Summary

The tomb of the young pharaoh Tutankhamun is one of the most significant archaeological finds in the exploration of Ancient Egypt. It is located in the Valley of the Kings and was discovered in 1922 by Howard Carter. This tomb is referred to as KV62 in standard Egyptological designation. Compared to other royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings, Tut’s tomb is less richly decorated and contains fewer artifacts (Sambuelli et al. 1).

Additionally, some objects, including the sarcophagus and shrine, were likely created for the burial of another deceased but were hastily used for Tutankhamun. This fact is associated with the pharaoh’s early and probably sudden death, which required the builders and decorators to arrange the tomb quickly. The most valuable aspect of the tomb is the wall paintings that reflect the religious views of the Egyptians, as well as explain burial rituals and beliefs about the Afterlife. The tomb of Tutankhamun also displays many artifacts that have ritual significance. The most notable of these is the golden mask and quartz sarcophagus containing the pharaoh’s coffins and mummies.

The Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings is located on the east coast of the Nile near the city of Luxor. It is the largest collection of royal and elite tombs of the Ancient Egyptians, created during the New Kingdom (1500-1100 BC) (Handwerk para. 2). The particularly dry conditions of this location were perfect for preserving the mummified remains. The Valley of the Kings is the burial place of the most famous pharaohs, including Seti I, Ramses II, and Tutankhamen, as well as the queens, priests, and elites of the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties (Handwerk para. 3). Wilkinson notes that in later periods (950–850 BC), many prominent tombs were afterward reused by other elites (12-34). The tombs in the Valley of the Kings also developed underground parts.

The Valley of the Kings is full of artifacts, making it an attractive destination for archaeologists and robbers. Even though as early as 1912, researchers considered it to be fully exhausted, Howard Carter, in 1922, discovered the most significant and fascinating tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun (Wilkinson 30-36). This discovery was the last tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Since then, archeologists have been exclusively describing and documenting this location’s already-known artifacts and monuments.

The Coffin Description

Before proceeding to the description of the coffins of Tutankhamun, it is necessary to pay attention to the sarcophagus, which is a unique example of the funeral traditions of the New Kingdom. The sarcophagus is made of brown quartzite and pink granite, but the combination of these materials was rather forced due to the limited time or materials available (Farrant). On the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun, one can see the figures of four goddesses, including Isis, Nephthys, Neith, and Selket. These goddesses in Ancient Egyptian mythology were revered as protectors of the dead. The figures are located along the edges of the sarcophagus with spread wings, symbolizing the divine protection of what is inside (Farrant). Eaton-Krauss notes that these figures initially had only outstretched arms with no wings, and the text on the sarcophagus itself was erased and recarved (Shaw 56-58). These changes probably indicate that the sarcophagus, like some other burial attributes, is another adoption from Smenkhkare/Neferneferuaten’s burial outfit (Farrant; Shaw 56-58). Smenkhkare/Neferneferuaten are the pharaohs who probably ruled in the second half of the 18th Dynasty period and whose burial outfit was used for Tutankhamun. This fact, in turn, may be associated with the need to rush to the burial due to the untimely death of Pharaoh Tutankhamun.

However, the rectangular quartzite sarcophagus is only an outer layer. Inside it is three coffins that depict Tutankhamun in the position of the god Osiris (Marie para. 6). The inner coffin in which the mummy was located was wrapped in linen except for the head. It is made of pure gold weighing over 110 kilograms and repeats the shape of Tutankhamun’s mummy (Marie para. 7). The middle and outer coffins are made of wood and covered with a thin layer of gold and plaster. The middle coffin is also covered with polychrome glass pastes, while the outer one is equipped with silver handles for the movement of the lid (Marie para. 9). The figure of Osiris holds a crook and flail crossed on his chest, inlaid with gold, as well as pieces of red and blue glass (Wilkinson 112-118). The coffins are located one inside the other, and all of them, in turn, is inside the sarcophagus. Inside the inner coffin was Tutankhamun’s linen-wrapped mummy.

