Background of the Study/Literature Review

Concepts and Theories

Brand image is a construct that dates back to the 1950s, Dobni and Zinkhan (1990) maintain, albeit without the benefit of a universally accepted and precise definition other than that the concept embraces all the intangibles and added value unique to each brand. Accordingly, brand image is everything that is created and extrinsic to product composition and function.

It is the sum total of all decisions involved in the marketing mix: packaging form factor and size, label, pricing, advertising strategy, execution, the “editorial” environment of all media used, the credibility and charm of celebrity endorsers, the quality of promotions and incentives, and merchandising (Kotler & Keller, 2008).

In turn, “brand association” refers to the phenomenon of a given brand standing for the physical product attributes and consumer benefits of the product category as a whole. ‘Guinness’ is so dominant among English ales, for example, that it has come to stand as ‘generic term’ for this drinks category. Similarly, ‘Pampers’ is the name most widely associated with disposable diapers and is therefore the brand shoppers readily recall and inquire for when looking around the hypermarket for the aisles holding the product class.

‘Brand image’ is evidently more all-encompassing but also more vulnerable than ‘brand association’. The brand image of Apple Inc. is the sum total of marketing communication and product development choices made by the maverick Steve Jobs. These included the decision to create the user-friendly home computer and graphic user interface long before Windows was even a gleam in the eye of Bill Gates. There was outstanding advertising creative: “Big Brother’ and ‘Lemmings’ that established the “not IBM’ positioning of the brand a generation ago. The decision to re-launch the company with forays into portable music players (iPod), touch screen mobile phones (iPhone), and now a tablet PC (iPad) have all rested on creating a niche market with a near-fanatic following. Along the way, it is also true that brand association across the entire Apple line never strayed far from ‘cool,’ ‘cutting edge’, maximum functionality, ease of use and amazing entertainment value.

And yet, brand image is also vulnerable. Nike and Accenture signed up Tiger Woods as celebrity endorser in order for the first to maintain its cachet as sportswear for winners while the software services company looked to lift itself from obscurity where the general public was concerned. When the golfer’s marital scandal surfaced, the two were quick to cancel all advertising featuring the golfer for fear their respective brand images would also be subject to ridicule.

More to the point is what happened to Toyota, the largest automaker in the world by unit sales. Just last January, Consumer Reports continued to rank Toyota in first place for value, quality technology, innovation, and concern for th environment (Pearce & Purser, 2010). Today, the recall of millions of units of virtually all the company’s stellar models reveal a pattern of neglect that has seriously tarnished its reputation for quality. Unless car owners are willing to trade off safety for the low prices of imports, chances are one more disastrous round of vehicle recalls or a vigorous regulatory response by host governments will send the carmaker into a tailspin from which recovery will be very difficult.

In contemporary times, there is another, very significant element to brand image and this has to do with reputation. Reputation includes the good governance and sustainable competition aspects of corporate social responsibility. The Enron scandal, for example, was a case study of an accounting firm’s ethics gone sour. The enforced rescue of American banks by the Federal government in October of 2008 revealed the second round of damage to depositor assets caused by ill-considered speculation in mortgage-backed securities. That the underlying assets for these securities were sub-prime mortgages seemed less important than the potential profits; greed mesmerized even investors in the UK and Europe. As a result, the ‘Great Recession’ spilled over across the Atlantic.

‘Sustainable competition’ is the current buzzword for being ‘green’ and minimizing the ‘carbon footprint’ of a business. This goes beyond objecting, say, to the continued operations of E’ON’s coal-fired Kingsnorth power plant in Rochester or to taking grim satisfaction in the closure of the similarly-fuelled Drakelow in Staffordshire. No less an authoritative world body than the United Nations has long urged businessmen to adhere to the ‘triple bottom line’ of ‘Planet, People, Profits’ Töpfer, 2000). The clamour to take control of greenhouse gas emissions aside, Secretary General Kofi Annan (at the time) asserted how business enterprises can work towards environmental protection by: a) shifting to energy- and materials-efficient operations; and, b) providing more employment opportunities in developing nations, where extreme poverty underlies much of the thoughtless environmental degradation that currently takes place. So corporate profits and wealth creation can be honourably compatible with environmental consciousness.

