Abstract

Inclusion is an important educational concept that provides equal opportunities for all students to pursue their academic goals. However, disabled students have often been marginalized in most societies. Indeed, countries that have not effectively integrated inclusion concepts in their mainstream educational systems report low levels of educational enrolment for disabled students. Most developed countries, however, have a better record of implementing inclusion. This paper focuses on inclusion in the UK and how Nigeria can learn from the UK’s inclusion model to implement the same. Insights regarding the implementation of inclusion in developing countries are also explored. Comprehensively, this paper proposes that Nigeria needs to identify its unique socio-cultural barriers to inclusive education, provide adequate educational resources, involve all stakeholders, provide the right legislative framework and adopt a community-based approach if it is to truly realize the goals of inclusive education.

Introduction

“Inclusion remains a controversial concept in education because it relates to varying educational and social values, as well as to our sense of individual worth” (Francis 2002, p. 12). The above statement was made by Francis (2002) (an educational researcher) in an attempt to explain the discriminative nature of many educational systems in the world today. This chapter focuses on the concept of inclusion by elaborating how inclusion is conceptualized in Nigeria and the United Kingdom (UK). Two questions will be answered in this study. The first question investigates what factors to consider before setting up an inclusive primary school in Nigeria (that is inclusive of children with difficulties and disabilities) while the second question investigates barriers and challenges to inclusive education in Nigeria. First, emphasis will be given to explain the concept of inclusion in the educational system and later, the challenges pertaining to the comparison of how inclusion is practised within the Nigerian and UK contexts will be analyzed.

Nonetheless, within the context of accommodating the needs of special students, inclusion is normally perceived as a principle to enable students with special needs to get equal opportunity as typical students. The Wisconsin Education Association Council (2012) explains that ideally, special students are supposed to receive the same opportunities as normal students do. Similarly, in an inclusive setup, special students are required to interact freely with students who do not have any special needs. This is the principle that inclusion strives to uphold. The scope of inclusion focuses on including all calibres of students in the mainstream educational system. The following diagram shows this scope

Studies done to investigate the impact of social exclusion among schools have revealed that students who feel socially included tend to develop desirable academic and social skills (Tomlinson 2005). Such studies were done on mentally retarded students. Here, it was observed that when mentally retarded students were left to freely interact with other students, they developed more desirable social and academic traits (Tomlinson 2005). Studies, which have shown the impact of inclusion on typical students, also reveal that typical students tend to develop a high level of sensitivity to the challenges that disabled students face (when they are left to freely interact with the disabled students) (Sebba 1997).

Empathy and compassion are also other traits that were observed to develop among such students, but overall, it was established that such typical students often developed desirable leadership skills that were (in turn) very beneficial to the society (Sebba 1997). Full inclusion and partial inclusion have also been proved to be beneficial for students with learning challenges (Tomlinson 2005). Research studies are done to show the effect of inclusion on reading comprehension showed that students with learning challenges fared better on reading comprehension tasks when they were exposed to an inclusionary culture (Tomlinson 2005). From these studies, it is also explained that inclusion is not only beneficial to disabled students but to typical students and (by extension) all members of the society as well. Overall, it is also established that an inclusionary culture helps students to understand the importance of collaborative learning (and through the process; they develop tolerance and empathy towards special students) (Tomlinson 2005).

The world has not fallen short of understanding the importance of inclusive education systems. The Salamanca Declaration of 1994 is one such example (UNESCO 1994). This declaration provided the right framework for the implementation of inclusive education systems. Through the same declaration, it was reported that inclusion is the most effective way of curbing discriminatory extremes in education (UNESCO 1994). Therefore, through the adoption of inclusionary educational systems, it would be easy to develop welcoming communities and facilitate the realization of an inclusive society that recognizes the principles of ‘education for all’ (UNESCO 1994).

Different countries have had different experiences with the implementation of inclusion. Indeed, different countries across the globe have different frameworks for implementing inclusion within their schools. However, within this diversity, there is an agreement that most societies today are becoming increasingly diverse (UNESCO 1994). Europe for example is home to many cultures, ethnicities and nationalities. America is also another cultural melt point. This diversity has brought different social and economic contrasts in education (CILT 2006, p. 1). For example, the diversity in educational systems within different states across Europe is probably understated. There are many educational contrasts among different European countries than is conceptualized in conventional literature (CILT 2006). For example, countries like Belgium, Spain and the United Kingdom (UK) have more than one distinct educational system and therefore, it is difficult to say that there is a national education system within such regions (CILT 2006, p. 1).

Developing countries also share this dynamic (Obani 2002). This diversity in educational systems provides a background understanding of how inclusion is practised in such countries. Indeed, it is through such educational systems that inclusion finds its foothold (Obani 2002). Different countries hold their educational systems with pride because they perceive such systems to be a symbol of their cultural identities (CILT 2006. Therefore, inclusive educational systems are only implemented as an antecedent of the existing (mainstream) educational systems. Across the European Union (EU), there has been no specific mention of a unified educational system. Concisely, the Rome treaty and the treaty of Maastricht do not show any specific mention to the understanding of a harmonized EU educational system (CILT 2006. In fact, the treaty of Maastricht limits the mention of any supranational involvement in national educational systems (UNESCO 2007). Therefore, from this understanding, the conceptualization of inclusion in European educational systems can only be understood within the context of different countries.

The US has had a remarkable influence in certain western societies such as Canada (regarding the implementation of inclusion). Canada has witnessed a relentless effort to overhaul the education system so that it can be able to improve its contents and relevance to the society (Canadian Department of Education 2012). The push for change has brought with it a new wave of reform on the Canadian system. Other regions of the world have also experienced the same educational influences. The influence of western educational systems is especially prominent in developing countries around the world (Obani 2002). In fact, after the colonial era, most colonies adopted their masters’ educational systems. For example, the Kenyan educational system traces its roots to the British educational system. Similarly, the Nigerian educational system traces some of its fundamental principles to the British educational systems (Obani 2002).

This paper acknowledges the diversity in educational systems within different regions of the world and the contribution they have had on the implementation of inclusive education systems. However, special focus is given to understand the differences in inclusionary practices between the UK and Nigeria. Since Nigeria was a colony of the British, it would be interesting to understand the differences in inclusionary practices between the two countries’ educational systems. However, some common analytical problems complicate the comparison of inclusionary educational systems between the two countries. These challenges mainly stem from the difficulties in comparative education. The most common challenge facing the comparison of the UK and Nigerian educational systems is the influence of globalization (UNESCO 2007). Globalization has increased the interest of scholars and shareholders in understanding the difference in educational systems among different countries.

However, with this interest, there has been mounting criticisms on traditional modes of comparative education (UNESCO 2007). The strongest argument that has been brought by global influences has been the challenge of countries as nation-states. Therefore, within the context of analyzing the UK and Nigerian educational systems, it is difficult to determine the authenticity of different aspects of the two educational systems. Through this analysis, globalization is quickly redefining the global forces influencing the development of educational systems (UNESCO 2007). Therefore, issues, which transcend the national level, are quickly being considered as important components in the analysis of educational systems. Furthermore, the influence of globalization in comparative education is further compounded by the fact that globalization has different effects in many parts of the world (UNESCO 2007). Moreover, studies, which have focused on these differences, have only focused on developed economies and certain parts of developing Asia. Therefore very few works of literature cover inclusion in developing countries (Canadian Department of Education 2012).

