Introduction

On a global scale, depression is considered a severe disabling health concern characterized by the high prevalence rates. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a debilitating illness defined by a minimum of one discrete depressive episode for at least two weeks. It involves the distinct “changes in mood, interests, and pleasure, as well as changes in cognition and vegetative symptoms” (Otte et al., 2016, p. 2). Such a disease leads to considerable impairment and is prevalent for one’s entire life. According to Kupfer, Frank & Phillips (2016), MDD has a “12-month prevalence of 6×6% and a lifetime prevalence of 16×2%” and occurs twice as many in women as in men (p. 266). Moreover, depression provokes significant decrements in health that are akin to other chronic diseases’ implications. With that said, primary care providers must recognize depression when patients have a chronic physical disorder.

Exposome

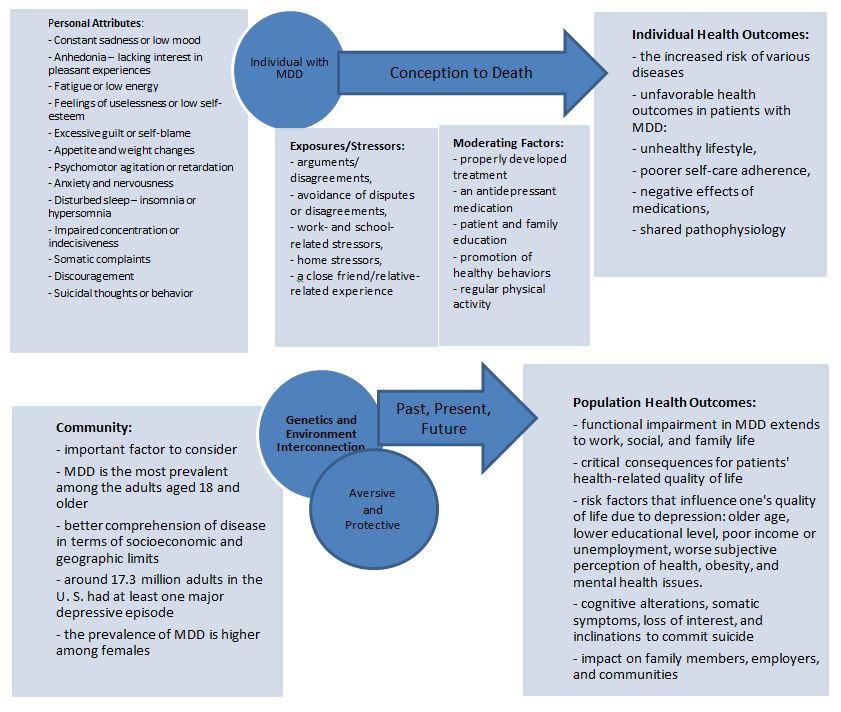

The public health exposome is considered a comprehensive exposure tracking system for incorporating complex relations between exogenous and endogenous exposures throughout one’s life from conception to death. This conceptual structure helps understand the environmental context of the examined health outcomes regarding a particular disease (Juarez et al., 2015). Concerning this research, there have been no reports of the dominant or recessive forms of MDD. Most importantly, depressive disorder is characterized by a complex trait, which implies that the risk is affected by DNA sequence variants throughout the genome and specific psychological and physiological environmental factors. The purpose of exposure science is to determine fundamental, common systems and shared biological pathways grounded in a broad spectrum of complex diseases. Such conceptual models enable the development of aimed personal and community health interventions.

Public Health Exposome Model

The public health exposome conceptual model will help determine the contributions of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors to many forms of depressive disorder. As such, one will be enabled to find solutions to decrease the risk of depression and provide adequate treatment. Shadrina, Bondarenko & Slominsky (2018) state that the predisposition to depressive disorder is defined by the concerted action of multiple genes and their interaction with each other and with various environmental causes. In addition, every gene by itself is likely to make a relatively minor contribution to the pathogenesis of the disease.

