- Modern Implications of Health Care Leadership

- Leader or Administrator: Opposition or Convergence? Middle East Context

- Distributed Leadership in Healthcare

- Leadership Competencies for Healthcare

- Healthcare Leaders’ Skills in Change Management

- Leadership under the Conditions of Turbulence in Healthcare

- Works Cited

Modern Implications of Health Care Leadership

In modern high-tech healthcare, human resources have a heterogeneous structure. They cover a wide range of specialists ‑ doctors, medical workers (nurses, midwives, rehabilitologists, laboratory assistants, etc.), psychologists, social workers, programmers, lawyers, teachers, economists, etc. To achieve effective human resources management when working with personnel in the health care organization, leaders and managers must implement a broad team approach. If the members of a team join forces and focus on expressing their real potential, minimizing shortcomings, the team’s goals will be successfully achieved. The consolidation and integrity of individual team members are key to the success of the organization. Often medical organizations with fewer employees achieve better results than those with a large number of medical specialists.

The experts developed guidelines for organizing teamwork in the healthcare sector. They focus on the fact that strong leadership can help solve problems in the process of reforming national health systems. It is noted that it is important to involve all interacting entities and subjects in the work to ensure the necessary integration. According to the above recommendations, successful leadership in the process of improving healthcare combines three sets of skills (Fitzgerald et al. 227-239):

- “Specific knowledge” (service-specific knowledge) ‑ an understanding of how clinical services work and what is required to provide high-quality services;

- “Improvement knowhow” ‑ improvement skills in the health sector, covering techniques adapted from the industry, such as lean manufacturing, Six Sigma, TQM, etc., as well as clinical methods such as clinical audits and studies;

- “Change management skills” ‑ skills that include conflict resolution, building support coalitions, overcoming resistance to change, transmitting the vision to staff, patients, the public, and stakeholders.

It may be noted that the assessment of effectiveness from the point of view of various interacting entities is significantly different (it is about budget, social, medical effectiveness, etc.). Bearing in mind the activity and nature of managerial work and the functions of a leader, as well as the variety of personal qualities that a manager should have, such as, for example, insight, ambitiousness, self-confidence, communication skills, responsiveness, adaptability, it becomes clear that this should to be a kind of an ideal person, combining all these qualities. That is why it is necessary to form an effective management team, demonstrating good leadership skills, which will become a tool for the guaranteed success of a medical organization. Nevertheless, the observations and studies of the leaders of medical institutions in different countries, for example, with the use of Belbin test, showed a very low level (4%) of people with skills of leadership, which means that the role of a leader is replaced by administration and this is a serious obstacle to effective management (Barr 113-123). It is time for the administrator’s halo to give way to the realistic image of the new health care manager.

Meanwhile, the administrator has strictly fixed professional training background, pursues mainly short-term goals, is limited in communications, being a ‘fan’ of tradition, uses mostly ready-made recipes and solutions “from above,” with poorly developed and unused imagination, with no sense of humor. The manager-leader is strategically oriented, pursuing long-term goals, communicative, flexible, creative, breaking stereotypes, focused on finding innovative solutions, active, successfully coping in unusual situations, with a highly developed imagination and sense of humor. The leader’s style reflects his characteristic behavior, approach and attitude towards subordinates in decision making and the exercise of power. The bipolar model of management or leadership style is traditionally considered ‑ authoritarian and democratic, but it is important to know that there are intermediate nuances among them.

In general, the effectiveness of a leader depends on the needs of solving common problems, the individual needs of team members and the need to support the group. The choice of the medical profession is the result of humane motives and beliefs, but this is not enough for effective personnel management in a medical organization. Effective management requires the manager at any time to know not only what and how people work, but also what meaning they put into their work and what satisfaction they get from it.

Leader or Administrator: Opposition or Convergence? Middle East Context

One should treat with great respect and understanding the role and efforts of those health managers who seek to cope with the difficult task of effectively managing the professionals involved in their structures and organizations. This is because being a manager and simultaneously a real, not only formal, leader is not an easy task, but for many people this is the job they dream of. In the minds of those who are not familiar with the profession, being a manager means commanding and receiving a lot of money, but the important question is whether this is really so? In fact, this is a kind of challenge to the professional and personal qualities of a leader. This activity requires managerial competence, which does not only mean special knowledge in a specific professional field, but also skills in the field of strategic thinking; ability to communicate with people at different levels; ability to lead people and motivate them; gather a team of professional employees united by one goal, ready to make the necessary changes in accordance with the requirements of the time; negotiation skills, etc. (Dye 42). Thus, the ability of a manager to combine management with leadership is important. Such knowledge, skills, and behavior are primarily achieved through education and gaining experience, because leadership, in accordance with the thesis of Adair, is both a quality and a role that can be learned (35). Thus, management (control) and leadership represent subsystems of one system.

In one study, based on a survey conducted among 220 healthcare managers and 730 hospital medical workers, a number of key management competencies were clarified and a model was drawn up for developing leadership competencies in the healthcare field, in accordance with general standards for the use of data obtained on the basis of best practices that determine the requirements for competent performance of work and the necessary personal qualities in accordance with the specifics of healthcare and its management (McLaughlin 17). It provides a general framework for modeling the key managerial skills needed to optimize managerial training for the effective management of human resources in a healthcare organization. At the same time, personal qualities, self-reflection and mental stability represent the basis of managerial competencies.

However, this does not mean that some cannot learn the rules and principles of good management, while others cannot lead teams. In addition, in everyday life, it is always necessary. This is because both sides of the leader are inseparable, and which of the two will be more visible and look more important depends on the personality structure, the nature of the organization and the specifics of the situation. As Ts. Vodenicharov, one of the leading Bulgarian strategists in healthcare management, notes, “Efficiency is the key to a successful business because it develops in a competitive environment… The main tool is information, and the main condition is the psyche. We must shape the mind of the winner…” (qtd. in McLaughlin 21).

The question of what makes a person a leader has long been of interest to specialists in the field of management and social psychology. One of the most famous answers to this question is given by the theory of great people, which claims that if a person has a certain set of key personality traits, then he will be a good leader, regardless of the nature of the situation in which he is. If this theory is true, then one must identify the key aspects of the personality that make a person a great leader. Will it be a combination of mind, charisma, and courage? Which is better: to be an extrovert or an introvert? Should we add a little ruthlessness to this mixture, as N. Machiavelli suggested? Or, maybe, high-moral people are the best leaders?

Some fairly weak relationships between personality traits and leadership do exist. For example, leaders usually have a slightly higher intelligence than non-leaders, are driven by a stronger desire for power; they are more charismatic, better socially prepared, and more flexible and adaptive. However, in general, it can be said that strong relationships between personality traits and success of leadership practice do not exist. Not surprisingly, it turned out that only a small number of personality characteristics are related to the effectiveness of leadership, and even existing relationships are usually quite weak. Too often, in management practice, the so-called fundamental attribution error is made when the causes of a person’s behavior are sought in his personality traits, neglecting the influence of the situation (Leggat 36). However, namely the situation is more important for understanding human behavior than personality traits. Thus, to understand the leader’s behavior and the mechanism for making managerial decisions, it is necessary to take into account not only his personal characteristics, but also the social situation in which he is. In other words, we must consider both the human’s personality and the situation in which he has to play the role of leader. According to this point of view, in order to become a leader, it is not enough to be a “great man,” but one needs to be the ‘right person at the right time’ and in the right situation. For example, the head physician of a medical institution can act very successfully in some situations and fail in others.

