Introduction

From a psychological point of view, the human memory may be said to be the capability on one to store a piece of information and retain or recall it as of when appropriate. The study of this very important phenomenal started with philosophers’ investigation of such possibilities as an artificial enhancement of the memory. Over the years, particularly by the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, there was a lot already done by scholars particularly in the area of cognitive psychology’s paradigm.

Knowledge of memory has developed so rapidly of late so that it is the fundamental pillar of cognitive neurosciences. With the rapid development of cognitive psychology, there are several alternatives to testing of one’s brain. These include testing for audio receptivity or for image receptivity, or for both. This paper is a report of a test of memory for visual receptivity and retentiveness through a conceptual model that was designed to help retain pictured images.

The Concepts of Working Memory, Short-term Memory, and Long-term Memory

For one to articulately understand the concepts of working-memory, short-term-memory, and long-term-memory in present days, he or she has to streamline the three memory types to specifics of what constitutes or makes a difference or similarity in working-memory, short-term-memory, and long-term-memory (Schacter, 1996). This, of course, is because there are numerous confusing arguments regarding the three from different scholars.

From a general point of consideration, however, short-term memory constitutes 2 distinct properties including a demonstration of chunk-capacity limits, and the ability to decay temporarily. There is equally a significant controversy on the differences between these 2 properties (Schacter, 1996).

One’s understanding of the concept of working memory is therefore build around 3 slight discrepancies. These discrepancies, according to Atkinson & Shiffrin include ‘short-term memory applied to cognitive tasks, a multi-component system that holds and manipulates information in short-term memory, and the use of attention to manage short-term memory’ (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968, p. 95).

But even if one fails to consider this Atkinson & Shiffrin’s point of view, he or she will note that there is an expression of short-term memory that appears to be routinely conducted and would by no means show any clear relationship with cognitive measures (including the ones that are known of the expression ‘working memory) which possibly demand a higher level of attention and as well correlate better with the aptitudes.

Distinctively, the possibility of any existent differences between short-term-memory and long-term-memory stores happens to be with duration and with capacity. According to Cowan, ‘a duration difference means that items in short-term storage decay from this sort of storage as a function of time. A capacity difference means that there is a limit in how many items short-term storage can hold’ (Cowan, 1995, p.103).

In cases where there are capacity limitations, few articles which are below limits of the capacity may be left to be stored in short-term pending their replacement by fresh events. But these limits have quite a number of controversies. For one to determine how useful short-term storages are, it is pertinent to consider capacity limits as well as required duration for such storages.

The use of ‘working memory’ has often meant temporary memory as considered in terms of functionality. But this angle at which working memory is looked at does not product a clear line that separates the understanding of what stands between working-memory and short-term-memory. The 2 differ specifically in terms of property demonstrations: chunk-capacity limits and temporal decay. Where there is significant information on the earlier, idea on decay has continued to be notional.

Description of Selected Test and Results

For many years now, several tools and machinery and techniques have been applied in memory tests by different persons at different instances. The Rhyme/number technique, for instance, is used for memorizing a list of things in a specified sequence while effort is made not to forget items as they appeared. The shape/number technique has also been structured in almost the same way as the rhyme/number technique and works similarly.

Several years ago, the Romans used the roman-room mnemonic in recollecting data that was not structured. Over the years these techniques have continued to evolve. In 2004, Memtest developed and used memtest86+ for memory testing. For most memory testing tools, there is an effort to make their usage as simple but effective as possible. Memory testing mechanisms could be designed to incorporate both or either of verbal or word and/or visual or pictorial receptivity and retentiveness by the brain.

In case of our study here, visual receptivity test was conducted through a conceptual model that was designed where 20 pairs of different alphabets were painted with varying colors- a pair had the same color- totaling 40 alphabets altogether. And one out of each pair was picked and dropped in a tray and then the tray was shaken vigorously to enable the alphabets rearrange themselves at random.

These were then observed for a set period of 5 minutes after which the remaining units of the pairs were arranged in a second tray to reflect the placement and color position of the alphabets in the first tray. In a first effort to reproduce exactly the alphabets in tray 1 in tray 2, 10% of the alphabets in the first tray were perfectly positioned in the second tray in corresponding color and alphabets.

