Introduction

Comprehensive control over coastal areas is a prerequisite for ensuring the environmental safety of these territories and the effective management of local infrastructure. The Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden (RSGA) area will be analyzed in the context of targeted work undertaken by local authorities and other stakeholders, such as PERSGA, to oversee coastal zones.

To identify the range of activities and determine the responsibilities of specific stakeholders, this is essential to consider the concept of integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) with an emphasis on its functioning in the region under consideration. Appropriate analysis can help identify the specific tasks that the designated boards perform, the existing regulations in force in the area in question, and the anticipated difficulties that may arise soon. The relevant charts and diagrams can be utilized as an evidence base to make the conclusions visually understandable. The role of the ICZM in the control of environmental, transport, industrial, and other types of safety is high, and the example of the RSGA region proves this.

ICZM and the Key Stakeholders in RSGA

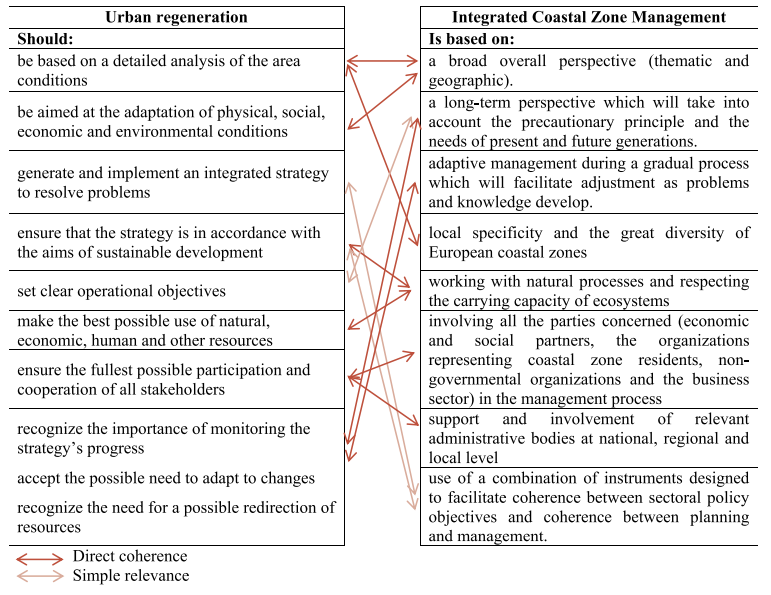

The control of coastal areas to ensure sustainable and safe movement of maritime transport, the preservation of infrastructure, and other important tasks is carried out through initiatives within the ICZM. According to the definition provided by Papatheochari and Coccossis (2019, p. 285), “ICZM is a dynamic, multidisciplinary and iterative process for promoting sustainable coastal zone management”. Particular attention should be paid to the term “integrated” because, in this type of activity, it implies a combination of efforts and different control strategies. Control is performed through vertical and horizontal management systems, which makes it possible to cover the relevant territories comprehensively and ensure the effective implementation of corresponding interventions (Papatheochari and Coccossis, 2019). Moreover, ICZM procedures are often an integral part of the management of initiatives to maintain urban regeneration projects. In Table 1, the relevant links between these two initiatives are shown (Papatheochari and Coccossis, 2019). Based on this information, one can note that a large number of stakeholders are involved in ICZM, and both managerial and legislative regulations are the essential attributes of productive control.

The RSGA region is an area in which ICZM is actively promoted due to a large influx of tourists and a well-developed ship infrastructure. As Kay and Alder (2005) note, this region is one of 14 overseen by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), the organization involved in controlling the adequate implementation of development plans and maintaining a favorable environment. UNEP, in turn, is the initiator of the Regional Seas Program, or RSP, which is engaged in managing coastal areas, including those of the RSGA. At the local level, the Regional Organization for the Conservation of the Environment of the RSGA region oversees all coastal protection management initiatives in the region (PERSGA, 2004). The list of stakeholders includes the local authorities, non-governmental organizations, fisheries unions, and others. Due to sponsorship and funds received in the course of support from the budget, there is an opportunity to implement valuable projects for the protection and development of territories in the RSGA region within ICZM initiatives.