It is known that some leaders are better at routine daily work, while others act better in extreme situations. Thus, the effectiveness of leadership style depends on the situation, psychological characteristics, training and motivation of subordinates, and is situational in nature (Arroliga et al. 84). That is why the problems of leadership and its effectiveness are currently being considered from three interrelated positions presented in Table 1 (LeGrand 86).

Table 1: The main approaches to solving problems of leadership and leadership effectiveness

It should be remembered that ‘production’ tasks can be divided into unitary, separable, additive, conjunctive, and disjunctive (Table 2) (Hanaway 64). Naturally, the leadership style in the implementation of each of them must correspond to the task at hand.

Table 2: Types of tasks solved

Currently, there are several theories of leadership that focus simultaneously on the personal properties of the leader, on the characteristics of his environment and followers, as well as the situation in which the leader acts. The most famous of the theories of this kind is Fred Fiedler’s situational theory of leadership, which states that the effectiveness of a leader depends on the extent to which the leader is task-oriented or is oriented on relationships, and on the extent to which the leader controls the group and exercises his influence on it. Thus, leaders can be divided into two types: 1) task-oriented and 2) relationship-oriented (Arroliga et al. 100-102). A task-oriented leader is more concerned with the work being done properly than with the relationships between employees and their feelings. A relationship-oriented leader is primarily interested in what feelings and relationships arise among employees.

The cornerstone of Fiedler’s situational theory is the assertion that neither of these two types is more effective than the other in all circumstances. It all depends on the nature of the situation, namely, what is the degree of control of the leader and his influence among the members of the group. In a situation of “high control,” the leader builds strong relationships of the interpersonal nature with subordinates, and his position is clearly considered by followers in the group as quite influential and dominant, and the group’ work is well structured and clearly defined. In the situation of “low control,” the opposite phenomenon takes place ‑ the leader has a bad relationship with his subordinates, and the work that the group should do is unclear.

According to experts in the field of group dynamics and management, task-oriented leaders are most effective in situations with either a very high or a very low level of control (Bolden 72). In cases of “high control,” people are happy, everything goes smoothly and there is no need to worry about the feelings of subordinates or their relationships. Here the leader, paying attention only to the completion of the task, achieves the best results. When the control of the situation is low, the task-oriented leader is better able to organize the situation and bring at least some order into the confused and uncertain working environment. By focusing on the work, the leader can do a lot to increase productivity and labor efficiency, while he is not able to change the human nature and prevailing human relations in a short period. However, in situations of medium degree of control, the most effective are relationship-oriented leaders. In this case, everything goes smoothly, but still it is necessary to pay some attention to the problems arising from human feelings and poor relationships in the group. A manager who is able to smooth out these roughnesses acts most effectively in such a situation. Thus, according to Fiedler’s theory, task-oriented leaders achieve the best results when the control of the situation is very high or very low, while relationship-oriented leaders are most successful in situations of moderate control (McLaughlin 15).

It should be borne in mind that the effectiveness of a leader and the very ability to be a leader are different concepts and are evaluated according to different criteria. An outstanding leader can be a poor manager and lead his followers in an unknown ‘place’ with the most deplorable results. Such examples, both among historical figures and among ordinary leaders of various organizations, are more than enough. At the same time, modest leaders with even slightly pronounced leadership traits can achieve significant results in their field of activity. Of course, one should not confuse the effectiveness of the leader with his abilities to occupy and hold the office. These are different competencies, although there are still cases when people are nominated and appointed to senior positions in accordance with their professional educational background and work experience.

From the works of Nick Bloom, Rafaella Sadun and John Van Reenen, it is clear to what extent good managerial practices are important for the effectiveness of the hospital. Also, these researchers found that the most significant positive effect is an increase in the share of managers with medical education (qtd. in Alloubani 26). In other words, the separation between medical and managerial competencies in hospitals is associated with poor management.

The idea that healthcare organizations should be managed by physicians is consistent with observations from many other industries. Specialists in different fields (the same expert leaders as doctors in medical institutions) are in one way or another connected with more effective management of organizations in such different areas as university education (where scientific leaders improve the quality of research), basketball (i.e., the trainers, when those who played for the team of all stars achieve success in the NBA), and the Formula 1 race (where former racers become excellent team leaders).

For example, American Mayo Clinic’s website claims to be managed by a doctor, because “it helps ensure a constant focus on the core value ‑ the patient’s needs” (Berry and Seltman 145). Because doctors take into account the interests of patients throughout their career path when they come to leadership positions, this is expected to bring a more patient-centered strategy (Berry and Seltman 146). In a recent study, where managers and subordinates were compared using random sampling, it was found that the leader with expertise in the core business is associated with a higher level of employee satisfaction and there is a small number of people who want to quit; this also applies to medical leaders (Vender 362-365). Perhaps they know how to increase the satisfaction of other doctors, thereby increasing the effectiveness of the entire organization.

However, the Arabic management style is greatly influenced by the religious traditions of Islam, family and friendly relations, and community interests. For a more complete presentation of the driving forces of the Islamic style of business management, the Islamic business concept should be considered. First of all, it should be noted that this concept is based on ethics. In Arabic, the concept of ethics is expressed as “ahlak,” which means “motivation of behavior” (McLaughlin 110). The concept of motivation, as it is known, includes intrinsic intention, will and determination, and behavior is a way of life and human action; obviously, motivation underlies behavior. That is why Muslim dogma is aimed at developing incentives for pious acts and a righteous lifestyle.

Let us consider some important characteristics of the Arab system of leadership, management, and motivation. The system of labor motivation is based on the desire to obtain new authoritative powers. The quality control system is based on social responsibility, in particular, on religious norms. The hierarchy of control is of the vertical type, and a rigid management structure is one of the most frequent organizational characteristics. The mobility of the control system is reduced due to the combination of a rigid hierarchy with an underestimation of the importance of a time resource (there is no awareness of the significance of the time limitations of all processes, including communicative ones), and, therefore, the speed of decision-making is small, which makes decisions implementation difficult. In healthcare organizations, this can be a critical influence factor.

At the same time, in the Middle East and North Africa, noncommunicable diseases such as heart disease (an increase of 44%), stroke (an increase of 35%), and diabetes (an increase of 87%) cause an unprecedented number of cases of premature death and disability (El-Saharty 14-15). Potentially manageable risk factors such as an unhealthy diet, high blood pressure, obesity and overweight, as well as smoking all contribute to the growing burden of noncommunicable diseases in the region. However, there is an evident lack of relevant programs for raising public awareness.

