Introduction

Measuring expectations for inflation is a complicated and convoluted process that requires a detailed analysis of multiple factors (Iossifov and Podpiera 12), including not only economic, but also political, environmental, sociocultural, and more. (Harris 262). The correlation between the expectations of the target audience and the actual outcomes were spotted quite a while ago by John Maynard Keynes (Barnett 11). However, even though the Keynesian Model seems to have worn out its welcome in the context of the twenty-first century and the global economy, an array of new frameworks has been suggested. The authors considered the New Keynesian model suggested by Gramlich:

(Bryan and Gavin 540). The above-mentioned model was designed to explain the high unbiasedness rates and weak efficiency rates in the forecasts made by the representatives of households, as far as the changes in inflation rates are concerned. The New Keynesian formula that the authors of the paper were trying to create, in its turn was supposed to provide justification for the lack of forecast efficacy in determining the changes in inflation rates, as opposed to the expectations of individuals in the context of a particular household. As Bryan and Gavin make quite clear, there is an evident correlation between the factors mentioned above.

Particularly, the authors of the study were clearly trying to “match the forecast horizon and the sampling frequency” (Bryan and Gavin 542) of the samples studied to understand the efficacy of household expectations, as opposed to professional forecasts. At the same time, the forecast error was identified. As a result, an accurate measurement of the correlation between household expectations and professional forecasts became a possibility (Bryan and Gavin 544).

Main Body

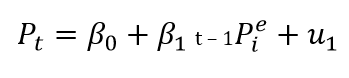

When considering the essential equations that determine the outcomes of the analysis, and can be viewed as the foundation on which the authors could build their approach toward the subject matter, one must mention the New Keynesian Model that was suggested by Gramlich, supposedly created based on the ordinary-least-squares (OLS) estimation of the equation provided below:

In the equation provided above, Pt denotes the inflation rate that is detected over the course of time t. The following expression: (t – 1Pei ) can be defined as the survey forecast designed over the (t – 1) to determine the inflation rates in the designated market, industry, or area. β, in its turn, is the representation of the research hypothesis, β0 being the null hypothesis, and β1 representing the alternative. In the equation provided above, β0 is assumed to equal 0, whereas β1 equals 1. The variable defined as u1 , in its turn, plays the role of a “white noise” (Bryan and Gavin 539) process.

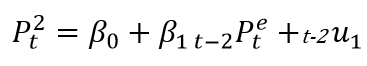

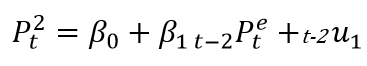

As far as the equation designed by the authors of the article is concerned, the subject matter incorporates the following elements:

as stressed above. While β0 and β1 remain the key hypothesis of the research, the former representing the null hypothesis, and the latter being the alternative, there have been certain changes to the initial model. Particularly, the (t – 2) variable has been included in its framework. As the authors explain, the specified element is supposed to signify that the events under analysis occur within the range of six months. As Bryan and Gavin explain, the formula that they suggest helps prove that the joint hypothesis should be rejected. In other words, the researchers state quite clearly that the correlation between the expectations of household members and the statements made by the authors of professional forecasts do not have as much in common as assumed previously.

Conclusion

Evaluating the implications of the New Keynesian model in the environment of the global economy, as well as the context of a particular local market, one must bear in mind that the contemporary Keynesian frameworks hinge on the notion of a multiplier. In other words, the New Keynesian Model points quite evidently to the fact that an increase in the spending rates within the realm of the modern household triggers an immediate rise in national income levels (Smithers 30).

Therefore, the study shows explicitly that the increase in the national expectation levels may not correlate with the forecasts. Even more surprising, the former, in fact, prove to be moderately efficient, when used both in times of crisis and the epoch of economic stability. The forecasts made by experts, in their turn, seem to fall flat in the instances that can be characterized as crises. The phenomenon above can be explained by the fact that economic models designed in an economically comfortable environment cannot survive the shock of a sudden change in the state of the economy (Bryan and Gavin 543).

Nevertheless, the application of the model as the means of carrying out an analysis of expectations among the members of households may be delayed. Numerous misconceptions about the use of surveys can be considered the reason for the failure to apply the formulas to a real-life scenario. Therefore, a more elaborate framework for promoting the New Keynesian Models in the global and local economies will have to be devised (Alesina and Giavazzi 131).

Works Cited

Alesina, Alberto, and Francesco Giavazzi. Fiscal Policy after the Financial Crisis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2013. Print.

Barnett, William. John Maynard Keynes. New York, NY: Routledge, 2013. Print.

Bryan, Michael F., and William T. Gavin. “Models of Inflation Expectations Formation: A Comparison of Household and Economist Forecasts: Comment.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 18.4 (1986): 539-544. Print.

Harris, Maury. Inside the Crystal Ball: How to Make and Use Forecasts. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 2014. Print.

Iossifov, Plamen, and Jiri Podpiera. Are Non-Euro Area EU Countries Importing Low Inflation from the Euro Area? Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2013. Print.

Smithers, Andrew. The Road to Recovery: How and Why Economic Policy Must Change. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 2013. Print.