PERSGA and Its Roles

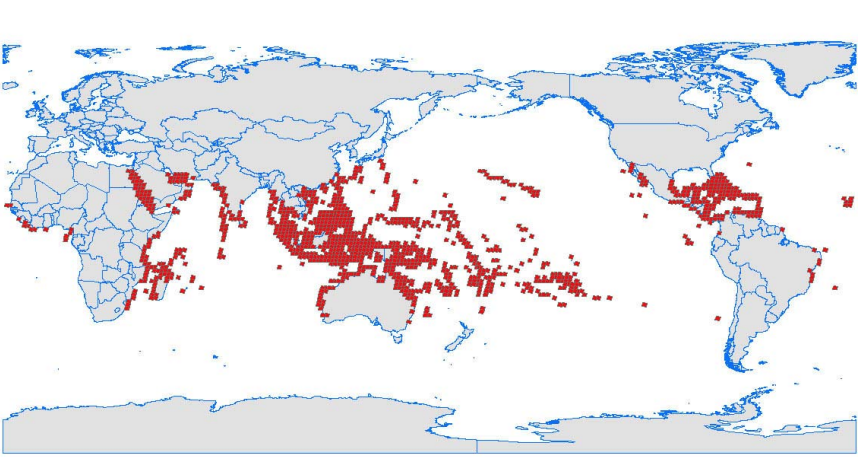

PERSGA is the board that oversees the effectiveness of the implementation of ICZM projects and ideas to preserve an enabling environment in the RSGA region. In Figure 1, a scheme is presented, which reflects the territories under the jurisdiction of PERSGA (Roa-Quiaoit, 2005). Based on this map, one can see that the organization covers a large area in which a few Middle Eastern and African countries are involved. As a result, the scope of PERSGA’s responsibility is high and requires effective control procedures for the timely identification of problem locations and the implementation of projects designed to optimize the state of coastal areas.

The vastness of the territories involved explains the wide range of tasks that PERSGA performs. Based on the scheme presented in Figure 1, in addition to the main functions associated with the supervision of the state of coastal areas, the organization monitors reef sites (Roa-Quiaoit, 2005). This activity requires comprehensive training and, therefore, appropriate financial capacities. While looking at the map shown in Figure 2 shows that, despite the relatively small ocean coverage, the RSGA region is full of coral reefs, which explains the need for skilled monitoring (Khalil, 2014). This scheme explains why PERSGA’s functions are widely required in the areas under consideration and where careful analysis and management are needed.

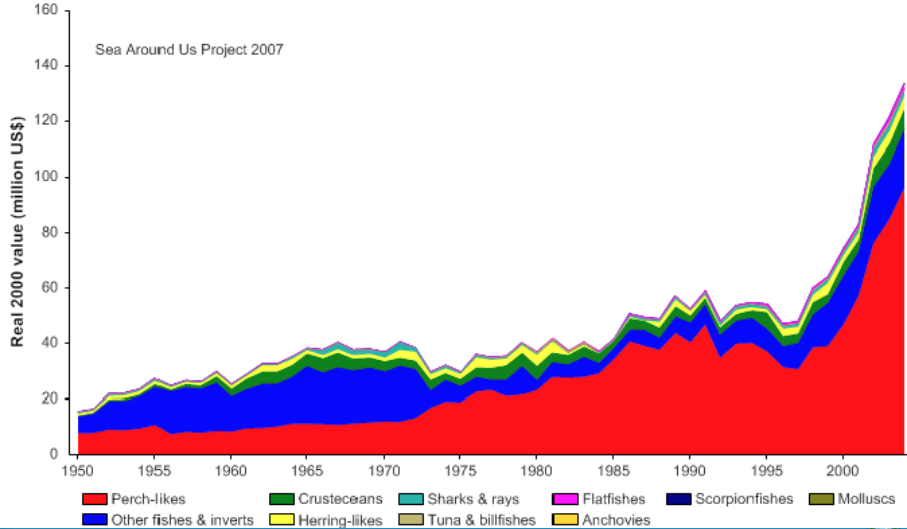

Along with the control of natural issues, PERSGA is actively involved in the commercial field. The organization oversees shipping activities and monitors the share of income generated by fishing in the sea areas in question. Figure 3 shows income dynamics over several decades (Khalil, 2014). This chart demonstrates that by the end of the 20th century, the fishing industry was much more active in the RSGA region than before, which, in turn, was reflected in real income figures. Thus, PERSGA is an important board that performs crucial functions and participates in relevant projects to control and coordinate ICZM initiatives.