Moreover, the significant progress made by the Arab countries of the Middle East and North Africa over the past decades has reversed due to political unrest and civil wars that have swept the region. This reversal is especially noticeable in the health systems of Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen, which were previously steadily improving. Until 2010, in these countries, there was an increase in life expectancy, a decrease in the size of damage from infectious diseases, as well as decrease in the level of infant and maternal mortality. However, disruptions in health systems today exacerbate the suffering and calamities caused by the many conflicts in the region. These are the findings of a recent study by the authors of The Lancet magazine. It analyzes the data of the Global Burden of Disease 2013 report to identify the effects of deterioration in the health systems of the Eastern Mediterranean countries (Mokdad et al. e704-e706). At the same time, not a single region has changed in such a radical way as the Arab world, and these transformations are continuing.

Of course, the level of economic development and the country’s financial capabilities determine the nature and trends in the development of the healthcare sector. Studies show that Kuwait, Qatar, and the UAE are the best countries in the region in terms of creating a healthcare system that can respond quickly in different circumstances. According to WHO experts, they rank from 26th to 30th place in the world in terms of healthcare among 191 countries covered by the sample (Babar 237, 405). It is interesting to note that in the UAE, in the “pre-oil era,” medical care came exclusively from abroad. The first hospital appeared there, according to some sources, in the 40s of the last century and was designed for 38 beds with a single doctor ‑ a retired colonel of the English army. With the active assistance of the United States, three hospitals of the American Mission in Sharjah, Abu Dhabi, and Ras al-Khaimah were built in the 50-60s of the 20th century. The entire staff consisted of Americans and Canadians (Koornneef et al. 116). Accordingly, this also determined the vector of development of leadership patterns in medical staff behavior.

Of course, current events are changing the situation in the field of public health, but this effect will fully manifest itself only after years. Popular protests helped to reveal crucial social issues, among which there are unemployment, poor social and health services, exclusion. These are the main social determinants of health that public healthcare should deal with. There is a huge task ‑ to rebuild the institutions of the health system, for example, in Libya. For the first time in decades, new democratically elected governments will have to live up to the expectations of voters in all sectors, and public health is no exception.

The presence of civil society represents an important factor for public health. However, the changes that can be observed at present cannot automatically produce results. There can be a lag between in public health changes and social policy modifications and they can not keep pace with the mood of the masses and political changes, especially when narrow interests and conservatism dominate in medical and healthcare institutions. The changes will depend on whether the masses who receive the new impulse will promote, directly or through their new representatives, new policies and practices suitable for public health. Organized civil society groups and health professionals can play a crucial role here, as together they can manage this process. In such circumstances, effective and competent leadership is of utmost importance. Dent et al. states that health professionals recognize that WHO and other international organizations have already played an important role in the development of public health in the region and promoted consolidation of its foundations in education, research, and practice (35-36). On the basis of goodwill, these organizations can facilitate further changes.

Professionals in the field of health care in every country became part of social mobilization, in case when political transformations are taking place, making the most of their social position and respect among the people in advocating the democratic movement. Indeed, once the critical situation has been resolved and modification begins, health professionals, within the framework of the health care system, are able to play a crucial role in ensuring respect for people’s demands for dignity, participation, democracy, and accountability, as much as these requirements are treated by their new governments. Thus, the responsibility of leaders in health care at each level increases many times over. In such conditions, the need for studying and borrowing best practices from world experience in healthcare leadership, with organic integration into national and regional models of management and leadership, is obvious. Health professionals can also play an important role in organizing broader health discussions in the region, from the traditionally narrow topic of health services to a wider range of social, economic, and political determinants of health.

A number of studies come to the conclusion: if the manager from his own experience understands what is necessary to perform the work at the highest level, then he is more likely to create the right working atmosphere, set adequate goals and properly evaluate the contribution of everyone (Weiss et al. 43). When the ‘model doctor’ is ‘at the helm,’ he is also able to send a signal to external interested parties (for example, new employees or patients) about the organization’s priorities.

Finally, one can expect that a talented doctor, hiring other doctors, knows what a good employee should be. It can also be assumed that medical leaders are more tolerant of “crazy ideas” (like the innovative idea of the first coronary bypass surgery performed by Rene Favarolo at the Cleveland Clinic in the late 60s). For example, the Cleveland Clinic opens up new talents and gives freedom to people with extraordinary thinking (Leggat 20). It is also important that the clinic management is ready to put up with a reasonable level of failure, which is an integral part of scientific activity and progress.

Moreover, it should be noted that within the framework of public health, it is not possible to solve the universal – and, it seems, insurmountable ‑ problem of rising costs. In many cases, attempts to control costs through government regulation lead to problems with access to health services, either to delays in providing care, or to direct regulation. Trying to solve this dilemma, many countries weaken state control and introduce market mechanisms, in particular, patient participation, market pricing of goods and services and increased competition between insurers and providers (McLaughlin 114). However, such actions in the Arab countries are unlikely to be approved, due to traditional cultural specifics.

Physicians seem to become the most effective leaders precisely because they are doctors. However, good leadership also requires social, that is, so called ‘soft,’ skills. Health care is one of the few areas where lack of teamwork can really cost patients their lives, and at the same time, doctors are not taught ‘team play.’ There is no evidence that namely team players choose the medical profession. In fact, the superiority of medical managers in hospitals seems even more outstanding when one considers the obstacles that physicians must overcome. Physicians are traditionally trained in a command-administrative atmosphere, being heroic single healers who cannot easily work together. Thus, a paradoxical situation is developing: medical training as a whole is more likely to hinder the manifestation of outstanding leadership qualities. For this reason, doctors need more systematic special leadership training.

The pioneer of one of these educational models was Paul Taheri, general director of the clinic at the Yale School of Medicine, which provides leadership training for doctors. He focused on two points: first, doctors get acquainted with the fundamental principles of doing business in the healthcare sector, and also develop personal leadership skills through a program that takes one day a month for a year. Taheri sends about forty clinic employees a year to pass it. For those doctors whose leadership qualities are manifested during this stage of training, the next step is MBA. It is noted that in leadership educational programs, doctors have always been trained along with other doctors, but they are specially “taken out” from the surroundings of a medical institution and immersed in a safe learning environment of a business school (Leggat 29). Internal programs have been developed by many other Western institutions, including Virginia Mason, Hartford Healthcare, and the University of Kentucky. There is an increasing consensus that leadership training for doctors is an extremely important matter. Such training will increase the number of leading doctors and provide great benefits from their leadership. However, in the countries of Middle East, leadership programs for doctors are not very common yet.

Distributed Leadership in Healthcare

Theoretical approaches to the definition of leadership and its models are very diverse. In particular, distributed leadership, based on the transfer of managerial functions in solving common problems, allows obtaining higher performance indicators than in case of mono-leadership, due to the effective use of employees’ competencies. If we are talking directly about leadership in healthcare organizations, it is advisable to recall the theory of “emotional intelligence” and the theory of the “engine of leadership” (Weiss et al. 30).