Cultural expectations also create an important dynamic to the understanding of different educational systems within the UK and Nigeria. These two countries have very dynamic cultural attributes that make the understanding of educational effectiveness equally distinct (Obani 2002). The importance of these cultural dynamics is understood from the comprehension that inclusion is aimed at developing a sense of contentment within the community that all students are being treated equally and fairly (Obani 2002). However, different societies have different standards of fairness or inclusion. In other words, lower levels of inclusion standards in the UK educational system may be perceived to be satisfactory in Nigeria (Obani 2002). Similarly, a satisfactory level of inclusion in Nigeria’s educational system may be perceived to be inadequate in the UK educational system. Therefore, it is very difficult to compare the inclusion practices between the two countries on an equal level.

This paper recognizes the challenges in understanding the educational systems between Nigeria and the UK but comparatively, the study intends to highlight the factors to consider when setting up an inclusive primary school in Nigeria. Evidence will be borrowed from the inclusion practices in Nigeria and how Nigeria can borrow from inclusionary practices in the UK to set up a primary school. To achieve this objective, this study includes five chapters. Evident in earlier sections of this paper, the first chapter introduces the study and shows the challenges present in the comparative analysis of the Nigerian educational system and the UK educational system (plus other educational systems in other developing countries). These second chapter will conceptualize the methodology for obtaining the findings of this paper. Here, a special focus will be given to comparing how inclusion is practised in Nigeria and how it can be compared with the UK and other developing countries.

In addition, special emphasis will be given to show the concepts of inclusion and integration within the UK and Nigerian educational systems. Literature pertaining to the practice of inclusion in the UK and other countries around the world will also be mentioned but there will be a special focus on the practice of inclusion in Nigeria and the UK. The third chapter of this paper will show the history and gains of inclusion in the UK and the lessons that can be learned when implementing an inclusive educational system. Here, there will be a special mention on policy, provision and practice changes that can be done to the Nigerian educational system, to realize the gains that the UK educational system has realized (in terms of inclusion). The fourth chapter will go on a different tangent and analyze how inclusion is practised in other developing countries to expose different ‘learning’ areas that Nigeria can adopt in its educational system to make it more inclusive. The last chapter of this paper highlights the main findings of this study and the important areas of further research.

Methodology

Research Design

The methodology for this study was based on the qualitative research design. The qualitative research design was used as a precursor to quantitative research design (which may form the basis for future studies on the factors to consider before setting up an inclusive primary school for children with special needs, difficulties and disabilities). The usefulness of the qualitative research design was therefore limited to getting a comprehensive view of the research problem (based on the backdrop of existing literature) (Rachels 1986). The use of the qualitative research design was also supported by the fact that this research methodology is flexible and supports the inclusion of case study research information. As evidenced in subsequent sections of this paper, information from case studies was relied on to outline a framework for the development of the study’s findings.

The inclusion of such data was supported by the qualitative research design. The nature of the research topic was also too complex to be answered by a “yes” or “no” response and therefore the use of the qualitative research design were able to expose the underlying dynamics of the research topic. The simplicity of undertaking the qualitative research design was also a huge attraction for this research because it minimized the cost of undertaking the research. Therefore, research costs associated with travelling, seeking appointments, developing questionnaires (and the likes) was minimized in this regard. This advantage is not only mirrored as a cost advantage but also as a functional advantage. For example, the use of secondary research gives researchers more time to focus on the important parts of the research as opposed to spending a lot of time sourcing for the research information. Instances of burnout and exhaustion were also minimized in this regard. Furthermore, considering this paper focuses on the use of secondary research information as the main form of data collection, the dependence on the population sample was unimportant. Therefore, meaningful research could still be obtained with a small case study or a collection of relevant cases.

Data Collection

After identifying the research topic for this paper – “factors to consider when setting up an inclusive primary school in Nigeria for children with special needs, difficulties and disabilities” the literature sampled in this paper were sourced from keywords pertaining to the same. The works of literature were hereby sourced using a dual-faced strategy where inclusion in Nigeria formed the first part of the strategy and inclusion in the UK formed the second strategy. The keywords used were inclusion, special needs, and inclusive education. Despite the inclusion of these keywords, some papers were excluded from this report because they did not reflect inclusion in the Nigerian or UK contexts. Except for the works of literature focusing on inclusion in some of the developing countries analyzed (Vietnam, South Africa and Tanzania); only those papers that focused on inclusion in the UK and Nigeria were included in this study.

The data collection process was guided by the concept of having a comprehensive understanding of the research problem. From this understanding, this paper used secondary data as the main data collection strategy. Secondary data was collected through the inclusion of published data and was preferably used in this study because of its easy accessibility and relative cheapness. For purposes of this study, the secondary data information collected was useful in identifying the primary areas of deficiencies for implementing inclusion in the Nigerian educational system. Indeed, Rachels (1986) explains that secondary data make primary data more specific by identifying the specific gaps in research and providing crucial guidelines on how to fill these deficiencies.

The main disadvantage associated with secondary research data is its limitation to the objectives and wishes of the researchers who formulated them. From this understanding, it may be difficult to correctly identify the right framework to fit a previously formulated research design to a new and unrelated research framework. This paper also recognizes another disadvantage of the secondary research information which centres on its high probability to contain out-dated information which may not be directly related to the context of the current research. This weakness is especially relevant to this paper because the nature and accuracy of our research outcome rely on the accuracy and ‘up-to-date’ nature of the research sources. More so, the research topic centres on an ongoing issue because the Nigerian and U.K educational systems change often. Therefore, the research sources used need to reflect the current nature of the research topic. Secondary research data may fail to provide the correct research sources in this regard but this paper recognized these weaknesses and incorporated online research sources as a form of published text to supplement the input of books and journals as other sources of secondary research data. However, the emphasis was made to include only credible online research data (such as government publications and the likes). These types of online material contain minimal bias

The quality of the secondary research sourced was guaranteed by the quality of sources obtained (books, journals and credible online sources). Some of the journals obtained were peer-reviewed while all the books used were subjected to a thorough publishing process. Comprehensively, the information contained from books and journals was assumed to be error-free and reliable. Moreover, Rachels (1986) affirms that peer-review journals contain dynamic pieces of information and unbiased data which may be developed by including pre-conceived ideas in the research process. This justification informs the high reliance on books and journals as the main sources of secondary data.

Data Analysis

As explained in earlier sections of this paper, the main types of literature used were journals, books and websites. The main differences among these types of literature were their forms because the journals and books were in print form while the website contents were in virtual form. Their credibility is however expounded in subsequent sections of this paper. During the data analysis process, different themes were highlighted. The most common themes present in this paper were the importance of cultural support in inclusion, stakeholder involvement, proper utilization and allocation of resources, community participation and the importance of legal structural support. These themes guided the data analysis process and ultimately, formed part of the recommendations of this study.

