Introduction

The purpose of this research paper is to determine whether juveniles who stay in boot camps for an extended period will practice recidivism. Juvenile boot camps are described as prison programs that incorporate military training to reduce recidivism among juveniles who have committed wrongful acts (Meade & Steiner, 2010). These activities involve a lot of vigorous physical work, such as drills, manual labor, and challenging exercises.

Boot camps are usually governed by strict rules that the juvenile delinquents are required to follow to avoid severe punishments that are meted on those who break the rules. These boot camps are usually operated by the state or federal governments, and they are run by correctional officers who act as drill instructors (Tyler et al., 2001).

After the Office of Juvenile and Delinquency Prevention started juvenile boot camp programs in 1992, these camps have continued to proliferate in the United States to deal with the growing numbers of juveniles who are caught up in violent crimes (Ashcroft et al., 2003). The boot camp programs differ in numerous aspects such as how old the juveniles in the boot camps are and their backgrounds, how strictly the program will follow the military model, the capacity of the boot camp, and how many juveniles it can accommodate at a particular time, the cost of accommodating each juvenile, the rates of recidivism in the boot camps and the type of aftercare that is provided to the juveniles in the boot camp (Anderson et al., 2000).

Research that has been conducted on juvenile boot camps is limited, and there exists insufficient data on the subject to make any definite judgments or arguments. This is mostly attributed to the fact that boot camp programs are relatively new concepts because they were started in 1992. The limited studies that have been conducted on the topic have shown that there is no general consensus on whether juvenile boot camps reduce the rates of recidivism.

The underlying concept behind establishing these programs was to reduce overcrowding in prisons and provide rehabilitation centers for young adults who had been caught on the wrong side of the law. Boot camps were also started to reduce the rising costs by the correctional systems and also reduce the increasing rates of recidivism amongst juveniles (Parent, 2003).

Literature Review

The correctional system in the United States came up with juvenile boot camps’ concept to deal with the rising cases of juvenile arrests. Boot camps were viewed as shock incarceration techniques that have been in use since 1983 (Klein, 2010). Most of the research conducted on the subject of boot camps have been based on adult camps and how these camps affect recidivism rates. There is, however, limited data on boot camps for juvenile delinquents and whether these camps affect the rates of recidivism amongst juvenile offenders (Ashcroft et al., 2003).

According to Steiner and Giacomazzi (2007), some cases of juvenile boot camps have generated differences in the rates of recidivism or the length of time that it takes a juvenile offender to commit an offense once they are released from prison. This rate of recidivism has been compared to that of traditional facilities such as prisons or detention centers. Some studies have revealed that juveniles who do not adapt to boot camps’ environments are more than likely to recidivate once they are released.

A study conducted by William and Mackenzie (cited by Steiner & Giacomazzi, 2007) on the time frame of recidivism has shown no effect on the length of time a juvenile spends in the boot camp in relation to the rate of recidivism. However, they noted if the juvenile offender released from prison was involved in some aftercare programs, then the risk of the recidivating was less than likely.

Recidivism is defined as the tendency to go back to criminal patterns or activities that led the offender to be locked up in prison or a boot camp (Merriam-Webster, 2010). To understand recidivism, three concepts that underlie recidivism have to be assessed. The three ideas are the time frame of recidivism, which is termed as recidivism, and what basis can be used to make sense of the information used to explain recidivism. Recidivism is viewed in different contexts depending on the correctional system that is in place in the various states in the U.S. For example, the Department of Corrections in Florida views recidivism as returning an offender to prison with a new sentence. In contrast, the Colorado prison system views recidivism as criminal offenders who have carried out violations that are technical (Beck, 2001).

