Culture is defined by British Anthropologist, Tyler (1871, 1958), culture is a “complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society”, quoted by Tran (2009, p. 4). Hess and Cateora have defined international marketing as “the performance of business activities that direct the flow of goods and services to consumers and users in more than one nation”, as quoted by Paul (2008, p. 3).

Cultural differences in the international market have posed great challenges to multinational companies. An ethical advert in the UK might be unethical in other parts of the world owing to the cultural differentials between the concerned countries (Paul, 2008).

It is important to understand how cultural differences affect international marketing decisions. Understanding cultural differences gives the benefit of possibly predicting strategic moves of competitors coupled with designing an effective competitive strategy enabling the firm to adapt to such differences (Tse et al, 1988). This paper investigates the significance of culture in the international marketing using the cultural differentials between the UK and other parts of the globe to advise marketers on the best ways to market their products in such markets.

The values and attitudes of the target market may highly influence the consumers’ purchase decisions and dictate the kind of adverts that a company airs (Tran, 2009). Ethical conflicts have been at the centre of business conflicts for multinational companies in the recent past. Given that ethics are highly embedded in the people’s values and attitudes, a marketer must research on the topic before making major marketing decisions.

A case in point is the 2004’s ban of the Nike’s TV advert in China on grounds of insult to the Chinese national dignity. The ad showed a US basketball celebrity, LeBron James, battling with an animated Kung Fu expert, which the Chinese nationals regarded as unethical (Palmatier et al, 2006). The choice of the words is also an important factor to consider when formulating marketing ads to avoid violating the values and attitudes of the concerned country.

An example of an advert that has sparked ethical issues in the recent past is the 2006’s Tourism Australian ad, which was banned in Britain. The advert contained the words, “So where the bloody hell are you?” which were not acceptable in Britain based on the country’s values (Terpstra et al, 2012).

Tran (2009) identifies education and language as key ingredients of the international culture, and he argues that marketers should consider them when making major marketing decisions. In countries with low literacy levels, adverts should be aired orally, through radios, as opposed to written forms. The written adverts require a high level of literacy, and thus, they would not be effective in an illiterate society.

The language in which the adverts are communicated also determines the success of the marketing undertakings. As opposed to the European countries where the curriculum is based on the English language, some countries such as China and the Dominican Republic converse in their local dialects. Therefore, the marketer must understand the language variances and use the appropriate language for the specific country. For example, in the Dominican Republic, an advertiser would use the Spanish language to reach the potential customers while in China the Chinese language would be preferred.

Religions play a vital role in shaping the ethics of a country, and thus, marketers must consider its impacts on their marketing decisions. An advert, which violates or demeans a certain religion, should be avoided since it may lead to successful legal suits or boycotts of the product. An example of the effects of religion on the marketing decision is the 2005 ban on all adverts based on Leonardo da Vinci’s Christ’s Last Supper in the French clothing industry (Czinkota & Ronkainen, 2013).

The Roman Catholic Church went to court seeking an injunction order against the use of the Leonardo da Vinci’s Christ’s Last Supper pictures by marketers in the clothing industry, which was successfully granted. Another example is the ban on all adverts bearing pig portrayals in China in 2007. The Chinese branded the year 2007 as the year of pigs in honour of the Muslims residing in the country (Terpstra, Foley, & Sarathy 2011). All the firms operating in the country were cautioned against using pig portrayals in their adverts.

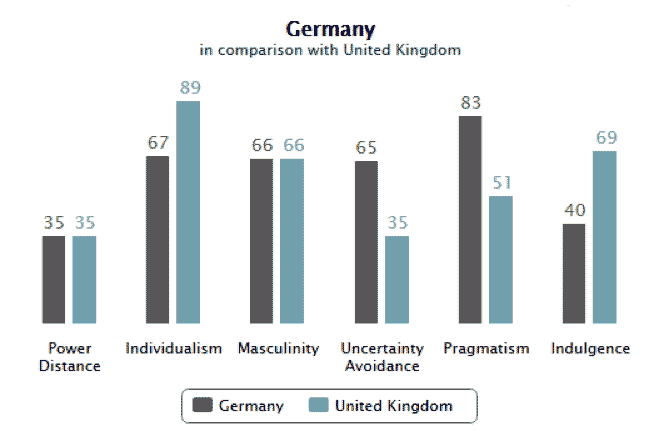

As illustrated in Figure 1, the Hofstede’s cultural model explains the international culture using five dimensions namely power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism, masculinity, and indulgence. Under the model, each of the listed aspects of the culture is examined and rated in percentage.

Uncertainty avoidance refers to the extent to which a certain culture accepts and assumes risks. In some cultures, the level of uncertainty avoidance is high meaning that they are reluctant to embrace risks. Countries with a high score of uncertainty avoidance are less attracted to risky ventures while countries with low scores are ready to assume risks. Countries such as Germany and the Dominican Republic score highly on this aspect meaning that their respective cultures are opposed to risky ventures.

