Introduction

Jainism is a religious system based on the insights of twenty-four enlightened ‘conquerors’ who taught the way to salvation. The twenty-four are more commonly known as tirthankaras for they crossed the turbulent ocean of the material world to reach the safe shore of enlightenment and perfect bliss. Jains hold that other men and women can achieve enlightenment, but the twenty-four tirthankaras are revered for their special qualities and attributes, most notably their ability to instruct their contemporaries and help them to achieve emancipation. Jainism is a system of practices for enlightenment; all other aspects (temples, idols, rituals, clothing and food customs, the extensive cosmology) are subsidiary.

History

In India, Jainism appeared several thousand years ago, but the exact date tracked back to life and teaching of Parshvanatha. The major division within Jainism that between the Shvetambars and Digambars–was firmly established by the fifth century; and according to Jain tradition this was not the first but the eighth major schism to have occurred within the fold. Schisms have occurred with impressive regularity, and new groups continue to appear, so that today there is quite a range of contending traditions practising and preaching subtly different versions of Jainism (Sanghivi 54).

Temple worship has always been controversial in Shvetambar Jainism, and there is a fairly continuous tradition of organized opposition. which goes back at least to the fifteenth century, when the Gujarati layman Lonka Shah claimed to have discovered in ancient texts that the practice was illegitimate. He founded a new sect, the Lonka Gacch, from which the Sthanakvasis and Terapanthis of today are descended. These traditions are influential, although they have fewer followers than the Mandir Margi traditions (Sanghivi 58). The Terapanth especially is skilful at projecting itself as a modern movement, and as representative of Jainism as a whole in national and international religious fora.

So the Mandir Margi schools, such as the Tapa Gacch and Khartar Gacch, maintain their practice of temple worship against the opposition from these traditions, as a deliberate and sustained choice. The renouncers, although they are restricted by their monastic vows in the role they may play in temple ritual, are none the less vociferous in providing, in print and in their sermons, powerful intellectual justifications for the practice, and replies to the arguments of rival schools (Cort23, 31).

The Shvetambar Terapanth was founded in the eighteenth century in western Rajasthan, by a disillusioned Sthanakvasi renouncer who is now known to his followers as Acarya Bhikshu. Like the tradition he came from, Bhikshu was opposed to the worship of temple idols, but he also objected to the way Sthanakvasi renouncers lived in halls built specially for their use, and prescribed instead that his disciples should sleep in the homes of lay followers.

He had some distinctive teachings about non-violence, and the relation of Jainism to social ethics, which will be discussed below (Sanghivi 61). The Terapanth has come to have a distinctive organization too. Whereas in all other Shvetambar traditions renouncers live under the authority of their own guru, and small travelling groups have day-to-day autonomy from the most senior renouncers (acaryas) of the tradition, the Terapanth is a single, tightly-run sect, in which all renouncers are answerable to a single acarya. The present leader, Acarya Tulsi, has been particularly effective in using the modern mass-media to raise the public profile of this sect in India (Cort23, 33).

The Kanji Swami Panth, though formally Digambar, pursues a vigorous proselytizing campaign whose targets include Shvetambars and also non-Jains. Although it does give formal recognition to Digambar monks, this sect does not have renouncers of its own and is led instead by lay pandits, who give lectures and conduct study sessions to promote its views (Sanghivi 51). It was founded in the mid-1930s by a Shvetambar monk from southern Gujarat, who switched allegiance, declaring himself a Digambar layman. It is now influential in Jaipur through its alliance with a local Digambar group there, the followers of the eighteenth-century Jaipur layman, Pandit Todarmal.

Like Kanji Swami (and like Banarsidas, another lay reformer of a century before him Todarmal was influenced by the mystical doctrines attributed to the second-century Digambar saint Kunda Kunda (Dundas 101). This movement does not oppose temple ritual–its followers worship in Digambar temples–but its teachers concentrate on the dissemination of the Kanji Swami version of Jainism, which differs distinctly from that taught by the Mandir Margi traditions. This they do in Jaipur from a well-organized, entirely lay organization running an extensive publishing and teaching programme in Todarmal’s name.

The Khartars opposed the so-called temple-dwellers, and argued that laxity in this area led to attachment to material possessions, and so to disregard for other rules on non-violence and receiving alms (Sanghivi 84). In 1024, it is said, king Durlabha arranged a public debate at Anahillawara Patan, between the itinerant renouncer Jineshvar Suri, and Sura, a prominent temple-dwelling monk. Not only did Jineshvar defeat his opponent, but the king bestowed on him the epithet ‘Khartar’–sharp-witted and fierce–and from this the present order takes its name (Cort 41).