The Special Case of Retail Establishments

For a high street retailer like Marks and Spencer, brand image is a function not only of the quality of goods sold but the totality of service rendered. Every point of contact between the chain and its shoppers matters. This extends from store location (high street versus squalid and deteriorating side of town), how appealing the exteriors and store layout are, the breadth of goods offered for sale, the responsiveness of salesclerks, warranty and returns policies and how these are practised, and the image drivers seen in advertising, promotions, and in-store merchandising (Lippincott Mercer, 2004). All these explain shopper satisfaction, customer experience, and ultimately, brand image.

The Leeds-based Marks and Spencer (M & S) is the 43rd largest retailer in the world, dominant in the UK with more than 600 locations and no less than 295 branches internationally. The chain has been in operation for all of 116 years now, having opened its first shop in Cheetham Hill Road, Manchester in 1894. For most of the last century, M & S established its reputation based on carrying exclusively British-made clothing and premium food lines, though the chain began making room for exports in 2002. For a long time, M & S also followed a consumer-friendly policy of unlimited returns, no questions asked, and only recently began applying a 90-day limit. The current product line has expanded to shoes, cosmetics, scents, home furnishing, luggage, appliances, consumer electronics, and toys.

Profits peaked at over £1 billion in fiscal 1997-98. In the next four years, M & S endured a slump that saw net income fall to one-seventh the record attained in 1998. The problems, some of which continue to this day, included: poaching by competitors who embraced imports from low-cost countries like India and China, the long-time refusal to honour only the store credit card, losing exclusivity in the premium prepared foods niche, refusing to listen to shoppers who perceived food prices at M & S as too high (or not enough value for the price tag), an ageing customer base, clothing lines that lack appeal to the fashionable younger set or to young couples, a brand look that had become tired and stodgy again after a brief flirtation with high-profile supermodel endorsers, a great sprawl of 110 warehouses around the nation that needed streamlining to just four ‘super-depots’, and less than 10% of the M & S customer base taking advantage of online sales with free delivery (Telegraph.co.uk, 2008; Wood & Finch, 2009).

In respect of the aforementioned environmental orientation, retailers usually respond with recycled or biodegradable packaging in place of the ubiquitous plastic bag. There are also those who publicly support suppliers that have modified their goods to become more environment-friendly.

Objectives

Research Problem/Aim

With Marc Bolland just taking over at the helm of M & S, it is timely for the chain to reassess its brand image and find out how shopper loyalty and profits might be re-energised once more. These straightforward marketing objectives require addressing such fundamental marketing research problems as:

- How does one optimise the M&S brand proposition?

- Where is there scope for recovering competitive standing?

- How do present and potential shoppers regard current advertising campaigns and alternatives the ad agency might formulate?

- Where are the most immediate opportunities for repositioning M & S?

- What is the optimal pricing strategy for the many clothing lines and for recapturing leadership in the premium prepared food category?

- How does one create chain loyalty among the next generation of shoppers?

Amongst many key issues, the research question bearing on how to appeal better to younger shoppers is strategically most vital. Granting that the over 55’s have more disposable income than any other population cohort, losing the 35-to-50 market bodes no good for the long-term sustainability of the chain.

Like other high street and shopping plaza retailers, M&S have diversified enough over the years to be able to target different market segments with well-thought-out brand lines. If this research can reveal the expected insights, the chain directors can then re-energize such youth-targeted clothing lines as Autograph, Limited Collection and Per Una.

Research Objectives

- How can M&S appeal more strongly to a younger cohort of shoppers?

- What are the opportunities for weakening loyalty to competing chains?

Research Questions

- Why do younger shoppers prefer competing chains?

- What existing product lines of M&S are most attractive to younger shoppers who currently patronise other chains more often?

Hypotheses

- Casual chic, like prints and mini-dresses, exerts a stronger appeal with young shoppers.

- Celebrities in sports and pop music will make M & S more exciting again for younger shoppers.