Rules, Regulations, and Policies of ICZM

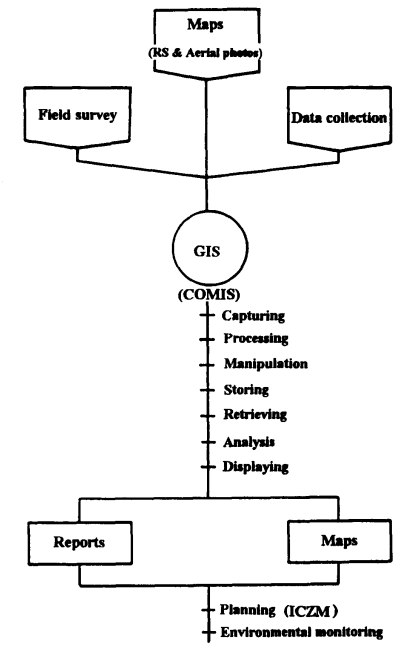

As part of ICZM initiatives, relevant policies and regulations must be respected as rules dictating the nature of interventions and the principles of control implemented by the responsible authorities. In Figure 4, Frihy (1996) shows how the process of setting up steps is built to organize projects and programs in accordance with the planned tasks. This scheme demonstrates the multi-stage nature of tasks to be completed to provide effective and, at the same time, credible interventions designed to eliminate any discrepancies in the calculations and contribute to phased goals implementation. From the technical and economic productivity perspective, this framework is a convenient and efficient guideline.

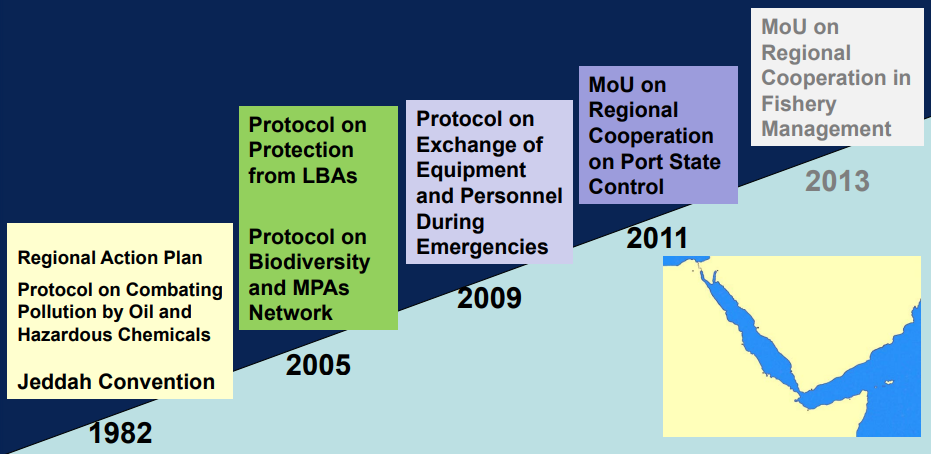

Among the regulations undertaken within the framework of ICZM projects, various initiatives are promoted. For instance, Newton (2006) mentions the principles of organization for controlling bird migration, accounting standards for biogeographic populations, regulations regarding oil production, and others. Since the region under consideration is rich in mineral deposits, particular attention is paid to the rules for establishing the extractive industry, with a focus on the inadmissibility of environmental damage. In Figure 5, Khalil (2014) mentions the list of protocols and action plans initiated by PERSGA since the late 20th century. These policies have become important programs of interaction between stakeholders and have contributed to strengthening the control measures taken for effective financial oversight, climate monitoring, and other necessary tasks.

In the RSGA region, some ICZM initiatives and regulations are curated by the World Bank. Cicin-Sain and Knecht (1998) describe the activities of this board’s individual divisions and note relevant policies aimed at assessing and monitoring the marine biotechnological potential of the RSGA region. Many targeted projects are also funded by the World Bank (Cicin-Sain and Knecht, 1998). Thus, policies and regulations in the territories under consideration are built in accordance with the need to take into account both the laws of the countries involved and the legislative conventions of international agencies.