The time for observing the position of the alphabets in tray 1 was increased to 10 minutes after the alphabets were vigorously shaken again. During this time, 25% of the corresponding alphabets in tray 2 were arranged both in color and alphabets. The time for the observation was increased to 15 and the 20 minutes, and 60% and 80% corresponding positioning of alphabets in tray 2 were achieved respectively.

This simple but effective memory test indicates that there is usually an improvement with one’s ability to score higher as one keeps on with practice- even though it might not necessarily reflect a general improvement in one’s memorizing ability. A memory test at the first instance of trying must be taken very serious since it best reflects one’s most honest ability.

Explanation of the Role of Encoding and Retrieval in the Memory Process and how They Relate to Selected Test and Results

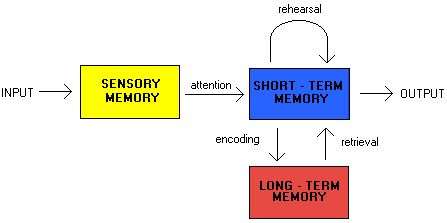

There is an intricate connectivity between encoding and retrieval memory processes. In his studies, Broadbent referred to this as, ‘…the processes of moving information to and from short-term memory (STM) and long-term memory (LTM), respectively (Broadbent, 1975, p.86).

The interconnectivity linking encoding/retrieving processes and memory has been presented in an information-processor form as follows:

Figurative representation of interconnectivity between encoding and retrieving processes and memory

Encoding has to do with connecting fresh information with what has been known previously as an effort to modify the fresh information to a better appreciated one. Broadbent reviewed that, ‘the quality of this process is related to the degree with which new information can be integrated or assimilated with existing knowledge’ (Broadbent, 1958, p. 62). Equally, Baddeley notes that, ‘much encoding involves labeling thoughts with words, but pictorial or other forms may be used as well’ (Baddeley, 1986, p.100).

The fundamental aim of engaging any encoding strategy is based on an attempt of improving the capability with which one transfers short-term-memory information to long-term-memory (Hebb, 1949). Based on the fact that testing has proven to be the simplest tool for evaluating data and information, encoding and retrieving models and tools such as the conceptual model used earlier has the capability of enhancing performances by students in practical tests and exams.

Evaluation of Variables Associated with Encoding Information and Ease of Retrieval as they Relate to Selected Test and Results

The findings form our studies are an indication of the role played by regions in encoding/retrieval of intermittent information ahead of that needed for uncomplicated recognition of items.

Conclusion

The human brain exhibits the capacity of storing information in varying degrees depending on individual’s receptivity, storage, and retrieval potentials. The stored information could be in the form of working-memory, short-term-memory, or long-term-memory. Generally, short-term memory constitutes 2 distinct properties including a demonstration of chunk-capacity limits, and the ability to decay temporarily.

It applies to cognitive tasks, a multi-component system that holds and manipulates information in short-term memory, and the use of attention to manage short-term memory. The possibility of any existent differences between short-term-memory and long-term-memory or even working-memory stores happens to be with duration and with capacity.

This paper deliberates on the subject matter of memory through a visual receptivity test that was conducted using a conceptual model that was designed where 20 pairs of different alphabets were painted with varying colors. The result from the test indicated that there is usually an improvement with one’s ability to score higher as one keeps on with practice- even though this might not necessarily reflect a general improvement in one’s memorizing ability.

Reference List

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: a proposed system and its control processes. In: Spence KW, Spence JT, editors. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory. New York: Academic Press.

Baddeley, A. D. (1986). Oxford Psychology Series No. 11. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Broadbent, D. E. (1958). Perception and Communication. New York: Pergamon Press.

Broadbent, D. E. (1975). The magic number seven after fifteen years. In: Kennedy A, Wilkes A, editors. Studies in Long-Term Memory. Oxford, England: Wiley.

Cowan, N. (1995). Oxford Psychology Series No. 26. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hebb, D. O. (1949). Organization of Behavior. New York: Wiley.

Schacter, D. L. (1996). Searching for Memory: The Brain, the Mind, and the Past. NY: BasicBooks.