Methodology

Research Approach and Design

We propose to do primary research, employing a quantitative survey of the shopper intercept type.

Population of Interest and Sampling Design

The universe is defined as all shoppers 35 years and up. The sampling design is purposive in nature since it will focus on those leaving M & S and BHS branches in a particular metropolitan area. By soliciting interviews with those who have made a purchase, one avoids any selection bias owing to claimed shopping behaviour.

Quota sampling will be employed to equalise coverage by gender, age cohort, hour and day of the week.

Given the multiple segments to be covered, one proposes a total sample of 500 respondents. At a confidence level of α = 0.95 and P = 0.50, such a sample size should yield a ±6% margin of error.

Study Instrument

The study instrument will be a structured questionnaire combining categorical/nominal and rating scales. The questionnaire will be formulated so as to be self-administering.

Aside from the socio-demographic data to be collected for segmentation analysis, the body of the questionnaire will consist of:

Time Scale

Budget

Data Analysis

The Top-of-Mind Brands (Across All Categories) by Reputation

In answer to the question, ‘Considering the brands or names of products and services you know, which three brands do you consider the best?’, M & S ranked third right behind consumer electronics leader SONY and fast-moving consumer goods giant Heinz. Worth noting is that Marks & Spencer enjoys more prestige than the two other retailers that rank highly with consumers: domestic and international hypermarket chain leader Tesco and drug chain Boots.