The Structure of the Tomb

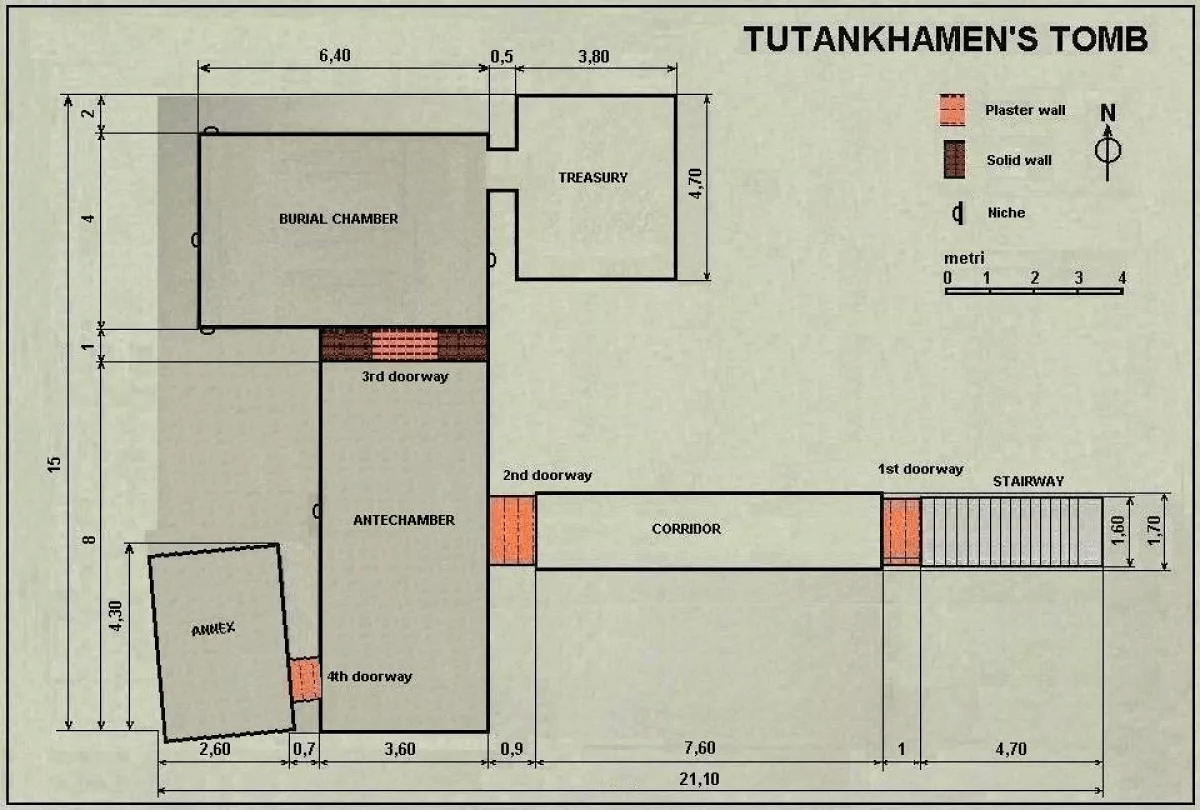

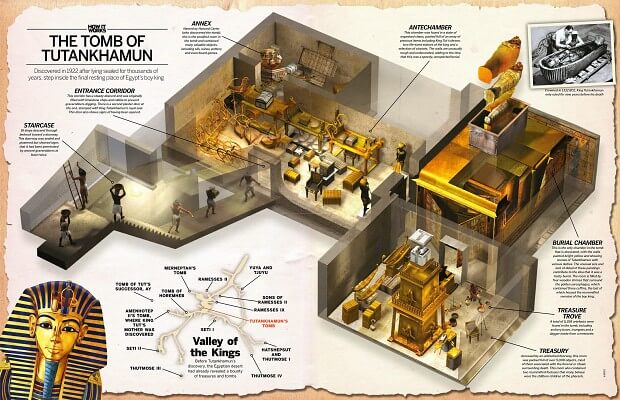

The structure of Tutankhamun’s tomb is fairly well studied and contains several rooms. It includes “four main rooms; the antechamber, the annex, the burial chamber, and the treasury room” (“King Tut’s Tomb Layout” para. 1; fig. 1). It is noteworthy that this tomb, upon discovery, was not plundered, which is rare for the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Despite the fact that the tomb contains almost 5,000 objects, the tomb of Tutankhamun is smaller in size than the rest of the royal tombs found, as he ruled for a limited time and did not leave an extensive legacy (“King Tut’s Tomb Layout” para. 3). The passage to the tomb is made of limestone, and the steps go down into the Valley of the Kings. At the end of the passage is a plaster wall depicting a jackal and nine slaves, symbolizing the royal power of Tutankhamun (“King Tut’s Tomb: Entrance Passage” para. 1). Behind it is another plaster door with the seals of Tutankhamun and numerous priests.

The antechamber is located immediately after the passage and is a connecting element from which one can get to other rooms. Again, compared to the tombs of other pharaohs, this room was more modestly decorated but contained about 700 objects “such as couches, chests, baskets, large statues, beds, and stools” (“King Tut’s Tomb: Antechamber” para. 3). From the antechamber, you can get to the burial chamber with the adjoining treasury, as well as to the annex (fig. 2). The annex is the smallest of the chambers in the tomb and contains various objects as well (“King Tut’s Tomb: Annex” para. 1). It is noteworthy that the door to this room is cut on the left side of the antechamber and is located between the legs of the couches. Additionally, the floor level in this chamber drops three feet relative to the other rooms (“King Tut’s Tomb: Annex” para. 2). Among them were items “such as oils, foods, wines, pottery, dishes, stools, games, and baskets” (“King Tut’s Tomb: Annex” para. 1). This room contained 280 objects in total that were located in disarray.

The Paintings Description and Meaning

Besides treasures and many objects, Tutankhamun’s tomb contains unique wall paintings located on each of the walls. Due to the early death of Tutankhamun, the drawings are located only in his burial chamber (Alchin para. 2). Each of the four walls displays different themes and plots, including the Funeral Procession, the Amduat, the arrival in the Underworld, and the arrival of Tutankhamun in the Afterlife (Nyord 1-8). Thus, the drawings reflect the religious ideas of the Ancient Egyptians about the Afterlife and the rituals associated with this concept.