Besides the themes mentioned above, this paper also focused on two other themes. The first theme was ‘equality’ and the second theme was ‘inclusivity’. The theme of Equality is perceived as a mainstream theme in this paper because of the unequal treatment between special students and typical students. Inclusivity is also perceived to be another mainstream theme because it pertains to the educational system and how equality can be practised within the Nigerian educational system. These themes are central to the understanding of this paper.

The data analysis process was mainly centred on providing a critical analysis of the research findings. The importance of undertaking this critical analysis was to improve the understandability of the findings and eliminate any unnecessary information from the huge volumes of literature obtained. Lastly, the critical analysis method improved the clarity of the findings obtained. This data analysis method mainly incorporated five steps. The first step included identifying the problem (elementary clarification) so that different elements of the problem could be analyzed and any linkages observed. The second step involved an in-depth clarification of the problem to identify the values, beliefs and assumptions underlying the problem. The third step is the inference stage where ideas and insights regarding self and group learning were identified to link ideas with propositions. The fourth stage involved the analysis of ideas and the relevant propositions within the social context (essentially, excellent judgment skills were important in this stage). The last stage was the strategy formation stage. This stage involved the identification of unique actions that eventually provided a solution to the research problem.

Additionally, the member-check technique was used to check the validity of the research information obtained because it also evaluated the accuracy, credibility and transferability of the research information obtained. The member check technique works by submitting the research findings to the sources or sample sources (Rachels 1986). In this study, the research information was compared to the existing pool of research sources and any distinctions checked to report on the accuracy or validity of the findings. Highly accurate and valid research information reflected the views, feelings and experiences of the authors who developed the previous research (Rachels 1986).

Literature Review

As mentioned in earlier sections of this paper, inclusion is practised differently around the globe. Like other developing countries around the world, Nigeria still lags in the implementation of inclusive education (Ikoya 2008). Garuba (2003) observes that Nigeria’s journey towards realizing an inclusive educational system is explained by two eras. The first era was defined by the pre/post-colonial period (between the fifties and seventies) where there was a lot of missionary work in the West African country and the second era was characterized by the growth in service provision. From the understanding of policy development, it can be seen that Nigeria has made tremendous strides in providing inclusive education to disabled students. However, the implementation of comprehensive inclusive education has been a daunting task for Africa’s most populous state. Corruption and mismanagement are only some of the challenges that characterize the implementation of inclusivity in the country’s educational system (Sofo 2011).

Some of the challenges described above have led to poor enrollment and the exclusion of some disabled students in Nigeria’s education system. Moreover, Horwitz and Jain (2011) explain that equality and fairness in African education systems are extremely low. Albeit there may be some decisive actions taken towards improving equality within Nigeria’s educational systems, there seem to be no concrete efforts made to cement these gains. In fact, Obani (2002) argues that even at the policy level there are still very weak structures that support inclusive education in Nigeria. For example, he explains that integration is the main criterion used to address the needs of special students. Comparatively, only a few international organizations have bothered to address the inequalities in the education system (Emerald Group Publishing 2011). For example, at the 12th Annual Conference of the National Council for Exceptional Students, few professionals gathered to address some of the fundamental challenges hindering the realization of an inclusive education system in Nigeria (Obani 2002). At the conference, it was agreed that the old system of education was too rigid to effectively address the needs of special students.

Another problem associated with the challenges of implementing inclusion in Nigeria is the negative attitudes associated with disability. For example, Garuba (2001) narrates an example where some parents in Nigeria threatened to withdraw their children from a school that admitted a student with epilepsy. From this example alone, it is crucial to highlight that the prevailing culture within the country has a strong role to play in the perception of special students and the entire notion of disability in the country. For example, it is not uncommon for parents in Africa to deny their children educational opportunities because they are an embarrassment to their families (Ngunjiri 2010). This problem is therefore not only exclusive to Nigeria. Furthermore, there is very little awareness regarding the existence of special education or even the fact that disabled students can still go to school and make a living from it.

Comparatively, Kenya shares some of the main challenges Nigeria faces concerning the implementation of inclusion (Ngunjiri 2010). For example, according to a UN report, cultural barriers and religious inclinations are some of the main deterrents for the full realization of inclusion in Kenya (UNESCO 2007). Beyond the cultural inhibitions of embracing special education in Nigeria, there is more focus on reducing illiteracy at a national level (thereby overshadowing the importance of adopting special education) (Jonsen 2010). International education organizations are assumed to be part of the problem because they have failed to give inclusion enough attention (as opposed to reducing illiteracy) (Landorf and Nevin 2007). The Nigerian government has also followed this trend and consequently emphasized basic education at the expense of special education. This emphasis has been seen through the implementation of the Universal Basic Education program. The program mainly emphasizes on primary-level education and formal education. Whenever specialized education is mentioned, there is usually an inclination to refer to nomadic communities in Nigeria and the girl-child (Seguin 2011). Therefore, children with special needs are rarely given national attention.

The reality facing most proponents for special education in Nigeria is that special education is constantly fighting with other educational needs such as the reduction of illiteracy. Therefore, the biggest question stands to be what can be done to implement inclusion in such an environment? Given the hostile nature towards disability and special education in Nigeria, there is a strong need to adopt a cautionary approach when implementing inclusion. The scepticism of fully implementing inclusion in Nigeria is not only expressed in the West African country but also in the US (Merchant and Ärlestig 2012). Therefore, it is common to see many researchers express extreme pessimism regarding the practicality of implementing inclusion (fully) in the Nigerian context.

Comparatively, the UK has had a significant degree of success in the implementation of inclusionary principles in its educational system. Like Nigeria, the UK was among the first countries to ratify the Salamanca statement of 1994. In addition, in 1991, the UK ratified the UN convention on children’s’ rights and two years later, the country assumed responsibility for implementing the 1993 Standard rules of education (Arnot 2005). Different countries have expressed different levels of concern towards the implementation of inclusion in their education systems. However, the UK’s response has not been entirely positive because Arnot (2005) observes that even though the progress towards full inclusion has been forthcoming, the process has been painfully slow.

When analyzing inclusion in the UK educational system, it is important to understand the educational dynamics within the four countries that constitute the UK. The Department for Education and Skills (2004) explains that some common inclusionary practices (within the four UK countries) make it easy to understand inclusion in the UK. However, there are also some other interesting dynamics within the four countries which make the implementation of inclusion different within the four countries. Similarly, there is no central and integrated policy within the UK that governs inclusion within the four countries, each country has its own policy statement (HMIe 2007).