Table 1

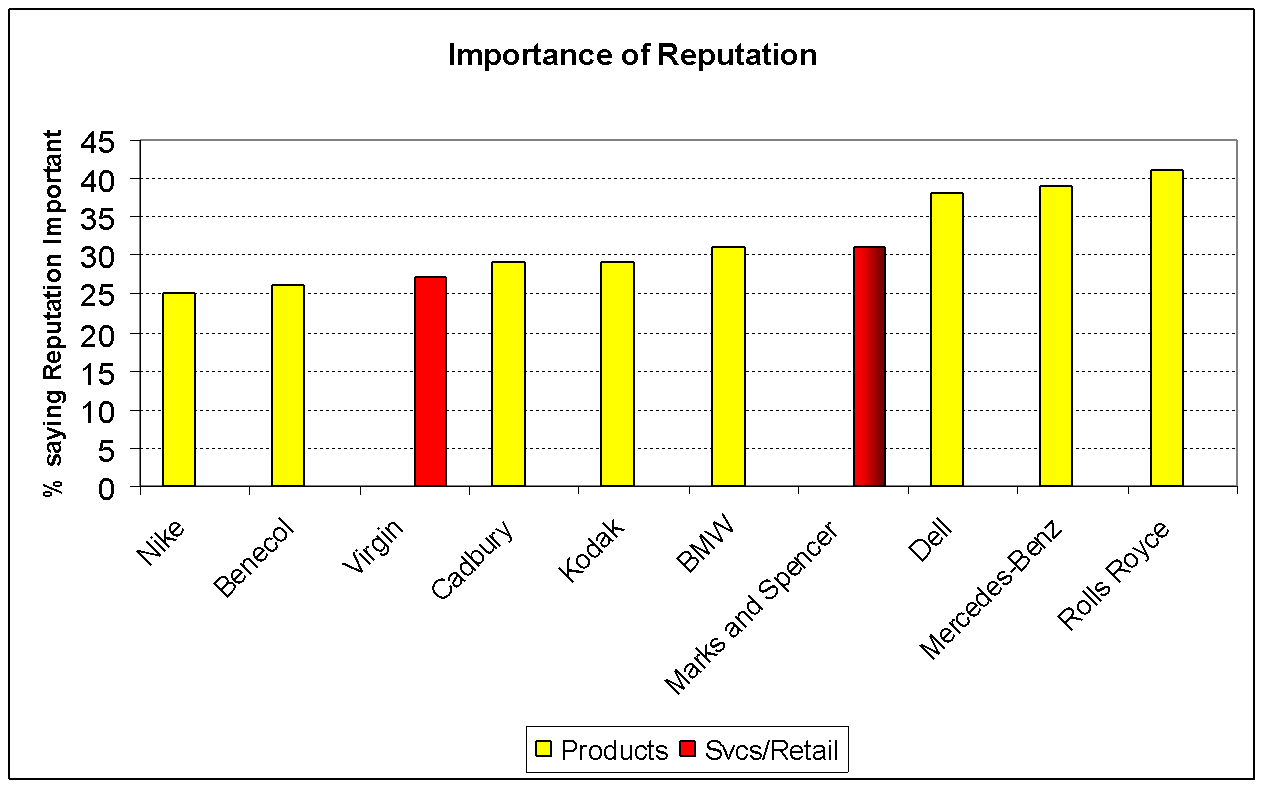

When queried about the importance of corporate reputation to the standing of those companies they regarded as topping their respective fields, shoppers rated M&S’s reputation as among the four most important. That is, admiration for the reputation of Marks and Spencer stood right behind the country’s own Rolls-Royce, those hallmarks of German engineering Mercedes-Benz and Dell, and the well-regarded PC direct marketer Dell.

On this basis, the M & S reputation seemed to stand better than Kodak, Cadbury, Virgin, Benecol and Nike.