The exposome model depicts the dynamic linkage between personal attributes, stressors, community, individual, exposures, environment, moderating factors, and health outcomes across the life. Thus, the purpose of this exposome model is to analyze the exposomic influences on health and apply a holistic approach to assess health care in a population regarding MDD. The primary focus of tins research is to illustrate specific environmental influences related to major depressive disorder by implementing the Public Health Exposome Model (Fig. 1) and, therefore, enhance a better understanding of factors that influence and promote such a disease.

Individual

The lifelong incidence of major depressive disorder comprises 6.2% among adolescents and up to 19% among adults. As such, MDD is one of the most common disabling health conditions on the international level. The beginning of the disease usually occurs at an early stage in life, considering that most individuals experience major depressive disorder during adolescence (McIntyre, 2020). It is a highly recurrent illness, which means that individuals with MDD might experience the second episode at a particular moment in their life. It is also important to mention that depression has an adverse impact and provokes the excess mortality rates, whether through suicide (direct impact) or comorbid chronic conditions (indirect impact). According to McIntyre (2020), mortality risks increase to 60 – 80% (p. 1). MDD also has a significant influence on society in general by causing a loss in productivity and prolonged living with such disability. Therefore, major depressive disorder is currently perceived as the leading cause of disease burden worldwide by the next decade.

Personal Attributes

Major depression is associated with the co-occurrence of the set of specific symptoms that serve as the general framework for the DD diagnosis. Depressive disorders cover one of the most common and prevalent forms of psychiatric pathology. Following the ideas of Shadrina, Bondarenko & Slominsky (2018), depression, as a serious diagnosis, encompasses many adverse consequences with “medical and sociological relevance,” which affects one’s quality of life and adaptive skills (p. 2). More specifically, the long-term major depressive disorder, coupled with chronic somatic or neurological conditions, may result in attempted suicide.

Among the key symptoms of MDD, anhedonia is considered the most defining symptom. It entails the loss of ability for the affected individual to experience enjoyable activities. Hence, it is a crucial part of the clinical assessment of MDD to determine the life pursuits of the patient and track them over time to understand the course of the disease and recovery. Strakowski & Nelson (2015) define the following MDD symptoms:

- Constant sadness or low mood

- Anhedonia – lacking interest in pleasant experiences

- Fatigue or low energy

- Feelings of uselessness or low self-esteem

- Excessive guilt or self-blame

- Appetite and weight changes

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation

- Anxiety and nervousness

- Disturbed sleep – insomnia or hypersomnia

- Impaired concentration or indecisiveness

- Somatic complaints

- Discouragement

- Suicidal thoughts or behavior

Genetics and Environment

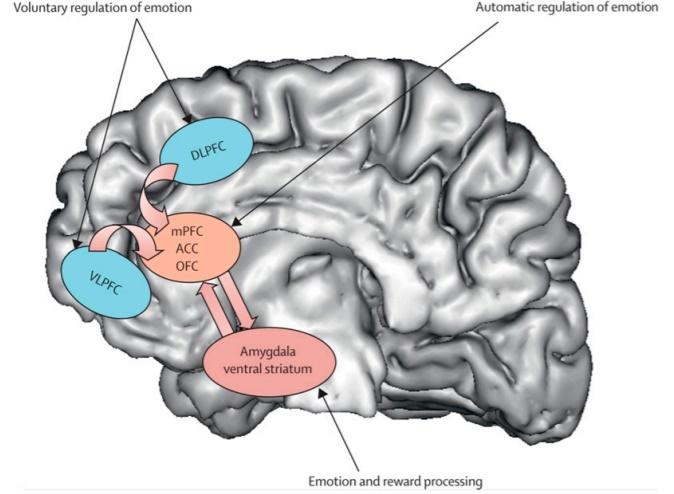

The in-depth examination of genetic and environmental determinants of major depressive disorder, as well as their interaction, is a valuable source for preventing depression and informing its clinical treatment. Major depressive disorder is a genetically complex trait with a compound etiology (Fig. 2). Multiple genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are based on the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) analysis in terms of their association with the disease. According to the research conducted by Dunn et al. (2015), the effect of most SNPs is small in magnitude, “allelic odd ratios of around 1.3 or less” (p. 3). Genetics and environment studies propose a diathesis-stress model, wherein a genetic liability is engaged with a stressful life event that causes depression. Within such a model, the genes enhance or mitigate the effects of stress. In addition, the concept of genetic and environmental determinants also involves positive implications of the environment, including “social support, psychosocial interventions, and other protective factors” that can eliminate the risk of disease (Ward et al., 2017, p. 5). Different genetic variation makes people react negatively to adverse environments and more positively to beneficial settings.

