Introduction

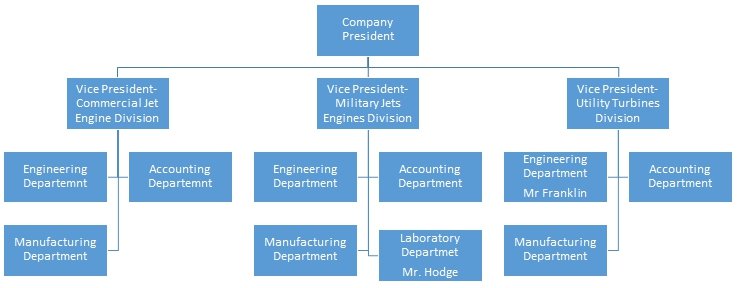

After the Tucker Company adopted the above organizational structure, the interdepartmental conflict between Mr. Hodge and Mr. Franklin had both personality and structural bases.

The Structural Basis

The new organizational structure adopted by the Tucker Company was classical in nature as many industrial oriented organizations are not (Spender, 1989). In following a structure formulated along product lines it adopted the basic principles of division of labor which is itself an integral aspect of the classical theory of management (Almashaqba et al, 2001).

In the classical theory of management, success is based on a few basic principles. Foremost, the notions of authority and responsibity are intimately intertwined (Almashaqba et al, 2001). In accepting to exercise your authority in a particular area, you also, out of necessity, accept the responsibilities inherent in it.

The second principle is that of unity of command. This principle states that each person should only receive commands from a single source (Almashaqba et al, 2001). This is because multiple commands would lead to confusion, and eventually conflict. A third principle is that of unity of direction.

It states that members of an organization should work towards the achievement of similar overt goals (Almashaqba et al, 2001). It is in the unity of objectives that harmony within the organization is achieved. Lastly, member of the organization are expected to harmonize their interests with those of the organization.

If there is conflict between the two, individual interests should be subordinated to those of the organization; this is called the principle of Subordination of Individual Interest (Almashaqba et al, 2001).

Due to its hierarchical nature, Tucker Company’s new structure falls in the bureaucratic subgroup of the classical theory of management which can be summarily characterized by a few features. Foremost, bureaucracy is typified by specialization. Job positions and the corresponding are offered to persons who are most qualified in carrying them out (Mullins, 2005).

It is also characterized by hierarchical authority which is reliant on levels that are vertically oriented (Mullins, 2005). For a bureaucracy to work, it is regulated by a system of rules and regulations. These rules are understood to be of utmost importance and as such they cannot and should not be subordinated to personalities (Mullins, 2005). These principles should have served to avoid conflict at the Tucker Company. They were however undermined by structural oversights, limited resources, divergent personality types and the neglect of these principles by members of staff as will be shown below.

To start with, the reorganization of the company into three main divisions whose vise-presidents were directly and independently answerable to the company president meant that they were autonomous from each other. This arrangement per se is not the cause of the ensuing conflict. Rather, it led to the fact that the company did not have access to unlimited resources to ensure that the implied concept of autonomy was not just theoretical. Since the company could not afford to equip and staff entire laboratories for each division, it carried on with the previously operational arrangement where the Laboratory, which was structurally under the Military Jet Engines Division, would serve all the other divisions. This was the mistake.

The resultant cross-departmental interaction had great potential for conflict. This is because the Classical theory of management is characterized by vertically oriented relationships. There were therefore no clear stipulations of how Mr. Franklin and Mr. Hodges, coming from different divisions and answering to different authorities, should have related.

In this respect, the conflict between the two can be blamed on either the incapacity or unwillingness of the company to actualize the autonomy of the three divisions or on the inability of the classical theory to facilitate healthy horizontal interaction.