In the model of distributed leadership in the implementation of a specific project, leaders at different periods of time should be different people whose competencies most closely correspond to a particular phase of the project. An attempt to “generalize the conceptual and empirical literature on the concept of distributed leadership, as well as on related concepts (shared, collective, collaborative, emergent, democratic leadership, co-leadership),” was undertaken by Bolden (13-28). In his opinion, distributed leadership, on the one hand, is a means of increasing the effectiveness and involvement of staff using the leadership process as such to achieve the most favorable effect, and on the other hand, in some situations, leadership can be divided and/or democratic, but this is not at all necessary to be considered distributed one. Bolden identified three basic properties of distributed leadership: (1) leadership is a spontaneous feature of a group or network of interacting individuals; (2) openness of the boundaries of leadership takes place; (3) expert knowledge is widespread among many, not among some (13-28).

Fitzsimons, James, and Denyer proposed the following key characteristics of distributed leadership (qtd. in LeGrand 45-49):

- Leadership does not only belong to those who are assigned formal leadership roles; it is also carried out by many individuals in the organization;

- Leadership practice is formed through the leaders and followers interaction, and within the organizational context;

- Cognition is “stretched” over the participants and the contextual aspects in which they are located;

- Effectiveness implies the development of the action potential using the tools of “joint action” (concertive action), “joint activity” (co-performance) or “joint organization” (conjoint agency).

Given the complexity of the field of research on distributed leadership, as well as the presence of other forms and models of leadership related to it (joint, widespread, democratic, etc.), it seems to be impossible to establish a clear framework for the concept of “distributed leadership.” In practical application, the listed approaches are not mutually exclusive, but become more complementary to organize the interaction of participants and increase the effectiveness of joint management activities. Therefore, distributed leadership is a transferred leadership, which is determined by the priority of competencies of participants at a particular stage of activity, in frames of shaping a single team in both horizontal and vertical directions within the organization (Harris 24-35). Based on the results of a large-scale CCL study to identify the necessary competencies for the development of leadership in healthcare organizations, and also taking into account the existing theoretical approaches to distributed leadership, three key competencies that are of priority importance for the implementation of a distributed leadership model in medical organizations are identified (Weiss et al. 62-63):

- Collective management;

- The formation and restoration of relations;

- Self-awareness.

The following two questions should be considered further. Are there differences in the set of competencies of a leader in healthcare organizations in a distributed leadership model? What factors influence the formation of competencies of distributed leadership in healthcare organizations?

Experts have found that successful medical organizations usually pay great attention to the quality of medical care and close relations between medical and administrative workers, and also quickly adopt new methods of work (Henwood 12). This thesis indicates the development of such competencies as the formation and restoration of relations in the team, collective management, the presence of which is determined by developed emotional intelligence and self-awareness, which, in turn, is important when mastering new working methods.

In 2012-2013, a large-scale study of ACO (Accountable Care Organizations) was conducted, during which it was found that leadership plays a key role in the implementation of the ACO model (Turner 109). So, 51% of such organizations are managed by doctors, the share of doctors in the majority in the governing councils is 78% for such medical institutions (Turner 110). The leadership of doctors is seen as a means of collective management that helps to achieve success in changing medical practice and the financial model of medical services. It was noted that clinicians not only make decisions that determine the quality and effectiveness of patient care, but also have the technical knowledge to make a strategic choice regarding long-term approaches to providing medical services (Turner 111).

This approach, of course, leads to an increase in the volume of work performed and an increase in the cost of services. The quality of medical services is improved due to the high interest and responsibility of staff, but at the same time, resource efficiency does not increase. Up to 40% of clinic staff have a professional burnout syndrome, but nevertheless, about 36% of them are planning career growth with a leader and note improvements in the workplace, respectful attitude to staff, informing about changes in the organization, motivation to develop talents and competencies (Shanafelt et al. 433-436).

The main priority in leadership development is improving the ability to manage subordinates and work in a team. Of particular importance is the creation of an organizational culture of cooperation, involving subordinates in decision-making. Leaders need to improve their networking and problem-solving skills. At the same time, organizations in the health sector need strategies to provide a wide organizational experience, training, self-awareness for a leader, for employees capable of working across borders and interacting more effectively.

Health care has become an extremely complex industry: the balance of quality and price, technology and the human factor places increasingly high demands on physicians. These tasks require outstanding leaders; there was a time when it was believed that doctors were poorly prepared for the role of leaders, because due to the specifics of their selection and training, they most likely turned out to be “heroic lone healers,” as it was mentioned above. However, evidence clearly shows that times are changing and this fact should be taken into account. The emphasis on healthcare, where the patient is at the center of everything, as well as on efficiency in achieving medical results, leads to the fact that now doctors are prepared for leadership.

Leadership Competencies for Healthcare

Speaking about the competencies of leaders in healthcare organizations, based on the criterion of long-term success, the following general provisions can be formulated:

- In winning organizations, there are leaders at all levels;

- In order to ensure effective leadership at all levels of the organization, top-level leaders should educate leaders at lower levels of government;

- To educate new leaders, existing leaders must have the so-called teachable point of view;

- Current leaders must be proficient in the education of new leaders. In other words, it is not enough just to be a leader, but it is important that the leader is effective, able to motivate his followers and possess a pronounced emotional intelligence, which he constantly improves.

Vender defines leadership as “a combination of responsibilities, attitudes, skills and behavioral characteristics that enable an individual to highlight the best qualities in the organization’s staff to ensure sustainable development” (363). In listing the character traits and skills of a leader, the author, first of all, mentions talent, strong character, and emotional perception. The following six priority competencies for leadership development were revealed by McLaughlin (110-113):

- The involvement of staff. The ability to involve employees in the activity process is an extremely volatile skill that requires ingenuity when interacting with people. Managers and executives who are effective in personnel management invest in others and are experienced managers and motivators.

- Collective management. Effective leaders use collective management to engage others, reach consensus, and influence decision making. Managers who understand the importance of collective management encourage people around to share ideas and information, provide feedback and showcase prospects, and they listen to them. Such leaders interact well with people, keep others up to date, involve staff in the process of change, and address issues from various angles.

- The formation and restoration of relations in the team. Managers should establish and maintain strong relationships with employees based on respect, diplomacy, and fairness. Such managers are able to communicate with different people and easily enlist the support of colleagues, senior management and clients. Managers with negotiation skills fulfill their tasks using the experience of cooperation and finding a common position. At the same time, they try to understand the position of others before drawing conclusions or making decisions.

- Self-awareness. Effective leaders have a clear idea of their strengths and weaknesses and how their behavior affects others. A person with a high level of self-awareness seeks feedback and learns. He admits his own mistakes, learns from them, and moves on to correct the situation.

- Broad organizational capabilities. Leaders with broad organizational capabilities have experience working in several functional areas and interact with people whose interests, experience and points of view are competing.

- Formation and management of the team. Effective leaders choose the right combination of people in a team who together have the experience, knowledge, and skills necessary to achieve a task or carry out ongoing work. They set clear goals, resolve conflicts, and motivate team members.