The interaction between genetics and environment is crucial in identifying the extent to which genetic variants change the correlation between environmental determinants and DD. Depression has a various genetic architecture, which refers to the number of genetic loci connected with a “phenotype, the effect size of each locus, and the loci behavior” (Dunn et al., 2015, p. 6). The psychiatric disorders are considered to be polygenic or provoked by multiple genes. Therefore, the genetic foundation of depression might incorporate even larger loci of individually small effect. Concerning that depression is defined by a large number of loci of weak effect, it might be effective to mix genetic signals across many SNPs into operationally established gene sets (pathways). The majority of research is focused on various candidate gene markers, such as:

- 5-HTTLPR,

- BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor),

- MAOA (monoamine oxidase A),

- FKBP5 (FK506 binding protein 51),

- CRHR1 (corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1),

- COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase),

- CREB1 (responsive element-binding protein 1).

Furthermore, other environmental factors are based on stressful life events, whether the recent ones or in childhood, and on child maltreatment, including physical or sexual abuse. It is important to note that children’s ill-treatment is one of the most powerful environmental stressors in the etiology and course of MDD. Child abuse is proved to enhance the risk of internalizing problems, including major depressive disorder. The genetic liability to MDD reflects three different symptom dimensions: “psychomotor/cognitive, mood, and neurovegetative” (Hollander et al., 2020, p. 4). Putative intermediate phenotypes or endophenotypes associated with the depressive disorder include emotion-based attention biases, impaired reward function, and deficits in executive functioning domains, such as learning and memory.

Community

The surrounding community defines the health of each individual and is, thus, an essential factor to consider. The target population for this exposome model research is the adult populace in the United States, considering that major depressive disorder is the most prevalent among adults aged 18 and older. Such an approach that examines health consequences within its biological, social, ecological, and community framework facilitates better comprehension of disease in terms of socioeconomic and geographic limits. According to NIH (National Institute of Mental Health, 2019) statistics, around 17.3 million adults in the United States had at least one major depressive episode, which comprises the 7.1% of the entire U.S. adult population. On the gender level, the prevalence of MDD is higher among females than males and is 8.7%. As for 2017, around 11 million American adults aged 18 or older had at least one major depressive episode with severe impairment, which covers 4.5% of all U.S. adults.

Stressors/Exposures

A chronic state of stress and various stressful life events occurring early in life are strong predictors of the onset of depression. The long-term activation of the stress system causes harmful or even fatal outcomes by elevating the risk of depression and other disorders. The Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA system) axis has three main components accountable for adaptation to changed environmental conditions and the organism’s reaction during exposure to stress. The “stress-induced theory” of depressive disorder is grounded in the assumption that hyperactivity of the HPA system is an essential mechanism underlying the development of depression after exposure to stress.

The researchers analyzed the documented exposure to any of the six naturally emerging psychosocial stressors every day. They include arguments or disagreements, avoidance of disputes or disagreements, work- and school-related stressors, home factors, a close friend/relative-related experience that was stressful for the individual, and any other stressful event. Greaney, Koffer, Saunders, Almeida & Alexander (2019) state that a psychosocial stressor has short-term detrimental outcomes for microvascular endothelial function only evident in young adults with MDD. However, the relative absence of psychosocial stress might be vasoprotective for adults with MDD. With that said, the psychological stress regulates the interconnection between depressive symptomology and impairments in flow-mediated dilation. The severe psychological stressors promote a clear cardiovascular response and give valuable information concerning mental stress-induced alterations in bodily function.