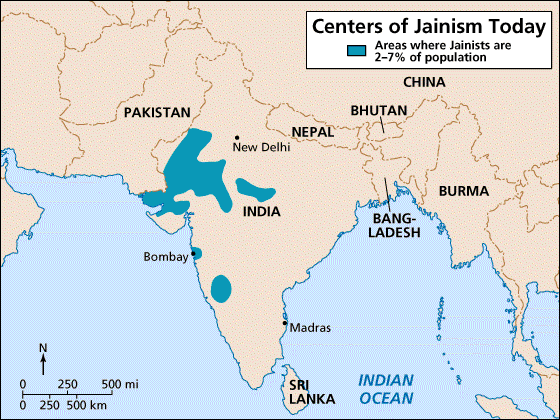

At a little over three million, they make up less than a half of one per cent of the population of India (see appendix 3). They are to be found in very small numbers in all parts of the country, but are concentrated in three large home territories. Jains living elsewhere tend to think of themselves as coming originally from one of these areas, and often look there for marriage partners. The first of these regions is in the Deccan, where the greatest concentration of Digambars lives. There are, it seems, whole districts in this region where the majority of Jains are farmers, and where Jain farmers make up the majority of the population (Dundas 101).

The second area concerned with, is a wide band stretching across north- western India, encompassing the cities of Delhi and Bombay, the states of Rajasthan and Gujarat, and the contiguous areas of the Punjab, Haryana, and Madhya Pradesh. This is where the main concentration of Shvetambars is to be found, although even here the population is unevenly spread. Certain villages and small towns are predominantly Jain, but no whole District has a Jain population which exceeds 7 per cent of the total (Cort 39). The third region covers Delhi, the eastern parts of Rajasthan, and the neighbouring parts of Madhya Pradesh, so it overlaps with the eastern end of the Shvetambar block. Jainism drew its first supporters from among urban peoples, largely traders and merchants–from the same milieux, in fact, as did Buddhism.

The social homogeneity of the lay Jain community in subsequent millennia has sometimes been exaggerated, but the extent to which Shvetambar Jainism especially has remained a religion of the commercial élite is by any standards remarkable. Such references as there are to lay Jains in the Shvetambar canon simply presume that those who are not kings will be wealthy merchants (Sanghivi 97).

Jains can be described as men and women who have left their families and given away all their material possessions to lead a wandering life of asceticism and religious teaching. There are several different Jain traditions, and the rules which renouncers follow vary between them, but in all cases the life they prescribe is one of justly famed severity. Jains make a distinction between soul and non-soul, between living and dead.

All souls are eternal and uncreated, simply existing, like the universe they inhabit (Sanghivi 87). This universe is a physical structure, composed of non-living (ajiva) matter and of finite, though immense, size. It is shaped roughly like a man, his legs astride, his hands on his hips. In the centre, at about the ‘waist’, lies our layer of the universe. In the centre is Mount Meru, and surrounding it are seas and continents arranged in concentric circles. Part of one of these continents is the land we inhabit, Bharata, the land that was home to the Jain cosmologists and into which the twenty-four tirthankaras were born.

Other tirthankaras are born in other continents in such a way that there is always a tirthankara preaching in the realms men inhabit: emancipation is possible, and correct action in Bharata can lead to rebirth in such a place (Dundas 104).

Some parts of the continents, including Bharata, are subject to fluctuations in the time cycle of the universe, such that the possibility of the birth of a tirthankara and the emancipation of men is possible at a time in which happiness and unhappiness are present in more or less equal proportion: too much of one or the other and the human race is not capable of producing those giants who are able to appreciate both the transience of worldly happiness and the possibility of unalloyed bliss. Other continents, however, perpetually bask in the right balance, and there is always a tirthankara there, preaching liberation (Cort 49). The main symbols of Jainism are swastikas and The hand with a wheel on the palm (see appendix 1,2).

Gods inhabit the heavens and the first of the hells, while demons inhabit the other six hells. Good or bad actions in this world can lead to rebirth in these realms. Above the highest heaven, at the very top of the universe, lies a crescent-shaped beliefs, the resting place of emancipated souls. When the soul is freed from karma it rises through the universe to inhabit this region (Shah 77). In this way Jainism differs from, for example, Hindu schools of thought which either do not view all souls (of men, gods, animals, demons) as interchangeable (one soul can exist in all states serially), or else perceive the universe as an expression of some higher being (Sanghivi 99).

That is to say, in doctrinal Jainism there is no distinction made between the mundane and the transcendental: the universe, and everything in it, is knowable and classifiable; even the experience of omniscience and emancipation is described and documented. This is the source and centre of Jain ‘atheism’–there is for the Jains no supreme transcendent being in the universe, nor any means of divinely assisted salvation. The tirthankaras (and other liberated souls) once emancipated, are unable to intervene in the affairs of men and the universe, for this would involve action and re-entanglement with karma. Larger local Jain communities maintain buildings called upashrayas, often attached to temples, for renouncers to lodge in (Shah 82).

In sum, Jainism is one of the oldest religions in India based on century old traditions and unique beliefs. Jainism is at its most distinctive on two counts: in its conceptions of the universe and of the soul. Souls for the Jain philosophers are discrete, pure entities, without weight or size but conforming to the shape of the body they inhabit, and are fundamentally immutable. They are all, however, barring those that have achieved emancipation, contaminated by non-soul matter (karma) which ties them to the world, to the cycle of life and death.

Works Cited

Cort, J. E. Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press, USA, 2001.

Dundas, P. The Jains (Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices). Routledge; 2 edition, 2002.

Sanghivi, J. S. A Treatise On Jainism. Forgotten Books, 2008.

Shah, N. Jainism : The World of Conquerors. Sussex Academic Press, 1998.

Appendix