The time frame for recidivism that has been identified in the majority of the U.S. prison systems is one to 22 years. This time frame is measured from when the offender is released from the boot camp, detention center, or prison. The interpretation of recidivism data involves comparing the available information on the subject (Benda et al., 1996). A significant challenge of gaining data on recidivism rates is that focusing on one boot camp program does not provide accurate statistics of the number of juveniles who become repeat offenders. To make sense of recidivism rates, comparisons have to be made with other similar programs to gain accurate data on the subject (Camp & Camp, 1998).

According to McNeely (2009), juvenile boot camps are tools used by governments to deal with young people’s crimes in society. Youth crime is viewed as the result of various factors, including lack of employment, poverty, lack of proper education, peer pressure, lack of social support from family members, and society.

Rehabilitative programs have been viewed by many correctional systems to be the most effective in dealing with young people caught up in criminal activities as they offer counseling and educational programs. However, society views these programs to be ineffective in deterring criminality amongst the youth, which pressurizes the government to send these criminals to boot camps (Benda & Toombs, 1997).

McNeely (2009) views boot camps as ineffective and harmful tools used to reform juvenile delinquents because of the lack of rehabilitative and educational programs. Tyler et al. (2001) note that because of the heavy reliance on military structures, juvenile boot camps make it impossible to reform the delinquents as they mostly address aspects of discipline and respect instead of improved behavior. The military system used in these camps is based on following strict rules and guidelines, making it difficult for the correctional officers to counsel the youth about their delinquent activities (Tyler et al., 2001).

Mackenzie et al. (2001) note that juvenile boot camps have remained controversial, especially in the penal and correctional system. Criticism has arisen because of the military structure used in these camps to manage the juvenile offenders and the preceding behavior that led them to commit criminal acts. Researchers into the topic have viewed the military-style use to be less accommodative to reform and rehabilitation programs as military structures mostly involve the use of fear tactics to deal with people (Gover et al., 2000).

According to a report published by the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS), juvenile boot camps incorporate therapeutic programs which often fail because of the difficulty in switching from the military environment to a counseling environment. Many of these boot camps lack qualified personnel to carry out the counseling and reform programs as they are mostly trained to ensure military discipline in the boot camps (McNeely, 2009).

Methodology

The purpose of the study is to determine whether the length of time juveniles spend in a boot camp leads to recidivism. The research will involve analyzing juvenile offenders in boot camps and recidivism rates in these boot camps by looking at the dependent and independent variables. The sample size used in the research study will involve 100 juveniles in boot camp systems based in California, New York, Louisiana, and Colorado.

The sampling method that will be used will be stratified sampling, which reduces the chances of errors occurring during the sampling process. The data collection technique will involve questionnaires, while the research design will be experimental, where control and intervention groups will be used. Therefore, the hypothesis of the research study will be used to determine the results of the investigation.

Research Question: How effective are Boot Camps for Juvenile Offenders?

Hypothesis: The longer the juvenile stays in Boot Camps, the less likely the rate of recidivism.

Unit of Analysis and Variables

According to Yurdusev (1993), the unit of analysis is viewed to be the main factor under assessment or study in research programs. The unit of analysis for this research paper will be the length of time juveniles spend in boot camps. The independent variable for the study will be juvenile boot camps based in California, New York, Colorado, and Louisiana, while the dependent variable will be recidivism. The reason for choosing boot camps as the independent variable is because the data collected on the research can be manipulated by the researcher to reflect the relationship that this variable has with the dependent variable (Changing minds, 2010).

The dependent variable will be conceptualized in terms of looking at the factors that lead to recidivism, including relapse into criminal activities, repeat offenses, or re-offensive criminal behaviors. The independent variable will be operationalized by looking at the time frame of recidivism. The rate of recidivism is analyzed in juveniles who have been released from boot camps within one year.

Sampling Techniques, Sample Size and Sampling Frame

The probability research design will be used to determine the sample size of the population because it has a non zero probability of each member of the population being chosen for the study (Research methods, 2006). Stratified sampling will be used to research the four boot camps based in California, Louisiana, Colorado, and New York. Stratified sampling is a vital sampling technique because it reduces sampling errors from occurring, and the sample information collected from the various boot camps is similar (Holton & Burnett, 1997).