Within the UK educational system, inclusion has mainly been studied under the assumption that there exist four major special groups – students from ethnic minorities, gipsies and travellers, looked after children, and students who hail from minority language groups (Condie 2009). Throughout the UK, there is a general understanding that the educational needs of minority and disadvantaged groups are addressed within the country’s educational systems. As mentioned in earlier sections of this paper, the detail and educational focus of these provisions vary within the countries but the principle of provision integration remains very central throughout the UK. However, there are instances where specialized education is needed. Such schools only admit students with severe disabilities or extreme behavioural conduct, which prevents them from being integrated into the ‘normal’ classroom set up (Condie 2009).

Government publications normally refer to disabled and minority groups as part of the student body. Through these publications, the government gives guidance to how inclusion should be practised and in certain cases, offers funding for its implementation. Guidance and funding are probably the only responsibilities that the national government does before it leaves all other aspects of policy and strategy formulation to the local education bodies. Therefore, the introduction of new policies and legislation governing education has mainly been done at the local or regional levels. These policies are mainly tailored to meet the local needs (but within the national education policy). Because of this reason, many of the examples of inclusion within the UK are mainly explained in small-scale contexts (Strand 2007). Similarly, it is often difficult to evaluate systematically such cases or examples of inclusion in the UK (Francis 2002). This is the main challenge observed by many researchers studying inclusion in the UK because they see much of UK literature on inclusion to be largely descriptive without any strong conclusion regarding the effectiveness of inclusion within the country. However, bearing the policy differences of inclusion (within the four countries constituting the UK), it is crucial to analyze the inclusion context within the four countries.

Even though the UK has made tremendous strides in improving inclusion within its educational systems, Derrington (2007) observes that many children in the country are still missing quality education. This statement was made in reference to the educational system in England, which excludes about 9,000 students while about 10,000 students miss getting an education (Condie 2009). These statistics arise from the complexity observed in registering for a school and the complexities in dispersion. Most of the students, who fail to get a good quality education in England, are asylum seekers and refugees. Candappa (2000) indicates that in situations where the rights of the children are consistently being violated, it is important to include the participation of the children in such matters. However because England does not recognize children as legal entities, parents are required to make decisions on behalf of their children.

At a policy level, local authorities are required to provide full-time education for all children. This policy provision applies to all students who live within the jurisdiction of local authorities (Corbett 2001, p. 5). Therefore, even if a child is new to England, he or she has the same rights as a child who has been born in England. Similarly, nationality and immigration status do not have a bearing on the evocation of this right. Similarly, all schools in England are bound by the racial relations Act (2000) to provide equal educational opportunities for students of all races (Lloyd 2002). This act is among many other legal provisions that guarantee the concept of inclusion in England’s education system.

In Scotland, it is a law for all students to access education (regardless of any socially excluding factor) (Candappa 2007). Only in special circumstances can this right be disrespected. The Scotland Act of 1995 ensures that all local authorities should highlight the physical circumstances of the students so that they are assisted to blend with other students. Usually, special students such as deaf, blind or students with mental problems) are given extra support in learning (Ashard 2005).

Inclusionary practices in Wales are said to be very similar to those of England. For example, no student is above the other because all students are treated the same. However, depending on individual cases, additional support may be accorded to students who have special needs. As the similarities between inclusionary practices in England and Wales, Northern Island’s inclusionary practices are also closely similar to the two countries. Like other countries in the UK, special students in North Ireland also have the same rights as every other student in the country (Jackson 2005, p. 2). However, local authorities often practice a holistic approach to inclusion by providing guidance to parents who have children with special needs. Here, the advice is given regarding the best ways that such students can be helped and effectively integrated with other students (Mac Poilin 2004).

Across the four countries in the UK, there is a lot of similarity in inclusion practices (CILT 2006). However, there seems to be a sharper difference in inclusion policies between Scotland and England. Similarly, since there are many similarities between inclusion practices in England and Wales, there is a strong difference between the inclusion practices in Scotland and Wales (Connelly 2003). However, even while making this observation, it is crucial to highlight that the four countries of the UK have distinct cultural and linguistic differences. For example, in Scotland (where all children are treated the same), foreign students have to learn the Scottish accent while interacting with other students out of the classroom. In addition, across the four countries of the UK, there is a sharp focus on the unique strengths and weaknesses of every student (ContinYou 2005). Therefore, policies are designed to address these unique dynamics.

From the educational practices of Nigeria and the UK, we can see a close interplay between the concepts of inclusion and integration within the two countries. Integration has often deemed a precursor to inclusion but inclusion is more than integration because its goals transcend the goals of integration. Disability Council of NSW (1998) explains that

“Integration increases the opportunities for the participation of a child who has a disability within the educational system of a mainstream school while Inclusion is the full participation of a child who has a disability within the educational system of a mainstream school” (p. 1).

Therefore, within the Nigerian and UK educational contexts, integration seems to be the main step taken by the Nigerian government to address the needs of disabled students while the UK seems to be a step away from full inclusion. Nigeria is also still experiencing socio-cultural factors that inhibit the full implementation of inclusion within the country’s educational systems (Obani 2002). Some of these challenges have been identified in earlier sections of this study and they include corruption, mismanagement and poor attitudes towards the inclusion of special needs in mainstream education. The UK does not share some of these disadvantages and if it does, it is in relatively smaller proportions. For example, in Scotland, students are required to learn the Scottish dialect while socializing out of the classroom (Learning Teaching Scotland (LTS) 2003). This provision may be perceived to be an exclusionary basis for special students.

Nonetheless, there is a clear difference in commitment between the Nigerian and UK educational officials when enforcing inclusion. There is a stronger commitment within the UK government to enforce inclusion within the country’s educational system but Nigeria does not share this conviction (Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) 2008). In fact, as observed in the earlier assertions of this paper, most of Nigeria’s commitment towards enforcing inclusion is done on paper. There is no clear framework for the follow-up to see whether inclusion is really observed within the country’s educational systems. Comparatively, in the UK, the government has tasked the local authorities to see that inclusion is practised within their jurisdictions. In fact, this paper shows that within all the four countries of the UK, all students are treated the same regardless of their physical disabilities, status, race or mental status. The government also provides special assistance in cases where students are severely disabled (Garuba 2003). This level of commitment is not seen in the Nigerian context.

The extent of inclusion within the Nigerian educational system is also only witnessed within certain states and geographical regions. For example, it is explained that urban areas have a better record of addressing the needs of special students. Students in rural areas do not have access to education and more importantly, students with special needs get to be discriminated because of the lack of availability of schools in remote locations.

Inclusion in the UK is done on a national context. All countries within the UK practice inclusion at very high levels (Condie 2009). In fact, every regional government is left to implement inclusion within its jurisdictions. Comparatively, the implementation of inclusion in Nigeria takes a state approach. Some states are required by law to implement inclusion while others are exempted from such provisions. For example, we can see that the ‘Plateau State Handicapped law’ only applied to the Plateau state and not all states within Nigeria. Such selective administration of inclusion is not witnessed within the UK context.

