Introduction

Economics connects itself with economies all over the globe commencing from how the goods and services are produced in a society to how the consumption is done. Economics has also powered the global finance in a number of junctions in history and is an essential part of humankind’s day-to-day lives. In his research on the subject, Defermos’ says, “Because economic agents are not able to know whether these contracts will be ultimately honored, perceived uncertainty influences their willingness to enter into them with profound implications for macroeconomic performance” (2012, p.750). Assumptions that conduct the analysis of economics have been altered throughout history. This paper will focus on matters of the history of economic thought using Heilbroner’s (1999) work as a firm basis of its argument since the author is well renowned for his mastery of the subject. Specifically, it will address the Keynesian theory and its view of liquidity preference in an attempt to find out why people and organizations would wish to have their property in liquid cash rather than banking it in a savings account.

Liquidity Preference

As Heilbroner (1999) says, self-centeredness and struggle for survival distinguishes people’s behaviors from those of other creatures (p.18). The economic concept of the new classical economist, Keynes, otherwise known as the Keynesian theory, focuses on the liquidity preference of money at the individual and national level. However, Keynes argues that only three causes can result to the holding of money: the motives of transaction, precaution, and speculative (whereby money is held as a quality of riches). According to Keynes (1932), liquidity preference is the reasons why people prefer to have their assets in the form of liquid cash instead of putting the money in a savings or demand deposit bank account where it can earn some interest income. As an example to elaborate liquidity preference, treasury bonds for three, ten, and thirty years may be required to disburse interests of 1%, 3%, and 4% respectively. Defermos concurs with this argument by positing, “Higher financial obligations increase, ceteris paribus, the possibility of debt repayment difficulties; because money is a safe asset for honoring debt commitments” (2012, p. 755). It is also referred as the inverse relationship between demand for money and interest rates.

The liquidity preference of an individual depends on three considerations. Firstly, it depends on the transaction demand for money, which relates to money demand in the current transaction of individuals. It is money kept in hand to meet current expenditure like the purchase of glossaries, money for transport, and so on. In a firm, this cash could be the money used for the purchase of every day inputs used in the production of goods and services. It is elastic to the level of real income because the higher the income earned, the more the day-to-day expenditure for the individual. Secondly, precautionary demand for money is the desire of people to hold cash for unforeseen contingencies (inventory/possibilities). For instance, people hold a certain amount of money to provide the danger of unemployment, sickness, or any other unexpected incident that may occur. The amount of money demanded for this motive depends on the type of conditions that surround the individual and the level of income. Just like the transactional demand for money, it is inelastic to the interest rates. In this concept, the transaction and precaution demand for money are summed up together as M1. Lastly, speculative demand for money relates to the desire to have an individual’s resources in liquidity form in order to take advantage of the market movement regarding the future changes in bond prices.

If bond prices are expected to increase, interest rates are expected to reduce. Therefore, individuals buy bonds to sell when the bond price increases and vice versa. This motive is an increasing function on the rates of interest. It is inelastic to the levels of income(Y) that depends on interest rates (r). Speculative demand for money is M2. Therefore, if the demand for money is MD, then MD= M1 + M2. People hold money for speculative purposes due to the uncertainty about future interest rates. Fall in interest rate leads to increase in speculative demand for money. Thus, it is a function of interest rates. The liquidity preference curve becomes quite perfectly at a very low rate of interest. It is horizontal towards the right hand side. The perfectly elastic position of the liquidity preference curve indicates that people will hold with them as inactive balances of any amount of money that they will have. This concept is called the liquidity trap, which is the point at which expansion in the money supply is trapped in the sphere of the liquidity trap. It is worth noting that this case cannot affect the interest rate or the rate of investment.