Standing versus Other Retailers

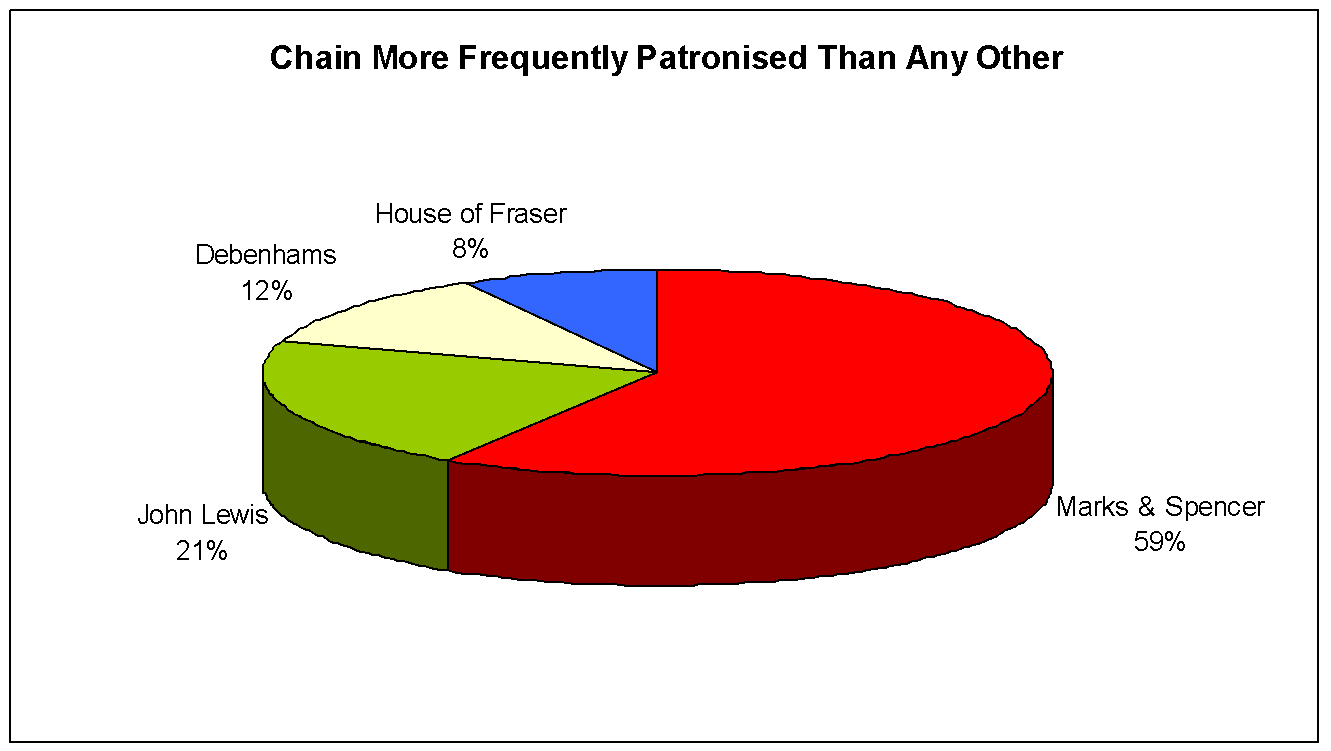

Preference for Marks and Spencer was superlative compared to the next most popular retail chains: John Lewis, Debenhams and House of Fraser. The main reason given was that shoppers could more readily find the right brand of clothing and accessories for their pocketbooks. At the same time, the upper and upper-middle classes liked the convenience of the ‘Simply Food’ store chain that is strongly associated with the parent company.

The Confidence of “No Questions Asked” Returns

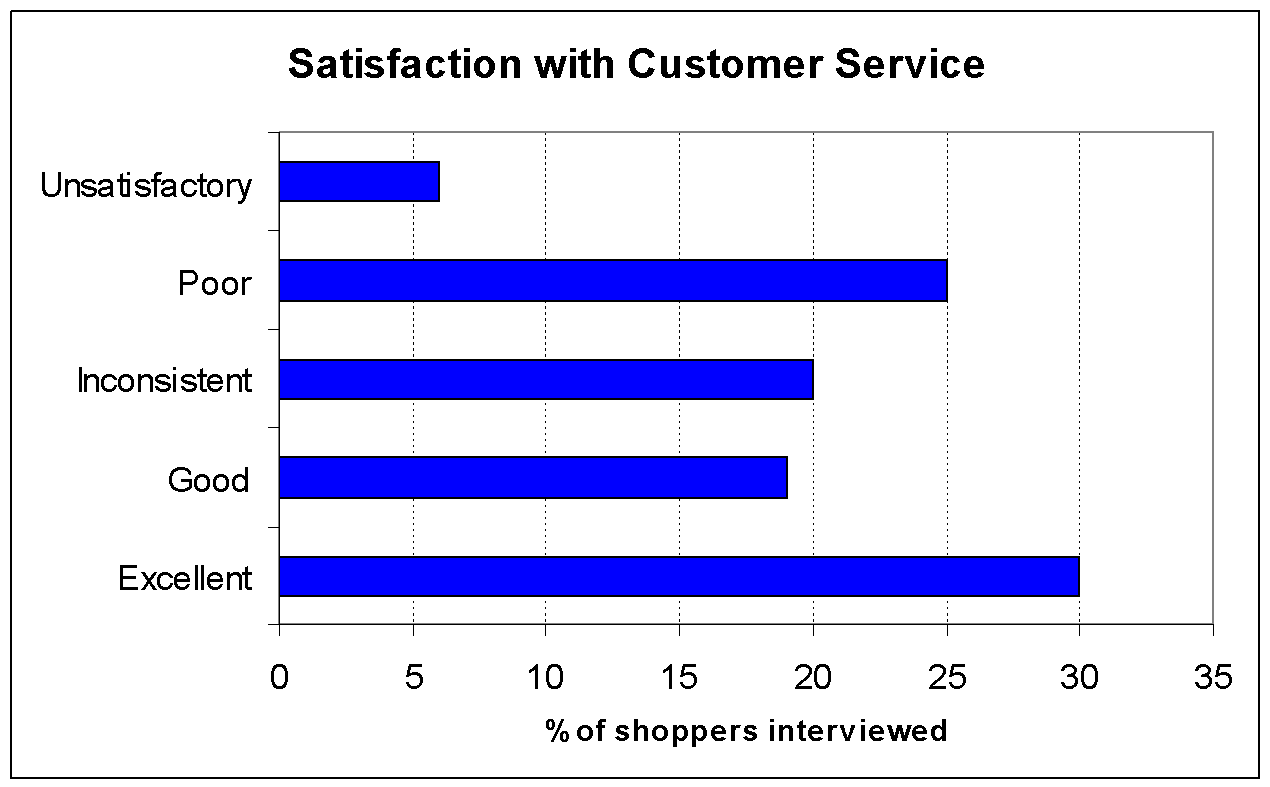

While one concedes that shoppers are, more often than not, completely satisfied with the level of customer service they receive at retail, the present findings nonetheless indicate substantial satisfaction gaps. For one, more than two-thirds are less than fully satisfied and nearly one-third received what they regarded as ‘unsatisfactory’ or ‘poor’ customer service.