The implementation of inclusion in the UK is also mainly undertaken by the local or regional governments, which source financial and administrative support from the national government. However, in Nigeria, the push to implement inclusion is mainly a privy of the national government with very little input from the regional governments. This administration structure is partly the reason for the poor implementation and follow-up of inclusion at the regional level. The UK structure of administration is, therefore, more effective because it allocates responsibility to not only regional governments but the local administration as well. Through this strategy, there is a stronger grass root support for inclusion. In Nigeria, the push for inclusion is only witnessed at the national level and within professional organizations. Therefore, the grass-root perception of inclusion is very abstract and barely scratches the surface of what inclusion really entails. From these dynamics, there are many differences surrounding the implementation of inclusion in Nigeria and the UK.

History and Contemporary United Kingdom

“Some children should not be included in the mainstream education system because they could create an uncomfortable environment” (Nutbrown 2005, p. 7). Such is the nature of statements that triggered off an unending debate about whether to practice inclusion in the UK or not. Indeed, such exclusionary statements were common in earlier decades not only in the UK but in other developed countries as well (UNESCO 1998). Today, such statements would be heavily condemned as harsh, antagonistic and even preposterous (Landorf and Nevin 2007). However, the number of people who had negative attitudes towards inclusion in the UK was many. Nonetheless, within the four constituent countries of the UK, there were some apparent differences in opinion and policies concerning inclusion (because there were different socio-cultural influences within these territories). However, influences from mainstream Europe defined the different attitudes held by all the four countries of the UK (regarding inclusion).

This chapter seeks to complement the apparent differences in inclusive practices within the four territories of the UK through a strong reference to the historical practices of inclusion in the UK. The main aim of understanding the historical practices of inclusion in the UK is to provide a basis for understanding how inclusion can be improved in Nigeria and how inclusion practices in the UK that can also be implemented in the Western African country. Comprehensively, this chapter seeks to establish a model (for the practice of inclusion in the UK) which can effectively be adopted by Nigeria so that it can also accomplish the same goals that the UK has achieved. This chapter will also suggest how the provision, policy and practice in Nigeria should look like so that it can get to where the UK is today. To do this, an analysis of U.K’s journey towards inclusive education will be analyzed in four phases (before the 50s, 1950s to 1960s, 1970s to 1990s and the 2000s).

Journey Towards Inclusion in the UK

Before the 50s

Based on the past poor human rights record of the UK and its influence on the educational sector, Kisanji (1999) points out that there is nothing to celebrate about UK’s earlier practices on inclusive education (he makes this statement with an implicit reference to inclusion practices throughout Europe as well). In the past, the common perception about disabled people in the UK was that they were a social threat and a contaminant of the otherwise ‘pure’ human species of the country (Kisanji 1999). Referring to the poor human rights record in the UK, it is important to observe that people with disabilities were either killed or used as a form of entertainment for the otherwise ‘normal’ population.

The common argument for condoning such atrocious acts was that the society had to be protected from being contaminated by disabled people. However, there was also a counter-argument stipulating that disabled people also had to be protected from society (UNESCO 1994). From the growing divisive sentiments, there emerged a philanthropic group that advocated for the introduction of custodial care for people with disabilities throughout the country (Kisanji 1999). Soon after this movement gained popularity, asylums were established throughout the UK, where disabled people were confined and given food and clothing. The common misconception made by researchers studying the history of education inclusion is the portrayal that these asylums were the first forms of educational institutions. However, Bender (1970) explains that these asylums were not meant to be educational institutions. On the contrary, people with severe disabilities (like mental disabilities and intellectual impairment) were confined in healthcare institutions so that they would be given custodial care or treatment (whichever suited their conditions). Nonetheless, throughout the UK, all disabled people were experiencing a period of institutionalization (Coleridge 1993).

Towards the onset of the 15th century, some special schools started to emerge in some parts of the UK. Majority of the students in these special schools were suffering from sensory impairments. For a considerable period, ‘other’ special student groups were ignored until the expansion of the public schooling system. The early special schools to be established in the UK mainly focused on providing disabled students with vocational skills. Naturally, from the focus on vocational skills, the curriculum used in special schools was different from that offered in public schools. In addition, since the move to care for disabled people was largely championed by philanthropic organizations, the first special schools were owned by these philanthropic organizations (Kisanji 1999). The influence of the government was felt much later.

The 1950s to 1960s

It was only at the start of the 1950s period that people (educationists) started to question the ‘group’ approach used to educate all students with special needs. From this argument, different disability groups were established (Wolfensberger 1972). During the 1950s period, there came a growing sense of contempt regarding institutionalization because it was perceived to be retrogressive towards realizing an all-inclusive educational paradigm (Kisanji 1999). However, even though there was a growing level of contempt for institutionalization, the idea of transferring people from institutions and integrating them into the community setting was marred with many hurdles.

Despite the existence of these hurdles, there was a common agreement (among educationists) that the concept of institutionalization had to be eliminated and normalization introduced. This process has been ongoing and even today, we can still see how difficult reintegrating people with disabilities back into the society is (for example, integrating people with mental disabilities back into the society) (Barton 1995, p. 156). Even though normalization was a step forward from the concept of inclusion, it bore some inherent weaknesses. For example, normalization did not factor societal differences or the diversity in education (vocational or otherwise) and the existing opportunities that existed for adults at the time (Kisanji 1999). Therefore, from the weaknesses posed by normalization, it became important to examine what is considered important and the individual uniqueness that every student had.

Despite the criticisms levels against normalization, there was still a strong argument among scholars in the UK who supported integration and the placement of disabled students in special schools (Kisanji 1999). Implicitly, the placement of disabled children in special schools started the move towards special education. However, the introduction of special education brought other challenges to the adoption of inclusive education. Among the problems brought by the introduction of the inclusive education system is that disabled students possessed a problem that made them ineligible to learn through the conventional educational curriculum (Kisanji 1999). The introduction of the special education system was also criticized for legalizing segregation and racial prejudice because it used an unfair method of identification and assessment (Ainscow, 1991). For example, in the UK (and other parts of Europe and North America), special schools bore large populations of students from minority groups such as Africans, Hispanics and Latino-American groups. Therefore, the concept of special education systems was criticized for perpetuating racial segregation (Wang et al. 1990).

There was also another problem in the administration of learning duties because special schools introduced specialists in special education and therefore, regular classroom teachers passed on their duties to these experts because they believed special students could not fit into their skillset (Kisanji 1999). Another criticism levelled against special education was its capacity to allow for the allocation of educational resources to special schools while such resources could have been easily channelled to mainstream educational systems and support more flexibility and responsiveness in the national educational system (Ainscow 1991). Finally, Kisanji (1999) observes that the introduction of the special education system lowered the expectations of teachers towards special students and therefore, the teachers easily condoned mediocre academic performance from special students. Furthermore, the methodologies employed to assess tasks and associated behavioural teaching strategies heralded the introduction of disjointed and uncoordinated skill execution, thereby reducing the meaning of learning to all the students concerned.

From the apparent weaknesses of special education systems, integration was perceived to be a more progressive educational paradigm for the UK. Indeed, integration acknowledged the existence of a continuum of services that cut across special and regular schooling systems (Kisanji 1999). The support of integration was further complemented by a UN declaration supporting integration as a continuum of provision. The support of the UN was considered tremendous progress towards inclusive education because the international body does not provide ‘out-of-context’ leadership because its policy proposals are born from professional thinking, research and practice.