The background of all the walls and paintings in the burial chamber is gold, which is associated with the rule of Pharaoh Tutankhamun. All the figures of people depicted on the walls are young, which shows the tendency of the Ancient Egyptians to idealize people in art (Alchin para. 3). Despite the actual heights of Tutankhamun, his figure was portrayed as the largest and stood out from the rest of the paintings (Cleveland-Peck 85-94). The Egyptians used six primary colors for their tombs, including “white, black, red, yellow, blue and green” (Alchin para. 4). Each color had a symbolic meaning and emphasized the distinctive characteristics of each of the represented figures.

The eastern wall of the burial chamber depicts the funeral procession of Tutankhamun. First of all, there is an image of Tutankhamun’s mummy on a sleigh pulled by 12 people (Alchin para. 5). These figures symbolize the people closest to the Pharaoh. They are depicted wearing white sandals and bands, which identifies them as priests (white is also the color of purity and greatness, a sacred color). 12 people are represented by one group of 5 people, three groups of 2 people, as well as a lonely freestanding figure. Some of them can be identified by the elements of clothing: the hereditary Tutankhamun depicted in the crown, the two viziers, the chief treasurer, the General Horemheb, as well as the High Priests.

The western wall of the tomb describes the path of Tutankhamun to the Afterlife, described in the text of the funerary book, which is called Amduat. This book “is the Book of the Secret Chamber and means’ That Which Is in the Underworld” (Alchin para. 6). In particular, this text describes the journey of the Sun God through 12 parts of the Underworld from west to east. This path must be safe for Tutankhamun to enter the Afterlife successfully. The 12 parts of the Underworld meet the 12 divisions of the book and represent 12 night hours (Alchin para. 6). Additionally, they are also symbolized by the 12 baboons also depicted on the wall. There is also a depiction of the Solar Barque and Tutankhamun as Osiris on the wall. This plot illustrates the Egyptians’ ideas about the Pharaoh’s transition to the Afterlife through the Underworld and the return to divine form.