In addition, there are specific challenges in managing health personnel. Thus, leaders can benefit from the development of leadership and interpersonal skills that are necessary to create focus, alignment and commitment within the organization. This task requires skills such as employee coaching, effective delegation, talent recruitment, and change through others (McLaughlin 37). It was found that achieving high organizational performance, according to employees, is possible if the leader has developed skills in resource efficiency, is straightforward, knows how to work under stressful conditions, is stress resistant, and is ready for self-learning (McLaughlin 38). Moreover, such competencies as staff involvement, collective management, the formation and restoration of relations in the team and self-awareness are of high or medium importance, but do not lead to high efficiency of the organization. The reasons for this imbalance are quite obvious: difficulties in the formation and restoration of relations in the team, solving staff problems, difficulties in introducing changes, and others mentioned above do not allow employees to understand the effectiveness of collective management, and managers to identify the potential of employees necessary to improve business performance.

Factors inhibiting the development of a leader should be noted: problems in interpersonal relationships; difficulties in forming and managing a team; difficulties in implementing changes or adaptation (resistance to changes, learning from mistakes); inability to meet business goals (difficulties in fulfilling promises and completing work); straightforwardness of functional orientation (lack of depth of control outside functions) (Bolden 129). Moreover, the real healthcare leader is most effective in the following competencies: intercultural communication, giving freedom for subordinates, and self-learning (Table 3) (McLaughlin 126).

Table 3: Leadership Effectiveness: Health Leaders Performance

The traditional classification of power and leadership effectiveness offers five types of power (or influence): the power of reward, coercion, expert, and legitimate and referential power. Each type of power has its own characteristic features of implementation, conventionally called “commitment,” “consent,” and “resistance” (Turner 82). The most favorable option ‑ commitment ‑ is possible if the subordinate and the leader have a common goal and the leader’s requests are convincing; a less favorable outcome in the form of consent is realized if the subordinate is indifferent to the goals set. Resistance to the leader, as an active avoidance of his requests or demands, arises if the leader’s behavior is arrogant and insulting. From this position, it is of interest to predict leadership success for the leader of the medical team.

Studies of the social position of the leader, his personal characteristics showed that not only the quality of ‘production,’ but also the psychological climate in the team and the satisfaction of the performers by the work largely depend on the level of leader’s qualifications and focus of his activities (Bolden 12). According to the literature on leadership qualities and skills, the most important personal characteristic of a leader is the level of development of his organizational and communicative traits. The results of the research using the KOS-2 method showed that the majority of “bosses” (67.2%) showed high organizational qualities (of which: gradations “high” ‑ 33.6% and “very high” ‑ 33.6%), a half showed communicative qualities (of which: 16.6% ‑ “high,” 33.4% ‑ “very high,” p> 0.05). The number of persons with low indicators of the considered qualities is insignificant (communicative ‑ 8.3%, organizational ‑ 16.4%, p> 0.05). Moreover, the communicative qualities of gradations “high” and “very high” are more common among general practitioners (14.2% versus 7.1%) and non-treatment doctors (22.5% versus 9.0%), p <0.05. The average value of the indicator of organizational qualities in the group of bosses is higher than communicative (M ± m are respectively 14.6 ± 0.97 and 13.2 ± 0.89, p <0.05). The average communicative and organizational abilities of doctors in this group are higher than in other groups (p <0.05 with indicators of model groups of doctors) (Turner 87).

Thus, despite its legitimate origin, leadership in medical professions has an expert nature of influence. Leaders, as a rule, are ‘shaped’ professionals with at least 10-15 years of work experience and certain leadership qualities and skills. At the same time, negative tendencies in the personal positions of leading doctors complicate the implementation of leadership roles and lead to stress in the psychological situation in the team, which is a risk factor for the development of social and professional maladaptation. In particular, the low level of communicative control and emotional disturbances in communication manifested by a number of doctors in the group of bosses are risk factors for implementing such a form of ineffective leadership as the “resistance” of subordinates. In turn, the high level of communicative and organizational abilities of leaders allows predicting the high effectiveness of the role functions of these leaders in the form of “commitment” of subordinates.

An analysis of the professional biography of doctors in the model group of managers in one of the empirical studies allowed researchers to conclude that leadership in medical professions, according to the traditional classification of power (French & Raven, 1960), is represented by the power of an expert, the source of which is the experience, knowledge, and abilities of a person perceived by colleagues. If, for other areas of expertise, the expert’s competence may not affect interpersonal relations, and leadership remains informal, then for the head doctor, it is the type of influence that is formalized into leadership supported by legitimate authorities. For the medical profession, there is such an expert-corporate concept as “consultation” (council of physicians), the decision of which is determined by the reference influence of more experienced and competent professionals.

In particular, the achievements of modern medicine and primarily surgery are largely associated with the development of anesthesiology and intensive care. The effective work of medical organizations largely depends on the proper organization of the work of the heads of resuscitation and anesthesiology departments of medical institutions, which ensure a clear rhythm and coordination in the work of the entire medical organization, solve issues of systematic professional development of employees, monitor the quality of medical care, and contribute to the creation of good psychological climate in the team and the introduction of the latest diagnostic and treatment methods. The first ranking places in the list of functions of the department head are occupied by various types of work with the team for the control of work, training, education. Moreover, the list of managerial functions is quite wide, and they are associated with the coordination of work, operational regulation of situations, planning and monitoring the implementation of plans, team motivation, organization of innovations, work with documents of different plans, communication.

The authors suggest some definite strategies for the implementation of managerial competencies divided according to the functional basis for achieving management goals, represented by four main groups (Turner 64-65):

- Control strategies aimed at monitoring business situations. These include regulation of activities, a regular reporting system, regular group sessions, arrangement of working hours, encouragement and punishment, and the creation of a motivation system.

- Stabilizing strategies to maintain stable service relationships in the dyad “head-employee.” This is the creation of traditions, the definition of norms and values, the formation of a corporate culture, the stability of interpersonal relationships and the predictability of managerial decisions, the uninterrupted operation of technical means, and the stability of material conditions.

- Strategies for employee development. Such strategies include professional development, creating conditions for personal growth, staff rotation, conducting professional contests, seminars, conferences, mentoring, creating an evaluation and career development system, and creating a reserve for leading positions.

- Transforming strategies reflecting the change and improvement of circumstances in the innovative direction: creating an innovative environment, encouraging innovation, supporting innovative, creative solutions, critical thinking.

The development of managerial competence of middle managers involves the allocation of a system of its determinants, the necessary psychological and acmeological conditions and factors. Acmeological factors are grouped as follows. General objective means psychological requirements for the profession, the introduction of a diagnostic center for personnel assessment, as well as the formation of a reserve group for promotion; general objective-subjective ones mean psychological readiness of managers for the very process of developing managerial competence and the practical implementation of existing managerial knowledge and skills; general subjective ones are related to the effectiveness of the leader, his competitiveness.

Special (specific) factors are innovation, credibility, cooperation, discipline, mentoring. In the healthcare sector, these factors contribute to the achievement of high performance indicators, affect the success and professional and personal development of managers. Identified psychological factors are closely interrelated; their structure is mobile and depends on the specifics of the professional activities of managers. The components of the determination of managerial competence do not exhaust the entire complexity of this phenomenon, which necessitated the development of a psychological and acmeological model that indirectly reflects the totality of its components which imitate the development of managerial competence of middle managers – for example, heads of anesthesiology and intensive care units.

