The Haute-monde culture of the post-WWI years is one of the most interesting phenomena, especially taking into consideration the transition from realism to avant-garde in art, literature, and music. This period was marked with the sunrise of a number of styles and directions in architecture, from impressionism to cubism and surrealism. Definitely, this short epoch was marked with a new form of reflecting upon the reality and new vision, and one of its representatives was the outstanding interior designer Jean-Michel Frank. The present paper is intended to discuss his contribution to the development of decorative principles.

Jean-Michel Frank was born in the year 1895 to the family of Parisian intelligentsia. In his childhood, Frank dreamed about a career in law and even began to attend a law school in 1911. His plans for the future were fully destroyed in the year 1915 when both of his older brothers were killed in the First World War and his father committed suicide. Four years later, he experienced a new tragedy, which was the death of his mother in the mental health asylum (Baudot, p. 27; Pile, p.350). The young and immature man thus began to explore the world of French bohemia on his own – it needs to be noted that contemporary Paris was a place of truly cosmopolitan atmosphere, which gathered wealthy emigrants escaping Communism and civil wars. In 1927 he met the person, who appeared to define his further fate, Madame Eugenia Errzauriz, an aged and extremely rich Chilean with a peculiar sense of style (Baudot, p.28; Pile, p.351). She empowered Frank to develop his own ideas of perfect interior and brought him into the contemporary art circle, where he met the decorator Adolphe Chanaux, the painter Christian Berard and architect Mallett-Stevens. As Gray writes, “Frank admired the architecture of Robert Mallett-Stevens and subscribed to his dictum that “you can most luxuriously install a room by unfurnishing it rather than furnishing it” (Gray, p.117). In 1932, Frank signed an agreement with Chanaux to design the latter’s apartment in the Rue de Verneuil. In 1932, they opened a shop and after five years of collaboration, Frank received interior decoration projects from Rockefellers and Guerlains (Baudot, p.38).

It needs to be noted that historically, the 1920s-1930s were characterized by the disappearance of underlined luxury in art, interior design, and fashion. With the fall of the world’s major empires, both interior decorators and their affluent customers were no longer content with the ideas of “royal dwelling” which implied heavy furniture, carpets, and generously embellished details like table legs. Whereas the late “imperial” style conveyed the psychological message about stability and resistibility, the avant-garde in interior design rather implied the volatility of human fate and human powerlessness against global cataclysms (Baudot, p.38). The 1920s-1930s concepts of interior design were to great extent associated with the trauma and exhaustion which resulted from the revolutions and military conflicts as well as with negative anticipations and fears about the future. As opposed to the natural shapes and bright colors of the 19th-century design, the decorators of the 1930s tended to use regular or perfect shapes (e.g. square or rectangular sofas and beds) and combinations of two-three colors. Due to the spread of the ideas of “pure art” or “art for its own sake”, the purpose of interior design changed accordingly. Whereas the earlier decorators approached the apartment as the comfortable and cozy place to stay in and as the means of underlining the owner’s prosperity and great taste, in the 20s-30s interior was viewed as an artwork, which allowed the designer to express their thoughts and feelings. Jean-Michel Frank was not an exception, as he is now often referred to as minimalist or surrealist who designed rooms so that nobody lived in (Owens, 2000; Gray, p.117; Pile, p.351).

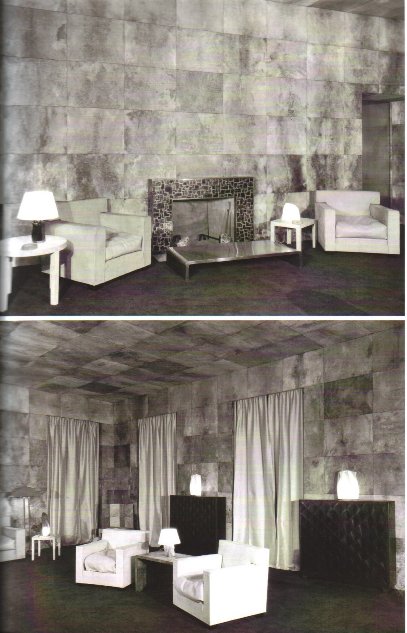

Jean-Michel Frank was amongst the first designers who used free space not merely as the background, but also as the part of his artwork. In fact, space underlined the shape, proportion, extraordinary materials Frank employed (e.g. shagreen, parchment, leather) and the overall atmosphere of “sad beauty” or “somber fantasy”. As Gray recounts, “I was thunderstruck by the economy of the rooms – you could even say their emptiness – but also by their richness and sensuality achieved through the use of wonderful materials covering the walls and furniture” (Gray, p.115). For instance, one of Frank’s well-known works, the Sitting Room in the penthouse of Templeton Crocker (San Francisco) seems at first ascetic in its sparseness; on the other hand, it is extremely rich and elegant due to the designer’s innovative decision to cover ceiling and walls with parchment. The modest, low-key luxury is also represented by the armchairs upholstered in smooth and thin white leather and tables, one of which is covered in bronze, and the other is shagreen. The palette of the room is actually not rich and consists of three colors, dark yellow, white and brown, and the sharp angles of the square armchairs, as well as ideal symmetry, are first to strike the visitor’s eyes; however, there is also a sense of purity, freedom and comfortable solitude, which comes after the visitor notices and touches the texture of the walls and furniture. In fact, the beginning of the 20th century was marked with the emergence of philosophies underlying individualism, which implied that social status should not have dictated compliance with “top circles” lifestyle, habits, and interior. This living room is definitely intended for those personalities, who are perfectly aware of their own self-value and position in society and are self-sufficient and confident enough to avoid demonstrating their wealth to everyone who enters their dwelling.

The Music Room in Cole Porter’s Paris apartment is another distinguishable piece of Frank’s art. The accommodation is filled with a surreal or mystic atmosphere due to the presence of stained-glass windows embellished by white trees, which seem like the natural “drawing” of the rime and resemble ghosts that are about to enter the room. Straw marquetry on the cabinets, parchment on the ceiling, and white leather of finest quality on the sofa serve as the “business card” of Frank’s unique style. Considering this work, one can also approach Frank as a tailor who carefully selects materials and forms to clothe the interior in an appealing way up to the last trifle. “The spare forms of his aesthetic leave no room for a sloppy cut or stitch or edge. No superfluous molding or applied decoration could be employed to hide the lack of skills of the craftsman” (Gray, p.120). Because of the presence of glass windows decorated with mystic trees, the room is perceived as a reliable shelter protecting its visitor from the adversities of the outer world. It might also be viewed as the barrier between the objective reality and the supernatural world, inhabited by ghosts and magicians, so it embodies the transition from one dimension to another. This mood of change and transformation is to great extent consistent with Frank’s experiences about the uneasy contemporary world, whose metamorphoses were caused by industrialization, a radical change of Europe’s political course, and military conflicts.

As one can conclude, the interiors designed by Jean-Michel Frank are not as empty and unsuitable for living as they seem at the first sight. The atmosphere of the his works must be familiar and comfortable to mature personalities whose loneliness is voluntary and whose authenticity consists in their independence and self-sufficiency.

References

Baudot, F. Jean-Michel Frank. Assouline, 2004.

Pile, J. A History of Interior Design. Laurence King Publishing, 2005.

Gray, K. Designers on Designers: The Inspiration Behind Great Interiors. McGraw-Hill Professional, 2003.

Owens, M. “Prolific Genius of Modernist French Design”. Architectural Digest, 2009. Web.

Sitting Room in the penthouse of Templeton Crocker (San Francisco, 1929):