Liquidity Trap and Inflation

According to Keynes (1932), because of the existence of the liquidity, the monetary policy becomes ineffective. In his argument, the liquidity preference is a reaction against risk. The more the risk that is involved in the purchase of government bonds, the more people who are willing to hold their assets in the form of cash balances as argued before. This situation occurs when the prices of the bonds are high and or are expected to fall in the near future. Individuals and firms will not purchase these bonds for fear of incurring losses. Hence, they will then choose to hold all their assets in the form of liquid cash. The less the risk that is involved in the purchase of government bonds, the less the people who will be willing to hold their assets in the form of cash balances. They will choose to purchase the bonds in anticipation of making super normal profits when the prices shoot when they will sell them back to the government. Lee (2000) adds that, Keynes theory is also applicable at the government and national level as well because the demand for cash balance is perfectly inelastic to interest rate thus implying that the assumption that demands for cash balances is interest inelastic is then incorrect.

At the aggregate level, as mentioned earlier, the liquidity trap renders the monetary policy ineffective. Monetary policy here refers to the actions taken by the central bank of a country to control the money supply in the economy. These actions include an increase in interest that is charged to loans given to commercial banks by the central bank. According to Samuels, Biddle, and Emmett (2008), this increment leads to an increase in the interest rates thus affecting the rate of investment in the economy. At times, the government opts to be involved in OMO (open market operation), which refers to selling and buying of government bonds. In a case where there is a lot of money circulating in the economy, the government lowers the prices of the bonds thus selling more of them. Keynes argues that part of idiosyncrasy of money happens from the certainty that it has a very tiny elasticity of invention meaning that the answer got from the magnitude of effort applied to constructing it to an increase for work, which a component of it will dominate, is miniscule. People purchase these bonds speculating to sell them at a higher price in the future at an anticipated profit. In the case where there is too little money circulating in the economy, the government opts to buy the bonds from the people.

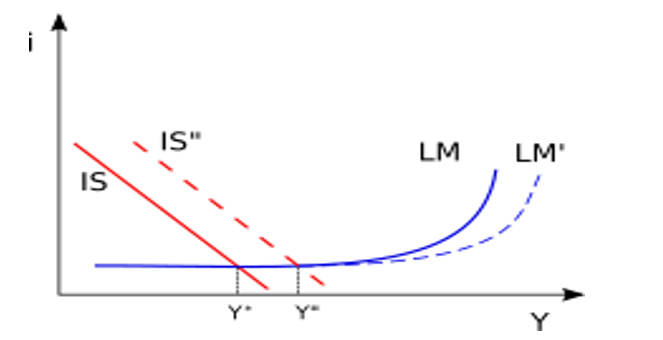

The point where the interest rates become so low that people opt to store their money for speculative purposes is the liquidity trap. According Defermos (2012, p. 755), “Liquidity trap visualized in a IS-LM diagram. A monetary expansion (the shift from LM to LM’) has no effect on equilibrium interest rates or output. However, fiscal expansion (the shift from IS to IS”) leads to a higher level of output with no change in interest rates: Since interest rates are unchanged, there is no crowding out”

It renders the monetary policy ineffective when the fiscal policies are used. Fiscal policies are government policies that affect revenue collection through taxation and interest rates. According to Lee (2000), because the liquidity trap is the point where there is a high level of inflation with too much money chasing after too little goods, fiscal policy comes in to aid in deflation. Contemporary studies have shown that, not only are the developing countries the only ones that are dealing with inflation but also the developed countries such as the USA and countries in the EURO zone. Lee (2000) adds that, in times of inflation, most countries opt to state that they will not borrow because additional borrowing will add heavily to the future debt, which will be an unreasonable burden on the future generations. At this point, a generation happens to be paying a debt taken and consumed by the previous generations. In fact, “holding more of it allows borrowers to counterbalance this possibility and prevent a distress selling of their assets” (Defermos, 2012, p. 755). This realization will be good returns for those who will be caught up in the sale of these bonds. However, in the liquidity trap, none of the above arguments has proved to work in favor of the situations because of the following reasons. Firstly, Japan’s experience of more than 20 years of its recent past has proved that governments operating with a floating currency do not experience any constraint in borrowing. The reason here is that the private sector does not want to borrow as a strategy of reducing its debt. Secondly, there is no crowding.