The south wall illustrates Tut’s arrival in the Underworld, where he is greeted by Hathor, Anubis, and Isis. NetBet is the incarnation of Hathor, who is the patroness of Upper Egypt and also the protector of the pharaoh along with Wadjet (Alchin para. 7). Thus, the southern wall depicts the successful arrival of the pharaoh in the Afterlife under the auspices of the gods and his transition to the Afterlife. The North wall contains three separate scenes depicting the immediate arrival in the Afterlife. Tut’s heir, Ay, performs the opening of the mouth ritual in front of Tut’s mummies. He is dressed in the robe of a priest with leopard skin (Alchin para. 8). Next, the Heavenly Goddess Nut welcomes Tutankhamun to the Afterlife and accepts him among the gods.

Most notable are the three separate depictions of Tutankhamun, representing the Egyptians’ perception of the essence of the pharaoh. On the first, he is represented as Horus, the son of the god Osiris and wears a double crown (earthly incarnation); as the god Osiris (true essence in the Afterlife); and the image of Tutankhamun’s Ka (Alchin para. 8). Thus, the northern wall most thoroughly depicts the Egyptians’ ideas about the Afterlife and the Pharaoh’s transition into it. Moreover, in general, the paintings in Tutankhamun’s tomb illustrate royal funeral rites as well as religious beliefs. The texts on the walls are associated with the Book of the Dead, which describes rituals for burying the dead for their successful entry into the Afterlife. As can be seen from the paintings, in the Afterlife, the Pharaoh takes on his true god form and takes his place among the other gods.

The Religion Text and the Book of the Death

The religious texts of the Egyptians were intended to protect the dead on their journey to the Afterlife. Most importantly, these texts prescribe specific funeral rituals to be followed. The Book of the Dead is a set of rules that are reflected in spells created to protect the mummies and the spirit of the departed. These spells were engraved on various material objects to provide protection. In particular, Tutankhamun’s mask and coffin contain the spell ahead of mystery (Lucarelli 137-140). This text concerns the position of the golden mummy mask and reflects the myth of how Ryo bestowed the mask on Osiris to heal his injuries. Moreover, extracts from the Book of the Dead are also on the golden chapels of Tutankhamun located above his coffin (Cleveland-Peck 85-94; Lucarelli 137-140). Spell texts could be engraved on any tomb artifacts and reflect this object’s purpose in the Afterlife. In general, the Book of the Dead described how funeral rituals should be performed.

The Description of the Artifacts

Tutankhamun’s tomb contains many artifacts that reflect the Egyptians’ views of the Afterlife. The most notable of these is the golden mask that was placed on the head of the pharaoh’s mummy. It was found directly in the inner coffin and is made in the form of the face of Tutankhamun. This artifact was intended to protect the face of the deceased during his journey to the Underworld and is associated with Egyptian mythology (Lucarelli 137-140). The artifacts in the antechamber are mostly furniture and everyday objects that were designed to provide the pharaoh’s comfort in the Afterlife. Most notable are the couches containing a “hippopotamus, a lion, and a cow’s head” (“King Tut’s Tomb: Antechamber” para. 4). They are made of wood and gilded and most likely were used for ritual purposes. Additionally, this room contains the throne of Tutankhamun and three chariots. The entrance to the burial chamber is guarded by two large statues of the pharaoh, facing each other and containing inscriptions.

The annex also contained various artifacts that reflected aspects of the pharaoh’s life. The most notable are the games, which underscore the early age of Tutankhamun’s demise (“King Tut’s Tomb: Annex” para. 2). In addition, food, coins, and oils were contained in the annex. The treasury contained the largest number of ritual objects that illustrate the funeral rites of the Egyptians. In particular, the most important artifact is the canopic jars, containing the pharaoh’s organs extracted before mummification (“King Tut’s Tomb: Treasury Room” para. 2; fig. 2). The banks were located on a gilded wooden shrine with images of goddesses who protected the organs of the pharaoh. The jars are made of alabaster and have the shape of a pharaoh’s head with clearly traced facial features.

