Abstract

This background science review will discuss research on drills and training in relation to seafarers’ hours of rest. It will target studies that focus on the regulatory basis of drills and training as well as hours of rest in the maritime industry. This review aims to illuminate the current understanding of the potential impacts of compliance with drill requirements, or lack thereof, on onboard crews’ repose periods.

Previous research has demonstrated a contentious relationship between the two domains, suggesting that seafarers suffer numerous adverse consequences from their precarious, undermanned work environment, tinged with exacting job requirements, including frequent training and drills. However, academics are yet to strike a consensus regarding the direct consequences of these drills on on-board crewmembers’ hours of rest. This background science review thus aims to formulate a basis for understanding the research that exists on this topic as a precursor to formulating a suitable empirical study to bridge the identified knowledge gap.

Accidents at sea remain unacceptably high despite technological development (Maritime accident fatalities in the EU, 2022). In marine transport, training and drills have traditionally been seen as the most effective way to equip seafarers with the skills they need for efficient accomplishment of their duties and the eventual reduction of mishaps (Shemon, Hasan and Kadir, 2019). In the Republic of Korea alone, navigator error was attributed to 79% of all incidents in the past five years (Rip, 2018). To understand the human causes of these mistakes, it is vital to investigate the relationship between fatigue on-board and the exercises required of seafarers.

Defining On-Board Drills and Rest Hours

This section entails a definition of the terms around which this review is centred. Drills in the marine transport context refer to methods of practising how crewmembers should behave during an emergency (Dragomir & Utureanu, 2016). The marine transport sector can be extremely dangerous since it is vulnerable to many potential hazards, including but not limited to ship grounding, capsizing, vessel sinking, fire, explosions, and pirate attacks.

Risk analysis of incidences of vessel or cargo damage and loss, injuries, and deaths ranks the sea as the most hazard-prone environment (Lu and Tsai, 2008). Considering the fact that harsh weather conditions in the marine environment can impede external help during an emergency (Burciu et al., 2020), the need for self-sufficiency and emergency preparedness cannot be overemphasised for seafarers. Hence, Baksh et al. (2018) viewed risk assessment and readiness for eventualities as a promising way to ensure that those involved respond appropriately. The responses may include relocating people to safer areas to lessen the extent of damage when a hazard strikes.

The importance of training notwithstanding, crewmembers need sufficient rest to replenish energy and perform optimally. It is common for “rest hour” to be presumed similar to and used interchangeably with “work break,” but they mean different things. According to the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), rest hours on-board refer to the period a seafarer is relieved of duty, excluding the short breaks during normal work hours. This definition suggests that work breaks differ from rest hours in that they are shorter and typically taken while an individual is still on duty.

Standards Regulating Drills/Training and Seafarers Resting Hours

While reviewing drills and training on board ship, Dragomir and Utureanu (2016) recognised the International Conference on the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention as the most crucial treaty regarding maritime transport security. SOLAS 1974, which came into force around mid-1980, requires all its over 165 contracting states to comply with specific minimum safety standards for constructing, equipping, and operating merchant ships. The Convention, created, a creation of the IMO, further entails specific mandatory drills that a vessel must perform to enhance voyage safety and security.

Complying with regulatory requirements can easily overwhelm seafarers with training and drills. Table 1 below presents just a summary of current drilling regulations according to SOLAS’s latest requirements. It is constructed with special attention to, where applicable, how frequently these drills are required.

Table 1: SOLAS on-board drills requirements

According to the International Labour Organisation’s Maritime Labour Notice (MLN) Regulations, all seafarers are entitled to at least 10 hours of rest in any 24-hour period, which translates to a minimum of 77 hours per week (MLN 2.3, n.d.). They further require scheduling firefighting, musters, and lifeboat drills such that they do not induce fatigue or disturb rest. The guidelines further recommend providing compensatory rest hours whenever duty interferes with normal break time. However, the persistence of accidents in the marine transport sector despite the long list of rules and regulations emphasising training and drills suggests a gap in knowledge and practice.

Noncompliance With Rest Hour Regulations

Violating the standards regulating seafarers’ hours of rest is a common practice. Accordingly, a more important question to ask is to what extent these subversions occur. In a case study of deck officers’ working and resting hours on oil tankers that navigated coastal waters, Uğurlu (2016) found gross violations of work and rest regulations. The researcher found that first and second officers worked over 15 hours for 16 and 20 days, respectively, rested less than six hours within any previous 24 hours at least 79% of the time, and generally breached work and rest conventions almost always (Uğurlu, 2016, p. 11). A major shortcoming of this study is its limited focus, which excludes vessels with heavy tonnage; this makes it impossible to generalise findings to understand the graveness of the violations on an industry-wide level.