The sample size for the research will include 100 juveniles in boot camps that are based in four states: New York, Louisiana, Colorado, and California. These four states were chosen because they represented the population of juveniles in boot camps. The sampling frame is viewed to be a representation of the population that is under study (Statistics, 2010). The sampling frame for this study will be juvenile offenders, juvenile offenders that have completed boot camp, and juveniles who have been out of boot camp for at least one year.

Experimental Design

The experimental design for this study involved static groups where one group is exposed to the research conditions. This group is known as the intervention group, while the other group, known as the control group, does not undergo any experimental activity or testing. Experimental designs are the most rigorous and reliable of all the research designs as the static groups are based on many variables and data collected from a large number of participants. Static groups in the experimental design are also important because they show the behavior of members in both the control and intervention groups (Trochim, 2006).

Data Collection and Analysis

The data collection technique that will be used for this study will be quantitative data collection. Quantitative research involves the use of data collection techniques that are designed to be objective and relevant, and reliable. It is concerned with the testing hypothesis derived from theoretical frameworks to estimate the relationship between the dependent and independent variables (University of Wisconsin, 2010). The data collection techniques will cover how the participants under study will randomly be selected from the study population in an unbiased manner. Quantitative data collection methods are preferable because they produce results that can be quantified and correlated. The techniques used in quantitative data collection involve the use of surveys, interviews, and questionnaires (Weinreich, 2010).

The most appropriate quantitative technique for this study will be the use of standardized or paper questionnaires that will be able to reach the sample size within a limited amount of time and with limited resources (Statistics Canada, 2010). Questionnaires are also preferable because participants in the research are more likely to provide truthful information regarding controversial issues related to boot camp programs (Leedy & Ormrod, 2001). The questionnaire will incorporate closed response questions to obtain the best possible answer.

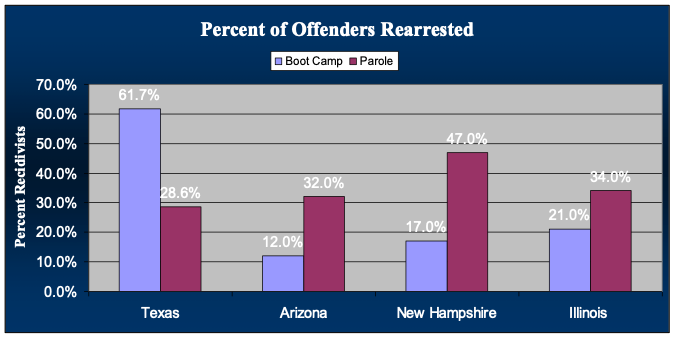

The statistical method used to analyze the information will involve graphs that provide the percentage of juvenile offenders who have been arrested again after being released from a boot camp. The graph used in this study showed inconsistency with the boot camp programs used in the states under analysis and the rate of recidivism. The recidivism rate in juvenile offenders who were in boot camps was lower compared to those in a regular correctional facility. The graph shows no notable difference in the recidivism rate between juvenile boot camps and traditional programs.

Political and Ethical Considerations

Ethics has to be observed when conducting research studies to ensure that the information provided in the research is objective, honest, truthful, and free from any bias. The Social Research Association (SRA) states that any research activity that is viewed to be beneficial to individuals, groups of people, or the society should be conducted responsibly and ethically. Researchers should observe scientific standards when conducting their research, especially when carrying out data collection and analysis procedures (SRA, 2003, p.13).

This research study will not physically or psychologically harm the subjects under investigation, and their participation will be voluntary. This will, therefore, not affect the moral and legal order of carrying out the research. The correctional officers and the juveniles’ parents will sign a waiver for them to participate in the study. This will ensure that there is full consent from the parties under research and provide the research results have been obtained with integrity.