Moderating Factors

In terms of major depressive disorder, there is no way to prevent the disease, but detecting depression ay the early stage can significantly help with combating the issue. A properly developed treatment can help both reduce the symptoms and prevent from the MDD reoccurrence. Antidepressant medication is commonly recommended as the form of initial treatment for patients with MDD (Phillips, Chase, Sheline, Etkin, Almeida, Deckersbach & Trivedi, 2015). Patient and family education are as well considered to be highly efficient in moderating the development of the major depressive disorder. Such education involves promoting healthy behaviors, including good sleep hygiene, decreased consumption of caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, and other potentially harmful substances. Moreover, incorporating the regular exercise routine has a considerably positive impact on overall health, including improvements in mood symptoms for patients with MDD (Morres et al., 2018). This might involve particular aerobic exercises or resistance training. Thus, regular physical activity can reduce the prevalence of depressive symptomology in the general population with a specific benefit for the adult group and patients with co-occurring medical conditions.

Individual Health Outcomes

Concerning somatic consequences of major depressive disorder, longitudinal studies’ meta-analyses showed that individuals with MDD are more inclined to the higher risk of various diseases. To be more specific, the factors that contribute to different somatic consequences of depressive disorders are complicated and might clarify the unfavorable health outcomes in patients with MDD. Individual health outcomes regarding patients with major depressive disorder include unhealthy lifestyle, lower self-care adherence, adverse effects of prescribed drugs, and shared pathophysiology (Chevance et al., 2020). For instance, the last one can involve the upregulation of immune–endocrine stress systems associated with MDD.

Population Health Outcomes

The target population for this research is the adult population in the United States as the most affected group of American society by the MDD diagnosis. According to Baune & Christensen (2019), the functional impairment peculiar to patients with MDD “extends to work, social, and family life” and has critical consequences for their health-related quality of life (p. 2). Based on various nationwide studies, multiple risk factors influence one’s quality of life due to depression (Cho et al., 2019). Such factors encompass older age, lower educational level, poor income or unemployment, worse personal understanding of health, and mental health issues (Clarke, Skoufalos, Medalia & Fendrick, 2016). Altogether, they refer to the quality of life impairments in individuals with depressive disorders.

Regarding the age factor, depression in later life is characterized by an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, the elderly with DD have a risk of cognitive alterations, somatic outcomes, loss of interest, and tendency to commit suicide. The exposure to many physical and mental disturbances causes severe health disorders that meet medical modifications that cover “neurological, cardiovascular, endocrine, inflammatory, and musculoskeletal changes” (Hasin, Sarvet, Meyers, Saha, Ruan, Stohl & Grant, 2018, p. 337). Annually, millions of Americans are diagnosed with depressive disorders, which has serious implications for the patients and their family members, employers, and communities. Understanding the challenges of MDD from different perspectives, including patients, physical and mental health professionals, community service agencies, and policymakers, is crucial for developing an efficient strategy for improving the US mental health system.