The room also contained numerous small figurines of the pharaoh and gods, also made of wood with gilding. The statues depict different aspects of the life of the pharaoh, and 34 of them were discovered (“King Tut’s Tomb: Treasury Room” para. 3). The treasury also contained 14 boats that had ritual significance and were intended for the pharaoh’s movements in the Afterlife (“King Tut’s Tomb: Treasury Room” para. 4). It is noteworthy that all are located pointing to the west. Thus, the artifacts presented in the tomb of the pharaoh reflect both aspects of everyday life and are of a ritual nature. They were all placed there to accompany Tutankhamun in the Afterlife and to provide protection for his mummified body and organs.

The Burial Chamber and Treasury

The burial chamber is the largest room in the tomb, which contains a sarcophagus, and its walls are completely covered with paintings. Again, the paintings in Tutankhamun’s tomb are large enough compared to other tombs in the Valley of the Kings, which identifies a possible rush to create them (“King Tut’s Tomb: Burial Chamber” para. 1). Fraser et al. note that an enormous wooden shrine nearly entirely occupied the burial chamber (127). Inside there were three more wooden shrines covered in gold that protected the sarcophagus. The exterior parts of the shrine are decorated with amulets of Osiris, and the fourth shrine depicts the eyes of Wadjet (Cleveland-Peck 85-94). It is noteworthy that the markings on the shrine also identify that they were created for a different tomb (Egypt Museum). Outside the shrines, the burial chamber also contains numerous paddles for a solar boat, vessels for wine and incense, and lamps depicting the god Hapi.

The treasury adjoins the burial chamber, and its entrance is located on the east wall. At the entrance to the treasury, there is “a statue guard with a large portable shrine of the jackal-headed god named Anubis” (“King Tut’s Tomb: Treasury Room” para. 1). This room contained chests, shrines, chests, boats, and presumably two stillborn daughters of Tutankhamun (“King Tut’s Tomb: Treasury Room” para. 1). All of these items are necessary for Pharaoh in the Afterlife, which also illustrates the religious views of the Egyptians. The largest items in this chamber are the Pharaoh’s canopic chest and the statue of Anubis. Additionally, the room contained many statues of the king and deities, boats, and chariots. All items in the treasury were of a ritual nature and served as an illustration of the Egyptians’ ideas about the Afterlife. In particular, they considered all of this necessary for a successful transition to the Afterlife. Each item either illustrates the protection of the gods or is necessary for the pharaoh when traveling to the Afterlife through the Underworld.

Works Cited

Alchin, Linda. “Tutankhamun Tomb Paintings.” History Embalmed, Web.

Cleveland-Peck, Patricia. The Story of Tutankhamun. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Egypt Museum. “Innermost Gold Coffin of Tutankhamun.” Egypt Museum, Web.

Farrant, Theo. “100 Years on from the Discovery of King Tutankhamun’s Tomb.” Euronews, Web.

Fraser, James, et al. Speak My Name. Sydney University Press, 2022.

Handwerk, Brian. “Valley of the Kings.” National Geographic. Web.

Journey to Egypt. “Valley of the Kings.” Journey to Egypt, Web.

“King Tut’s Tomb: Treasury Room.” Ancient Egypt Online, 2021, Web.

Lucarelli, Rita. “The Materiality of the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead.” Maarav, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2019, pp. 137–50, Web.

Marie, Mustafa. “Acquaint Yourself with Tutankhamun’s Multi-Layered Sarcophagi.” EgyptToday, Web.

Nyord, Rune. “Seeing Perfection: Ancient Egyptian Images beyond Representation.” Elements in Ancient Egypt in Context, Web.

Sambuelli, Luigi, et al. “The Third KV62 Radar Scan: Searching for Hidden Chambers Adjacent to Tutankhamun’s Tomb.” Journal of Cultural Heritage, vol. 39, 2019, pp. 288-296.

Shaw, Garry J. The Story of Tutankhamun. Yale University Press, 2023.

Wilkinson, Toby. Tutankhamun’s Trumpet: Ancient Egypt in 100 Objects from the Boy-King’s Tomb. W. W. Norton & Company, 2022.