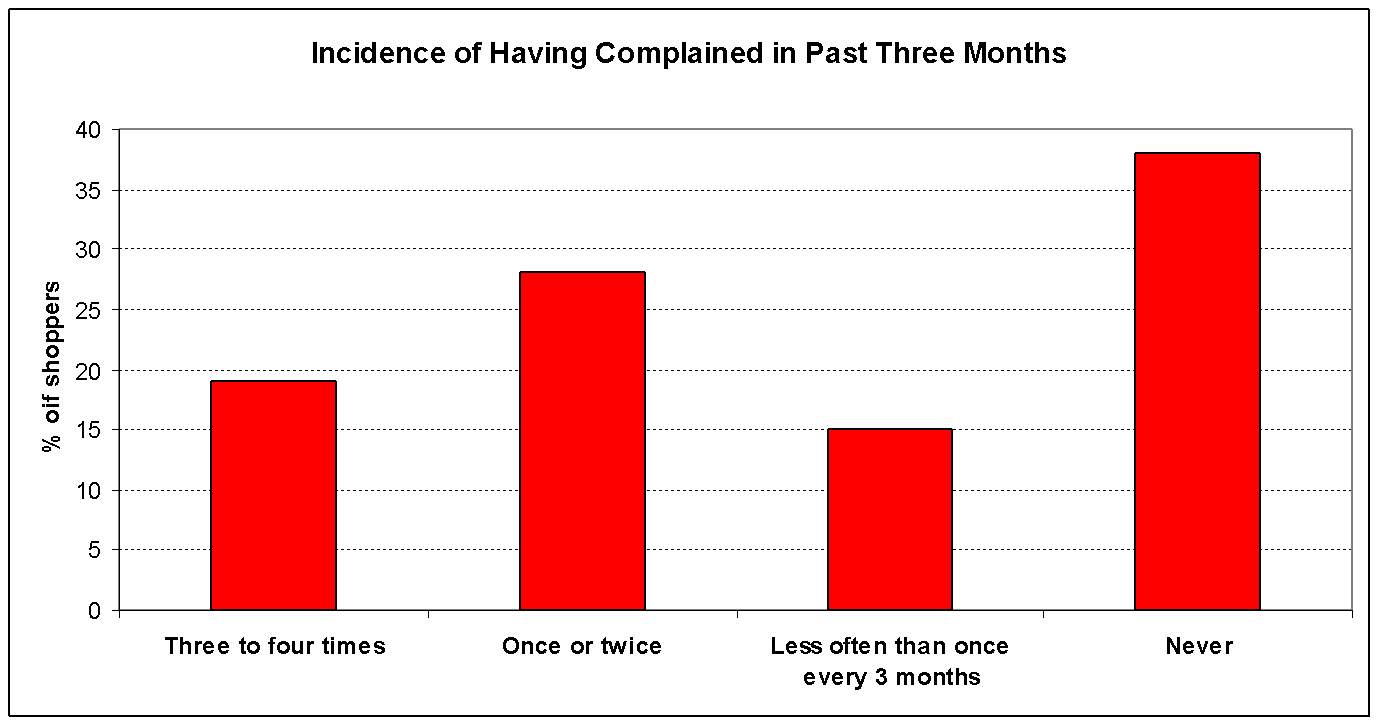

Just over one-third, nearly all Marks and Spencer shoppers had never had to complain recently about disappointing customer service. This held true in respect of both assistance at making purchases and exchanging an item (post-sale service in other industries).