As has been aforementioned, the classical management theory seeks to dispel ambiguity by regulating relationships by means of clearly laid down rules and guidelines. Such guidelines assist in reducing uncertainty in interdepartmental interaction which in turn aids performance (Hickson et al, 1971). This was however not the case in respect to Mr. Franklin and Mr. Hodges. In light of the probable efficiency of Mr. Hodges’ predecessor, there had never been need to establish such guidelines.

The restructuring of the company should however have been implemented as an opportunity to introduce the codification of such guidelines in light of the existing evidence that they are effective in reducing the number of opportunity for interdepartmental conflict and in providing means of conflict resolution (Smythe, 2000). The company management overlooked the potential danger of relying on the personal efficiency of Mr. Garfield and the risk of assuming that his replacement would be equally effective.

The Personality Basis

The conflict between Mr. Franklin and Mr. Hodges could also be looked at from the human perspective. Foremost, Mr. Hodges filled a position previously occupied by Mr. Garfield. It is significant to note that Mr. Garfield had efficiently fulfilled his duties and managed to satisfy all the departments that relied on his lab. The fact Mr. Hodges was unable to do this is a clear indication of a personality perspective to this conflict.

Secondly, Mr. Hodges was overlooking the authority and responsibility principle of the classical theory of management when he sought to have a say in the material selection process of Mr. Franklin’s department.

The fact that Mr. Hodges would not have been found answerable were something to go wrong is evidence enough that he should not have been accorded such authority. Having risen to the level of head of department Mr. Hodges would be expected to understand the workings of the new structure adopted by the company. Therefore, that he made such demands is a pointer to a personality weakness.

Lastly, the basis that Mr. Hodges raises for making these demands is that he feels he would be better at doing the job than Mr. Franklin owing to his training as a metallurgist. This constitutes lack of professional courtesy towards Mr. Franklin.

Implicit in this assertion is his questioning of Mr. Franklin’s capability to fulfill his responsibility and as well as the means by which he came to hold the position of head of manufacturing. Mr. Franklin also shows a weakness of character in hanging up on Mr. Hodge. This reaction might be attributable to the apparent perception of Mr. Hodges as a difficult man who only cares for his own interests at the expense of the company’s and others’.

Recommended Structure

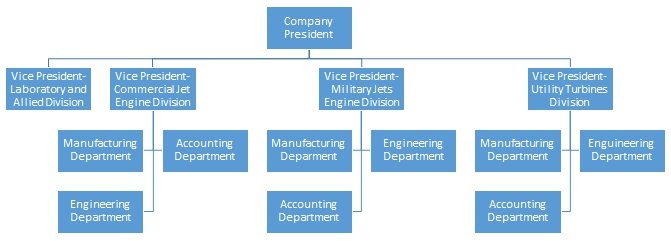

It is clear that the conflict between Mr. Franklin and Mr. Hodges was a complex matter. However, it would have been avoided by restructuring the organization as follow:

The new Laboratory and Allied Division, coupled with a codification of regulations guiding its interaction with other divisions, would be advantageous in that it would eliminate structural and resource sharing problems discussed above.

Its main disadvantage is that it would be costly to establish a fully functional Laboratory and Allied Division. It would also still be beset by those that arise from personality differences and the neglect of observance of rules and regulations. Still, it would be the best.

References

Almashaqba, Z., Alajloni, M., & Al-Qeed, M. 2001. The Classical Theory of Organization and its Relevance. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 41: 60-67.

Hickson, D., Hinings C., Lee, C., Schneck, R. & Pennings J. 1971. A Strategic Contingencies’ Theory of Intraorganizational Power. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16(2): 216-229.

Mullins, J. 2005. Management & Organizational Behaviour. New York: Prentice Hall.

Smythe, E. 2000. Antecedents of Interdepartmental Conflict in Cross-Functional Enterprise Integration Project Teams. PACIS 2000 Proceedings. Paper 68. Web.

Spender, J. 1989. Industrial Recipes: An Inquiry into the Nature and Sources of Managerial Judgment. London: Basil Blackwell Ltd.