It is reported that most of the policy improvements that support inclusive education in the UK and the US were largely spearheaded by UN recommendations on the same.

Through the support of the UN and its specialized agencies, the endorsement of inclusive education by professional and political groups has been forthcoming. Even though certain restrictive terms like ‘special education needs’ and ‘least restrictive environments’ were abolished by the UN and its subsidiary agents, there was a lot of confusion regarding the implementation of these practices at the national or local levels (Bray, Clarke and Stephens 1986).

Throughout the UK, there was widespread concern that existing legislation did not go far enough to include all aspects of inclusion in the regular schooling system. This concern was however not only reported in the UK; certain European countries like New Zealand and other western countries like Australia and the US also harboured such concerns (Kisanji 1999). In the US, professional advocacy groups launched the Regular educational Initiative (R.E.I) to support recommendations for merging special education into mainstream educational systems. The inclusion of special education into mainstream education was to include all resources in the special educational system (like teaching staff and learners) (Kisanji 1999). Some of the countries identified above (like New Zealand and Australia) supported this quest but left the choice to include special students in mainstream schooling systems to the parents (Kisanji 1999, p. 3).

In the UK, the integration of special students into the mainstream schooling system was introduced through the code of practice. The Local Education Authority (LEA) was mandated to enforce this policy provision (Kisanji 1999). The code of practice ensured that all students in the national education system were provided with the resources to learn (regardless of whether they were disabled or not). However, concerns were expressed regarding the increased emphasis on parental choice because it undermined the principles of inclusion (because giving parents the choice to determine the educational fate of their children promoted exclusion) (Kisanji 1999).

Under the 1944 education act, children who had disabilities were categorized as such because of their classification of disability status through medical terms. The common perception of such students was that they could not be educated. In fact, some of these students were considered to be mal-adjusted while others were considered to be educationally abnormal (Kisanji 1999). Since these students were considered abnormal, the introduction of special schools was considered justifiable.

The 1970s to 1990s

The change in the perception of special schools was heralded by the introduction of the Warnock report in 1978 (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006). This report rapidly changed the conceptualization of special education needs because it introduced a new term of ‘integration’ (which later evolved into the concept of inclusion). The shift in perceptual paradigm was informed by the realization that all students had the same goals (enjoyment, independence and understanding). All subsequent education acts based their legitimacy on the Warnock report because they demonstrated progress in attitude shift regarding special education. In fact, subsequent educational acts tried to include all children in a common educational framework where there were no distinctions between special and ‘typical’ students (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006). This shift in ideology has been largely representative of the international move towards inclusive education.

The introduction of the Warnock report was a historical step towards moving the UK educational system to be more inclusive although there was little effort given to allocating enough resources to support the different recommendations proposed in the report. For example, there were insufficient financial resources allocated towards extra training of staff (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006). This shortfall was experienced despite the consistent closure of several special schools throughout the country.

The introduction of the 1988 education act provided a leeway to harmonize the national educational curriculum because it established a system of league tables where schools competed against one another based on their academic success (Ainscow 1994). Nonetheless, the Warnock framework was largely in effect because there was a consistent reduction in the population of students in special schools while there was a subsequent surge in the number of special students in mainstream education systems. Comparatively, the number of students in special schools was high in the 80s but throughout the 90s, this number flattened out.

Different local and national legislations complemented international support for inclusive education. For example, in the UK, the 1997 Green Paper Excellence for All Children Meeting Special Educational Needs was introduced by the Labour government to support the UN recommendation for governments to adopt inclusive educational systems (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006). This legislation was also introduced as an approval to expand the public education system to address the needs of special students as well. This progress marked a major milestone in the shift towards inclusive education for the UK educational system. Thus, the UK government positioned itself to be a world leader in the provision of inclusive education (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006).

The 2000s

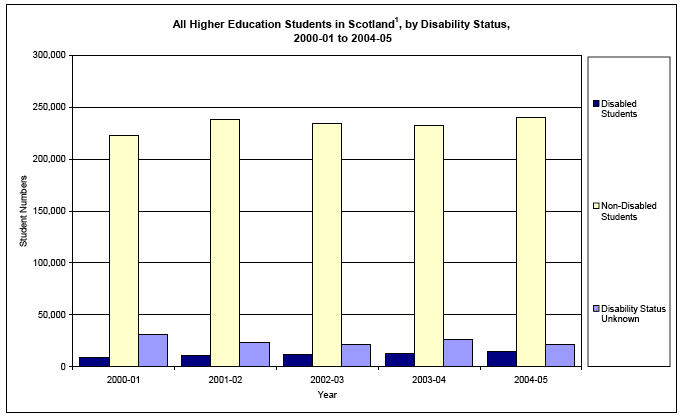

It is important to acknowledge the contribution of the 1978 Warnock report in revolutionizing the UK education system throughout the 2000s. Indeed, through the report, the number of students with special needs who are educated in special schools is less than 1% (of the student population with special needs) (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006). The proportion of students with special education needs in the national education system has also increased to 18% and the percentage of students with statements of special educational needs has hit a plateau over the years at 3%. The following graph shows the ‘plateau’ enrolment of disabled students in Scotland

The increased enrolment of special students in the UK mainstream educational system has been attributed to the Warnock report (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006). The UK government adopted the special education needs a framework and sought to improve it through the introduction of the Special Education Needs and Disability Act (SENDA) of 2001 (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006). The 2004 Special education needs strategy Removing Barriers to Achievement act also improved special education needs in the UK. For example, through this act, the government has substantially increased the level of investments in inclusive education. In the same regard, the government has almost doubled the level of investments in inclusive education from (2.8 billion Euros to 4.1 billion Euros) (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006). Nonetheless, Derrington (2007) explains that the different acts of education introduced in the recent past have struggled to keep up with the divergent needs of over 1.5 million students categorized as special students in the UK educational system.

However, the National Autistic Society of the UK acknowledges that there is more awareness now about the inherent differences in special education needs among special students (compared to the introduction of the Warnock report in 1978).

While the Warnock framework is largely credited with transforming the UK educational system to be more inclusive, its failure to cope with today’s educational challenges is a major concern for all educational stakeholders. For example, its failure to address the rising number of children with autism and emotional or behavioural difficulties is increasing more doubt about its ability to stay relevant in the future (Farrell 2001). Some of these weaknesses have increased condemnation about the government’s program of inclusion and more importantly, its role in closing down special schools. In its defence, the government has often said that it had no policy for closing all special schools (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006). Comprehensively, the government’s response to these issues has been largely uncoordinated and confused.

However, there are several similarities between the objectives of most government proposals and policies like the 2004 Special education needs which have been largely built around addressing the needs of special students in the educational context (House of Commons (Education and Skills Committee) 2006). These objectives have also been built around the prospects of improving the standard of education for special students and equipping the workforce for all staff catering to the needs of special students. These objectives are also shared by the Warnock report of 1978.