A recent insider look into the normative behaviour in seafaring suggested that violations of rest hours are not widespread but are also normalised through the ‘ethos of ship first’ (Baumler, Bhatia and Kitada, 2021). Through a qualitative research design that administered semi-structured interviews to 20 seafarers, Baumler, Bhatia, and Kitada (2021) determined that nearly all participants manipulated work and rest hours’ records to hide violations of foreign compliance.

Lee et al. (2021) provided further evidence of systemic adjustments to records when they reported that most crewmembers believed that their working hours were not accurately recorded. Baumler, Bhatia and Kitada (2021) further accused Flag State, Port State, and shipping companies of complicity in understaffing ships and conditioning seafarers to endure unfavourable work conditions to protect the ship first. This source also suffers from a great generalisability deficit because of its qualitative design and small sample.

A quantitative study involving 284 participants drawn from maritime universities and over 40 companies investigated problems encountered during on-board training and how they were managed (Lee et al., 2021). Lee et al. (2021) found that the respondents lacked sufficient rest time and personal protective equipment. The authors found that all but 21% of the cadets worked more than 8 hours a day (Lee et al., 2021). An intriguing revelation of this study is that training occurred outside normal work schedules and was used to get the cadets to complete otherwise payable tasks, some of which they found uncomfortable, such as extra maintenance work and private errands (Lee et al., 2021). Although this study draws significant generalisability strength from its quantitative design, its choice of participants may not be an accurate reflection of the European marine work environment.

Drills and Training vs Crew’s Hours of Rest

On-board training sessions can elicit detrimental impacts that diminish the quality of crews’ rest periods. A prime example is the emotional or physical injuries sustained from sexual harassment and abuse during drills. As can be inferred from Acas’s (2021) definition, any unwanted behaviour of sexual nature that offends, intimidates, humiliates, degrades, or violates the dignity of someone constitutes sexual harassment. If this conduct occurs at least once without the recipient’s consent or full understanding and harms them in any way, then it qualifies as abuse. Conversely, studies have found that on-board training can be rife with sexual harassment against mostly female seafarers (Lee et al., 2021), perpetrated predominantly by their male counterparts (Tangi, 2020).

In a comprehensive mixed-methods study conducted as part of the Gender Empowerment and Multicultural Crew Project with participants drawn from China, Nigeria, and the UK, Pike et al. (2021) found that cadets expected to encounter sexual harassment during training. These fears were confirmed after embarking from the first training, when about one in six women working at sea experienced or witnessed sexual harassment (Pike et al., 2021). Despite a comprehensive approach tinged with a global view, the study does not illuminate the impact of the challenges it identifies on hours of rest. Moreover, its exclusive focus on female seafarers, who the authors note only account for 2% of seafarers globally, undermines its external validity.

Another way to understand the overarching implications of on-board drills and training is to consider them within the context of the precarious marine environment. During voyages, seafarers have to operate peculiar on-board equipment while enduring the risk of falling overboard and other potential triggers of many traumatic and psycho-emotional conditions (Dachev and Lazarov, 2015). Moreover, seafarers could suffer from ultraviolet deficiency, seasickness, overheating or overcooling of the body, and other adverse health effects due to the hydro-meteorological conditions of the marine environment (Dachev and Lazarov, 2015). Conscious of these dangers, Dachev and Lazarov (2015) warned that prolonged exposure to the dangerous work conditions at sea could lead to chronic illnesses, affecting seafarers’ quality of life ashore. Although this study recommends more training and awareness as potential ways of mitigating these health risks, it fails to consider how the potentially degraded health of seafarers could affect their rest hours.

Another potential negative impact of drills and training is fatigue. Mounting evidence indicts exhaustion as a risk factor for undesirable injuries and accidents, including ship grounding (Galieriková, Dávid and Sosedová, 2020; Hawley, 2019; Paolo et al., 2021). Recent studies have further demonstrated a positive association between excessive work demands, including working under vigilance demands and time pressure, and chronic fatigue (Andrei et al., 2020; Galieriková, Dávid and Sosedová, 2020).