Most of the developed countries like the UK, the USA, and Australia have found out, “the importance of fiscal expansion and the significance of monetary policies in a liquidity trap situation because they have profound the effects of the conduct of the central banks of these countries” (Hunt & Lautzenheiser, 2011). In a liquidity trap, the risk of inflation is replaced by the risk of deflating. In this situation, Hunt and Lautzenheiser (2011) put it out that there is no need for independent central banks to offset since, by so doing, they end up punishing fiscally irresponsible governments. Instead, central banks finance and go ahead to encourage economically responsible governments. When the private sector’s credit growth is restricted, monetarization of public debt is not inflationary. It would rather be better if it were inflationary since that would essentially ensure a stronger recovery, which would demand effective and efficient reversal of the policy mix. Nevertheless, since it is not an inflationary factor, it means having a mix of both two policies working against the economy of a country. In essence, aggressive fiscal policies do not work in the unusual situations of a liquidity trap specifically if combined with monetarization. However, conventional knowledge restricts complete implementation of the unorthodox tool kit. Historically, as suggested by Hunt and Lautzenheiser (2011), it is evident that political pressure has destroyed such resistance. Political pressure made the UK leave gold in 1931. Heilbroner (1999) refers this case a “tangible pressure of the environment” (p.19). Nevertheless, it is also believed to have given power to the dictatorial governance of Adolf Hitler in Germany in 1933. This case means that the Euro zone should take note in the event of a liquidity trap. Magnified fiscal deficits have high chances of reducing the future levels of privately held public debt rather than increasing them and hence the core assumption of most of the developed countries.

Conclusion: Drawback of the Keynes’ Theory

In conclusion, as much as Keynes’ theory of demand for money is applicable in people’s daily lives, it has the following drawbacks that make it not to be completely applicable. It assumes that people hold their assets in either money or bonds. The argument is very much unrealistic as most individuals hold their assets/wealth in some combination of both money and bonds. They hold a portfolio of both. The theory asserts that one cannot hold a combination of both meaning that the individual is either given a chance to take a complete risk of all his or her assets by investing in the government bonds or have absolutely no risk by having all his or her assets in the form of cash balances. The individual is not given the chance to have some amount of his assets as being risky and while others are riskless. The theory is also under the assumption that one cannot hold the same unit of money for more than one motive. This assumption is not true as one unit of money can be held to serve many motives depending on which one comes first. Money cannot be divided into two or more departments independent of each other. Most individuals hold the same amount of money that can be used for expenditure. It can also be used in case some unforeseen events such as diseases or accidents come up. In case the same unit of money is not used for those two purposes, it can be used for speculative purposes when the market presents a chance to invest and earn interest income. In this view, Keynes’ money demand has been modified and can be represented in the following equation where it is an increasing function of income and a decreasing function of interest rates i.e. MD = L (Y, r). The other drawback is that the theory asserts that the M1, which is the transaction demand for money plus the precautionary demand for money, is unresponsive to interest rates.

Reference List

Defermos, Y. (2012). Liquidity preference, uncertainty, and recession in a stock-flow Consistent model. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 34(4), 749-776. Web.

Heilbroner, R. (1999). The worldly philosophers. (7th ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster.

Hunt, K., & Lautzenheiser, M. (2011). History of economic thought: A critical Perspective. Armonk, N.Y: M.E. Sharpe.

Keynes, M. (1932). The World’s Economic Outlook. London: Routledge.

Lee, S. (2000). The organizational history of Post Keynesian economics in America,

1971-1995. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 23(1), 141-62. Web.

Samuels, J., Biddle, J., & Emmett, B. (2008). Research in the history of economic thought and methodology: A research annual. Bingley: Emerald/JAI Press.