Accordingly, technological support for the process of developing leadership and managerial competence of middle managers is represented as psychological and acmeological support in the form of a comprehensive program, for example (Turner 67-69):

- Organizational and procedural. It is represented by the strategy aimed at the realization of managerial competencies and is grounded on the implementation of such factors as “demand, professionalism, the possibility of development, continuous development, continuous self-education, a favorable acmeological environment, and a positive image” (Turner 67-70).

- Innovatively developing. This block is based on the development of such qualities as innovation, credibility, discipline, cooperation, mentoring. At this stage, training is being conducted on the development of strategies for implementing managerial competencies.

The development of managerial competencies and strategies for their implementation as a system involves the development of each type and ensuring their integration. The training program for leaders can be built on the basis of an analysis of the identified managerial competencies and strategies for their implementation and is intended for mid-level managers of a medical organization with management experience of up to two years. In the process of training, topics can be presented that contribute to the development of managerial competence, while positively influencing the motivation of activity and individual psychological characteristics. The training course for leaders can be conducted on the basis of independent modules, each of which has semantic completeness. In the course of work mini-lectures, business cases, group discussions, exercises and role-playing games with video feedback can be used.

At the reflective-analytical stage, the tasks of forming the presentation and concentration of participants’ attention on one of the main characteristics of managerial activity ‑ its focus ‑ are solved. Participants should be invited to analyze their own work experience through a structured interview. The work takes place in pairs, where one of the participants interviews the other to determine the focus of his/her activities as a leader. To achieve this goal, participants in several small groups also analyze the situations proposed by the trainer for analysis. The result represents leaders’ understanding of the direction of managerial activity: the individual, the team, the result, and self-understanding.

In the process of further work, an interactive session can be held to identify the dominant strategies that managers use to achieve management goals. The result of this part of the training is the understanding by managers of their own strategies for implementing managerial competencies and their systematization. The purpose of the modular phase is to improve and develop strategies for the implementation of managerial competencies. In the group of managers, four subgroups can be distinguished, working on a modular basis on various issues of managerial competence:

- Module 1. Value-based management competence.

- Module 2. Normally-oriented managerial competence.

- Module 3. Individually-oriented managerial competence.

- Module 4. Collectively-oriented management competence.

In each module, one can consider four groups of strategies for implementing managerial competencies: controlling, stabilizing, developing, transforming. During the work, interactive sessions and group discussions are used. It is rational to build questions for discussion in subgroups on the basis of the presented modules. The goal of the final transformative-implementing stage of the training is the implementation in practice of the knowledge gained in the second stage. Leaders can be divided into two groups: expert observers and practical implementers (implementing executive). The result of work in this block will represent a reflective analysis of an expert observer and the experience gained by the implementing executive.

It is expected that, when conducting psychological training, the average values of creativity indicators are increased, affecting the development of skills of creatively, non-standard approach to solving business issues and tasks. As a result of the training, changes should take place in the preferred behavioral strategies ‑ in particular, the decrease in average group-wide indicator for the domination and withdrawal strategies can be observed, while the indicators for the cooperation and compromise strategies are increasing (Turner 70). Thus, it is obvious that after the training, managers will prefer to choose the most effective strategies for behavior in a conflict situation, which are cooperation and compromise. In a difficult situation of choice on significant aspects of interaction with people, the actions of leaders are aimed at resolving conflict situations without undue tension (as is the case with the use of a domination strategy).

Also, it should be noted that among the methods of describing leadership existing today, the most effective is the method of describing leadership behavior through a set of key competencies. Competencies are qualitatively different from the earlier practice of enumerating personality traits in that the emphasis is placed on behavior as an external manifestation of these traits in combination with skills and knowledge through the prism of motivational components. The ability to observe the degree of manifestation of competencies under the condition of a pre-compiled model allows evaluating their expressiveness in a particular person in objective manner.

Healthcare Leaders’ Skills in Change Management

Unlike the terms widely accepted in the literature that characterize organizational or structural changes and their management at the organization level, the authors in the field of healthcare define the concept of “change” as a change in the position of the object under consideration or its constituent parts (blocks), taking into account the choice of new areas of activity of the object leading to qualitative transformations of his condition, and the concept of “change management,” in turn, is defined as a targeted impact of active actors in various fields of activity in order to increase efficiency, competitiveness both at the organization level and at the industry level, as well as influence the economy as a whole (Suchman 22).

In recent years, the organization of effective medical activity in healthcare institutions has been regarded as multi-level, built on the principles of strategic management and marketing, using the tools of change in the process of reforming the industry and individual organizations (Suchman 30). According to the concept of organizational development, a medical institution should be considered holistically. Leaders must think and work simultaneously at four different levels (Gabel 11-13):

- Operational: what kind of activity are we doing well, should we continue in the same direction?

- Corrective: what are we not doing well and what needs to be improved? Where is the “disease” of our organization?

- Perspective: what new should we introduce in order to expand the coverage of the population, improve the quality or increase the market share?

- Preventive: what do we need to keep under control in order to prevent failure and not to collide with the iceberg?

The organizational development of a medical institution can be represented in the form of the following aspects: 1) the stages and processes through which the organization passes as it grows and ripens; 2) “diagnosis” and “treatment” to achieve the best position of the organization in making changes in response to the actions of external and internal factors. Change Management represents a continuous, cyclical process that includes the following elements: determining the purpose of the organization; statement of individual tasks (concreteness, measurability, attainability, acceptance, limitation of funds, written fixation, indication of terms); definition of roles (innovative tasks ‑ changes in work and increasing efficiency; operational tasks; personnel tasks); personal development planning; making changes; final check. In addition, it is proposed to evaluate changes to consider the performance management system as a process that (Suchman 60):

- Combines the goals of the organization with the individual tasks of its employees;

- Allows employees to receive regular feedback on their results;

- Provides a basis for identifying personal development needs of individual employees;

Moreover, the assessment of the leadership of changes at the level of the head of the healthcare organization includes determining the degree of effectiveness of the organization, namely, the situations are possible when the head:

- Systematically transforms the main aspects of the organization’s work, seeks to create such an organizational climate when changes become the norm, and existing practice is constantly being reviewed;

- Actively seeks the possibility of significant changes in many areas, anticipates changes long before they occur, and therefore the leader is well prepared for changes; always welcomes changes and actively encourages new ideas of the organization;

- Regularly initiates changes; anticipates all obvious changes; always welcomes changes and carries them out with optimism;

- Often initiates changes. Anticipating obvious changes, the leader honestly tries to adapt to them. Generally welcomed changes and new ideas;

- Takes the initiative regarding changes, but only under pressure from outside; anticipates most, but not all, of the obvious changes; sometimes makes no attempt to adapt to them; may be reluctant to make changes, but when the purpose of the changes is clear, he responds to them;

- Rarely is the initiator of changes; cannot anticipate or prepare for change; is hostile to new ideas.

The change management system in medical institutions, especially in the context of industry reforms, provides significant assistance to managers, allowing them to follow a systematic approach to managing the process of change in the organization, identifying and solving tasks involving changing job functions and the formation of new skills that are needed according to the reform, and finally providing clear accountability. In addition, the introduction of changes is based on feedback, which leads to improved performance, including systematic self-monitoring, the necessary reassessment, and so on in a spiral upward. The stated approach assumes an ever-increasing role of individual medical institutions in the process of increasing the effectiveness of healthcare.