Role of the Health Care Provider

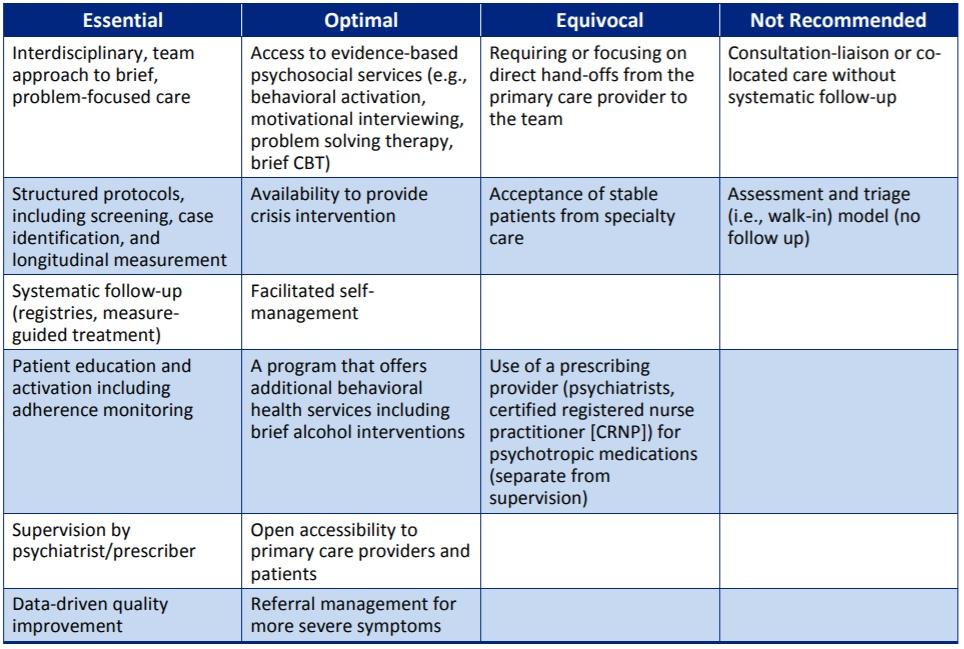

The health care providers significantly contribute to the major depressive disorder therapy since it is a clinical diagnosis, which has to be treated accordingly (Fig. 3). The medical professionals are trained in many different specialties to determine the depression symptoms. Casarella (2020) provides a detailed list of care providers who are qualified to treat MDD. Such health professionals include physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and psychiatric nurse specialists. The physicians who are skilled in primary care medicine and are qualified in treating mental or psychiatric concerns can help treat depression. In the case of acute depressive symptoms, doctors recommend specialized care for patients.

The physician assistants are trained to identify DD symptoms and treat mental or psychiatric disorders under a physician’s control. Registered nurses with specified nursing training also play a crucial role in addressing cognitive or psychiatric problems. Psychiatrists specialize in the diagnosis and treatment of mental or psychiatric conditions. They are also licensed to prescribe medications as part of DD treatment and are qualified in psychotherapy. The psychologists are skilled in counseling, psychotherapy, and psychological testing. The social workers provide essential mental health services for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. Finally, psychiatric nurse specialists are educated in psychiatric nursing and can help with mental or psychiatric illnesses. With that said, health care providers play a fundamental role in combatting the MDD symptoms and critical health outcomes by enhancing and maintaining the individual’s physical, psychological, and social functioning.

Conclusion

A major depressive disorder is a complex mental condition that has a considerable impact on the overall health and wellness of oneself and the entire society. This in-depth analysis of MDD from both individual and population perspectives is crucial to effectively address and manage this illness and improve the health of all Americans. The Public Health Exposome Model is a helpful approach in understanding the genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors that contribute to depressive disorders. The exposome conceptual model helps define the solutions to eliminate the risk of MDD and provide adequate treatment by healthcare professionals.

Major depression is examined through the lens of personal attributes, community, stressors/exposures, moderating factors, as well as individual and population health outcomes. One of the most critical factors regarding MDD and its implications on public health implies its linage to other severe health conditions. Individuals diagnosed with major depression usually face several additional chronics, behavioral health, and pain-sensitive health conditions. Such transformative health concern is studied in terms of the target community, the adult population, as the most affected by this health issue. This research is a crucial step in defining the most efficient methods for physicians to treat MDD and help patients achieve fast recovery and improve overall health.

References

Baune, B. T., & Christensen, M. C. (2019). Differences in perceptions of major depressive disorder symptoms and treatment priorities between patients and health care providers across the acute, post-Acute, and remission phases of depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 1–10.

Casarella, J. (2020). Depression: Where to seek care. WebMD Medical Reference. Web.

Chevance, A., Ravaud, P., Tomlinson, A., Le Berre, C., Teufer, B., Touboul, S., Fried, E. I., Gartlehner, G., Cipriani, A., & Tran, V. T. (2020). Identifying outcomes for depression that matter to patients, informal caregivers, and healthcare professionals: qualitative content analysis of a large international online survey. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(8), 692–702.