In their recent descriptive study, Jinoo et al. (2017) assessed the effectiveness of MLN Regulations on Work and Rest Hours from the experience of cadets and seafarers working on-board international vessels. They discovered that, for cadets, the MLN regulations provided little guarantee for leisure. Cadets had to apportion some of their rest hours for training, studying, and mandatory drills (Jinoo et al., 2017). Of the studies hitherto reviewed, Jinoo and colleagues present plausible evidence suggesting that training and drills deny cadets’ valuable time to restore energy after busy periods on-board, potentially increasing the chances of occupational hazards. However, the study’s descriptive quantitative design undermines its ability to determine in-depth employee experiences regarding the impact of drills and training on rest hours, subject to MLN regulations.

Some scholars have rejected the suggestion that excessive training and drills cause fatigue. Rather, they argue that fatigue is one of the many factors that hinder compliance with regulatory requirements on on-board drills, hence the enduring lack of emergency preparedness and the eventual ineffective response to disasters (Tac, Akyuz and Celik, 2020). Validating this view, (Van Cutsem et al. (2017) explained that physical and mental fatigue decreases motivation, mental concentration, and alertness.

Tac, Akyuz, and Celik (2020) concluded that while rules are sufficient in number, they have not succeeded in enhancing emergency preparedness due to implementation deficiencies. The high prevalence of fatigue among seafarers is a prime indicator that rest is a limiting factor in this environment. Yet the reviewed literature suggests that denying crewmembers sufficient time to relax and regain energy instigates cascading consequences.

Gaps in Existing Research

The background scientific review has revealed some interesting insights regarding the study area. It has been shown that credible research has significantly contributed to unpacking the convoluted interplay of rules and regulations, seafarers’ wellbeing, and safety in the maritime industry. However, it is concerning that on-board training as a potential threat to crewmembers’ wellbeing has eluded the attention of many researchers.

A possible explanation for this continued lack of attention is the general assumption that training and drills aim at enhancing the safety of everyone on-board, including the participating seafarers. Few researchers have been intrigued by the gratuitous fatigue to which training and drills subject crewmembers. It is also possible that most decision makers are detached from the on-board reality of seafarers, thereby impeding their ability to understand how drills could be the prime culprit in perpetuating fatigue, thereby jeopardising ship safety.

Besides the skewed understanding of the effectiveness of drills, few studies attempt to understand why it is so difficult to allow seafarers enough time to recover from their exacting job requirements. Notably, it would be challenging to give a crewmember at least ten hours of rest per day when a ship is undermanned in the first place. Research by BIMCO/ISF (2016) shows that the global maritime industry has a shortfall of 16,500 seafarers and projects the workforce shortage to rise to about 147, 000 by 2025. However, scholars have challenged the reliability of BIMCO/ISF findings, citing methodological flaws (Tang and Bhattacharya, 2021).

For example, Tang and Bhattacharya (2021) presented counterexamples showing that there is a workforce oversupply. Tang further recommended focusing on providing quality training instead of spreading resources and efforts thinly to expand training capacities. Despite the apparent lack of consensus on whether there is a labour shortage in the seafaring industry, it is clear that seafarers face serious training challenges, which also affect their wellbeing. The proposed research will thus offer a comprehensive view of the problem by appreciating that lack of sufficient rest among seafarers is a confluence of many factors, including on-board training and drills.

The general thrust of the reviewed literature stresses the importance of training for the on-board crew. However, a paucity of knowledge exists regarding the impact of these drills on crewmembers’ hours of rest. Accordingly, the proposed study aims to explore the underlying effects of the vaunted training and drills on seafarers’ on-board rest periods. A hypothesis for this study will be created and accepted or rejected after testing under experimental conditions. The collected data will also be subjected to a t-test to validate hypotheses and enable further in-depth analysis that will inform the project’s overarching conclusion.

Project Plan

Proposed Project Title

How Do On-board Training and Drills Impact Crew Members’ Hours of Rest?

Null Hypothesis

A crew member’s rest hours are not negatively impacted by drills conducted during off-duty hours.

Alternative Hypothesis

Drills held during off duty hours have a detrimental effect upon a crewmember’s hours of rest.

Research Question

How do drills held during off duty hours affect seafarers’ hours of rest?

Methodology

To understand how the current practise of training and drills affect on-board crews’ hours of rest, the proposed study will adopt a cross-sectional quantitative design. The research design is preferred because its emphasis on measurement at a single point in time and limited active interference with participants make it relatively cheap and ethically uncomplicated. Moreover, it will allow the researcher to demonstrate the relationship between drills and their negative effects on seafarers’ repose periods. The study will strive for internal validity by controlling for potential confounders. This will be achieved through the study design, participant recruitment, and analysis.