Nonetheless, Farrell (2001) observes that the objectives of the 1978 Warnock report were difficult to achieve (despite the introduction of the 1981 legislation) while other policy recommendations like the 2004 Special Education Needs strategy also failed to provide a clear roadmap to how the needs of special students would be effectively realized. Derrington (2007) observes that it may still be difficult to realize the true objectives of the 2004 special education needs act because there has not been a real policy shift in the current administration regarding the prioritization of special student needs. Because of the apparent shortcomings of existing legislation regarding inclusion in the UK, there are many calls now to review the concept of inclusion and special education needs in the country (Derrington 2007).

Nonetheless, through the progress of the UK educational system in embracing inclusion, there are tremendous milestones that have been made to address the needs of special students. Most of these milestones have not been covered by other countries around the world and most importantly they have not been realized by Nigeria. Therefore, through the experiences of the UK, Nigeria can learn from the UK’s model to adopt inclusion effectively.

How Nigeria can use the UK as a model to realize the Goals of Inclusion

As can be seen from the UK’s journey to include inclusion in its mainstream educational system, the process is fairly difficult and bumpy. Indeed, from the few references made to other western countries, the journey to adopt full inclusion requires constant participation and negotiations. Even though the goals of inclusion have not been completely realized in the UK, the European country can easily provide a framework for its counterparts in other parts of the world.

Nigeria can truly learn from the lessons which have already been documented in the UK but most importantly, it can effectively learn from the ‘unmentioned’ lessons that have been characteristic of the fight for inclusive education in the UK. One major lesson that can be learned from the UK is that the journey towards inclusive education takes a very long time. In other words, the journey to truly embracing inclusion is a process rather than an event (Ainscow 1995). This process is characterized by constant negotiations which portray back-and-forth progress towards embracing inclusive education.

As can be evidenced in earlier sections of this paper, the quest for inclusive education started as early as the 15th century and till now, full inclusion has not been completely realized (even though historical milestones have been registered in the same regard).

Nigeria’s quest to adopt full inclusion should therefore not be perceived as an event but rather as a process. Patience is an important virtue in this regard because the full benefits of inclusion are only realized slowly (Thomas 2005).

Another lesson that the UK offers is centred on the fact that the government cannot fully implement inclusion by itself. In other words, other educational stakeholders (like the private sector) also need to be on board when implementing full inclusion. Through the history of inclusion in the UK, we saw that private organizations and other charitable organizations were the first entities to address the needs of disabled people. Indeed, the first special schools in the UK were fully owned by such organizations. In addition, when disabled people were rebuked for their stature in the society and some of them even killed because of their status, the charitable organizations offered refuge to this minority group and provided them with their basic needs. It is through this initiative that the first special schools were adopted because the initiative heralded a period of institutionalization (which later turned into special schools and finally, the concept of integration was birthed). Government support only came later.

Therefore, it is wrong to expect the Nigerian government to fully implement the concept of inclusion by itself. Other educational stakeholders need to be invited to join in the journey for embracing inclusive education. However, even though the contribution of private stakeholders is important, it is equally vital to provide a good environment where other stakeholders can participate in the realization of the goals and aims of inclusive education. Here, the government should provide the necessary incentives to entice private stakeholders and institutions to invest in the needs of special students. Such an environment will be a catalyst to the quick adoption of inclusive education in Nigeria (Dyson 2001).

Even though it is important to support the inclusion of the private sector in the quest to adopt inclusive education, it is still important to include the contribution of the government in the same cause (Booth 2005). Most importantly, the contribution of the government is centred on providing the right policy framework for the implementation of inclusion. UK’s journey towards adopting inclusion manifests the importance of a tight policy framework because its entrenchment of inclusion has been firmly supported by a strong policy framework. The Warnock report of 1978 provided the right foundation for subsequent legislative acts which entrenched inclusion (further) into the national education system. The introduction of firm legislative acts therefore made it easy to implement inclusion in the national context and provided a legal basis for doing so as well (DfID 2000).

From the UK’s journey towards adopting inclusive education, we can see that Nigeria has to provide the right structures for inclusion if it is to accurately implement inclusion as part of its mainstream education policy. Apart from the virtues of patience and negotiations, it is important to point out that Nigeria should provide the right policy framework for inclusion and accommodate the contribution of not only the government but other private educational entities in implementing inclusion. This comprehensive approach will provide the right environment for the complete implementation of inclusion. However, there are some lessons that the UK cannot provide Nigeria in its journey towards implementing inclusive education because of the contextual, political and social challenges that the two countries face. Based on this understanding, it is important to investigate how inclusion has been adopted in other developing countries because Nigeria shares closer socio-political dynamics to developing countries.

Inclusion in Other Developing Countries

With the increase in the world’s population, the number of disabled people is expected to rise. Currently, about 10% of the world’s population is considered to be disabled. This population group is estimated to be about 750 million people (Polat 1999). Unfortunately, most of the disabled people live in developing countries. World Bank (2009) estimates this figure to be about 80% of the total number of disabled people. Sadly, the number of disabled people living in developing nations have no access to basic services and more importantly, educational services. Recent statistics show that only about 3% of the total number of disabled students in low-income countries goes to school (World Bank, 2009).

The situation varies in the developing world. In Africa, it is estimated that less than 10% of disabled students go to school (UNESCO 2006). World Bank (2003) adds that only about 5% of the disabled students in Africa have access to educational services (limited or otherwise) and only less than 2% of this population group actually go to school. A recent report by Peters (2008) shows that equity in education is a rarely practised concept in developing countries and only about 1% to 2% enjoy equity. These statistics raise important questions regarding inclusion in developing countries. Indeed, different developing countries have had different experiences regarding inclusion and similarly, different countries have made different milestones in the same. It is therefore important to analyze these countries individually.

Tanzania

When we analyze the journey towards inclusion in Tanzania, we can establish that very little progress has been made concerning inclusion. According to the Human Development Index, Tanzania is among the world’s poorest countries. The 2007 UNDP rankings show that Tanzania was ranked 164 out of 177 poorest nations in the world (UNESCO 2009). The link between poverty, disability and educational access is rarely addressed but it is important to point out that about a third of all Tanzanians live below the poverty line (live on less than one US dollar a day) (GoURT 2009).

Many disabled students in Tanzania have found themselves living in a cycle of poverty because of the relationship between poverty and disability. Inherently poverty limits one’s chances of making a decent income and therefore it forces them into begging and seeking handouts. These economic inhibitions have significantly limited the chances of disabled students getting basic access to education. As such, inclusive education has been greatly advanced as a remedy for this problem in Tanzania (Tanzania United Republic 1999). Inclusive education has been recognized by all aspects of educational governance including at the policy level. For example, in 2001, the Tanzanian government established the primary Education development program (PEDP) which strived to provide equal educational opportunities for all students, regardless of their disabilities (UNESCO 2009). GoURT (2009) explains that this educational program strived to “ensure, among other factors, adequate provision of quality teachers, a conducive environment for stakeholders willing to participate in providing education and vocational skills, efficient management in education delivery, and a conducive learning/teaching environment for students and teachers at all levels” (p. 5).