As illustrated by Figure 2, Germany scores higher in this aspect as compared to the UK. Therefore, if a UK multinational company plans to market its products and services in Germany, it has to convince its customers that the products are free of risks (De Mooij & Hofstede, 2011). Besides, given that the contemporary globalisation is highly achieved through mergers and acquisitions, a UK company planning to merge with a German company must come up with a well thought and risk-free deal.

The power distance aspect of the Hofstede’s cultural dimensions refers to the degree to which individuals and organisations believe and respect the unequal distribution of power and hierarchy in a country or organisation (Yaprak, 2008). Britain scores 35% on this aspect, which implies that hierarchy is not much respected. However, in other countries such as China and the Asian countries, the culture advocates high respect for leaders.

A high score concerning the power distance aspect implies that the country highly respects power distribution and hierarchy. For a marketer to succeed in a highly power distanced society, the adverts must show social class awareness. For example, a marketer may use the portrayals of the most successful persons in the society in the advertisements.

The concept of individualism implies that individuals in the society do not largely depend on each other during their daily activities. However, in a collectivist society, people tend to be dependent on each other. Marketers must consider the individualism or collectivistic nature of a country to make informed decisions. In an individualistic culture, a marketer should target individuals in the adverts. On the other hand, in a collectivist culture, the marketer should target groups.

Therefore, the marketer must consider social classes when making such adverts. Besides, the collectivist cultures prefer personal advertisement to the other forms of promotion (Czinkota & Ronkainen, 2013). Therefore, the marketer in a collectivist culture must seek to establish personal relationships with the customers to gain their loyalty.

Masculinity refers to the degree to which the society values and measures the success of individuals or groups in the society. This dimension measures the level of competition among the various players in the economy or an organisation. Yaprak, (2008, p. 219) quotes that a “high score of masculinity implies that the concerned society values competition, achievement, and success”.

For countries with high masculinity scores, the marketer must design the marketing message in such a way that it convinces the customers that the product is the best. In a highly masculine nation, the people tend to value quality (De Mooij & Hofstede 2011).

The indulgence dimension refers to the degree to which individuals tend to control their desires and impulses based on their childhood experiences. This dimension may be described as either low or high depending on the ability of the concerned people to control their desires. A low score for this dimension denotes a weak ability to control one’s desires while a high score implies that the concerned individuals have a strong ability to control their desires (Yaprak 2008).

The marketer needs to consider the level of indulgence for the target group of customers to succeed in their marketing campaign. For example, Germany has an indulgence score of 69% as opposed to the UK’s 40%. Therefore, it may be argued that the Germans have a greater tendency towards cynicism and pessimism as compared to the Britons (De Mooij & Hofstede, 2011).

To accommodate the population, a UK marketer has to analyse the possible risks comprehensively and define the mitigation measures put in place. The marketer should emphasise the available customer support mechanisms to persuade the customers to buy the product.

Culture is an important aspect of international marketing in the contemporary society. If businesses want to succeed in their globalisation agendas, they have to be culture sensitive otherwise they might cause offense leading to failure. This paper has explored the importance of culture in shaping the marketing undertakings of a firm. The paper has highlighted four major components of culture including values and attitudes, education, language, and religion.

Moreover, the paper has analysed the impact of culture on marketing using the Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. The conclusion is that culture plays a vital role in the success of a firm’s marketing campaign.

List of References

Czinkota, M., & Ronkainen, I., (2013) International marketing. Cengage Learning. Boston.

De Mooij, M., & Hofstede, G. (2011) ‘Cross-cultural consumer behaviour: A review of research findings’. Journal of International Consumer Marketing. Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 181-192.

Paul, J., and Kapoor, R. (2008) International Marketing: Text and Cases. Tata McGraw-Hill. New Delhi

Palmatier, W., Dant, R., Grewal, D., & Evans, K. (2006) ‘Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: a meta-analysis’. Journal of marketing. Vol. 70, No. 4, pp. 136-153.

Terpstra, V., Foley, J., & Sarathy, R. (2012) International marketing. Naper Press. Nebraska.

Tran, T. V. (2009) Developing cross-cultural measurement. Oxford University Press. New York.

Tse, D. K., Lee, K., Vertinsky, I., and Wehrung, D. A. (1988) Does Culture Matter? A Cross-Cultural Study of Executives’ Choice, Decisiveness, and Risk Adjustment in International Marketing. Journal of Marketing. Vol. 52, No. 4. American Marketing Association.

Yaprak, A (2008) ‘Culture study in international marketing: a critical review and suggestions for future research’. International Marketing Review. Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 215-229.