The researcher will also seek ethical clearance and conduct a risk assessment at the appropriate study stages, in strict observance of the university guidelines.

Sampling

Sampling for the study will be based on two considerations. Firstly, it will strive for representativeness by ensuring that research participants have a direct and quantifiable relationship with the general seafaring population. Secondly, a large sample will be needed to accurately reflect the broader population. The proposed hypothesis will be tested and accepted or rejected following a comprehensive review of available data and a questionnaire that will be answered by naval officers.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire will include closed ended questions to obtain ordinal data. The survey will collect demographic data (e.g., age, sex), information on training and drilling activities (duration, frequency, and type of drill), and quality of rest time (ranked on a Likert scale). Participants will be asked to rate on a Likert scale their answers to questions related to on-board drills and training. The responses will then be numbered so that the researcher can test them statistically. This process will strengthen the reliability of data sets and any subsequent analysis.

Data Analysis

The study will employ a multivariate analysis to analyse the collected statistical data. Specifically, Pearson’s correlation test will be used to assess the strength and direction of the relationship between drills and seafarers’ hours of rest.

Research Resources

The researcher will require access to a maritime research database and other relevant sources of credible academic papers. These publications will be used as the foundation for a comprehensive literature review on the subject. The researcher will also need a means to create and distribute the questionnaire, preferably through Google Forms. Other requirements will include an ethics form and SPSS statistics.

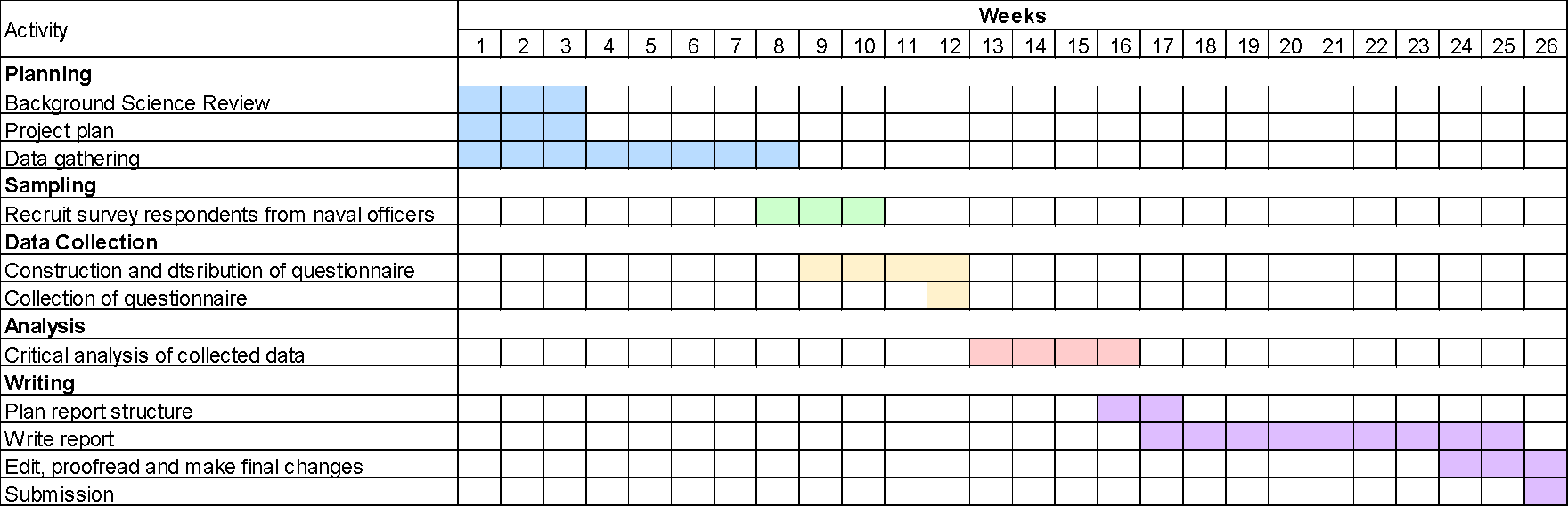

Project Timeline

The Gantt chart below shows a breakdown of activities that will be completed as part of this study. The researcher aims to achieve all project milestones between November 2022 and May 2023.

Reference List

Acas. (2021). Understanding bullying, harassment and discrimination: Handling a bullying, harassment or discrimination complaint at work, Acas. Web.