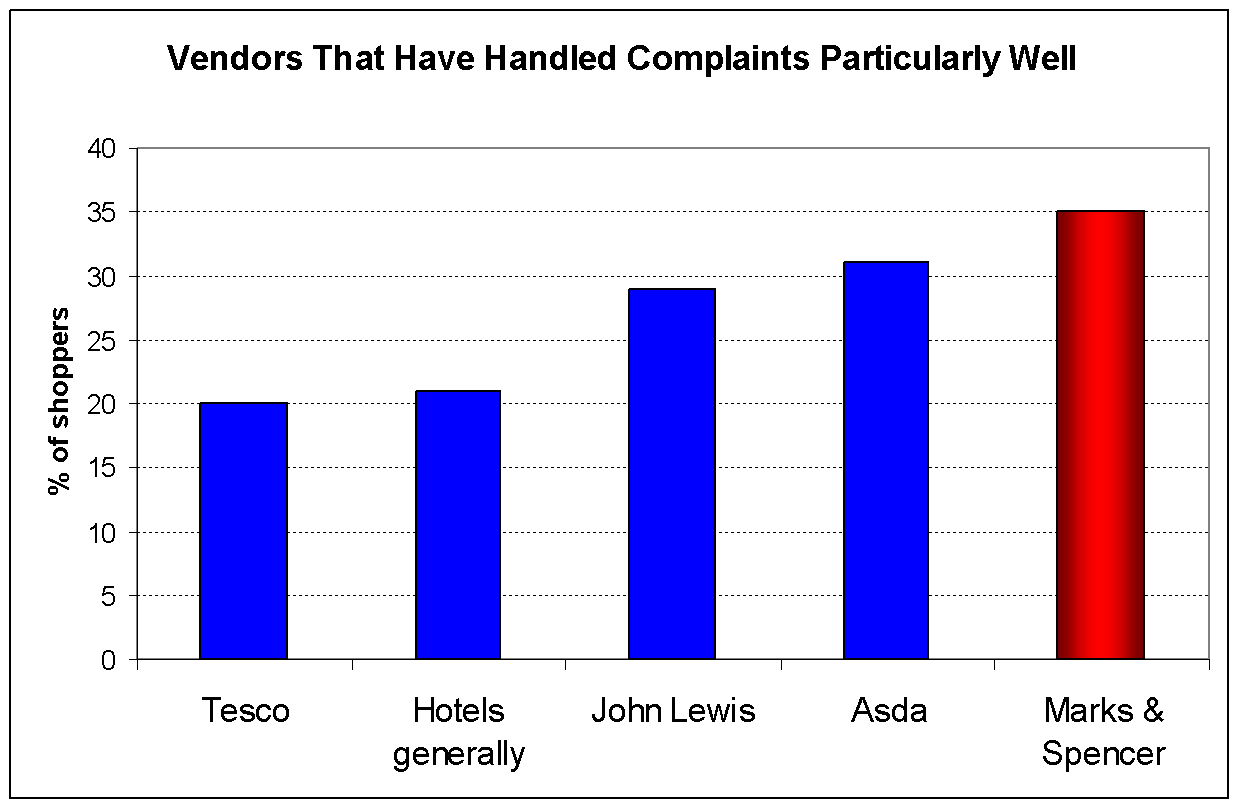

Among the department store and supermarket chains that shoppers spontaneously mentioned as paragons of excellent complaints handling, M & S proved outstanding. This is due, in large part, to what had been until very recently an open-ended exchange policy: as long as the transaction was supported by a receipt, Marks & Spencer accepted any item back, no matter how long ago it had been purchased.

Shopper Priorities

The findings suggest that M & S shoppers may not be significantly more affluent – the amount they claim to spend each month is less than 10% higher than for other department stores mentioned by study participants – but they are certainly willing to pay more for quality and convenience.

Table 2

Table 3

Things Liked at M & S

Despite the great effort made by the chain to enlarge its franchise in wine, ready-to-cook or –serve convenience foods, cakes, desserts and health foods, the high street shoppers who participated in this survey by and large tended to value M & S for wide variety and innovation in garments (see Table 4 overleaf)

Table 4

There is a great deal of emphasis on being fashionably casual. As well, young shoppers in their twenties and thirties seemed favourably impressed not only by the fact that M & S offered many youth-oriented fashion lines now but also by the observation, based on many verbatim statements the researcher received, that the chain could display the latest of the season’s fashions barely three weeks after designers had exhibited them at shows.