Anticipated Challenges for ICZM in the RSGA Area

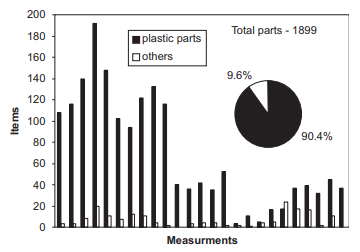

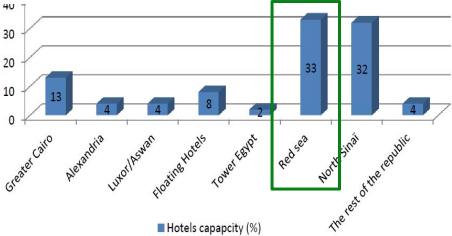

In the next 20 years, ICZM in the RSGA region may face some significant challenges that will have to be overcome to maintain a safe environment. One of the potential issues is the pollution of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Arden. In Figure 6, a chart is shown that reflects the total proportion of contamination at five different locations selected by the researchers (Alkalay, Pasternak, and Zask, 2007). Based on this proportion, one can see that plastic waste is high, which explains the need to take appropriate measures to maintain the cleanliness of the waters in the region in question. Khalil (2014) complements the problem with high tourism activity, which is directly associated with pollution, and provides the distribution of hotels in the Red Sea in Figure 7. These factors are an occasion for PERSGA and other responsible authorities to pay particular attention to the problem of pollution and adapt existing regulations and legislative norms to address the issue. Otherwise, the likelihood of environmental disturbance in the RSGA region increases, which is a threat to biodiversity in the marine areas under consideration.

Despite the existing state borders, this is more difficult to divide marine areas into corresponding territorial units than land. In this regard, the risk of claims by the countries of the RSGA region against each other from the perspective of influence in individual zones may become a problem in the future. The situation may be aggravated by the continuous activities of oil production. According to Kwiatkowska (2001), maritime demarcation should not be an issue associated with the violation of the sovereignty of individual states. Therefore, in the future, within the framework of ICZM initiatives, this may be necessary to optimize the legislation regarding the control over the respective territories and the sphere of some countries’ responsibilities.

Conclusion

The performed analysis has made it possible to identify the significant role of the ICZM concept in the context of coastal territory control in the RSGA region. Relevant government and regulatory authorities, particularly PERSGA, are involved in monitoring environmental, infrastructural, and other aspects of maintaining the safety of maritime areas. The ways of drawing up projects and targeted intervention programs are demonstrated, which are largely related to the economic conditions for the development of the region under consideration. As the anticipated challenges, pollution and problems with the administrative division of territories may arise. The coordinated work of all interested parties is crucial for maintaining the bio-ecological and political balance in the areas under consideration.

Reference List

Alkalay, R., Pasternak, G. and Zask, A. (2007) ‘Clean-coast index – a new approach for beach cleanliness assessment’, Ocean & Coastal Management, 50(5-6), pp. 352-362.

Cicin-Sain, B. and Knecht, R. W. (1998) Integrated coastal and ocean management: concepts and practices. Washington: Island Press.

Frihy, O. E. (1996) ‘Some proposals for coastal management of the Nile delta coast’, Ocean & Coastal Management, 30(1), pp. 43-59.

Kay, R. and Alder, J. (2005) Coastal planning and management. 2nd edn. New York: CRC Press.

Khalil, A. S. M. (2014) Regional indicators used for assessment of the marine environment in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.

Kwiatkowska, B. (2001) ‘The Eritrea-Yemen arbitration: landmark progress in the acquisition of territorial sovereignty and equitable maritime boundary delimitation’, Ocean Development & International Law, 32(1), pp. 1-25.

Papatheochari, T. and Coccossis, H. (2019) ‘Development of a waterfront regeneration tool to support local decision making in the context of integrated coastal zone management’, Ocean & Coastal Management, 169, pp. 284-295.

Regional Organization for the Conservation of the Environment of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (PERSGA) (2004) The Strategic Action Programme (SAP) for the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

Roa-Quiaoit, H. A. F. (2005) Ecology and culture of giant clams (Tridacnidae) in the Jordanian sector of the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea. PhD dissertation. The University of Bremen.