Andrei, D.M. et al. (2020). ‘How demands and resources impact chronic fatigue in the maritime industry. The mediating effect of acute fatigue, sleep quality and recovery’, Safety Science 121, 362–372.

Baksh, A.A. et al. (2018). ‘Marine transportation risk assessment using Bayesian Network: application to Arctic waters’, Ocean Engineering, 159, pp.422-436.

Baumler, R., Bhatia, B.S. and Kitada, M. (2021). ‘Ship first: Seafarers’ adjustment of records on work and rest hours’, Marine Policy 130.

BIMCO/ ICF. (2016). Manpower report: The global supply and demand for seafarers in 2015. Maritime International Secretarial Services Limited; BIMCO/ICS: London, UK.

Burciu, Z. et al. (2020). ‘The impact of the improved search object detection on the SAR action success probability in maritime transport,’ Sensors, 20(14), p. 3962. Web.

Dachev, Y. and Lazarov, I. (2019). ‘Impact of the marine environment on the health and efficiency of seafarers’, Wseas Transactions on Business and Economics, 16, pp.282-287.

Dragomir, C., and Utureanu, S. (2016). ‘Drills and training on board ship in maritime transport’, Ovidius University Annals: Economic Sciences Series, 16, 323–328.

International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), 1974. (no date). International Maritime Organization. Web.

Galieriková, A., Dávid, A. and Sosedová, J. (2020). ‘Fatigue in maritime transport’, Scientific Journal of Bielsko-Biala School of Finance and Law, 24(1), pp. 35-38.

Jinoo, R. V., Caldo, C. P. E., Pasilan, C. L. A., Segovia, A. F., & Estimo, E. T. (2017). Implementation, compliance, and effectiveness of maritime labor convention regulations on work and rest hours, in: 18th Annual General Assembly of the International Association of Maritime Universities – Global Perspectives in MET: Towards Sustainable, Green and Integrated Maritime Transport, IAMU 2017. Nikola Vaptsarov Naval Academy, pp. 146–153.

Hawley, R.A. (2019). ‘Fatigue at sea and maritime accidents’, Lynchburg Journal of Medical Science, 1(3), pp. 33.

Lee, J. et al. (2021). Korean maritime cadets’ onboard training environment survey. Sustainability, 13(8), pp. 4161.

Lu, C.S. and Tsai, C.L. (2008). ‘The effects of safety climate on vessel accidents in the container shipping context’, Accident Analysis and Prevention 40, pp. 594–601.

Maritime accident fatalities in the EU (2022) Statistics Explained. Web.

MLN 2.3. (no date). MLC title 2.3 hours of work and hours of rest. Department of Economic Development. Web.

Paolo, F., Gianfranco, F., Luca, F., Marco, M., Andrea, M., Francesco, M., Vittorio, P., Mattia, P. and Patrizia, S. (2021). ‘Investigating the role of the human element in maritime accidents using semi-supervised hierarchical methods,’ Transportation Research Procedia, 52, pp. 252–259. Web.

Pike, K., Wadsworth, E., Honebon, S., Broadhurst, E., Zhao, M. and Zhang, P. (2021). ‘Gender in the maritime space: how can the experiences of women seafarers working in the UK shipping industry be improved?’, Journal of Navigation 74, pp. 1238–1251.

Rip, A. (2018). “Constructive technology assessment,” in Futures of science and technology in society. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer, pp. 94–117.

Shemon, W.S., Hasan, K.R. and Kadir, A. (2019). Human resources competitiveness in shipping industry: Bangladesh perspective. In Message from The Conference Chairs, pp. 251.

Tac, B.O., Akyuz, E. and Celik, M. (2020). Analysis of performance influence factors on shipboard drills to improve ship emergency preparedness at sea, International Journal of Shipping and Transport Logistics, pp. 117–145.

Tang, L., Bhattacharya, S. (2021). Revisiting the shortage of seafarer officers: a new approach to analysing statistical data, WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs 20, pp. 483–496.

Tangi, L. (2020). ‘Uniting against the tides: Filipino ‘shefarers’ organising against sexual harassment,’ IDS Bulletin, 51(2). Web.

Uğurlu, Ö. (2016). ‘A case study related to the improvement of working and rest hours of oil tanker deck officers’, Maritime Policy and Management, 43, pp. 524–539.

Van Cutsem, J., Marcora, S., De Pauw, K., Bailey, S., Meeusen, R. and Roelands, B. (2017). ‘The effects of mental fatigue on physical performance: a systematic review,’ Sports Medicine, 47(8), pp. 1569–1588. Web.