Findings

Benefiting from over a century of domestic presence, a category-leading network of stores in the UK and nearly three hundred stores internationally, Marks & Spencer clearly has the advantage of strong brand image and an identifiable core set of brand associations.

That strength of brand image is most evident in the finding that M & S stands head and shoulders with world-class advertisers like SONY, Heinz, Kellog’s, and Coca-Cola and ahead of retailers like Tesco and Boots, at least where mindshare among high street shoppers is concerned. In addition, M & S enjoys better brand recall than John Lewis, Debenhams and House of Fraser. The subsequent findings suggest that high standing rests on a prudently-managed reputation and on having been identified, for the most part, with a core competence in fashion and style.

Reputation as brand image and favourable brand associations is strategic and it has to have been strategically conceived and managed. Among the category-leading matters that have been associated with the brand as part of a deliberate effort is merchandise scope. Others uncovered in this concededly brief study are: ethical behaviour, offering unmatched warranty and exchange service, and shaping the entire corporate culture around the environmental consciousness element of corporate social responsibility.

For most of the last century, Marks and Spencer had evolved into a prestigious retailer of upmarket lingerie and women’s apparel. But as the chain expanded into virtually every town in the UK, alongside Boots and Tesco, this exclusivist positioning could not be maintained. If at first, the history of the chain shows, M & S attempted to be all things to all men and women, such a dilution of brand image quickly became untenable. Today, as survey participants inform us, M & S has bounced back by segmenting the entire product range and offering distinctive brand lines. Thus, there is ‘Rainstorm’ for the nation’s famously rainy climate, ‘Smart-casual’ to give core middle-aged shoppers dress-down weekend chic, ‘Limited Collection’ strongly positioned against the younger set, figure-contouring ‘Magic Wear’ for the flab-conscious women of a certain age, ‘Blue Harbor’ for the men to maintain their own identity, and so on. All these under the umbrella of a strong corporate brand image imbued first of all with a superb-quality association.

Service is not just a matter of enunciating a policy, after all, but also training frontline staff to display a sincere, customer-oriented attitude and empowering them to do the right thing by that policy. This is conceivably the most ethical a retailer can be because it stands behind the quality of all items sold. In the era post-Enron and post-subprime mortgage fiasco, at the same time, the man on the (high) street is more keen than ever that business enterprises wishing to take his money and savings should be as ethical as possible. So even though it may cause M & S some losses in stock that cannot even be put in the ‘best bargains’ bin, there is no question that the liberal policy of returns reinforces the association of the brand with satisfactory quality.

A further, doubtless costly, manifestation of ethical behaviour is the announced goal of going ‘zero-waste’ by 2012. This means M & S commits itself to totally ‘green’ operations, to totally recyclable packaging and educating suppliers to be just as environmentally conscientious when packing goods for delivery to Marks and Spencer depots. Then we see why shoppers put such great store by the reputation of the chain, no matter that it must cost a pretty penny off the price of listed stock.

Bibliography

Dobni, D. & Zinkhan, G. M. (1990) “In search of brand image: A foundation analysis”, in Advances in Consumer Research, Volume 17, eds. Marvin E. Goldberg and Gerald Gorn and Richard W. Pollay, Provo, UT : Association for Consumer Research, pp. 110-119.

Kotler, P. & Keller, K. (2008) Marketing management. 13th ed. New York: Prentice Hall.

Lippincott Mercer (2004) Employees and image: bringing brand image to life. [Internet], BNet Business Library, White Papers. Web.

Pearce, A. & Purser, J. L. (2010) Toyota: fall from grace or bump in road? [Internet], American Marketing Association, Resource Library. Web.

Telegraph.co.uk (2008) Marks & Spencer: A recent history. [Internet] Web.

Töpfer, K. (2000) Weaving the global compact: the triple bottom line. Economic, social, natural capital. United Nations Chronicle, XXXVII (2).

Wood, Z. & Finch, J. (2009) A new face, but the same old problems at Marks & Spencer.