Since modern management is focused on everything new (concepts, theories, models, technologies), it will be very interesting to analyze, as best practice, the experience of the world-famous American clinic Mayo, existing since the 1900s, the activity of which indicates the possibility of using the correct concept of organization management for many decades. American Mayo Clinic is the world’s first comprehensive non-profit medical multifunctional organization that unites almost all specialties into a common system of doctors, unlike most highly specialized medical institutions in the United States. About 80% of the clinic’s doctors take part in scientific research, and there are Nobel laureates.

The success of the organization and the longevity of its brand are explained by brilliant clinical results, multifunctional service, and effective change management. As a result of the use of system engineering in the organization, the application of the Six Sigma quality improvement program, the following results were achieved: the time required for patients to complete all prescriptions was reduced by 60%; net operating profit over three years increased by 40%; each patient’s service time was reduced by 6 minutes; the number of daily prescriptions increased, which gave an additional income of more than 4 million dollars in a year; 24-hour work of diagnostic laboratories accelerated diagnosis and reduced hospitalization time (Gabel 40-41). An example of a Mayo clinic demonstrates success in the field of healthcare management: as a result of self-organization, the institution is constantly evolving; the staff is self-learning. Moreover, Mayo Clinic’s Career and Leadership Program offers training in managing change.

It is interesting to note that, despite the diametrically opposed health models in different countries, in particular when comparing the countries of Middle East and the countries of West, there are examples of solving problems through successful innovations, when a specific shortcoming of a country’s health system turns into an advantage or new opportunities, like in countries experienced Arab Spring events, which was mentioned above. Thus, “radical innovation” are possible – for example, private health insurance as the fastest growing and most popular component of the benefits package provided by the employer to employees. However, in the context of rising health care costs, there is another innovation ‑ “separation,” that is, the transfer of a whole range of medical services requiring high costs from hospitals to other places (Gabel 18-19). Thus, attempts with different vectors can be made: either to reduce the planned priority for free treatment, or to optimize costs by creating outpatient surgical centers, hotel-treatment complexes, etc.

It is obvious that changes in the organization of healthcare as an open socio-economic system are organizational, technological, informational, economic, and other innovations, the implementation of which is based on their interconnection and mutual influence, taking into account industry specifics. Changes in health care contribute to success (increase in efficiency) if they focus not on one variable, but simultaneously on several. At the regional or municipal level (at the mesoscale), change management should include the following: improving the system of planning and economic support of healthcare based on modern industry norms and standards, taking into account the incidence rate and the needs of the population for types of medical care, reasonable cost standards; the introduction of programs to reduce morbidity and mortality, resource optimization based on methods of economic and mathematical modeling, a program-targeted approach.

Change management in healthcare organizations (at the micro level) to a critical degree depends precisely on the competence of leaders and should be based on a synthesis of multi-level and integrative approaches, ensuring the achievement of a synergistic effect from the introduction of innovations at the macro-, meso- and micro levels. To effectively manage change in healthcare organizations, it is necessary to provide the following:

- Create a change management model from interconnected control units for the design, implementation, motivation, evaluation, informational support of changes using the information-analytical system, which will allow building a single, interconnected change management process;

- Establish the optimal proportions of production processes and resource support of medical services to achieve medical, social, economic efficiency;

In an organization, as an open system, the mission of a formal leader is to approve and ensure the implementation of a strategy of regular changes aimed at constantly improving the effectiveness of the organization. The basis for the successful implementation of changes is the idea of their implementation. The idea of making changes cannot arise in the minds of ordinary employees or management representatives, and then make their way upstairs. However, the easiest, shortest, and, therefore, effective way of carrying out organizational changes is the path that is initiated by representatives of the organization’ leadership, who have full power to implement the idea, as well as sufficient personal authority to form a ‘camp’ of supporters of reforms and strengthen the driving forces for change. In order to achieve maximum results in the creation of constructive ideas regarding the implementation of organizational changes, a leader can act in two directions:

- As the creator of the psychological climate and conditions that allow gaining confidence in the need for change;

- As an organizer, that uses his status and power, individual influence and organizational resources to restructure the organization, resolve conflicts between individual employees or departments.

The effectiveness of change management is associated with the agreement between the leader and most of the organization’s employees regarding the goals of the reform. In order to reach agreement on the goals of the change, the leader must solve a number of problems (Gabel 63-65):

- Define the purpose of the changes in concepts and terms that are accessible to the understanding of the ‘bulk’ of employees. A defined goal should be easily remembered by members of the organization.

- Build and develop confidence in the idea and goals of change.

- Develop a common vision of the goal.

- Develop change strategies on this basis.

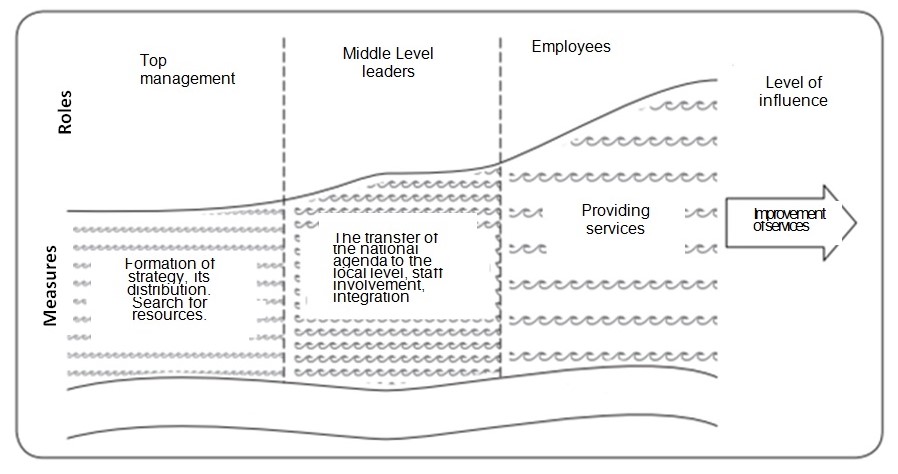

The extent to which changes implementation is effective is associated with the formal leader’ activities in the process of shaping responsibility for the changes end result, for all categories of subordinates: senior management, middle management, and ordinary employees. The responsible attitude of subordinates to their duties is directly related to ensuring their respective powers and freedom of decision-making. At the same time, close connection and integration of individual goals and interests of group members with organizational goals, implementation of needs, representation and protection of interests of both individual group members and the team as a whole is necessary. This eliminates the possibility of the activity of destructive groups and leaders, which are detrimental to the organization, and also increases the authority of the leader in the eyes of employees and the importance of business leadership compared to purely emotional one.