In the first implementation phase of the PEDP program, the enrolment of disabled students into mainstream education was expanded. UNESCO (2009) affirms that the number of disabled students who missed out on education significantly decreased by over three million to leave a paltry 150,000 students out of the mainstream school system. This was tremendous progress. It was estimated that by 2010, the Tanzanian government would achieve a 20% enrolment rate (from 0.1%) of disabled students (GoURT 2009). However, certain disability rights activists such as Rutachwamagyo (2006) poked holes into the government’s plan by stating that there was little reference to the number of eligible and disabled students in the government’s plan. He also portrays a hypothetical situation where he explains that about 99% of disabled students in Tanzania are denied basic education because of poor government policies, negative attitudes of the society towards disability, poverty and other socio-economic parameters including poor communication (Rutachwamagyo 2006).

GoURT (2009) proposes that supporting the concept of inclusion without paying close attention to matters of quality beats the purpose of supporting inclusion in the first place. Referring to the challenges of implementing inclusion in developing countries, GoURT (2009) points out that even though there is substantial progress being made towards implementing inclusion; exclusion is still being practised unabated. For example, in the Tanzanian context, GoURT (2009) explains that “the placement options available for the majority of students with varying difficulties within the Tanzanian education system are limited to special schools and integrated units; a system that continues to exclude the pupils with Special education Needs” (p. 3). Moreover, even though there has been substantial progress in implementing inclusion in Tanzania, Mmbaga (2002) fears that the process is still derailed by traditional educational challenges such as poor resourcing, low teacher morale, shortage of classrooms, poor parental support and high dropout rates throughout the country’s major educational institutions. The challenges and progress of adopting inclusive education in Tanzania largely reflect the challenges for most African countries in adopting inclusion.

Vietnam

Vietnam’s journey to adopt inclusion does not show very divergent challenges for adopting inclusion. Similarly, the journey pursued by the Asian country portrays similar lessons that have been shared in the UK’s journey to adopt inclusion. Vietnam Education Team (2007) points out that Vietnam implements inclusive education by implementing four key pillars for sustaining inclusive education. These four pillars are the involvement of stakeholders, training educators, material development, and family or community participation (Vietnam Education Team 2007).

When we critically analyze how Vietnam includes the participation of educational stakeholders in the adoption of inclusive education, we see that the Vietnamese government collaborates with the national and local education policymakers to provide the right environment for the adoption of inclusive education. Observers point out that these collaborations have been largely successful (Vietnam Education Team 2007).

The second pillar that Vietnam uses in implementing inclusion is training educators. Indeed, training educators shows the contribution of the private sector in implementing inclusion because most of the training activities in the region are offered by local partners. These training programs are offered at the preschool, primary and secondary school levels. Some notable institutions which participate in these activities are teachers training colleges, community organizations (members), and educational administrators who are sourced at the national and local levels (Vietnam Education Team 2007). Some of the training courses undertaken in Vietnam are thorough and they may range from local training courses to training courses that are undertaken overseas. Most of the teachers have been encouraged to pursue these training courses to the master’s level. The Hanoi pedagogical University has been a pioneer institution in this regard. This institution has sent many teachers abroad for graduate studies through special educational programs.

Another pillar used by the Vietnamese government in implementing inclusion has been materials development. Notably, a series of journals, books and magazines have been published to address concerns about inclusive education in the Asian country. These publications have gone a long way in educating the public about different dynamics of inclusive education such as the existing types of disabilities and how to identify such disabilities (Vietnam Education Team 2007). Therefore, a high level of awareness has been sustained by the publication of these materials. Through the contribution of such materials, effective educational programs (and curricular) have also been developed as a result.

Finally, the last pillar of development has been the inclusion of family and community participation. At the centre of the introduction of family and community participation is the acknowledgement that inclusion is part of community integration. However, at the centre of such a realization is the propagation of the concept of ‘circle of friends’. In other words, the ‘circle of friends’ is considered an important and influential group in the implementation and acceptance of inclusion in the education system because it encompasses the input of the local leaders, teachers and parents.

The Vietnam Education Team (2007) explains that “Participatory workshops and community events bring together relevant stakeholders including parents, teachers, and local administrators to share information, ideas, successes, and challenges of including children with disabilities into the classroom and the community” (p. 6). The inclusion of parents and community members is therefore steered towards making them become active members in their children’s’ educational welfare. This initiative contrasts negatively with the negative parental support that is witnessed in Tanzania. As evidenced in the Tanzanian case, there is very little parental support, while the negative attitudes of community members towards disability also pose a problem to the implementation of inclusion in the East African country.

South Africa

In South Africa, considerable progress has been made towards understanding the concept of inclusion and how it fits into the national educational system. However, the biggest challenge to implementing inclusion in the country was the recognition of the divergent needs existing among students with disabilities (Stubbs 2002). This problem had proved to be difficult for most educationists in South Africa and they proposed the study of all the barriers that existed in the process of implementing inclusion in the country. Through this study, it was explained that class ethos and the educational structure provided the biggest hurdles to the effective implementation of inclusion in the education system. Other barriers to the effective adoption of inclusion centred on barriers to curriculum, social barriers and the lack of clear identification of learner needs (Dovey 1994). Therefore, if the needs of the learners were to be effectively met, these two factors had to change. The elimination of inclusion barriers was therefore adopted as the most effective approach to implement inclusion.

Among the key outcomes proposed through this study was the introduction of centres of learning which will have to be supported by teachers. However, these learning centres were to accommodate community resources and other inputs from specialists. The emphasis here was ‘community input’. It was also proposed that the support centres were also to provide training and support for all teachers and not necessarily for individuals who would want personal training. The management of the inclusion program was also revamped to include the input of teachers, parents and learners (or advocates of education). Apart from managerial tasks, these entities are also free to participate in curriculum development, support system development, and in the teaching and learning process. Finally, it was also proposed that financing, leadership and management also had to be sustained in a long-term manner (Stubbs 2002). These recommendations have since been implemented and they have been largely successful.

Lessons to be Learned

This paper exposes some of the underlying dynamics that ail the Nigerian education system. Some of these weaknesses greatly impede the implementation of inclusion in the western Africa country. It was important to include the history of inclusion implementation in the U.K because the timeline for implementation gives a detailed analysis of the processes experienced and set up by the U.K government to embody inclusion in its educational system as it does today. The history of UK’s journey towards inclusion highlights some of the challenges that Nigeria faces when implementing inclusion and therefore strong comparisons can be drawn between the UK and Nigerian educational contexts. Through this comparison, a cultural theme manifests. The provision of a supportive educational culture not only within the school system but also within the society stands as a strong facilitator for improving the acceptance of inclusion. The importance of having a strong cultural framework for supporting inclusion will, however, be explained further in subsequent sections of this paper but it crowns the importance of understanding inclusion from a holistic perspective as opposed to a purely educational matter (Jenkinson 2000).