core humanitarian competencies framework. Web.

ALNAP. (2015). The state of the humanitarian system. Web.

ALNAP. (2016). The quality and use of evidence in humanitarian action. Web.

Arroyo, D. M. (2014). Blurred lines: accountability and responsibility in post-earthquake Haiti. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 30(2), 110-132. Web.

Basher, R. (2015). Disaster risks research and assessment to promote risk reduction and management. Wtb.

Birnbaum, M., O’Rourke, A., Loretti, A., & Daily, E. (2014). Disaster research/evaluation frameworks. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 29(2), 1-12. Web.

Blanchet, K., & Martin, B. (2011). Many reasons to intervene. French and British approaches to humanitarian action. London, GB: Hurst & Company.

Bradt, D. (2009). Evidence-based decision-making in humanitarian assistance. Web.

CDC. (2010). Logic models. Web.

Chan, J., & Burkle, F. (2013). A framework and methodology for navigating disaster and global health in crisis literature. Web.

Clarke, P. K., & Darcy, J. (2014). Insufficient evidence? The quality and use of evidence in humanitarian action. Web.

Curmi, P. (2013). Evaluation of humanitarian action. Web.

DARA. (2013). Now or never making humanitarian aid more effective. Web.

Featherstone, A. (2013). Improving impact: Do accountability mechanisms deliver results? Web.

International Initiative for Impact Evaluation. (2016). Impact evaluations. Web.

Kulling, P., Birnbaum, M., Murray, V., & Rockenschaub, G. (2010). Guidelines for reports on health crisis and critical health events. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 25: 377-383. Web.

Lam, E., Torres, A., Zoleveke, J., & Ondrusek, R. (2016). Review RCRC movement response to tropical cyclone Winston. Web.

Polastro, R. (2014). Evaluating Humanitarian Action in Real Time: Recent Practices, Challenges, and Innovations. The Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 29(1), 118. Web.

Roddy, S., Strange, J. M., & Taithe, B. (2015). Humanitarian accountability, bureaucracy, and self-regulation: the view from the archive. Disasters, 39(s2), s188-s203. Web.

Scott, R. (2014). Imagining More Effective Humanitarian Aid: A Donor Perspective. OECDiLibrary, 18, 35. Web.

Smith, G., & Flatt, V. (2011). Assessing the disaster recovery planning capacity of the state of North Carolina. Web.

Tan, Y., & Schreeb, J. (2015). Humanitarian assistance and accountability: What are we really talking about? Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 30(3), 264-270. Web.

Wong, D. (2011). Managing mass casualty events is just the application of normal activity on a grander scale for the emergency health services. Or is it? Journal of Emergency Primary Health Care, 9(1), 1-10. Web.