Cho, Y., Lee, J. K., Kim, D.-H., Park, J.-H., Choi, M., Kim, H.-J., Nam, M.-J., Lee, K.-U., Han, K., & Park, Y.-G. (2019). Factors associated with quality of life in patients with depression: A nationwide population-based study. PLOS ONE, 14(7), e0219455.

Clarke, J. L., Skoufalos, A., Medalia, A., & Fendrick, A. M. (2016). Improving health outcomes for patients with depression: A population health imperative. Report on an Expert Panel Meeting. Population Health Management, 19(S2), S–1–S–12.

Dunn, E. C., Brown, R. C., Dai, Y., Rosand, J., Nugent, N. R., Amstadter, A. B., & Smoller, J. W. (2015). Genetic determinants of depression. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23(1), 1–18.

Greaney, J. L., Koffer, R. E., Saunders, E. F. H., Almeida, D. M., & Alexander, L. M. (2019). Self‐reported everyday psychosocial stressors are associated with greater impairments in endothelial function in young adults with major depressive disorder. Journal of the American Heart Association, 8(4), 1–9.

Hasin, D. S., Sarvet, A. L., Meyers, J. L., Saha, T. D., Ruan, W. J., Stohl, M., & Grant, B. F. (2018). Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 336.

Hollander, J. A., Cory-Slechta, D. A., Jacka, F. N., Szabo, S. T., Guilarte, T. R., Bilbo, S. D., Mattingly, C. J., Moy, S. S., Haroon, E., Hornig, M., Levin, E. D., Pletnikov, M. V., Zehr, J. L., McAllister, K. A., Dzierlenga, A. L., Garton, A. E., Lawler, C. P., & Ladd-Acosta, C. (2020). Beyond the looking glass: recent advances in understanding the impact of environmental exposures on neuropsychiatric disease. Neuropsychopharmacology.

Juarez, P., Matthews-Juarez, P., Hood, D., I., W., Levine, R., Kilbourne, B., Langston, M. A., Al-Hamdan, M. Z., Crosson, W. L., Estes. M. G., Estes, S. M., Agboto, V. K., Robinson, P., Wilson, P., & Lichtveld, M. (2015). The public health exposome: A population-based, exposure science approach to health disparities research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(12), 12866–12895.

Kupfer, D. J., Frank, E., & Phillips, M. L. (2016). Major depressive disorder: New clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. FOCUS, 14(2), 266–276.

McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Major depressive disorder. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Morres, I. D., Hatzigeorgiadis, A., Stathi, A., Comoutos, N., Arpin-Cribbie, C., Krommidas, C., & Theodorakis, Y. (2018). Aerobic exercise for adult patients with major depressive disorder in mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 36, 39–53.

NIH, National Institute of Mental Health (2019). Major Depression. Web.

Otte, C., Gold, S. M., Penninx, B. W., Pariante, C. M., Etkin, A., Fava, M., Mohr, D. C., & Schatzberg, A. F. (2016). Major depressive disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2, 16065.

Phillips, M. L., Chase, H. W., Sheline, Y. I., Etkin, A., Almeida, J. R. C., Deckersbach, T., & Trivedi, M. H. (2015). Identifying predictors, moderators, and mediators of antidepressant response in major depressive disorder: Neuroimaging approaches. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(2), 124–138.

Shadrina, M., Bondarenko, E. A., & Slominsky, P. A. (2018). Genetics factors in major depression disease. Front. Psychiatry, 9(334), 1–18.

Strakowski, S. M., & Nelson, E. (2015). Major depressive disorder. Oxford University Press.

The Management of Major Depressive Disorder Working Group (2016). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of major depressive disorder. Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Defense.

Ward, J., Strawbridge, R., Bailey, M., Graham, N., Ferguson, A., Lyall, D., Cullen, B., Lyall, L., Cavanagh, J., Mackay, D., Pell, J., O’Donovan, M., Escott-Price, V., & Smith, D. (2017). Genome-wide analysis in UK Biobank identifies four loci associated with mood instability and genetic correlation with major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder and schizophrenia. Translational Psychiatry. 7(1264), 1–9.