Conclusion

The study showed no conclusive information about whether juveniles who stayed in boot camps for an extended period were likely to recidivate. The literature review has also demonstrated the varying opinions that different researchers have on whether boot camps reduce recidivism in juvenile offenders. Some researchers have argued that the only way to reduce recidivism is to create aftercare programs to ensure the juvenile offender does not recidivate to criminal activities.

Others have argued the length of time juveniles spend in boot camps does not reduce recidivism rates. Despite the limited research conducted in the field, most of the researchers have concluded that boot camp programs do not reduce recidivism rates. The only means of determining whether these programs reduce recidivism rates is to continue conducting more research in the field.

References

Ashcroft, J., Daniels, D.J., & Hart, S.V., (2003). Correctional boot camps: lessons from a decade of research. Washington, D.C. : U.S. Department of Justice.

Anderson, J. F., Laronistine, D., & Burns, J.C. (2000). Boot Camps: An Intermediate Sanction. Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol.28, No. 4, pp. 337-338.

Beck, A.R. (2001). Recidivism: a fruit salad concept in the criminal justice world. Web.

Benda, B.B., & Toombs, N.J., (1997). Testing the deviance syndrome perspective among boot camp participants. Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol.25, No.5, pp. 409-423.

Benda, B.B., Toombs, N.J., & Whiteside, L., (1996). Recidivism among boot camp graduates: a comparison of drug offenders to other offenders. Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol.24, No. 3, pp. 241-253.

Camp, C., & Camp, G. (1998). The corrections yearbook. Middletown, Cincinnati: Criminal Justice Institute.

Changing minds (2010). Variables in research. Web.

Gover, A.R., Mackenzie, D.L., & Styve, G.J., (2000). Boot camps and traditional correctional facilities for juveniles: a comparison of the participants, daily activities and environments, Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol.28, No.1, pp. 53-68.

Holton, E. H., & Burnett, M. B. (1997). Qualitative research methods. In R. A. Swanson, & E. F. Holton (Eds.), Human resource development research handbook: Linking research and practice. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Klein. M.J., (2010). Florida’s Juvenile Boot Camps: A Comparative Evaluation. Web.

Meade, B., & Steiner, B., (2010). The total effects of boot camps that house juveniles: a systematic review of the evidence. Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol. 38, No. 5, pp. 841-853.

Mackenzie, D.L., Gover, A.R., Styve, G., & Mitchell, A.O., (2001). National study comparing the environments of boot camps with traditional facilities for juvenile offenders. Web.

McNeely, A. (2009). Are boot camps effective? Combating youth delinquency with correctional camps. Web.

Merriam-Webster (2010). Online Dictionary Recidivism. Web.

Parent, D.G. (2003). Correctional Boot Camps: Lessons from a Decade of Research. Web.

Research Methods (2006). Non-probability sampling. Web.

Social Research Association (SRA) (2003). Ethical guidelines. Web.

Statistics Canada (2010) Research methods. Web.

Statistics (2010). Statistical glossary: sampling frame. Web.

Steiner, B., & Giacomazzi, A.L. (2007) Juvenile waiver, boot camp and recidivism in a Northwestern state, The Prison Journal, Vol.87, No.2, pp. 227-240.

Trochim, W.M.K., (2006). Experimental design. Web.

Tyler.J. Darville, R., & Stalnaker, K., (2001). Juvenile boot camps: a descriptive analysis of program diversity and effectiveness. Social Science Journal, Vol.38, No. 3, pp. 445-460.

University of Wisconsin (2010). Data collection methods. Web.

Weinreich, N.K., (2010). Integrating quantitative and qualitative methods in social marketing research. Web.

Yurdusev, N. (1993). Level of Analysis and Unit of Analysis: A Case for Distinction. Disclosure, Journal of International Studies, Vol. 22, No.1, pp 77-88.