Leadership under the Conditions of Turbulence in Healthcare

The theoretical basis of modern research in the field of organizational leadership is the approach according to which one cannot become an effective manager without being a leader, and vice versa. In other words, management and leadership are regarded as identical or closely interrelated phenomena. Consideration of management and leadership as synonymous concepts is also possible because effective leaders play two main roles ‑ charismatic and architectural. The charismatic role is the person’s ability to predict the future, motivate and inspire employees based on this vision. Performing an architectural role, the leader solves issues related to the structure of the organization, planning, control system, and encouragement of subordinates. Thus, a leader cannot exist only in one of these ‘forms,’ as each of them is of great importance in a management situation. This is especially important when external environment in the industry is highly dynamic and even turbulent. Namely this can be observed in today healthcare industry in the Middle East, mainly due to instability of political and social situation throughout the Middle East region.

Such exceptional turbulence of the external environment determines the need for leaders to be able to accept challenges and act effectively in the face of change. In an increasingly unpredictable and competitive modern dynamic economy, business entities require a new, high-quality form of leadership (creative, innovative, effective, project, transformational, responsible, charismatic, political, etc.). Health organizations are increasingly faced with the need for change, so today, more than ever, the ability of leaders to lead in transitional times is being tested. It is advisable for organizations operating in a complex dynamic environment with a high degree of uncertainty to permanently change. In this regard, the ability to carry out changes, to respond flexibly to them, to adapt to changing environmental conditions or, even more significantly, to directly change the environment itself, is the most important characteristic of modern market participants, ensuring their long-term competitiveness. Change management skills are particularly important in such circumstances.

Optimization is often limited to staff reduction measures: layoffs under the guise of restructuring. It is possible that in the conditions of merciless competition, it will be necessary to make a painful decision to reduce staff ‑ anyway, to ‘lose weight in front of a marathon’ (Leggat 127). However, weight loss alone will not lead to victory in the race. To win, one needs to fight hard; instead of the usual cost reduction, a leader should think about initiatives that will give advantages in the medium term, stimulate growth, actions that will fundamentally change the work of the organization and, importantly, investment in leadership and talent development.

In rapidly changing conditions, there is an increasing need for creative leaders ‑ those who act proactively, predict and direct the intentions of others, constantly discover something new and understand that people are driven by emotions. Their activities, first of all, are aimed at the following: increasing the efficiency of creative and intellectual activities, overcoming the deficit of ideas, rethinking the concept of development, maximizing the use of followers’ creative and team potential. Creative leaders can turn challenges into opportunities; therefore, it is clear that in modern conditions of reality, it is not power leaders who win, but creative leaders.

When Satya Nadella became Microsoft CEO in February 2014, he delved into the ambitious transformation process to make the company competitive in the field of mobile and cloud technologies. This process included strategic, organizational, and cultural change. At that time, Microsoft’s culture was based on internal competition, which did not facilitate learning. Nadella approached the problem thoroughly ‑ he laid the foundation of leadership for his vision of life and a culture of learning. The goal of the employees was not a limited desire to look smarter against the background of others, but the desire to grow, listen, learn, and awaken the best qualities in people. From the very first days, Microsoft employees noticed these changes in culture ‑ a vivid example of the fact that for Microsoft the interests of people have become a priority. Although this example does not apply to the healthcare sector, it nevertheless represents one of the best practices appropriate for use by leading physicians.

Studies show that effective leaders are characterized by the use of different management styles that they apply depending on the situation and the task at hand (Henwood 97). It is difficult to act flexibly, Daniel Goleman noted, but one can learn this, and it is necessary to pay attention to it, as a variety of leadership styles helps increase the effectiveness of the organization (qtd. in Henwood 99).

It is known that the main theories of leadership include the following: the theory of personality traits, situational theory, the theory of the determining role of followers. Recently, the so-called relational theory (“synthetic” approach to leadership) has appeared and gained popularity, whose supporters are trying to synthesize the above approaches and overcome their limitations.

The availability of leadership training opportunities (theory of leadership training) is also indicated by many significant factors. Systematizing professional literature, it can be noted that the conclusions of many studies indicate the importance of using a large number of styles by managers. The practice of successful leaders shows the importance of an imperceptible transition from one style to another depending on the situation (LeGrand 9). Recognizing the importance of leadership development, it is advisable to determine the leadership qualities that need to be used and developed, and in a certain way restructure the personnel development system, organizational culture, in order to timely identify potential leaders, educate them, and professionally promote them in organizations.

We can say that the range of qualities that a leader needs at the stage of innovative transformations should include a number of important elements: global thinking, the ability to anticipate new opportunities, the desire to develop staff, creativity, ingenuity, the ability to work with a team and partners, support for constructive innovations, a sense of change, technological competence, desire for competitive advantage, personal excellence. Leadership in the modern world is transforming ‑ it is the leadership of innovation and change, the leadership of progressive innovative teams. Innovative leadership requires not to stop at some point but to look ahead, form new trends and be especially sensitive to possible shortcomings, preventing their development into serious problems.

Today, healthcare organizations are actively implementing innovative ideas through the development of innovative projects, overcoming resistance to changes, and implementing innovative projects with a high degree of effectiveness. Thus, the project leadership competency is realized, which is included in the organizational block of competencies and, accordingly, the characteristics represented by the initiative and the results, and it will undoubtedly occupy one of the important positions in the competency model of managerial talent (Scott 85).

The basis for the implementation of project leadership is the project culture ‑ a relatively new, but very relevant and significant component of the professional culture of the modern leader, which must be actively developed and enhanced due to its progressiveness, vitality, practical orientation, cultural conformity, meeting the needs of the formation of a new quality and contributing to the formation of social maturity of staff. The project culture should be considered as the basis of the leader’s readiness for innovation, the development and implementation of new technologies, representing a combination of different project methods for transforming reality, actively using modern methods of forecasting, strategic and operational planning, design, execution and evaluation of the achievement of the planned indices (Turner 26-29). It is advisable to cite the following as arguments in favor of the need for the formation and development of a project culture: acts as a kind of problem-solving education; defines a new, modern, innovation-oriented look of any business entity; contributes to a change in the type of thinking of project participants; implements innovative ideas of a personality-oriented approach; changes the competitiveness of the organization and the leader himself.

It is important to emphasize that the achievement of the results is facilitated by transformational leadership, that is, a unique style in which the leader’s commitment to help people with whom he actively collaborates is positioned; he helps them build a professional career, improve their qualifications and grow. On the other hand, this type of leadership helps to unleash the power of followers. Leaders are focused on creating a training organization, and as a result, an atmosphere is created that facilitates the transformation of the system. In order to be a transformational leader, it is needed to have creative potential.

In recent years, a large number of institutes, training centers and experts on the problems of leadership development have appeared. However, the challenge for many people in health care industry is still to master effective leadership methods. This is explained by the inadequacy of quantitative research showing which management style contributes to the achievement of positive results. Knowledge of theories does not provide an answer to the problematic issues of the development of a medical organization, but sets the course of action. However, following some concept, it is necessary to realize and take into account the presence of a number of features that complicate the development of leadership qualities. At the same time, still, the most ideal leader is a type that combines emotional, business, and informational components. It is necessary to be able not only to consider abilities in people, but also to find stimulating mechanisms for their disclosure, thereby demonstrating responsible leadership, i.e., creating an environment in which people and entire organizations move together towards their desired goals through self-development.